Alex Danco's Newsletter - Wine tasting with Claude Shannon

Before we start: on April 16th, I’ll be hosting an Interintellect Salon on Thomas Mann’s great novel The Magic Mountain, which is briefly mentioned in this post. I’d love to see you there - you can register for the salon here. There’s some counterintuitive but deep intuition that things can feel higher signal when they are 99% false but 1% true, versus it they are 99% true but 1% false. A grain of truth within a crazy statement can seize our attention more powerfully than a reasonable argument with blemishes here and there. There are many variations of this: like how a tiny pinch of salt brings out more flavour in a dish than a larger dose. Or how the 1% of pro wrestling that’s off-script brings the whole show to life, whereas a football game that’s 1% fixed by refs (but still 99% genuine) would be immediately declared fraudulent. Sometimes homeopathic doses do have stronger effects than conventional ones; at least in the world of information and meaning. I think you should be curious about why this is, if you want to be information-literate in today’s world. You want to be in tune with how powerful that 1% signal is, but also have the presence of mind to not fall for things you shouldn’t. To get to the bottom of this, in this post we’ll spend some time on what exactly information is. We’ll learn it through the kids game of 20 Questions, and the grown up activity of blind tasting wine, to get some intuition around why those grains of truth disproportionately draw our attention. Information is a verb, not a nounA lot of people today don’t know who John Perry Barlow is, which is a cosmic oversight. His life is more interesting than I can summarize here, but as a young man he became the Grateful Dead’s lyricist, and headed up the contingent of Deadheads who helped shape the early internet. He cofounded the Electronic Frontier Foundation in 1990, and his writing is closely associated (and often confused with) Stewart Brand, and with famous lines like “Information wants to be free”. (With the eternal clarification, “free as in speech, not as in beer.”) Buried inside one of Barlow’s essays on digital property rights, there’s a profound paragraph that I’ll copy here in full: Information Is a Verb, Not a Noun. Freed of its containers, information is obviously not a thing. In fact, it is something which happens in the field of interaction between minds or objects or other pieces of information. Gregory Bateson, expanding on the information theory of Claude Shannon, said, "Information is a difference which makes a difference." Thus, information only really exists in the [delta]. The making of that difference is an activity within a relationship. Information is an action which occupies time rather than a state of being which occupies physical space, as is the case with hard goods. It is the pitch, not the baseball, the dance, not the dancer. We’d joke today that “Barlow is a just Bateson wrapper, and Bateson is just a Shannon wrapper”: a lot of roads lead you back