Astral Codex Ten - Book Review: From Bauhaus To Our House

Like most people, Tom Wolfe didn’t like modern architecture. He wondered why we abandoned our patrimony of cathedrals and palaces for a million indistinguishable concrete boxes. Unlike most people, he was a journalist prone to deep dives into difficult subjects. The result is From Bauhaus To Our House, a hostile history of modern architecture which addresses the question of: what happened? If everyone hates this stuff, how come it won out and took over the built environment? How Did Modern Architecture Start?European art in the 1800s might have seemed a bit conservative. It was typically sponsored by kings, dukes, and rich businessmen, via national artistic guilds that demanded strict compliance with classical styles and heroic themes. The Continent’s new progressive intellectual class started to get antsy, culminating in the Vienna Secession of 1897. Some of Vienna’s avante-garde artists officially split from the local guild to pursue their unique transgressive vision. The point wasn’t that the Vienna Secession itself was particularly modern… …so much as that it created a new romantic vision of the Artist. The Artist was a genius, brimming with bold new ideas that the common people could never understand! The Artist defied the norms of bourgeois society! The Artist was part of some official collective with their own compound in a trendy part of the city! The compound produced manifestos explaining why their vision of Art was better than everyone else’s! This romantic vision was so powerful that you could become a well-regarded artistic movement just by doing the collective, the compound, and the manifesto especially well. Whether or not you produced art was of secondary importance - the sort of question that a bourgeois who didn’t understand your true genius would ask. At the same time, Europe’s intelligentsia was falling in love with socialism. There was an inevitable wave of new socialist art compounds, each writing a manifesto explaining why their new artistic movement was the one that truly threw off the shackles of capitalism and represented the proletariat. First among these was Bauhaus, founded by Walter Gropius in Germany in 1919. Their big idea was “starting from zero” - since all previous art had been contaminated by capitalism, we needed a hard reset where people started by (eg) contemplating what color and shape really were, then gradually building a new socialist art from the ground up. This new art must eschew ornamentation, associated as it was with kings and nobles who had money to spare on gold trim or sculpted curlicues. Real socialist art would be brutally functional, the sort of thing a poor worker might build. If this sounds harsh, remember that this was right after World War I, the old order stood infinitely discredited, and starting from zero must have seemed pretty appealing. Maybe too appealing: the Bauhaus wasted no time in becoming a caricature of itself. Someone got into their head that pointed roofs “represented the crowns of the old nobility”; henceforward, all their buildings had flat tops (even though this was unsuited for the snowy German climate). Facades were fake, just like the fakeness of bourgeois propaganda; therefore true socialist buildings would show their innards as much as possible, with jutting pipes and undecorated structural supports. Imagine for a moment the 2024 equivalent of Bauhaus. Someone has just started the woke artists’ collective, claiming to perfectly encapsulate all the principles of wokeism and be the wokest people around. What happens next? Obviously every other group of woke people accuse them of being racist, and they have bloody internecine feuds for the next twenty years, right? Right. No sooner had Bauhaus developed their new socialist architecture designed to utterly remove all traces of bourgeois influence from design forever, then all the other socialist artists said: “I dunno, seems kind of bourgeois”:

