Takeaways

Investing is about relative, not absolute performance

Technology competition is about relative, not absolute strength

Society is about relative, not absolute status

1. Don't bet on the most likely winner

Imagine you're an investment analyst [1].

Investment analysts research companies and decide which stocks to buy or sell. You've done your work on Tencent, a chinese internet company, concluding that the business, management, and macro trends all look good. Gaming and online entertainment will continue increasing in importance, the executive team is experienced, and population growth provides a tailwind for at least ten years.

|

You model all of that up in excel. Write a simple 5 page investment memo. Prepare 50 pages of backpocket complicated charts just in case [2].

Convinced of your brilliance and diligence, you pitch your boss on Tencent. You time your meeting perfectly, a little after he's been in the office, but before he's busy looking up summer vacation homes.

It seems to go well at first. Your boss is familiar with Tencent, having golfed with the brother-in-law of Tencent's COO. He agrees with all your points on the business, management, and macro. Great.

Coming to the end of your pitch, you're feeling good, and expect your boss to initiate a small position in Tencent. Instead, he sits back in his chair, re-opens his tabs on vacation homes, and tells you you've missed the point completely. Not so great.

What went wrong?

Where you screwed up was not considering what market consensus was. It's a mistake most retail investors make, and sometimes professionals as well.

Investing is a game of relatives, not absolutes. It's how the stock performs relative to expectations that determines whether you make above average returns or not.

All that research you did doesn't matter if it's widely known. By definition, that's already priced in to the market. What you need to show is what the market is missing, and why that misperception will correct itself. If you don't have an edge [3], your pitch is pointless.

It's why companies that post good numbers for their earnings reports can still see their stock price go down.

It's why you can get below average returns buying a great company that is priced to perfection, and why you can get above average returns buying a shitty one that was left for dead.

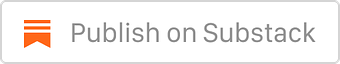

And it's why illegally knowing company earnings ahead of time doesn't mean you'll make money 100% of the time [4].

In investing, you want to bet on the mispriced horse, not the horse most likely to win.

|

This applies both at the micro level to individual stock pitches, and at the macro level to investment firm performances. Absolute skill doesn't matter. It's the fund's skill relative to competition that determines whether it can make above average returns.

It's why information such as credit card, app download, or satellite data is no longer a factor for outperformance, but table stakes.

It's why luck is playing a bigger role, since the dispersion in skill has been reduced.

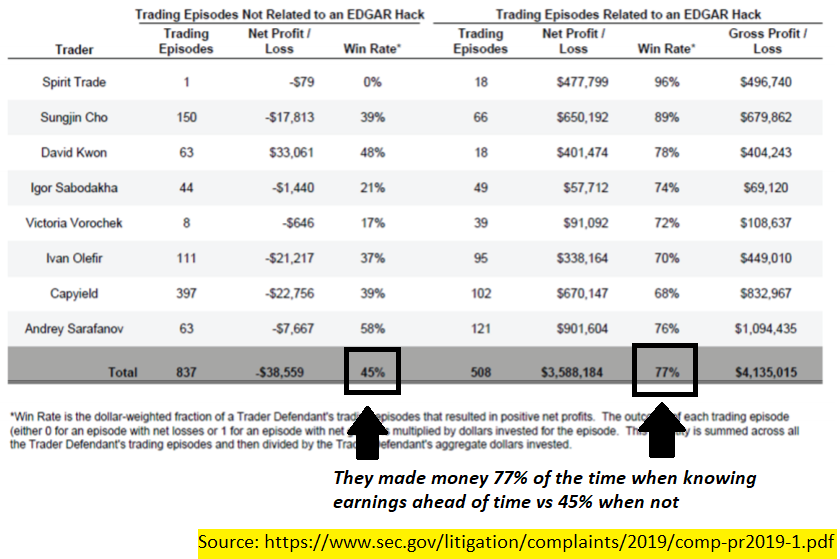

And it's why the overall outperformance (alpha) for hedge funds has stagnated, as more investors know best practices and frameworks.

In investing, it's all relative.

|

2. Your tech relative is an eight year old

Imagine you're at a tech company selling online widgets.

You've found an advertising channel that costs you $1 to acquire a customer, and each customer gives you $10 in lifetime value [5].

Seems like a great deal, so you start spending your marketing budget on it. It works, and you start looking up summer vacation homes to buy with the extra profit.

Except you start realising the number of customers you're getting keeps going down, implying your customer acquisition cost (CAC) keeps going up. After a while, you're barely breaking even on the customers. Summer vacation dreams dashed.

