The Best Venture Firm You’ve Never Heard Of

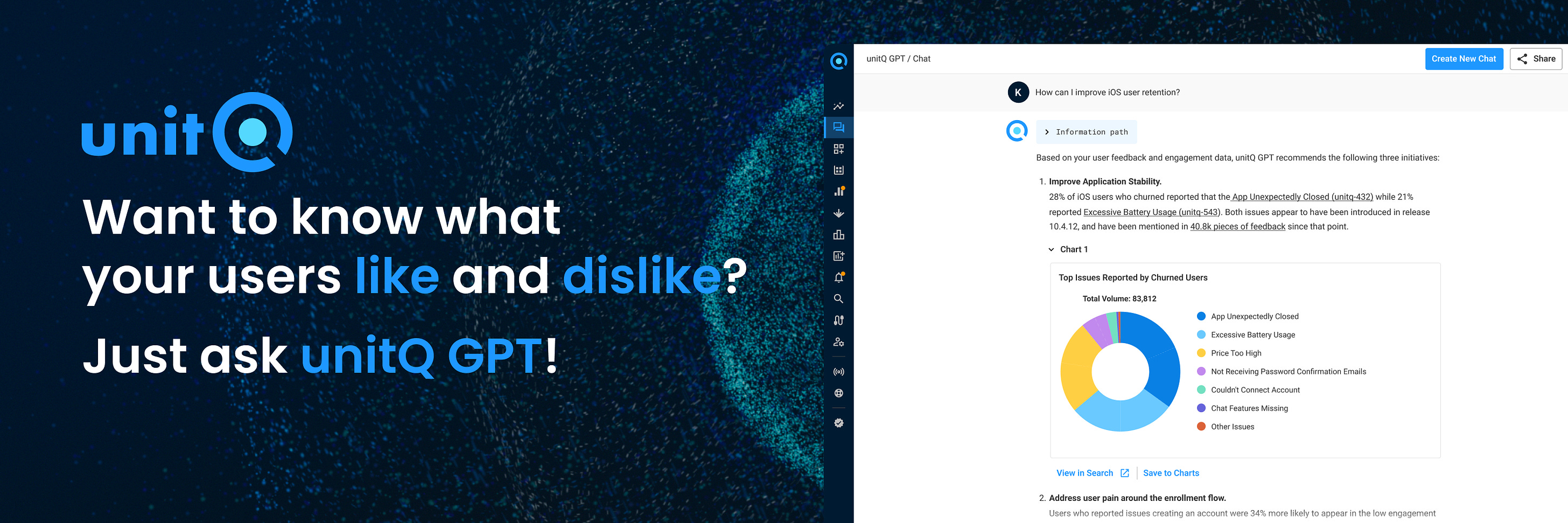

The Best Venture Firm You’ve Never Heard OfHummingbird Ventures has built an astonishing track record – all while staying out of the limelight. Its secret to success? A meticulous approach to identifying outlier founders.Friends, Sometime in 2021, a friend sent me a DM. “Ever heard of Hummingbird Ventures?” I hadn’t. I responded as much to my friend. He wrote back: “You won’t believe their returns.” Interesting, I thought. Then, I promptly forgot and went about my life. Thankfully, I was reminded of this conversation several times over the past year or so. I heard someone else make similar remarks about Hummingbird’s exceptional returns, re-piquing my interest. I saw their name begin to show up on cap tables of companies I found intriguing. And finally, I was introduced to their team, witnessing their meticulous, rather peculiar way of thinking. So, this summer, I decided to get to the bottom of it. Were Hummingbird’s returns really as good as my sources had said? How had they done it? Why were they so under-the-radar? For the past four and a half months, I have been obsessed with these questions and several more philosophical ones, such as: Is progress always messy? Do we have to like someone as a human to invest in them as a CEO? How much of venture capital is about investing in the world you want to see versus investing in the world as it is? To get the answers, I’ve interviewed nearly twenty sources, accessed and reviewed a heft of internal documentation, studied the past, spent a lot of time hearing from Hummingbird’s spotlight-shy investment team, and intermittently lost my sanity. The result is, I think, the most interesting story I have written this year. (It is certainly the most detailed.) If you’re interested in the messiness of entrepreneurship, dramatic founding stories, unorthodox approaches to investing excellence, and discovering what makes a great founder, keep reading. A small ask: If you liked this piece, I’d be grateful if you’d consider tapping the ❤️ above! It helps us understand which pieces you like best and supports our growth. Thank you! Brought to you by unitQIntroducing unitQ GPT: The world’s first generative AI engine for measuring the quality of your products, services and experiences. unitQ GPT revolutionizes how product builders, engineers, and support leaders understand user feedback in real time to build superior products, fix bugs faster and resolve support issues at scale. Just ask a question and get an answer based on granularly categorized, AI-driven user insights.