My favorite story along these lines: 1930s German architect Bruno Taut built housing with a red front, a reference to the Red Front communist paramilitary group. There was fierce debate. On the one hand, this was a pretty sweet communism pun. On the other hand, red was a bright color, and bright colors seemed too much like ornament/decoration, which were known to be bourgeois. Taut’s side lost, and “henceforth white, beige, gray, and black became the patriotic colors, the geometric flag, of all the compound architects.” So far this is what we would expect from an insular group of avante-garde socialists. The real question is - who hired these people? Often the answer was “nobody” - as long as you had a clever enough theory of the nonbourgeois, it didn’t really matter whether you built anything. Some of the most famous architects of this era never got a commission until late in their careers, or survived off a few commissions from friends and family. Other times the answer was “socialist governments”. For example, the socialist party got elected to local government in the German city of Stuttgart in 1927, and rewarded socialist artists with contracts to build worker housing - the first of what would later be known as “commieblocks”. Ironically, real workers hated the modernist styles, and could only be forced into them when there was nowhere else to go. The architects were unfazed. The Romantic ideal of the artist said that real artists considered their clients Philistines and paid no heed to their preferences; the less you cared about your clients’ opinion, the realer and more romantic an artist you were. There was a slight hiccup in adjusting this philosophy to socialism, but only slight: by this time, classical Marxist philosophy had already ceded to the Bolshevik idea of a “dictatorship of the proletariat” where communist-theory-educated elites needed to re-educate the workers into accepting their own class interests. Wolfe describes the overall effect in Stuttgart:

How Did It Take Over The Academy?A prophet is without honor in his own country - or, to put it another way, a disease rarely goes pandemic in the area where it evolved. You need a naive unexposed population before ideas can really explode. Enter the United States. In the early 1900s, the US still had a colonial inferiority complex. Europe automatically had the best and classiest of everything: the best intellectuals, the best food, and definitely the best art. A few bold Americans tried to blaze their own cultural trail, but they were overwhelmed by the power of elite Europhilia. After World War I, some Americans visited Europe and brought back reports that the Bauhaus was pretty cool. Some modern art museums did exhibitions on the Bauhaus. Everyone agreed that they were cooler and better than we were, but nothing really came of it. Then the Nazis took power in Germany. The Bauhaus architects - invariably socialist, often Jewish - fled the country. Many came to America, where we colonial yokels responded with star-struck awe. Wolfe, writing before political correctness limited our stock of acceptable metaphors, says:

The awed colonials immediately gave them every prestigious architecture position in the country. Gropius got the department chair at Harvard. As for Mies, the last director of the Bauhaus collective in Germany:

And so:

I found this part of the book sudden and jarring. Okay, Americans have always had an unhealthy fascination with European culture - but, really? Everyone abandoned all previous forms of architecture within a three year period just because some cool Europeans showed up? I was left to hunt down hints to the broader story. Some of these come from elsewhere in the book, and some are my own speculation. First, the Bauhaus promised architects a promotion from tradesman to intellectual. Some, like Frank Lloyd Wright, had already started such a transition. But the average architect was just someone who knew some stuff about stone and columns and stuff. Rich people would hire one to build them a cool villa, they would make approximately the cool villa the rich person requested, and the rich person would pay them enough to make an okay living. But modernism told architects that they were not only brilliant romantic Artists in the style of Van Gogh or Picasso - they were also intellectuals. They had to be able to discourse on which styles were bourgeois, which expressed the true meaning of Light and Structure, and so on. Someone who wrote manifestos on the true meaning of Structure is automatically in the upper middle class; they get invited to cooler parties than somebody who just knows things about different types of stone. This was the Bauhaus’ offer to architects, and they leapt at the opportunity. Second, the first crop of European modern architects were incredibly charismatic and persuasive people. Gropius’ nickname was “The Silver Prince”; Wolfe describes him as “irresistibly handsome to women, correct and urbane in a classic German manner, a lieutenant of cavalry during [World War I], decorated for valor, a figure of calm, certitude, and conviction at the center of the maelstrom … [he] seemed to be an aristocrat who through a miracle of sensitivity had retained every virtue of the breed and cast off all the snobberies and dead weight of the past”. Meanwhile, his colleague, born Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, demanded that everyone refer to him as “Le Corbusier” (French for “The Crow-Like One”) as some sort of combination artistic pseudonym / branding / flex. How are normal humans supposed to compete with people like these? Third, modern architecture benefited from that most reliable of vectors for any bad idea: activist college students:

Fourth, and more speculatively (ie I’m making it up), maybe the first modern building in a city looks better than the nth? Imagine a city where most buildings look like this: …and then right in the middle, for the first time, somebody builds one of these: It must have been incredibly jarring and impressive, like an embassy from the future. Imagine that you’re Pepsi, Coke just built the glass building, and you’re still in the brick building. Doesn’t seem great. Fifth, one of the morals I took from The Rise Of Christianity is that you’re more likely to win if you’re in the game. Paganism was just a set of tools for propitiating deities; Christianity was a missionary religion. Except at the very end (eg Emperor Julian), pagans didn’t think of themselves as proud pagans or try to convince others of paganism - so Christianity, which understood that it was competing with paganism and tried to win the competition, succeeded almost by default. In the same way, older styles of architecture were just sets of tools for making pretty buildings. Its practitioners didn’t originally think of themselves as “old-style architects” or care about converting anyone else. But modern architecture, with its manifestos and compounds and nonbourgeoisity, was absolutely an ideology, and understood perfectly well that it was at war with its predecessors. Some of the most ideological bits were filed off before it came to America. In Germany, Bauhaus architects had tried to adhere to a special Bauhaus diet invented by Walter Gropius - that didn’t last long. But it was still recognizably a warrior faith. How Did It Get Clients?This is the question asked in From Bauhaus To Our House's famous introductory passage:

But even though it’s the framing device of the book, it barely gets addressed. One clue is that not everywhere went modern at the same rate. The average suburban house is still built in traditional styles, because home-buyers have no need to justify them to anyone but themselves. But corporations and governments have a more complicated mandate. When executive or bureaucrats make decisions, they’re supposed to be catering to more than their personal aesthetic taste. They’re supposed to be following best practices and doing what’s responsible, maybe as judged by a sort of “nobody ever got fired for buying IBM” type of standard. In architecture, the responsible-person standard was for big institutions that needed buildings to convene a Selection Committee including some representatives of the institution and at least one prestigious architect. But the representatives of the institution were out of their depth, and the prestigious architect could usually bully them into submission. So modernism it was. The problem was alienation - the people designing the buildings weren’t the ones residing in them - or, in many cases, even viewing them as they walked by. Wolfe thinks that the people with the most exposure were least happy with the results. Here’s his discussion of the Seagram Building, one of the first great International Style skyscrapers:

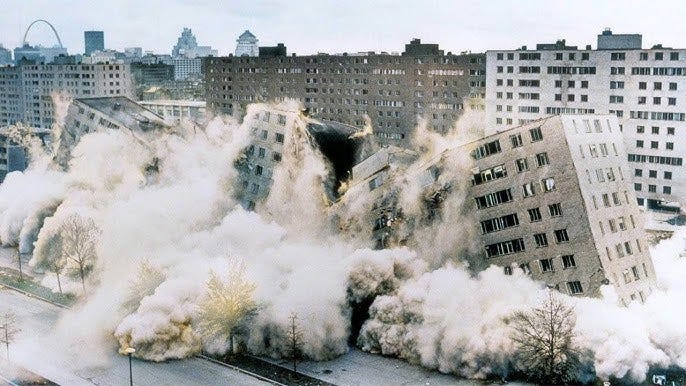

Predictably, modern architecture won its greatest victories among those who had the least opportunity to refuse: poor people in the projects. Wolfe writes especially of Pruitt-Igoe, a St. Louis public housing project designed by famous modern architect Minoru Yamasaki:

