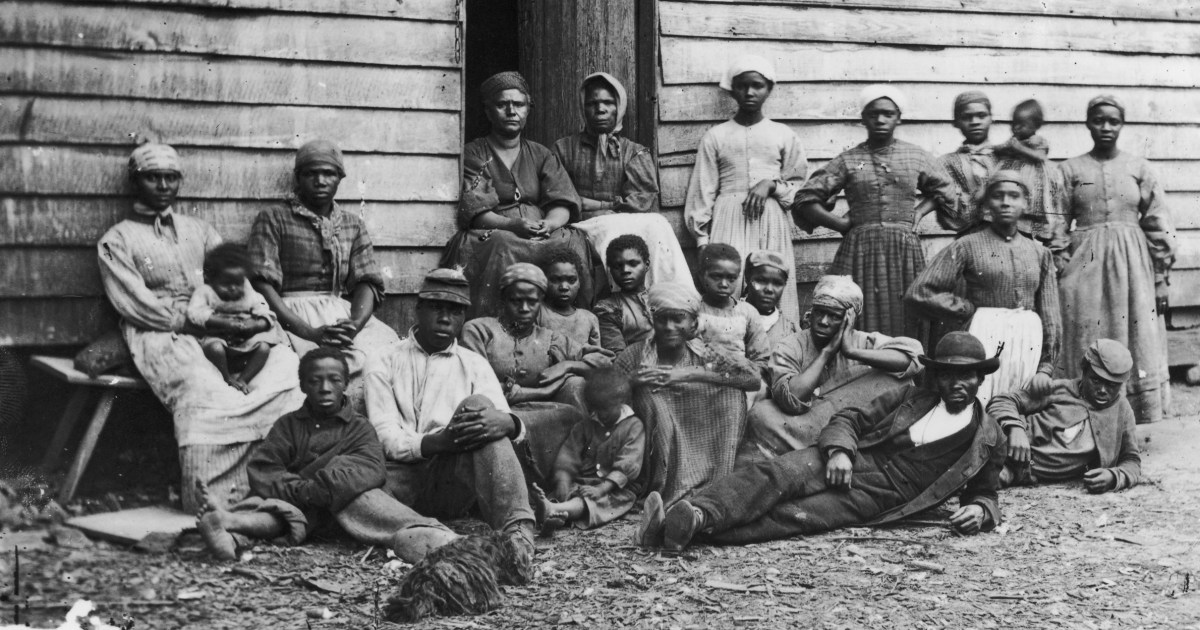

Why Black History Month 2024 is the Most Important Ever

|

Older messages

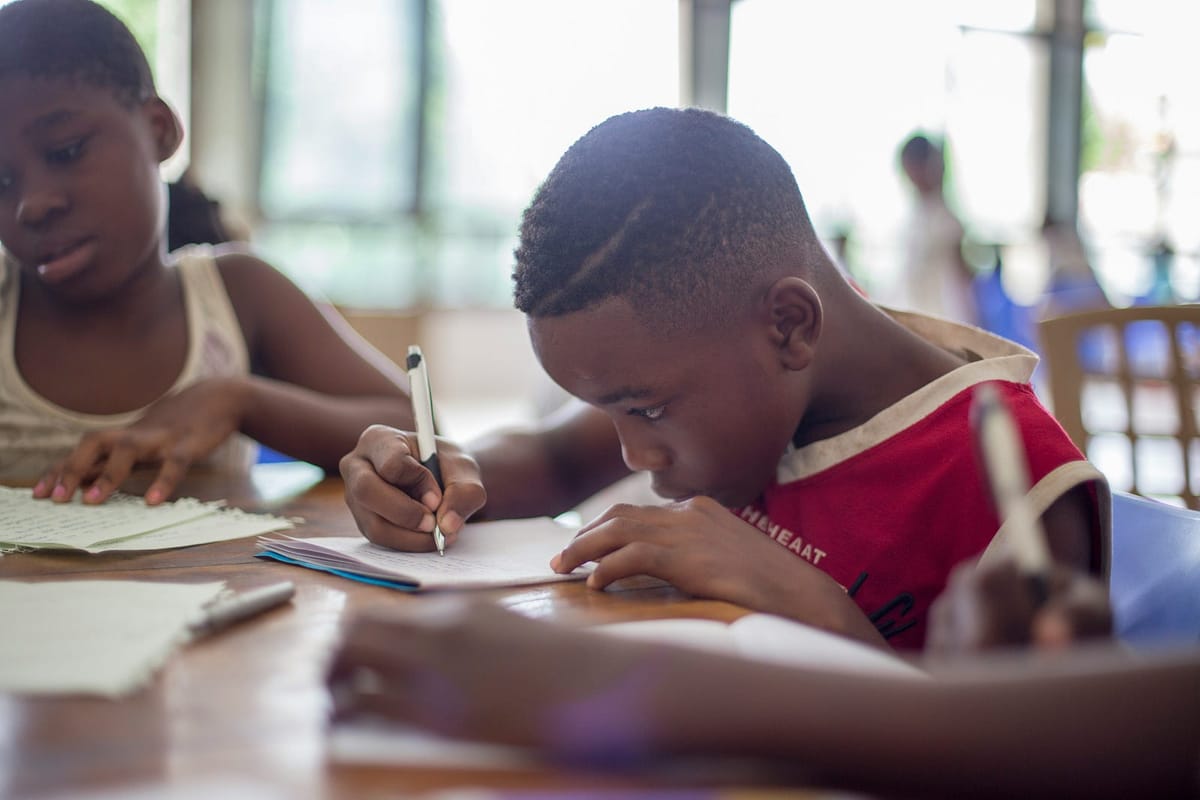

Black History Yesterday, Today, and Forever

Monday, March 4, 2024

OHF WEEKLY VOL 6 NO 3 On Black History writ large and small in the world and in our lives. OHF WEEKLY Black History Yesterday, Today, and Forever By The OHF Weekly Editors • 10 Feb 2024 • Comment View

Happy Valentine’s Day!

Monday, March 4, 2024

Fond Valentine's Day wishes to you and your beloveds, a poem by luminous Nikki Giovanni, and links to articles on love–OHF Weekly style. OHF WEEKLY Happy Valentine's Day! By The OHF Weekly

Anti-Racism 101: Own Your Racism

Monday, March 4, 2024

Point out sexist or homophobic behaviour, and white people will try to laugh it off. But racism? They're outraged. Most of us will declare we're anti-racist, but few of us are actively anti-

Anger, Racism, and Black Women

Monday, March 4, 2024

OHF WEEKLY, Vol. 6 No. 4 Editor's Letter, Frederick Douglass: An American in Ireland (Parts I, II, and III), “Anti-Racism 101: Own Your Racism,” “Let's Talk Black Excellence, People,” and a

“So Tell Me, What Type of Racist Are You?”

Monday, March 4, 2024

💛 OHF WEEKLY, A Tapestry Poem OHF WEEKLY “So Tell Me, What Type of Racist Are You?” By Jesse Wilson • 25 Feb 2024 • Comment View in browser View in browser Photo by Fares Hamouche on Unsplash 💛 OHF

You Might Also Like

Kendall Jenner's Sheer Oscars After-Party Gown Stole The Night

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

A perfect risqué fashion moment. The Zoe Report Daily The Zoe Report 3.3.2025 Now that award show season has come to an end, it's time to look back at the red carpet trends, especially from last

The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because it Contains an ED Drug

Monday, March 3, 2025