Just ask!

Actionable insightsIf you only have a few minutes to spare, here’s what investors, operators, and founders should know about Hummingbird Ventures.

The bumblebees were kept in the freezer. When the boy searched for ice cream, he would find them. It wasn’t easy to tell what they were at first: their bodies piled on top of one another, paper wings stiffened, and half-yellow coats furred by the cold. He was old enough to understand why they made no more sound but not why his grandfather had put them there to begin with. What motivated a person to close a bag of bumblebees to the euthanizing cold of a freezer? What did his grandfather hope to achieve? It was Barend Van Den Brande’s first confrontation with how strangely, how discomfitingly intellect could manifest. He would come to make a career out of such encounters. In 2010, Van den Brande founded Hummingbird Ventures, registering the investment firm in his native Belgium. He did so with little fanfare and absent of interest from Silicon Valley’s brand name firms. Anyone bored enough to note Hummingbird’s establishment would hardly have given it more than a moment’s thought: an unheralded manager had started a small venture capital firm in a small country. Belgium, then as today, was best known for its blonde ales and wafels, not its vibrant tech sector. From his home base in Antwerp, however, Van den Brande set about building his venture firm. He did so without many conventional advantages. He did not have a proven track record, nor had he apprenticed at a storied fund. Though he had worked as a financial analyst in Boston for a spell, he had few connections to the power brokers of Sand Hill Road, let alone the endowment managers sitting beyond the green-felt lawns and pale stone of the Ivy League. And, as he would have told you himself, he was a bit odd. Van den Brande lacked the easy charm that could beguile entrepreneurs into parting with their equity or seduce limited partners into penning a check. What he did have was formidable intelligence, jolting directness, ferocious curiosity, and a total allergy to bullshit. These final two traits would prove the making of Van den Brande and his firm. In the thirteen years since its founding, Van den Brande has built Hummingbird into one of the best-performing venture funds of the past decade. It has delivered three vintages with over 10x net returns. It’s done so without hitting the buzziest startups of the past cycle, instead capitalizing on a roster of relatively under-the-radar giants, including Peak Games, Gram Games, Kraken, BillionToOne, and FPL Technologies. It’s the kind of sustained excellence liable to make marquee fund managers up the dosage of their daily nootropics out of concern. Hummingbird has achieved this success while staying out of the limelight. True, it has built a strong reputation in Europe. But ask the average tech founder for the continent’s power players, and Index, Accel, Atomico, Balderton, and Northzone are more likely to be mentioned. Make the same query about the United States, and the names of several other avians, mammals, trees, and fruits would be mentioned before anyone turned to the humble Hummingbird. Though known by their entrepreneurs and listed on the occasional cap table, they are virtually anonymous to even sophisticated American audiences. Van den Brande and his team have driven such returns by ignoring much of the asset class’s conventional wisdom – and forging an extremely opinionated investing framework. Many venture capitalists emphasize the importance of the entrepreneur to their underwriting; none mean it quite as much as Hummingbird. For Van den Brande’s firm, the founder is not merely important; they are the only thing that matters. Forget about flocking to a hot new market or playing nice with Sequoia or Benchmark. If you want to deliver consistently superior returns, Hummingbird believes you need to find the most exceptional entrepreneurs on earth – not merely the top 1%, but the top 0.1%. Finding such outliers is not easy. It also might not look like you’d expect it to. Hummingbird isn’t searching for the slick Stanford MBA, affable Google APM, or winsome McKinsey associate. It cares little for credentials or the experienced pitchman’s smooth patter. Instead, Van den Brande’s seven-strong roster of investors is pursuing a very specific kind of entrepreneur – someone with unreasonable ambitions, astonishing clock speed, and a frightening hunger that portends a deep, personal unease. Such people do not always make adept students or easy colleagues. But they’re liable to have a handful of bumblebees buried in the freezer. And to have a good reason for it, too, if you care enough to ask. Hummingbird’s chief virtue is its ability to ask questions that give these anomalous founders the comfort to open their metaphorical ice boxes and reveal the