to Information Theory. The definition of Information as “a difference that makes a difference” took me years to really understand, even with alternate phrasings like, “Information isn’t what you say, it’s what they hear”. I finally wrapped my head around it after reading Simon DeDeo’s excellent paper Information Theory for Intelligent People. I absolutely love this paper. I find it so clear and intuitive, I find myself rereading it every six months minimum, and I’ll draw from it extensively in the following explanation. “I’m thinking of a person”My older kids have reached the age where we can play Twenty Questions at the dinner table. (We play it very simply: one player thinks of a person, and the others have to guess who from Yes or No questions.) After playing for a little while, you learn that the main way you can “get better” at the game is to know something about the other player and tailor your questions appropriately. You can talk about an optimal strategy for each kid: for our older one, her schoolteachers are a promising lead; for the middle child, try asking about her classmates first. This is the moment where Information Theory enters the picture. I wrote a post a few years ago that walks you through the math (it’s actually pretty approachable) so I won’t repeat it here. All you’ll need is a bit of intuition around probability distributions, which 20 Questions provides for us handily. Let’s do an ultra-simple example: p(Mom) = 0.25, p(Dad) = .25, p(Big sister) = .25, p(Little sister) = .25. You can quickly work out that this distribution, P(x), takes exactly two Yes/No questions to solve. Now let’s suppose Dad’s ineligible, and Mom’s twice as likely. So we have a new distribution Q(x): q(Mom) = .5, q(Big sister) = .25, q(Little sister) = .25. You should intuit that this should take less than two Yes/No questions on average, because if you guess “is it Mom” right off the bat, half the time you’d be right. Shannon’s equation lets us calculate, from known probabilities of Q(x), that our average question tree length will be 1.5. Once that’s comfortable, let’s go ahead and play a real game. (We’ll reuse our P and Q variables.) For child one and two, we’ll define distributions P(x) and Q(x): the set of people that they routinely select for you to guess, and the relative likelihood of each. We can say a few things about these distributions:

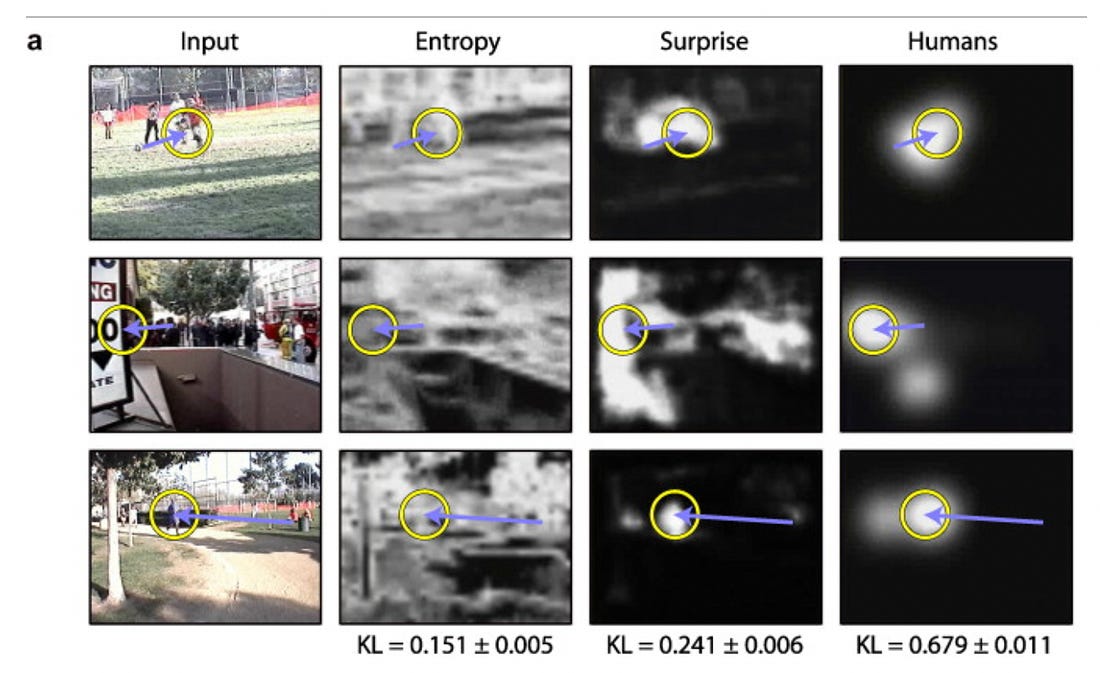

Why does this work? As the guesser, the fact that we know something about her map of the world - how big it is and how it’s coded - means our guessing process can take fewer questions on average. It has less uncertainty to resolve. That quantity of “uncertainty-to-resolve” is called H(X), or Entropy. It is not an absolute quantity, it is a Delta; and it’s measured in Bits. This is very much in the same world of Bayesian probabilities, and managing priories; but I find the Shannon lens gives an important emphasis on “Uncertainty-to-resolve” so we’ll keep going with it. Surprise!Now, let’s imagine we’re playing the game with a blindfold