|

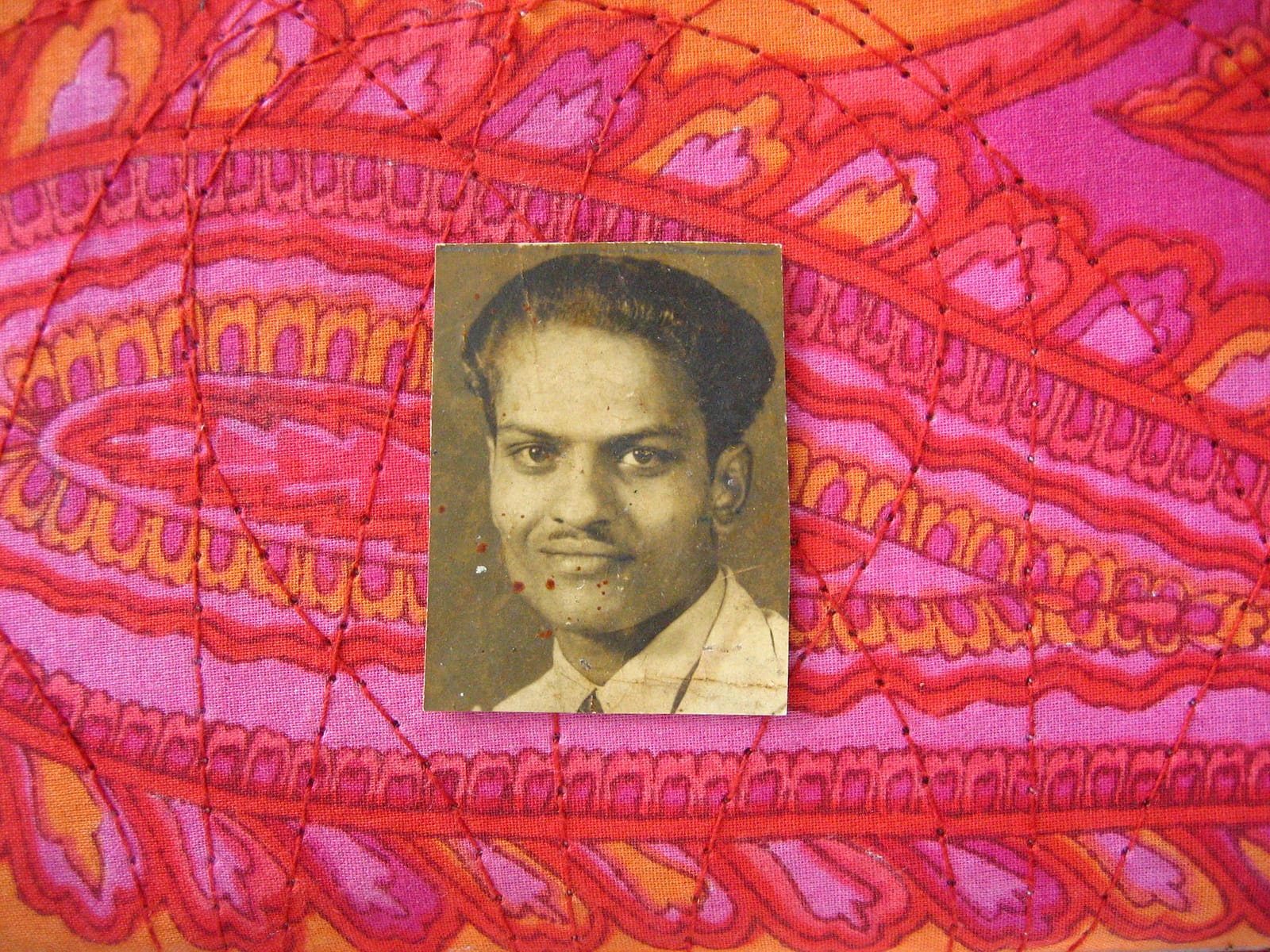

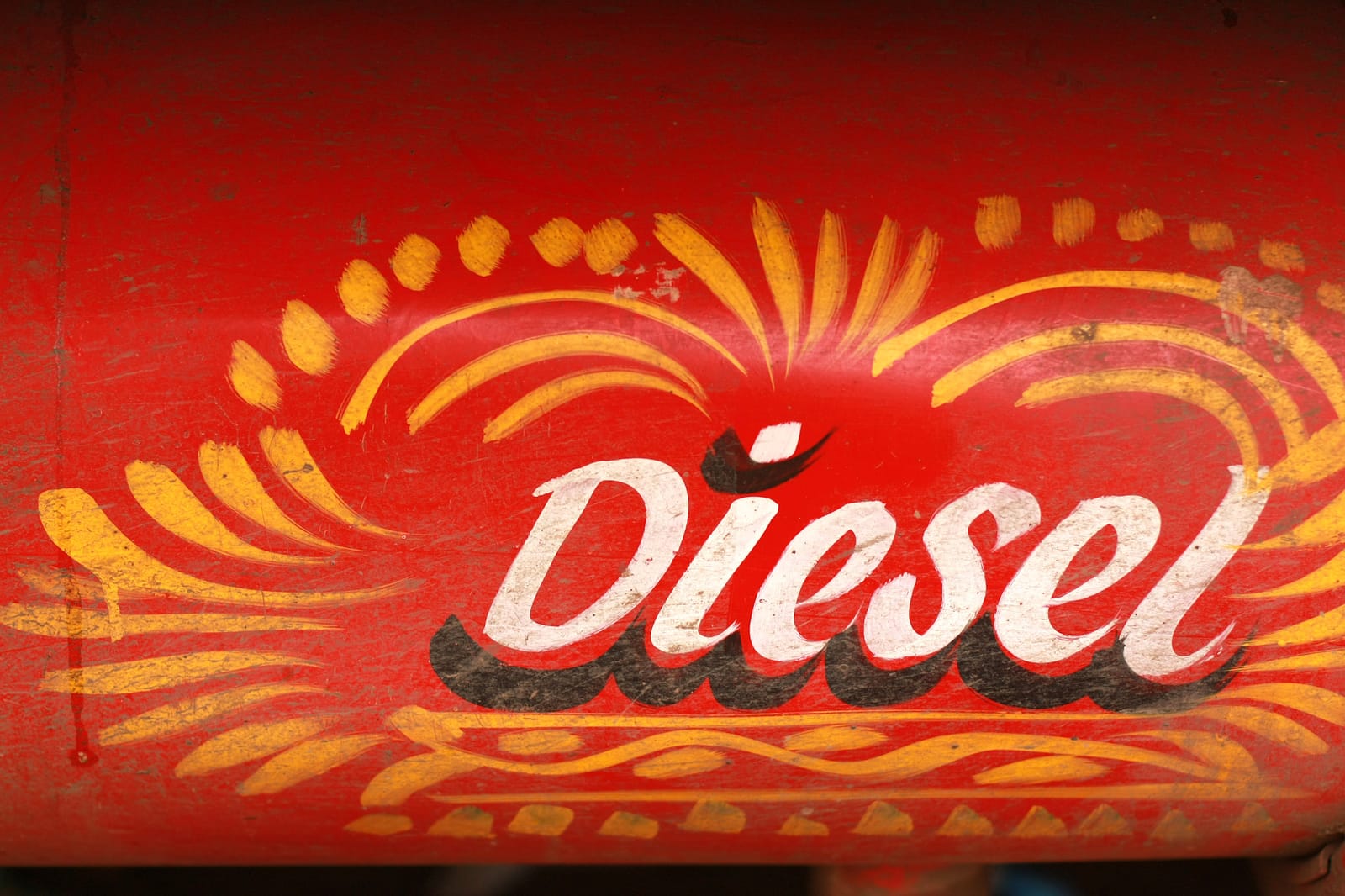

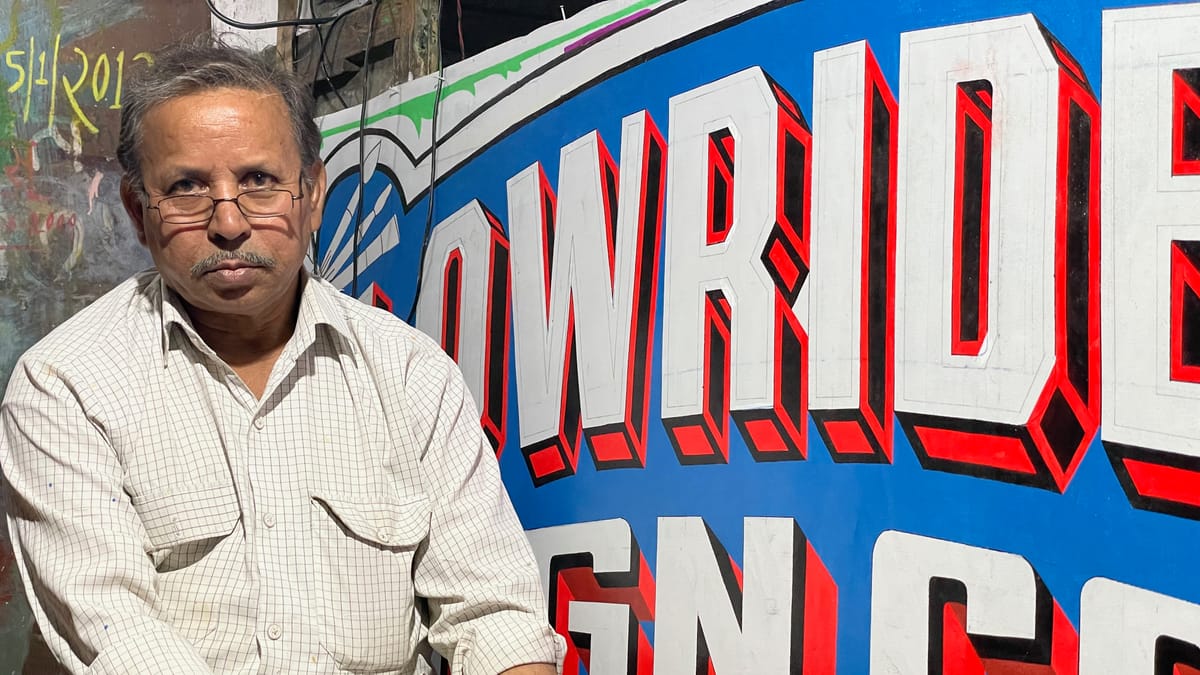

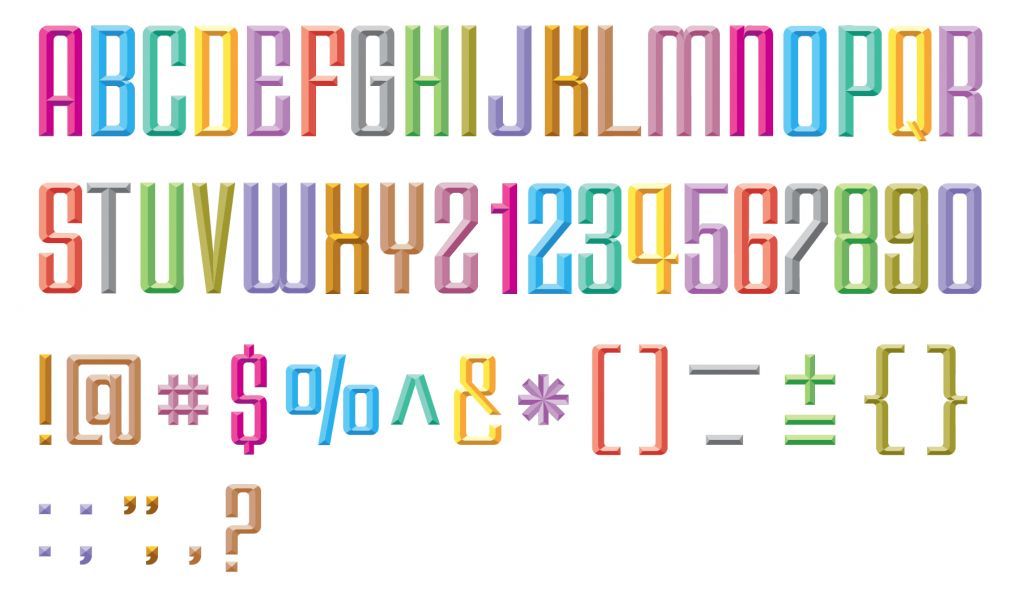

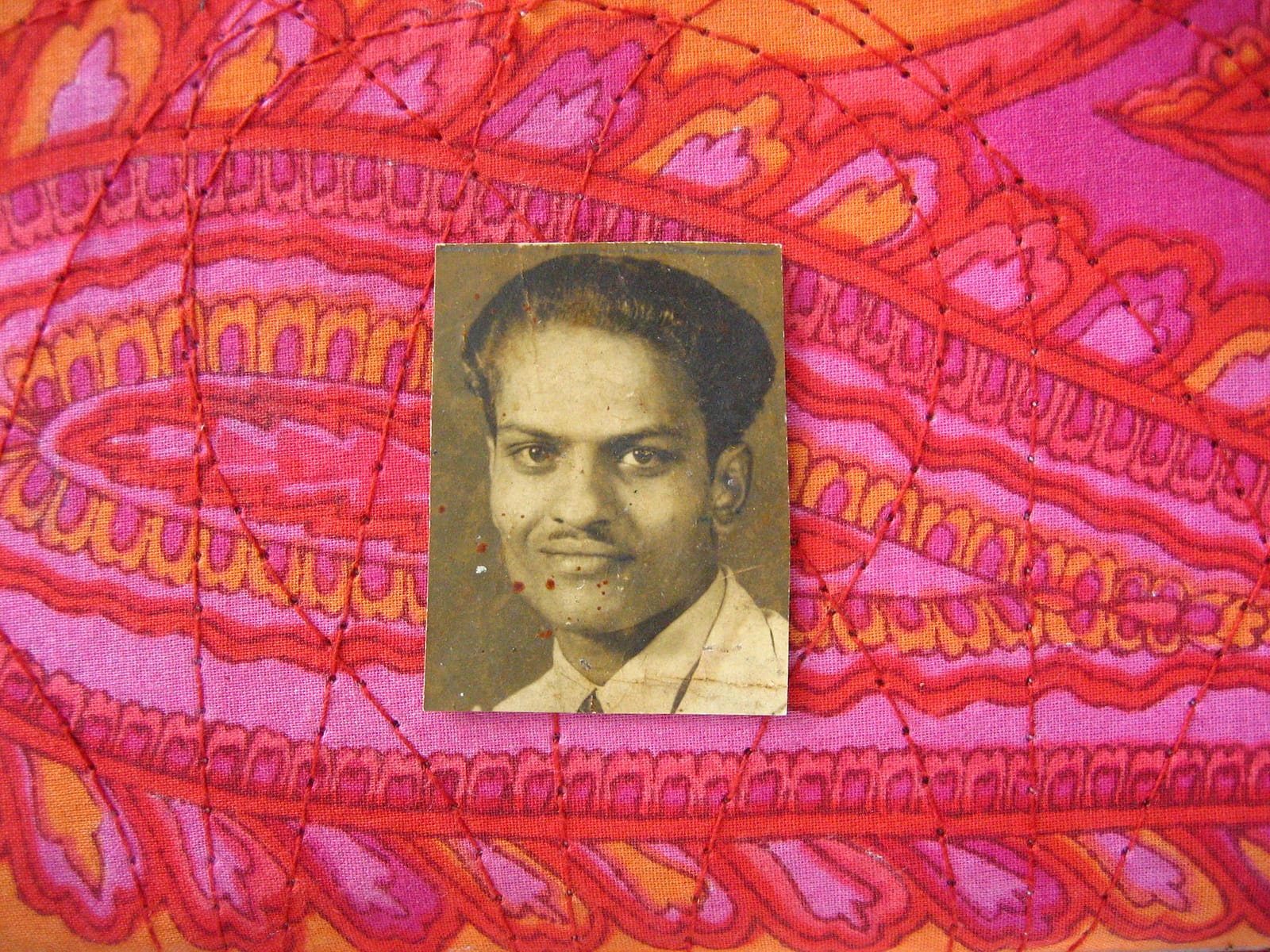

I've long been in awe of the sign painting in India and, for the London screenings of Sign Painters, I paired the film with Shantanu Suman's wonderful Horn Please documentary. I was therefore chuffed when Jill Strong sent me a LAB magazine article by Meena Kadri which included a wonderful set of photos from her travels on the subcontinent. I invited Meena to adapt the article for BLAG, which I'm delighted to share below. Sign-Wallas: An Exploration of Graphic Exuberance in the Indian StreetscapeText and all photos by Meena Kadri.  Truck painter at Wadi Bunder, Mumbai. Indian streets are a constant source of visual chatter, with varied voices that compete for our attention. This can be seen in the multitude of signs that one is confronted by on urban streets. Anyone can advertise, attract, instruct and inform—and such intentions find diverse expressions in street-based graphic signage. The desire to decorate and embellish is evident everywhere, from temples to taxis, minarets to match boxes, palaces to painted signs. Not much escapes decoration and often the mundane is elevated through the painter’s brush. Decorative devices can be understood as a kind of sweetener—a sort of coping mechanism to counter the sometimes challenging realities of existence in India.  