strange, raw edges of their personality inside. To understand how this firm works, we have spent more than four months researching Hummingbird, investigating its returns, and speaking with nearly twenty sources, including its founders, team members, entrepreneurs, external parties, and other fund managers. Many shared their stories on record for the first time. The investorThroughout his career as a venture capitalist, Barend Van den Brande has likely heard upward of 10,000 pitches. Ten thousand times, a founder has sat before him and told a story. They have spoken of their background. They have narrated the problem before them. And they have unfurled their solution. It is the job of a venture capitalist to listen to such stories – and to poke at them. To find the holes yet to be darned and stick a finger through the fabric. To find the story beneath the one being told, hiding. To hear what is being said and what is not. Van den Brande appears to have honed this skill much more finely than the average practitioner. “The thing that has struck me the most, that is unique about Barend, is that he has this linguistic mind,” Salar al Khafaji remarked. “He’s very, very language-oriented. The only other person I’ve met that has the same [propensity] is Mike Moritz.” Hummingbird invested in al Khafaji’s autonomous building platform, Terraform, in 2021. Perhaps because of this skill, Van den Brande is a halting narrator of his own story. He worries that the details he includes – and those he elides – set a path for the listener, the reader, to follow that, by necessity, deviates from reality. A story can never encapsulate the fullness of someone’s life, no matter how diligently it is told or transcribed. There will always be a sly cut, a subtle jump, an omission, a conflation. Speaking with Van den Brande, you get the sense he would prefer to download the entirety of his life experiences and hand it over on a USB to avoid any confusion. “I’m very worried about narratives,” he said in our conversation. “I’ll share with you a number of narratives; I just worry that they are narratives. And before you know it, if you have enough of these narratives, you become a cartoon, you become a cliché.” Van den Brande’s disclaimer reveals something of his mind, his selfhood, and the stories we will tell about his life. He seems to be saying: Listen to my stories, take them for what they’re worth, but don’t imagine they explain everything. The city of Mechelen is nearly equidistant between Antwerp and Brussels. It occupies Belgium’s Flemish region, a country that Van den Brande describes as a “compromise.” After generations of French, German, and Dutch sallying back and forth over the same stretch of land, an independent country formed. “Apart from surreal artists and a couple of artful soccer players, it’s not necessarily a country known for success in technology or for conquering the world.” It was here that Barend Van den Brande was born. Belgium’s Flemish identity was an important aspect of Van den Brande’s upbringing. His father, Luc Van den Brande, was Mechelen’s representative in Belgium’s House of Representatives before becoming Minister-President of Flanders; his mother was a teacher and homemaker. When Van den Brande reflects on his childhood, he skips over much of it. But he makes time for the bumblebees. Yes, those bumblebees. While Belgium often felt “provincial” to the young Barend, an environment where people cared too much about what others thought of them and innovated too little, his grandfather was an exception. “[He was] this crazy inventor grandad,” Van den Brande recalled. “The type of person where – normally, you would go to the fridge of your grandparents and maybe take out an ice cream, right? When I would go, I would still find ice cream. But what I would [also] find was a bunch of frozen bumblebees.” What was he doing with them? “He was experimenting with combining different species of them and trying to find a very healthy one.” In particular, Van den Brande’s grandfather was obsessed with how bumblebees might improve tomato production. To stimulate pollination in greenhouse environments, humans typically walked from one tomato plant to another, holding what it is tempting to call a vibrator. This vibrating device emitted a frequency that emulated a bumblebee’s buzzing, shaking pollen from a tomato plant’s flowers. Though reasonably effective, it was a slow, manual process. Couldn’t bumblebees manage the task themselves? Particularly if engineered for it? Van den Brande’s grandfather would never commercialize the biotechnology he developed, though a few years later, another Belgian tinkerer did. In 1987, veterinarian Roland De Jonghe started a company named Biobest, offering genetically engineered bumblebees to aid with tomato plant production. It has gone on to produce hundreds of millions of euros