But Wolfe does admit that some rich people voluntarily selected, or even commissioned, modernist buildings. He blames trendiness. There was a pipeline from the architecture schools (now dominated by the modernists) to the architecture sections of newspapers and magazines (Wolfe blames Domus, House & Garden, and The New York Times Magazine in particular). Rich people would read the magazines, understand that modern architecture was “in”, and go with it so as to not feel “left behind”. Wolfe doesn’t mention this - writing in 1981, how could he? - but this was the height of the age of expertolatry. See my reviews of Revolt Of The Public and Seeing Like A State for more. The concept of “the experts are a corrupt priesthood and you can safely ignore them” hadn’t really entered mass liberal consciousness. The idea that hard scientists were real experts but everyone else was just kind of faking it was decades in the future - and the Modernists were nothing if not good at faking the mantle of science and reason. This was mostly psychological - but also partly structural. There was no Internet. If you thought modern architecture was ugly, but all the experts said it was beautiful, there was no Twitter where you could shout your opinion under the cloak of anonymity. Every household got the same few TV channels and the same few magazines, and their architecture sections were all written by professionals who were singing the new style’s praises. So what are you going to do? Go to a cool party and shout “I think the style that all the experts say is the sign of an uneducated philistine is actually better”? Would you really? Why Did It Stick Around?Grant that all of the above modernism gave modernism the potential to be an exciting late ‘40s / early ‘50s fad. Why did it endure? Wolfe points to three culprits: loss of expertise, cost-cutting, and continued academic dominance. To understand loss of expertise, let’s look at our Beaux-Arts building again: All that ornament - the gilded plaster, the cast iron balcony, etc - required trained artisans. These artisans aren’t completely gone - some of them were no doubt involved in the recent restoration of Notre Dame and other similar projects. But they’re no longer organized into giant corporations capable of decorating a whole city. Wolfe:

Last time we discussed this, a commenter agreed this was a big problem:

Cost-cutting was simple: cut out all the artisans, and buildings cost less. Sam Hughes at Works In Progress has done a great job showing that, contra the Baumolists, our modern industrial civilization could produce ornament cheaper than ever if we wanted to. But it’s even cheaper to not produce it. In the old days, cutting costs like this would have been unthinkable; your building would have stood out as an eyesore. But if every building is an eyesore, then spending extra on your building makes it look froo-froo, plus the extra money starts to seem irresponsible:

Finally, the academic architectural establishment was able to cancel anyone who proposed going back to the old ways. An architect who dared comply with a client’s request to add ornament would find themselves almost blacklisted. In 1954, architect Edward Stone¹ had a falling out with modernists and started to add some ornament to his building. Not much - they still looked like concrete boxes. But some of them were ugly concrete boxes with circles on them: According to Wolfe:

Wolfe recalls an incident from the beginning of his own career as an architectural journalist:

Another anecdote, this time on hotel architect Morris Lapidus²:

What Happened To It?One of my pet peeves is that when I tell a classy person I don’t like modern architecture, they’ll correct me - “Oh, I’m sure you don’t like Brutalism. But it’s unfair to hold that against the whole area. Why, surely even someone like you can appreciate the unique beauty of a von Shmendenstein, a Dazervaglik, or a Mihokushino.” Then I sheepishly admit that I’ve never heard of any of those people, and maybe I was overly hasty, and I should have been more careful and done my homework. They pat me on the head and say it’s fine. Then I’d go home and look it up and all those people’s buildings would be hideous. Wolfe earns my affection by calling this out. He admits that c. 1970 modern architecture split into a dizzying variety of styles - but also, that those styles were all similar and bad. By c. 1970, heretics in the style of Stone and Saarinen had mostly lost. How do you attack an invincible consensus? By claiming to be even more orthodox than your fellows. This was the insight of an architect named Robert Venturi, who spent most of his time writing incredibly erudite manifestos about how modern architecture wasn’t modern enough. Wolfe ties this to the contemporaneous rise of pop art. Modern art and architecture were founded in the rejection of bourgeois notions of beauty, in favor of a faux-proletarian idea of simplicity and scientificness. But, Venturi pointed out, proletarians were kind of thin on the ground in c. 1970 America. Grounding your class analysis in a non-existent proletariat seemed kind of out-of-touch, and so - perhaps - bourgeois. Who actually existed? The middle class. And what did the middle class like? Mass market consumer slop. Therefore, the true foundation of Art should be mass market consumer slop. Of course, since artists are infinitely superior to the middle class, it should be some sort of extremely complicated reference to mass market consumer slop which makes it clear that the artist themselves is infinitely above such things (but also, what if they weren’t above it, because they were so in-touch with normal people (but also, obviously they’re infinitely above it (but also, what if they weren’t))) . . . and so on. This tendency eventually became postmodernism with all its layers of irony and self-reference. In architecture, postmodernism relaxed the constraint that every building had to be a box, in favor of buildings that were “playful” and tried to “undermine” traditional notions of form and shape: Postmodern buildings were allowed to include some traditional elements and ornamentation, but only to refer to them ironically, confuse people about them, or mock them. Postmodern skyscrapers were still mostly ugly boxes - but with one weird feature, to show how playful they were being: Wolfe has a certain horrified admiration for Venturi. He thinks he was a master at going right up to the brink of heresy, jumping back before anyone could accuse him of anything, rushing back to the brink immediately, and cloaking his real opinions under so many layers of irony that nobody knew what to do with him. Since at this point architecture was mostly a manifesto game, and Venturi’s manifestos were cleverer than anyone else’s, he became a leader of the field:

After Venturi opened the floodgates, a whole host of new schools arose, including: The Whites, Le Corbusierian fundamentalists, named after their conviction that all buildings should be white: The Grays, followers of Venturi, named after their disagreement with the belief that all buildings should be white, and for sometimes creating gray buildings: The Rationalists, who thought that any architecture created while the bourgeois class existed was inherently bourgeois, and therefore architecture had to hearken back to forms that existed before the rise of capitalism in the 1700s - but strip them of ornamentation to the point that they looked exactly like modern buildings to the untrained eye. They were famous for calling every other style of architecture “immoral”: This was the height of the revolt against Modernism when Wolfe was writing in 1981; I can’t comment on what (no doubt amazing and brilliant) schools have arisen since then. What Should We Make Of All This?Most books on modern art try to convince you that the Emperor’s clothes are splendid and made of the finest silks. I appreciate Wolfe’s commitment to not doing that here. He didn’t give an inch. Still, I would like to read another book by someone equally talented who gives . . . well, exactly one inch. They don’t need to praise modern architecture’s beauty and brilliance - in fact, I would rather they didn’t. I want a book by someone who is overall skeptical, who at least has as a hypothesis “this is all an elite signaling game gone tragically wrong” - but who’s also willing to explain what the modern architects thought they were doing, in their own minds. Wolfe does this only very occasionally, to mock them. He’ll show us a picture of some hideous concrete cube, and say that the architect thought he was “reinventing the idea of light” or something, and that all the other architects praised the building for reinventing the idea of light, and that the architect got a prestigious award for reinventing the idea of light. I would like to read a book by somebody who - while gently holding onto the possibility that it’s all balderdash - tells us what this architect meant by “reinventing the idea of light”, tries their best to help normal people grok it, and comes to a conclusion about whether light has indeed been reinvented. I haven’t found a book like this yet. Everyone either waxes rhapsodic about how amazing the light is, or dismisses the whole thing as trash. Still, I only want this for my own edification. I think we can condemn modern architecture without it. Whether or not there’s some sophisticated perspective from which modern architecture appears brilliant, most people don’t have that perspective. Polls show most people hate it and prefer the old stuff. A quick look at social media will confirm that most people hate it and prefer the old stuff. So who cares whether, if they got twenty years of training in the intricacies of how Venturi is subtly citing Gropius but also subtly undermining him, they would consider it really clever? They’re not going to get those twenty years of training! They have to walk past the building every day! I’m prepared to believe that the great modern buildings have (for example) solved structural support in some elegant and surprising way, or that their minimalist aesthetic does more with a tiny number of elements than people would have thought possible - but these shouldn’t be the most important selection criteria for buildings that shape how people view their communities and their lives. Why should our entire built environment be optimized to amuse a sliver of one percent of the population, even granting that it amuses them very effectively? People mock kitsch art as “the kind of picture you’d put up at the dentist’s office”. But it serves this purpose fine. People don’t want to go to the dentist’s office and see a picture of the Virgin Mary in a vat of urine. You should keep the avant-garde stuff for the museums and let ordinary people living their ordinary life see normal pretty things. So I think it’s fine to hate modern architecture. If someone else says it reinvents the idea of light, just tell them that’s really cool for the 1% of the population who notice it, but that the rest of the world deserves buildings they don’t hate. Wolfe doesn’t chart a path to how things could improve, and lists many obstacles to change. My hope is AI + 3D printing. AI has already ensured that people with no artistic talent can produce the kind of images they want, rather than the kinds that tastemakers say are most tasteful. And it potentially sidesteps the problem of lost expertise. I look forward to a day when people can describe their dream buildings and technology can make it happen. I’ve seen a thousand utopias pictured on the covers of a thousand sci-fi books, and not one of them has been made of unadorned concrete boxes. Until then, I think it’s useful just to call attention to the problem. People are bad at protesting when they think they’re the lone dissenter. If dissent becomes common knowledge, maybe those Selection Committees will go differently. Maybe when the businessmen or the community stakeholders say something, and the prestigious architect sneers at them and says “Oh, so you want it to be picturesque? You love kitsch? Do you go home to your McMansion every night?”, they will draw inspiration from a very wise meme format and answer: 1 Note nominative determinism 2 Ibid You're currently a free subscriber to Astral Codex Ten. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Older messages