Juice stall, Delhi. Customise and CommunicateA factor driving the flamboyance of Indian lettering is the desire to customise: humans crave belonging, but also strive to differentiate. In such a profound population pool, the drive towards standing out from the crowd, while maintaining shared expressive boundaries, provides a continued source of stimulation for sign painters. Clarity of communication takes on a central role in a society that continues to strive for higher literacy. Lack of a single shared language creates an additional challenge. Hindi, the country’s official language, is the mother tongue of just 45% of the population, and there are a further 28 languages that are spoken by more than a million people each. Many Indians understand English at a basic reading level, and its prolific use can be noted in signage across the country.  Truck painting, Ahmedabad.  Truck painting, Pondicherry Letters on the MoveThese issues somewhat explain the simple, direct nature of the language of many Indian signs. 'Horn Please OK' would be the classic example. It is painted on trucks to encourage vehicles to sound their horns while passing. This simple phrase serves its purpose well: to communicate clearly on an issue of safety. In southern India the same message has been abbreviated simply to 'Sound Horn'—though the economy of expression is still accompanied by a dose of the decorative. Earlier, artists were commissioned by the British and upper classes for portraits or religious imagery. The late nineteenth century saw painters producing imagery that increasingly served commercial interests, as artists adapted to emerging applications for their skills. What changed was that the city became the canvas.  