in revenue, demonstrating the potential of even erratic-seeming experiments. The wacky grandfather is one of the “narratives” Van den Brande cautiously offers about his early years. The other came nearly a decade later and carried none of the same charm. On a family vacation bordering the North Sea, Van den Brande suffered a windsurfing accident that almost drowned him. Hours later, he was lucky to float ashore at De Panne, a town near the French border. Reflexively, he underplays the experience – “You [can] connect the wrong dots, right?” – but it’s clear it marked him. In the immediate aftermath, he recalled reckoning with his mortality. “I suddenly felt like, ‘Poof! Life can be really short. Let’s do something with it.’” Even years later, he would find himself returning to the incident and the subject of near-death experiences. “We live as if nature and nurture were equal parents when the evidence suggests that nature has both the whip hand and the whip,” the author Julian Barnes once wrote. While Van den Brande’s upbringing influenced who he became, a particular personhood is baked into the genes. From an early age, Van den Brande was distinctly different from those around him, a discrepancy he would come to categorize in later life as “a level of masked autism.” At the University of Louvain, he preferred the company of engineers to the economists in his program. Though he received a Master’s in that subject, he spent much of his time studying philosophy. Spend enough time with Van den Brande and this interest becomes clear. Few other investment managers’ internal writing begins with a convincing discussion of Cartesian dualism. Architecture was another interest that germinated during this period. If you were to meet Van den Brande without context, this is the career you’d pick for him based on sight alone. His precise features, round, dark-rimmed glasses, keen gaze, shock of blonde hair, and vaguely Nordic bearing suggest a life designing trendy bungalows in Oslo. As it happens, Van den Brande has built a house – several, in fact. During his years as an investor, architecture acted as a release from the limitations of investing. “VC has this weird tension. Everything in a startup needs to happen now. But at the same time, as a VC, you put a pawn on the chessboard. For a while you have this idea of ‘Wow, what if we can help [our entrepreneurs]! Let’s interview another twenty VP Sales candidates and do all these things!’ In reality, what you need to accept at some point is that, yeah, maybe they’ll take a little bit of your advice, mostly not. The good ones won’t.” And so, into the early hours of the morning, Van den Brande turned to architecture as a creative outlet. “I always felt it kept me sane,” he said. His crowning achievement is a property in the Alps, up at 2,200 meters. “You get there with a ski-doo. It’s really tough building conditions.” Both philosophy and architecture seem to say something about Van den Brande. He is abstract and exacting, cerebral and results-oriented. It took a few years after graduation for Van den Brande to make his way into venture capital. It wasn’t a typical career in Belgium in the early 1990s, meaning that it didn’t show up on his radar as an option for several years. He worked as a financial analyst at SG Cowen’s Boston office, studying nascent internet businesses. By 2000, he was ready to begin investing in this class of companies himself – but not before considering writing a book. His experience off the coast of Belgium had stayed with him in the intervening years and made him wonder how many others had experienced similar hazards, both personal and professional. How had it changed them? What residue had it left on their selves, their souls, their lives? In particular, he was interested in how many entrepreneurs had undergone something that affirmed their fragility, their mortality. He hoped to convince founders to share such experiences, creating a kind of compilation of hardship. The book did not get very far. “I got to reach out to a number of European entrepreneurs around the year 2000. [This was] the first generation that had built something, probably to the tune of $50 to $100 million outcomes. So I called them up, and I said, ‘Hey, I need you to talk openly about that.’” He was swiftly met with two types of dismissals. “One was typically combined with a condescending ‘my friend’ or something – which would be like, ‘Listen, my friend, I’m not going to be a chapter in the book; I’m going to be a book.’” The ego of these participants prohibited them from participating in a project with such a diffuse focus. The second type of rejection was more interesting to Van den Brande. “The other ones said, ‘Listen, you’re onto something. But if people were to know how at some point I was crawling on the ground at a junction and all the way thinking I was going to go left and then in the very last moment [taking] a right – in my next crisis, I don’t think I want half of my team [to know] exactly how it went in my darkest moments. They need to trust me as a leader.’” Though Van den Brande’s book project didn’t go anywhere, that second type of response solidified his intuitive sense that he was onto something. That the task of building a company from nothing was darker, rawer than many made it seem. “I think we’ve always been on the lookout for: ‘What is the Pixar version of a startup? What do we want to believe about the world? What should be a good world – with all of us [having] equal chances of being a founder?’ And then, waking up to: ‘Oh my god, this power law thing is real. This is scary. Like, you can win for a while in Europe, and then a Brazilian 17-year-old might literally eat you up in two years. So you better find a solution.’” It would take a long, difficult decade for Van den Brande to truly commit to the ideas he was circling. The educationThe same year he tried and failed to compile his book of trauma, Van den Brande officially began his career as a venture investor. In 2000, he took the wraps off Big Bang Ventures, a €10 million fund focused on the Belgian startup ecosystem. Though Van den Brande was several years out of university by this point, his newest endeavor would provide a humbling education of its own. Van den Brande founded the firm with a fellow Flemish graduate, Frank Maene. After receiving a pair of Master’s degrees in economics and accounting, Maene had spent a stint in America, working with the growing cadre of dotcom companies. “He had been in a startup before in the States. The only Belgian guy in a startup and in sales [over there].” That expertise felt invaluable to Van den Brande at the time. “I was like, ‘Oh, wow! Someone that has seen the inside of a startup. Let’s start this together.” To further bolster Big Bang’s bonafides, Van den Brande recruited a roster of entrepreneurs to serve as advisors. The fund’s approach was simple and logical. “My thesis was that: ‘Oh, look, in Europe we’ve got a bunch of wonderful old universities.’ This is how naive it was. My best take was, ‘Maybe we’ll find smart people very close to universities. And probably Belgium has been overlooked.” Though a reasonable premise, Van den Brande would quickly find its limitations. First among them was that Belgium was too small a market. “Way too tiny,” Van den Brande remarked. He expanded his scope to the Netherlands. Then France, then Germany. So began the “macho phase” of Van den Brande’s VC career. He packed his day with coffee meetings, business lunches, and networking events. He was burning with energy to do something, and, absent of a better idea, he chased the opportunities that came his way and scurried for the companies he backed with frenzied intensity. In part, this convivial whirlwind soothed Van den Brande’s desire to placate his limited partners (LPs). He explained his tendency during this period to jump into the fray with Big Bang’s founders, saying, “I wanted to go to my LPs and be like, ‘Look, look, look, we’re almost company builders.’” The other reason Van den Brande spent his time this way was that it was alluringly, deceptively pleasant. “The thing is, as a VC, you can feel really, really good about your life. Why? Because you talk to seven, eight, ten wonderful entrepreneurs – people full of energy, amazing ideas, and in a domain where you’re scratching the surface. And so, you can be at the end of any given day feeling like: ‘Woof, this was a rich, wonderful day.’ It’s possible that you have not created any value, you’ve not done anything useful.” Some venture investors may spend their lives this way. If you are not careful, decades can pass in the thin glow of dazzling company. A career can be made not so much by thinking or doing but by appearing to think or do. Though some part of Van den Brande enjoyed the shallow satisfactions of performing the role of venture investor, it never felt a perfect fit. Even during his greenest years, there seemed to be a niggle, an itch, a prickling dissatisfaction that stopped him from embracing the role entirely. For one thing, Van den Brande invested slowly. In 2000, Big Bang’s inaugural year, the fund backed a single startup. While a cautious pace at the best of times, it was especially so during the febrile rush of the dotcom era. “People were just frantically doing deals. Probably even shareholders [thought]: ‘Yeah, just pick up a couple of these companies. Anything seems to go public. And then we’ll plug in a little bit more pre-IPO money.’” Even as the bubble began to burst the following year, Big Bang’s LPs didn’t see much value in Van den Brande’s measured deployment. “The same shareholders sat me down and said, ‘Hey, you know what? The Swiss seem to be good at making watches. And we