on, and you don’t know which kid you’re playing against. Pay close attention here because this is the critical step for understanding what Barlow and Bateson are getting at with “Information is a verb, not a noun.” So in this blindfolded version, we don’t know if we’re interrogating P(x) or Q(x); but we must commit to a questioning strategy at the outset. So let’s say we choose a questioning strategy that’s optimized for the older kid’s probably distribution P(x), but then over the course of our questioning we discover that, actually, we’ve got the younger kid. Rats! We were inefficient with our question tree. We can talk about the additional work we must do of asking questions when we were expecting one distribution, P(x), but actually encounter another one, Q(x). Note carefully that these additionally incurred questions are not because the distributions are contain different amounts of latent uncertainty. It’s because our questioning itself had been non-optimal, and now has to be recalibrated. That additional uncertainty has a formal name, “Kullbach-Leibler Divergence”. And it measures the extra uncertainty, in bits, that we incur in the discovery that we are dealing with a different distribution than we expected, and it’s a signal to focus our effort in a new place. The everyday name for this is “Surprise.” These moments of surprise are when we actually learn things. It’s the moment when you realize that your map of the world - your internal model of the current situation - does not actually match the facts on the ground, and we need to switch up our map. Whatever answer surprised us with, “this is actually Kid 1, not Kid 2”, was a difference that made a difference. To spell it out: it was a difference in observed versus expected values, that makes a difference in our selection of coding tree, which can be measured in bits of newly appreciated possibility associated with the new uncertainty. I’ve written about this before, in a post called The Audio Revolution. The relevant part was about feed-forward information processing, and how most of the time, the world we perceive is actually a pre-populated model of objects and spaces from our working memory, which we then “error-check” against a low-bandwidth sample of real sensory information. When you’re in a familiar environment, like your living room in your house, you draw on a richly defined, pre-populated environment of what everything in the picture is (call it P(x), and a well-rehearsed strategy for what “questions” you ask of the world. But if you walk into your house and something is amiss - say, the TV is missing - that is a difference that made a difference in what your model of what’s going on, and what questions you now ask of the world in order to figure out what’s going on. This is why it’s actually incorrect to say “They said something surprising.” They just answered the question. What actually happened is you HEARD something surprising. That’s what information really is. Information is not the baseball (the kid’s answer), it’s the pitch (the