View in Browser Men's Health SHOP MVP EXCLUSIVES SUBSCRIBE The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because It Contains an ED Drug The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because It

10 Ways You're Damaging Your House Without Realizing It

Monday, March 3, 2025

Lenovo Is Showing off Quirky Laptop Prototypes. Don't cause trouble for yourself. Not displaying correctly? View this newsletter online. TODAY'S FEATURED STORY 10 Ways You're Damaging Your

There Is Only One Aimee Lou Wood

Monday, March 3, 2025

Today in style, self, culture, and power. The Cut March 3, 2025 ENCOUNTER There Is Only One Aimee Lou Wood A Sex Education fan favorite, she's now breaking into Hollywood on The White Lotus. Get

Kylie's Bedazzled Bra, Doja Cat's Diamond Naked Dress, & Other Oscars Looks

Monday, March 3, 2025

Plus, meet the women choosing petty revenge, your daily horoscope, and more. Mar. 3, 2025 Bustle Daily Rise Above? These Proudly Petty Women Would Rather Fight Back PAYBACK Rise Above? These Proudly

The World’s 50 Best Restaurants is launching a new list

Monday, March 3, 2025

A gunman opened fire into an NYC bar

Solidarity Or Generational Theft?

Monday, March 3, 2025

How should housing folks think about helping seniors stay in their communities? ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

The Banality of Elon Musk

Monday, March 3, 2025

Or, the world we get when we reward thoughtlessness ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

“In life I’m no longer capable of love,” by Diane Seuss

Monday, March 3, 2025

of that old feeling of being / in love, such a rusty / feeling, ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Your dishwasher isn’t a magician

Monday, March 3, 2025

— Check out what we Skimm'd for you today March 3, 2025 Subscribe Read in browser Together with brad's deals But first: 10 Amazon Prime benefits you may not know about Update location or View