seem to be good at doing things like chocolate. And the Americans, they seem to be good at things like software. But you’ve done like one investment. Maybe this is not your thing. Maybe in Europe, funding amazing tech companies is a bit too much to ask. And why wouldn’t you do something else? Because you’re clearly not very good at this.” Van den Brande’s approach would be vindicated in time. By reserving capital for the years after the dotcom bust, he avoided an early, ignominious end to his investing career. “It was good that I wasn’t just boom, coming to action and wanting to leave a mark and doing ten, twenty investments. That would have been the start and the end of my career.” Indeed, that reserve would subsequently help raise a €31 million follow-on vintage. Still, he understood his LPs’ criticism and felt more than a little dissatisfaction himself. Though he filled his days meeting entrepreneurs, he had yet to meet one that seemed unmistakably unique. As Van den Brande described it, he spent his days walking a vast beach, turning over shells. Over nearly nine years at Big Bang Ventures, he studied thousands of them in search of one true anomaly, one perfectly imperfect shell. By 2009, Van den Brande had invested €41 million without finding a single outlier founder. Big Bang’s performance reflected as much. Though nine portfolio companies were eventually acquired, including by major firms like Sun Microsystems and FIS Global, the fund barely returned LP’s money. “I think they got something like 9% net IRR,” Van den Brande said. That wasn’t bad for vintages at the time, putting Big Bang in the top quartile, as Van den Brande recalled. Still, it didn’t convince Big Bang’s ambitious manager. “If you want to be part of the next Google, there was no sign of that.” Above all, Van den Brande felt that venture capital was almost nothing like he’d expected. Though he had read industry blogs, sought out the counsel of American investors, built an advisory board, devised a rational thesis, and spoken to as many founders as he could, he felt he’d scarcely broached the marrow of investing. He’d done things by the book, but where had that gotten him? “I remember thinking: ‘What I need to do now is more than a 10% change. There’s something entirely off. I need to turn up the volume a little bit and really question everything.’” As the world readied itself for the next decade, Van den Brande made a decision: he would start a new fund with a radically different strategy. In 2010, Hummingbird Ventures was born with €19 million under management. Though Van den Brande didn’t yet have the words for it, this firm would operate with a radically distinct philosophy. Above all, it would relentlessly search for the kind of outlier people Van den Brande had yet to find. It did not take long for Hummingbird’s GP to be rewarded. The same year Barend Van den Brande launched his new firm, he met Sidar Sahin. The meetingThe vast nature reserve of venture capital houses a variety of species. There are the peacocks that flash their feathers and do little else. There are the lemmings, darling tundra hamsters that scrabble and careen in a general direction. There are the lions, great beasts whose roars ensure none in the kingdom miss their prowess. And there are the wolves that may move in packs but do not need one, that howl with saudade but prefer silence, that hunt with little noise but full lethality. Pamir Gelenbe is a wolf. He has invested in exceptional companies, and yet, search his name on Google, and you will find little more than a page of decrepit links and old photos. He last tweeted in 2020. While that is not nothing – he has not disappeared into a cloud of vapor – it represents a fraction of the press, attention, and noise his work might have garnered were he an aggrandizing lion. True to form, Gelenbe declined to be interviewed for this piece. “[Pamir] has a big role in this story,” Van den Brande said. Exactly what role? Gelenbe’s involvement with Hummingbird began in 2010. That year, he and Van den Brande were introduced, discovering a shared interest in innovation, obsessive curiosity, and natural chemistry. “He is truly one of the smartest guys I’ve ever met in my life,” Van den Brande said. In addition to being impressed by the ex-Morgan Stanley banker’s intellect, the Hummingbird general partner was also intrigued by Gelenbe’s take on a burgeoning startup ecosystem. Though raised in Paris, Gelenbe had Turkish roots. That connection had given him a chance to see some of Turkey’s early successes and meet the country’s promising entrepreneurs. Intrigued by Gelenbe’s comments, Van den Brande decided to head to Istanbul to assess the market for himself. In Turkey, Van den Brande quickly found the anomalous shells he had sought in Western Europe at Big Bang Ventures. “I started to see the kind of founders I was looking for all my life.” Demet Mutlu was one example. When Van den Brande met the young founder, she had just returned to Turkey after a stint in New York. As she told him, she planned to build an e-commerce business, though she had yet to start. Despite the project’s nascency, Van den Brande was keen to understand Mutlu’s projections. “I said, ‘How much revenue will you do in the first year?’ And she said, ‘One hundred million.’ And I said, ‘Oh really? How? Why? And her answer was, ‘Because I will.’” Silence. Mutlu offered no more. “I hadn’t seen founders like that in Europe. If we think about founders willing to please VCs – that didn’t count here. If your answer is, “Because I will” and you don’t even give an explanation, you’re not going to give me anything.” To Van den Brande, the combination of dizzying self-confidence and ferocity portended a fearsome entrepreneur – someone who would not be easily knocked off course. Regrettably for Hummingbird, however, Van den Brande chose not to invest. Mutlu’s company, Trendyol, became Turkey’s first decacorn and was last valued at $15 billion. Thankfully, Van den Brande soon found a similarly unusual entrepreneur. Pamir Gelenbe provided the introduction. Sidar Sahin had a long entrepreneurial track record. In the early 2000s, he started a couple of successful gaming companies before attempting several other startups. Not all succeeded. As Sahin told the Wall Street Journal in 2012, “I have started many companies. Most of them failed.” Those failures came at a financial and personal cost. “I burned more than $10 million of my own money. I would see a good model and copied it. I tried to build a social network because Facebook wasn’t here in Turkey then. But you cannot do it if you have ego and a focus problem. I hit the wall big time, then again, then again. I said enough. I learned a lot about myself, but it was hard.” Those difficult moments may have marked Sahin, but they did not deter him. By the turn of the decade, he was ready to return to the arena. He started by helping Trendyol get off the ground, assisting Mutlu as a co-founder. While Mutlu’s firm grew rapidly, Sahin’s passion for gaming meant he quickly set his sights on building another business in the space. He called it Peak Games. At one level, Peak Games began with a simple premise. In 2010, Zynga demonstrated the potential in “social gaming,” leveraging Facebook to become a mass-market megahit. Sahin saw potential in a similar approach aimed at geographies Zynga had yet to penetrate. Sahin had grander ambitions than simply building a business, however. “I started Peak to change the world,” the founder shared in the same interview. In particular, he hoped that by creating a successful, high-performance business in Turkey, he could help seed an ecosystem. “It is about changing something in Turkey. The only way to do this is to build product and engineering-focused companies in Turkey,” Sahin added. An admirer of PayPal’s talent density, Sahin hoped that someday, Peak might produce a “Mafia” of its own. This was the founder that Van den Brande met in 2010. Over several meetings, he assessed the investment opportunity in front of him. Before continuing, pretend for a moment that you are in the Hummingbird investor’s shoes. You meet an entrepreneur who has had both successes and failures. He is now building a new company, Peak Games, that seeks to capitalize on the “social gaming” market, a category that piggybacks off social media platforms like Facebook. It is competitive, with Zynga already three years old. He has a big, lofty vision. You find him slightly awkward. You ask some questions. You learn about his past. About his wins and losses. You talk to references – they are unspectacular. You learn he has raised no money, and knowing the immaturity of the Turkish venture market, you can be confident that no capital will rush in. What do you do? If you have your filter attuned just so, if you can separate signal from noise, you will hear the drive behind these details. You will hear someone who overcame hard times to arrive at this point; someone capable of building impressive things but not being sated by it; someone with a chip on their shoulder; someone who sees the world differently and will not rest until they tilt it at least one degree in the direction of their choosing. “He had this intensity and clock speed which had us think he would swim across the Bosphorus every day if he needed to,” Van den Brande said. Van den Brande had yet to formalize his founder filter, but in Sahin, he discovered an arresting template, a first draft upon which a thesis would be built. “Sidar’s qualities are now woven into our founder’s thesis,” he said. In November of 2010, Hummingbird invested $500,000 into Peak Games, at a valuation of $2 million, pre-money, giving the firm a 20% stake in the startup. Puzzler