impact of the answer on the model that was perceiving it.) It’s not the dancer, it’s the dance. From Itti & Baldi, 2009: Vision Research As it turns out, our brains are optimized to care about surprise, and we can measure this scientifically. You can show someone a movie and calculate, for each pixel on the screen, how much uncertainty there is in each pixel over a time series. And you might think “our eyes are probably drawn to the pixels where there is uncertainty”, but that’s not what happens. Maximal uncertainty is actually like the “snow” pattern on an old TV - it’s not visually interesting. What our eyes are actually drawn towards is, guess what, KL Divergence. Our eyes follow the pixels that are surprising. Because that’s where the information is! In our 20 Questions game, these areas of “surprise” where our eyes are drawn are analogous to whatever bit of information makes us realize, “We have the younger kid, not the older kid.” That little bit of information is probably a small thing, but it’s a small thing that makes all the difference. And that’s where our attention is drawn. Although Twenty Questions is a great starter example, it’s not very realistic. In real situations, we don’t always get to directly interrogate the Ding an Sich (Kant’s Thing In Itself); we’re dealing with interpretations, representations, unreliable signals, and noisy channels, from which we have to extract and recreate a signal. (The one way in which 20 Questions with kids is realistic is that they are not totally reliable narrators! Their models of the world sometimes differ from ours, and knowing which answers to trust is part of the meta-game.) Freshly Cut Garden HoseAs it happens, several friends and I have recently gotten into a more grownup version of 20 Questions: blind tasting wine. It adds the dimension of noisy, unreliable signals, and even better illustrates KL Divergence and Surprise. Blind tasting wine is a fun challenge, and can be absolutely humiliating. It’s a lot like investing - it’s easy to find yourself on a hot streak and think you’re smart, but very hard to actually be skilled at it. But you can work at it and get better. We talk about “training your palate”, and a lot of it is learning to recognize discrete smells and tastes, but it’s just as much a mental training exercise for the general skill of how to sift through and resolve uncertainty.  In moves like Somm, or other romantic representations of wine tasting, you get an impression that candidates are solving an elaborate 20-dimensional puzzle:

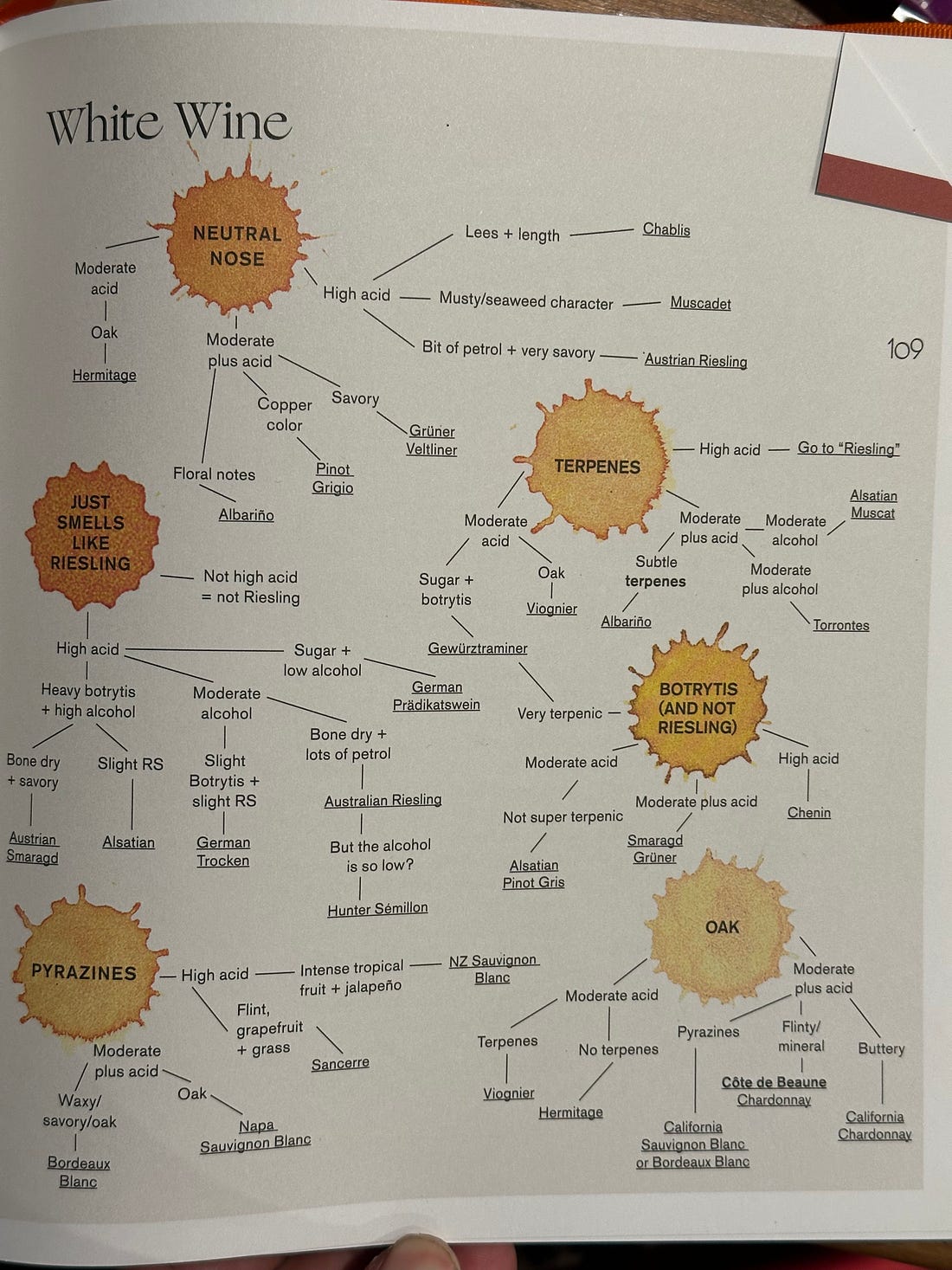

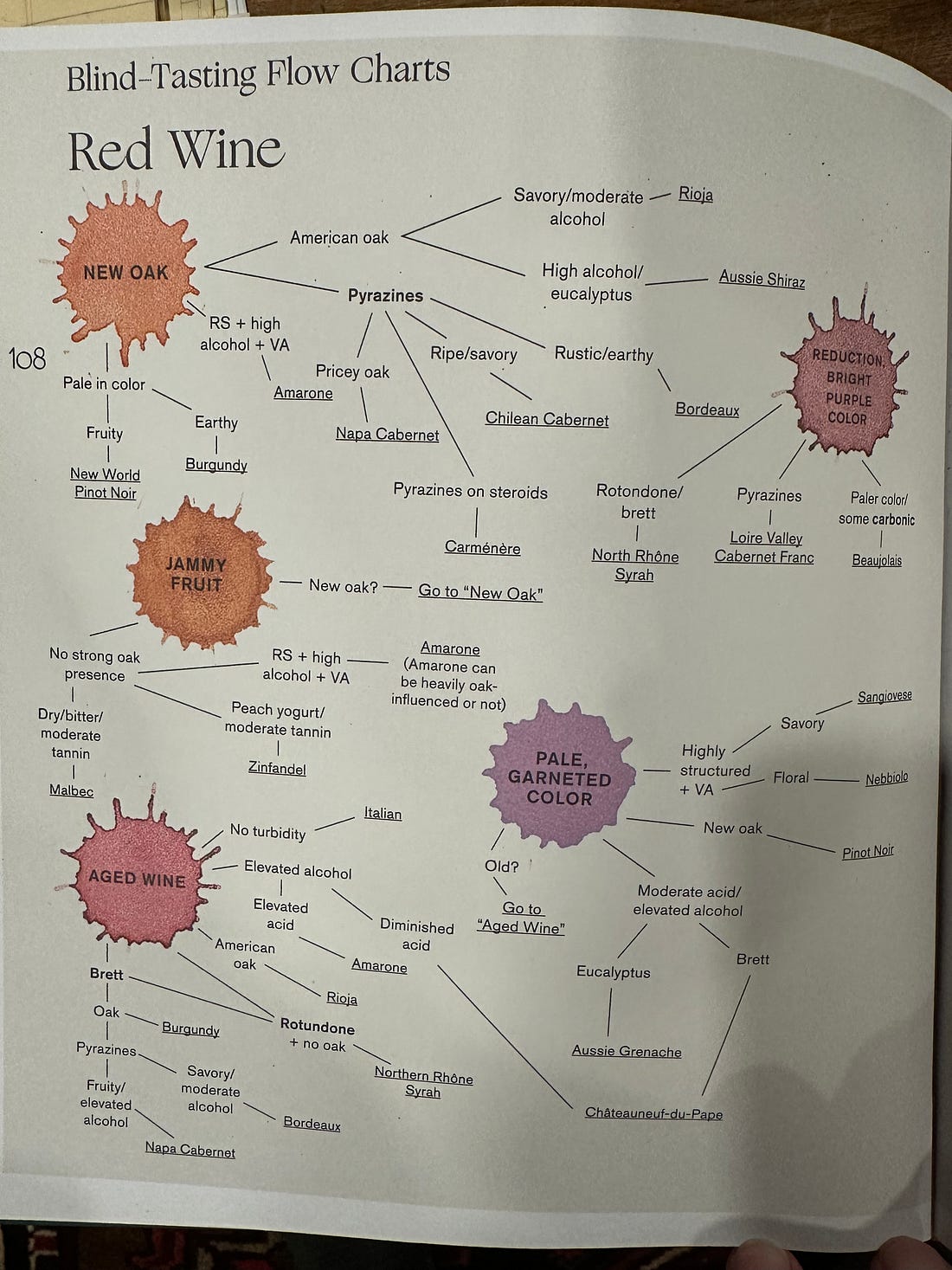

