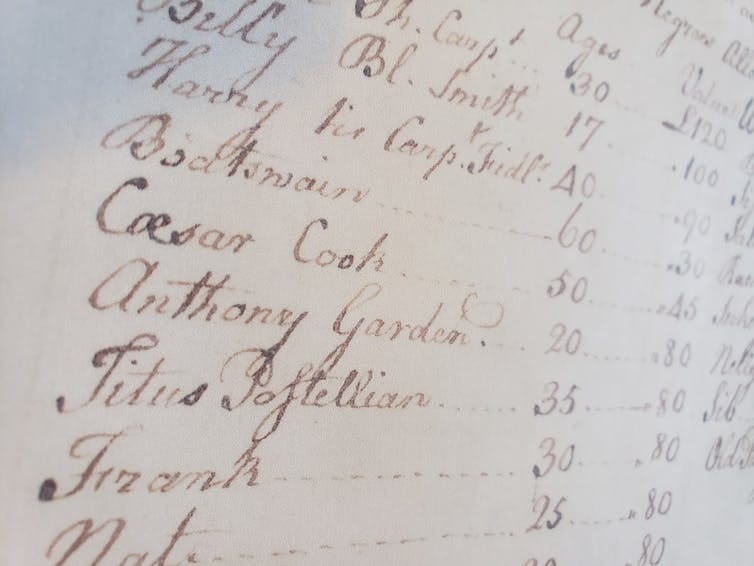

Oppression in the Kitchen, Delight in the Dining Room

|

Older messages

Increasing Racial Diversity without Affirmative Action

Friday, December 22, 2023

The author of a new book on affirmative action in higher education discusses how colleges might still be able to become more diverse now that affirmative action has been banned. OHF WEEKLY Increasing

Happy Holidays!

Friday, December 22, 2023

A message from the OHF Weekly editors, “Increasing Racial Diversity without Affirmative Action,” and a quote by Amanda Gorman. OHF WEEKLY Happy Holidays! By The OHF Weekly Editors • 21 Dec 2023 •

Congressional Anti-Intellectualism Draws Blood, Again

Sunday, December 17, 2023

During a recent six-hour grilling, a new reality emerged: Attitude now gives license to punish others — a way of being that re-concretizes a pigmentocracy's values. OHF WEEKLY Congressional Anti-

Should White Folks Be Silent about Racism?

Saturday, December 16, 2023

OHF WEEKLY, Vol. 5 No. 42: Editor's Letter; Articles on Why Orgs Fail at DEI, the Holidays and the Enslaved; Racism in Public Education; A Course on How Newspapers Covered Lynchings; and a quote by

Why Organizations Fail at DEI

Friday, December 15, 2023

It takes more than simply hiring someone to address issues within an organization. It takes a top-down commitment to be part of that change. OHF WEEKLY Why Organizations Fail at DEI By Lecia Michelle •

You Might Also Like

Red Hot And Red

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

What Do You Think You're Looking At? #204 ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

What to Watch For in Trump's Abnormal, Authoritarian Address to Congress

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

Trump gives the speech amidst mounting political challenges and sinking poll numbers ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

“Becoming a Poet,” by Susan Browne

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

I was five, / lying facedown on my bed ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Pass the fries

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

— Check out what we Skimm'd for you today March 4, 2025 Subscribe Read in browser But first: what our editors were obsessed with in February Update location or View forecast Quote of the Day "

Kendall Jenner's Sheer Oscars After-Party Gown Stole The Night

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

A perfect risqué fashion moment. The Zoe Report Daily The Zoe Report 3.3.2025 Now that award show season has come to an end, it's time to look back at the red carpet trends, especially from last

The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because it Contains an ED Drug

Monday, March 3, 2025

View in Browser Men's Health SHOP MVP EXCLUSIVES SUBSCRIBE The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because It Contains an ED Drug The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because It

10 Ways You're Damaging Your House Without Realizing It

Monday, March 3, 2025

Lenovo Is Showing off Quirky Laptop Prototypes. Don't cause trouble for yourself. Not displaying correctly? View this newsletter online. TODAY'S FEATURED STORY 10 Ways You're Damaging Your

There Is Only One Aimee Lou Wood

Monday, March 3, 2025

Today in style, self, culture, and power. The Cut March 3, 2025 ENCOUNTER There Is Only One Aimee Lou Wood A Sex Education fan favorite, she's now breaking into Hollywood on The White Lotus. Get

Kylie's Bedazzled Bra, Doja Cat's Diamond Naked Dress, & Other Oscars Looks

Monday, March 3, 2025

Plus, meet the women choosing petty revenge, your daily horoscope, and more. Mar. 3, 2025 Bustle Daily Rise Above? These Proudly Petty Women Would Rather Fight Back PAYBACK Rise Above? These Proudly

The World’s 50 Best Restaurants is launching a new list

Monday, March 3, 2025

A gunman opened fire into an NYC bar