Cycle rickshaw decoration, Delhi. Here we see some custom lettering techniques used on Delhi cycle-rickshaws. You would never find two designs the same. Each salutes a different owner or driver with a unique identity. At the beginning of my time working in India at the National Institute of Design, I saw the arrival of the compulsory new natural gas-powered rickshaws in Ahmedabad. When they first started appearing they were bare, new, and identical. Two years later, I had witnessed a number of styles of decoration and typography catch on as drivers sought to customise their vehicles in new and bolder ways. These evolving graphic fashions and techniques provide vibrant food for the urban Indian eye that craves novelty as much as it respects tradition. Styles can also locate vehicles as being from a certain place. In a country as vast as India, regional identity is vibrantly evident through varied graphic styles. Sign-WallasTruck painting at Wadi Bunder, Mumbai The men behind these graphic and signage works are called 'sign-wallas' or 'graphic-wallas'. This kind of half-English, half-local phrase is common in Indian speech and reflects a tendency to assimilate imported influences. ‘Walla’ means someone who provides particular goods or services: rickshaw-walla or music-walla. Sign-wallas create all sorts of visual communications from full wall advertisements, to smaller signs, to hand-painted number plates.  Taxi decoration, Mumbai. Some of them specialise in sticker-cutting, where they use sheets of coloured adhesive arranged to form creative typography and graphic embellishments. These designs are commonly applied to rickshaws, taxis, and other vehicles, and have the added bonus of providing moving advertisements for a sign-walla’s skill. Many men’s talents and individual styles are recognised in this way and so vehicular signage is therefore bound up with the expression of creative ego and often exhibits a kind of visual bravado.  Bollywood mudflap by Bobby Painter, Ahmedabad. This Bollywood mudflap example is recognisable to locals in Ahmedabad as being executed by renowned sign-walla Bobby Painter and clients seek him out with respect for his flair and his particular style of painting*. From the Street, For the StreetMuch of the staying power of sign-wallas is due to the fact that many are working directly on the pavement and so have a direct connection with their customers and the communication context. While potential clients may be lured by technological advances, many still prefer the personable style of service of the humble streetside sign-walla. Sign-wallas usually work from the sidewalk or in small roadside stalls. By working ‘from the street, for the street', sign-wallas gain a certain respect that is not extended to digital output service providers which operate on the ‘time is money’ premise. Being part of street culture, sign-wallas do not suffer the isolation that many people feel from office-bound existence. Often they have regular visitors who come and chat and drink tea with them throughout the day while they work. In this way their lives are as embedded in the street as their works. Changing TimesA number of men speak fondly of the old days of abundant