As fun as these “grid tasting” portrayals are, they make it look easier than it is. (It’s a bit like watching poker on TV, when you can see the cards.) In practice, you’re not dealing with clear signals: you’re dealing with broad correlations and faint hints. Any one data point (“raspberry fruit”) could point you in many different directions. Moreover, you aren’t always so sure you’re really tasting something, confusing it for something else, or just imagining it. Taste is notoriously adaptive to the power of suggestion. (Curiously, the one sense I find people chronically under-use is their eyesight - how the wine looks will not fool you, at least not nearly to the same degree as what you think it tastes like from minute to minute.) Wine can be tasted “double blind”, where you know nothing about it at all, or “single blind”, where you know some information (e.g. what grape, or what region) and you have to figure out the rest of its characteristics. The standard things you’re trying to figure out are, what grape(s), what region, what year, and if you’re particularly ambitious, what producer. While Double Blind tasting looks more impressive, it’s generally thought that Single Blind is the more valuable exercise for learning how to taste - you aren’t floundering around in the dark; you can actually control for some variables while you interrogate others. Jensen-Shannon DistanceSo, when we think back to what we learned in 20 Questions, wine tasting is the same idea: particularly the concept of KL Divergence and “Surprise”. Wine tasting is all about pulling out maps of what you think the wine might be (P(x)), while remaining alert to signals that don’t fit (and suggest you’re looking at Q(x)). The temptation, particularly for new tasters, is to approach the wines inductively. Let’s do an example! You try a red wine; it’s solidly built with grippy tannins, and old world oaky tobacco-leather taste. Then, like a laser beam, you pick up cassis: black currant fruit. Your mind immediately goes to Bordeaux. Yep, that’s delicious. You try to focus on where in Bordeaux this could be - left vs right bank. Black currant suggests cab; it really reminds you of a Margaux you had last month, so let’s guess that. The wine is revealed, and it’s not Bordeaux at all. It’s from Rioja, in Spain. Where did your line of questioning go wrong? You can retrace your errors. You were initially on a good path with the oak, tobacco, leather, and black fruit. But that little signal of “cassis” drew away all of your attention, and made you pull out the Bordeaux map. And once you were reading from the Bordeaux map, you missed some pretty big clues. First, the wine has a screaming taste of dill pickle, which should tell you American oak, and therefore you’re in Spain not France. Second, there’s no trace of green pepper or other pyrazine taste, which doesn’t strictly rule out Bordeaux, but certainly suggests you consider alternatives. And third, tasting it again, that isn’t really black currant, is it. It’s more like black plum. Close, but not the cabernet signal you’d initially thought it was. (If you like these tasting note differential sheets, they’re from the excellent book Vignette, by Jane Lopes) The moment you picked up that cassis signal, you were “Surprised” in a particular direction. You interpret it as “Get out the Bordeaux map, that’s the distribution we should be working off.” And then in asking questions about P(x), you got some fuzzy answers that suggested one place