What went wrong?

Where you screwed up was not considering what the market equilibrium was. It doesn't matter how efficient your marketing spend was, if your competitors were more efficient than you.

They'll outspend you, acquire more customers, make more profit, and repeat. In the process, they'll force price efficiency on the market and you. You were optimising for the local maxima; everyone else was solving for the global maxima.

It's why knowing who your competitors are is critical for business survival. If you're happy with your offline CAC as a mostly offline business, you'd better hope someone doesn't dropship your product and raise your CAC. If you're happy with your online CAC as a mostly online business, you'd better hope someone doesn't open a retail store and close you down.

It's why relative market shares are more important than absolute. The difference in spend efficiency, not the spend efficiency alone, is what compounds over time for above average returns.

And it's why word of mouth and customer loyalty is important, since it allows you to temporarily defer the effects of relative comparisons. When CAC is at a $0 floor it's no longer the limiting factor [6].

|

This applies not just to customer acquisition, but to every part of the company, from the talent you hire to the quality of the product you make. Knowing their strengths alone without knowing how they compare against others isn't meaningful.

In the past, when information, people, and products travelled slower, this was less of a problem. Customers would compare you against the physically closest alternatives and call it a day.

Today, the relevant relative is everywhere and everything. You're competing against 8 year old toy reviewers and engineers outsourcing their own jobs to China so they can surf reddit. The effect of tech has reduced the importance of physical proximity.

It's the Red Queen hypothesis playing out, with companies needing to constantly find an advantage, and the race getting quicker every year. Discoveries get shared and commoditised over time, constantly eroding your advantage. Once you have no advantage, you earn average returns.

In tech, it's all relative.

3. Relatively speaking, the billionaire isn't rich

Imagine you're just trying to live your life.

No wait, you don't have to imagine, that's all of us.

You've read the self-help books, gone for that zen retreat, and watched that TED talk. They all tell you to focus on improving yourself, and be less obsessed with comparing against others.

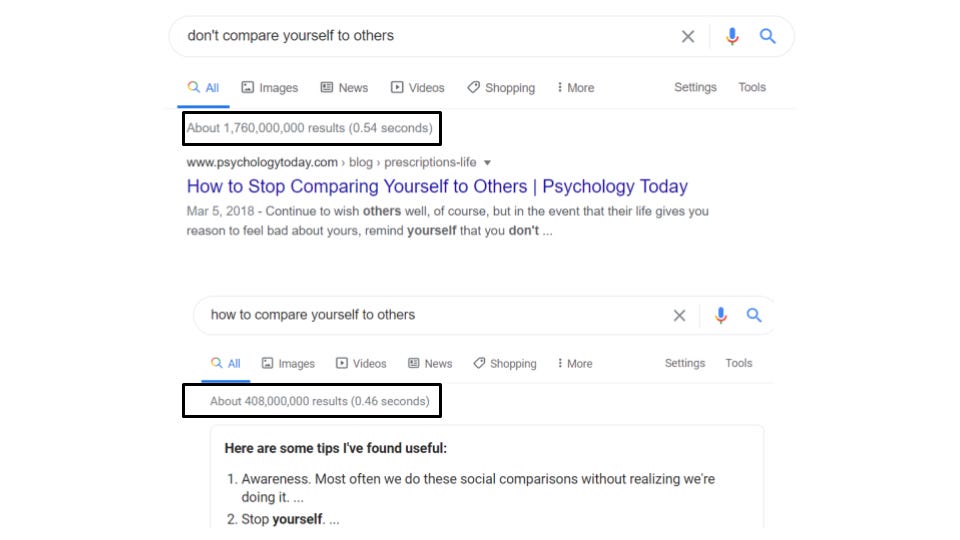

Even Google returns 1.8bn results for "don't compare yourself to others" vs 0.4bn for "how to compare yourself to others". And the top results for the latter are all articles on how to stop comparing.

|

And that's true. You should be focused on improving yourself, and trying to be 1% better every day.

But you already know where I'm going with this.