Friendly And Hostile Analogies For Taste

Tuesday, December 10, 2024

... ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Indulge Your Internet Addiction By Reading About Internet Addiction

Tuesday, December 10, 2024

... ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Open Thread 359

Tuesday, December 10, 2024

... ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Open Thread 358

Monday, December 2, 2024

... ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Prison And Crime: Much More Than You Wanted To Know

Wednesday, November 27, 2024

... ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

You Might Also Like

STARTING SOON: What do tax cuts for billionaires mean for the rest of us?

Thursday, February 27, 2025

Tonight at 8 PM ET on Zoom: How giveaways for the wealthy are going to hurt everyone else. Tonight at 8 PM ET on Zoom, The Lever and Accountable.US, a nonpartisan organization that tracks and

803408 is your Substack verification code

Thursday, February 27, 2025

Here's your verification code to sign in to Substack: 803408 This code will only be valid for the next 10 minutes. If the code does not work, you can use this login verification link: Verify email

Links For February 2025

Thursday, February 27, 2025

... ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

732866 is your Substack verification code

Thursday, February 27, 2025

Here's your verification code to sign in to Substack: 732866 This code will only be valid for the next 10 minutes. If the code does not work, you can use this login verification link: Verify email

185799 is your Substack verification code

Thursday, February 27, 2025

Here's your verification code to sign in to Substack: 185799 This code will only be valid for the next 10 minutes. If the code does not work, you can use this login verification link: Verify email

Why I never make it to the end of MrBeast videos

Thursday, February 27, 2025

PLUS: Gen Alpha's total immersion in the Creator Economy ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

SEA Airport is raising the roof … literally

Thursday, February 27, 2025

You'll love more elbow room, airfield views, and a bright gathering place GeekWire is pleased to present this special sponsored message to our Pacific NW readers. SEA Airport is elevating your

Go Jeff Yourself

Thursday, February 27, 2025

Darkness Visible, Virus vs Virality ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Zillow’s co-founder has a new idea

Thursday, February 27, 2025

But unlike Zillow, he's opening this company up for investment while it's still private. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

GeekWire 200 CEO survey | Amazon’s entry in the quantum race

Thursday, February 27, 2025

All-woman crew will join Blue Origin's next suborbital spaceflight ADVERTISEMENT GeekWire SPONSOR MESSAGE: SEA Airport Is Moving from Now to WOW!: Take a virtual tour of what's coming.