work. Some started out doing more varied work such as commissioned portraits, which were still popular in the 1960s. Some are now relegated to doing mostly number plate signage, which provides a small but constant source of roadside income. Busier men often recruit their sons to help out and so the trade continues to be largely passed on through families. Changes in technology have continued to challenge working methods as with anywhere else in the world. Stickercutting, which used to be completely manual, can now be done with machines. Although many sign-wallas lament the decrease or change in work since digitally-output signage has hit the scene, others have diversified through collaboration, combining output methods and offering a wider range of applications.  Painter Mr Patel senior, Mirzapur, Ahmedabad. An example: the Patel family of Mirzapur in Ahmedabad. The Patels have a fixed shop run by family members spanning three generations. Mr Patel senior (pictured above) and his son learned their hand-painting trade on the street, while Mr Patel junior has a Bachelor of Commerce from a local college. After graduating, he decided to join them and runs the business side while keeping up-to-date on new technology. The Patels collaborate with digital producers to provide a range of services—but the greatest profit margin is from the application of digitally-cut numbers and embellishments for vehicles. Brands on the Brush Coca Cola signage, Ahmedabad Global players like Coca-Cola have embraced the services of sign-wallas as part of their advertising strategy in India. Both digital and hand-painted signage ages quickly in the Indian climate, but weathered painting is perceived to work in favour of brands. It can make them seem embedded in the streetscape, as if they have had a long historical presence—a significant factor in a country where tradition is respected. This constant dialogue between the local and global is a prominent characteristic of contemporary Indian streetscapes.  Pepsi signage, Ahmedabad My favourite example of this is a Pepsi wall advertisement in Ahmedabad. This constantly gets covered with cow-dung cakes, which are set to dry and later used as fuel. This juxtaposition of the global and local, of the aspirational and traditional, of the mass-produced and hand-made is exemplary of the great diversity and pervasive ambiguity that is India.

*Bobby Painter passed away in 2023 after the original publication of this article, but his son continues to paint under his name. Text and all photos by Meena Kadri / @meanestindian. Meena Kadri explores the intersection of innovation, culture and social change via her consultancy Random Specific. She is based at the edge of paradise in New Zealand though continues to lecture and consult globally alongside engaging locally. Gallery

Everything at BLAG is made possible by the wonderful membership that pays for it. Join them today with $15 off the annual plan, which includes the latest issue of BLAG sent you anywhere in the world. More from IndiaIn addition to these links, also check out Pooja Saxena's talk on her India Street Lettering initiative via the recordings from BLAG Meet: Inside Issue 04. More Vehicles

|