Kudos to Shashwat N, Steven C, Kelly O, Abhay G, Sunil S, Callum M, Adam P, and Andrew M for solving our last puzzler.

The answer? “Few.” Until next time, Mario You're currently a free subscriber to The Generalist. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Older messages

A Special Thank You – and Special Offer

Monday, November 27, 2023

Get a discount on everything The Generalist has to offer!

How do you hire upwards?

Tuesday, November 21, 2023

The OpenAI drama has left a hole in the company's upper echelons. Its remaining leaders now face a daunting task that every founder must reckon with: recruiting exceptional senior talent.

Ask Mario: The VC bubble, the value of specialization, and business case studies.

Tuesday, November 14, 2023

The first edition of our new Q&A series.

Modern Meditations: Danny Rimer

Thursday, November 9, 2023

The Index Ventures partner on art, investing, and destiny.

The Braintrust: What should you have invested in sooner?

Tuesday, November 7, 2023

Eight unicorn founders reflect on product/market fit, working on Capitol Hill, hiring leaders, and maintaining mental health.

You Might Also Like

🚀 Ready to scale? Apply now for the TinySeed SaaS Accelerator

Friday, February 14, 2025

What could $120K+ in funding do for your business?

📂 How to find a technical cofounder

Friday, February 14, 2025

If you're a marketer looking to become a founder, this newsletter is for you. Starting a startup alone is hard. Very hard. Even as someone who learned to code, I still believe that the

AI Impact Curves

Friday, February 14, 2025

Tomasz Tunguz Venture Capitalist If you were forwarded this newsletter, and you'd like to receive it in the future, subscribe here. AI Impact Curves What is the impact of AI across different

15 Silicon Valley Startups Raised $302 Million - Week of February 10, 2025

Friday, February 14, 2025

💕 AI's Power Couple 💰 How Stablecoins Could Drive the Dollar 🚚 USPS Halts China Inbound Packages for 12 Hours 💲 No One Knows How to Price AI Tools 💰 Blackrock & G42 on Financing AI

The Rewrite and Hybrid Favoritism 🤫

Friday, February 14, 2025

Dogs, Yay. Humans, Nay͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

🦄 AI product creation marketplace

Friday, February 14, 2025

Arcade is an AI-powered platform and marketplace that lets you design and create custom products, like jewelry.

Crazy week

Friday, February 14, 2025

Crazy week. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

join me: 6 trends shaping the AI landscape in 2025

Friday, February 14, 2025

this is tomorrow Hi there, Isabelle here, Senior Editor & Analyst at CB Insights. Tomorrow, I'll be breaking down the biggest shifts in AI – from the M&A surge to the deals fueling the

Six Startups to Watch

Friday, February 14, 2025

AI wrappers, DNA sequencing, fintech super-apps, and more. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

How Will AI-Native Games Work? Well, Now We Know.

Friday, February 14, 2025

A Deep Dive Into Simcluster ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