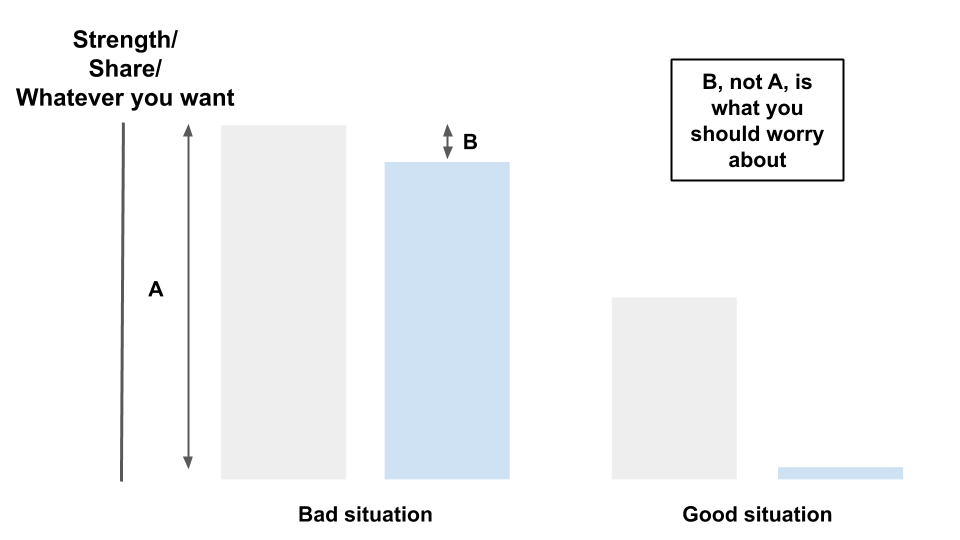

There’s a difference between what people say vs what they actually do. You can judge yourself on an absolute standard, but everyone else judges you on a relative one. Relative to their expectations of you, or relative to someone else.

Society is one big sorting algorithm [7].

It's why we like supporting the underdog, the turnaround story, or the long shot. We reward people for performing better than expected, and care less about people that perform as expected, even if they've been great all the while. There's even a whole bible parable about it, the prodigal son [8].

It's why we obsess over quantifiable metrics that can demonstrate our relative status to each other. Followers, likes, shares. As long as it's something that can show where we rank in comparison, we'll always desire it [9].

And it's why Goldman Sachs CEO and billionaire Llyod Blankfein doesn't feel rich, since he's comparing himself against his multi-billionaire friends.

What should you do then?

Under promising and over delivering seems to be a popular way to go. People sandbag expectations and anchor others to lower performance because it works [10].

Choosing your own set of competitors to compare yourself against might be another way. If you're not happy with your peer set, there's a billion people out there to swap with.

And you should still seek to measure yourself by your own scorecard, and get better for its own sake. Just know that it's not how others are measuring you.

In life, it's all relative.

Other

Jukebox is an AI that makes music. Check out a re-rendition of Ella Fitzgerald

Higher reputation sellers are less likely to take advantange of shortages in supply by price gouging

"The SEC is basically saying 'spring loading' is legal insider trading."

Shoutouts

Shoutout to reader Ben for correcting my bad math on the Li Lu investing post regarding the carry calculation

If I was still in high school, I'd be applying to the Progress Studies for Young Scholars program with speakers such as Tyler Cowen and Patrick Collison. Seems it's open for adults to audit as well.

Question of the month

What’s a controversial idea you’d like to get another point of view on? Reply directly to this email and I might write about it in future newsletters.

Footnotes

Some of you probably are. I'm referring to buyside analysts here, not sellside (who research but don't invest for the firm) or investment banking analysts (contrary to the name, don't invest at all)

An investment memo is a write up on the stock you're pitching, commonly used in the investment industry as a way to summarise your idea.

One framework for investment edge is the information, analysis, or time horizon framework that John Huber uses

From page 34 of the pdf. See this paper by Chloe Xie that further shows the low (bad) signal to noise ratio on those trades

Simplistically put, every customer pays you $10 for every $1 you're spending on them

I suppose you can have negative CAC, where you're paid by someone else to acquire paying users, in some three party situation. I've not seen it much, but do let me know if it's a quirk of the industry you're in.

A sorting algorithm is a program that puts items in the order that you want, a fundamental part of programming

A father has 2 sons, one good and one bad. The bad one leaves home to have fun, loses all his money after many years, and comes back in shame. To the surprise of both the sons, the father welcomes the bad one home with a party. The father says that the bad son was lost and now is found, and that's worth celebrating, whereas the father viewed all that he had as already belonging to the good son. The good son takes all the money and moves to Paris, making the father realise he shouldn’t have said that. I might be misremembering the moral of the story.

Reddit users make up stories to get “karma points” when everything’s made up and the points don’t matter. Even the societal rejects like hikikomoris will still desire some status, such as commenting online about which anime series is superior and reflects better taste of the viewer.

There is a study that disputes this advice, claiming it has no significant impact