or other. But we were wrong about the wine, and we were using the wrong map. The KL Divergence of Tobacco overwhelmed our ability to look around the rest of the picture. We were surprised by one thing, and it blinded us from being surprised by other things. The failure is that you immediately got into a headspace of “I recognize this.” Inductive reasoning is dangerous, because you’re telling yourself a story about what your senses are telling you, and then you spend all of your energy focusing on that story. So you may miss some big obvious hints. What we are supposed to do when we blind taste is to resist this temptation to leap to a hypothesis. The right way is to approach it deductively. You look, smell, and taste the wine, and just try and describe it as non-judgementally as possible, gathering information. Then, based on all of your observations, you use logic and theory to rule things out: “What can this wine not be?” Is going to fool you much less of the time than “What do I think it is?”, because you’re not latching onto an inductive hunch. As you do that for a while, you build up for a theoretical case for what this wine is all about - the weather, the winemaking, possible grapes, possible terroirs. Only then are you allowed to float some hypotheses for what the wine is. Similar to KL Divergence, another term you can take home from this post is “Jensen-Shannon Distance”, which describes how much information you get about the distributions (P(x) vs Q(x); or, “typical Bordeaux vs typical Rioja”) you get from each question you ask, like “Is there any pyrazine?”. The units of JSD, once again, are in bits - how much information you get about the final answer once you know the identity of the “player” (which could mean the grape, the region, or whatever taste profile is in your mind.) For more on JSD (including the important topic of “mutual information”, which I didn’t get to cover here, read the DeDeo paper.) That’s not to say that a deductive approach leaves you completely invulnerable to false trails. But by analytically working through a grid of characteristics and working through what the wine isn’t, sooner or later you’d encounter signals like “No green pepper” and “Yes dill pickle”, both of which are signals that you are not dealing with distribution P(x), you might be dealing with a different Q(x). And the earlier you can catch these big signals, the more likely you are to see them at all. Because once you get blinders on and you’re going down the path of “Cassis!!”, all of the other signals are just going to get force-fit into your reading of P(x) and you’ll miss what’s actually going on. It’s never LupusThere’s a line in medicine, “If you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras” that’s used to illustrate Baysean probabilities. Learning how to appropriately weigh prior probabilities is an important part of learning how to think well. (The classic Bayesian intro question is: “Alice is a quiet person who loves organizing and doesn’t like to be rushed. Do you think Alice is more likely to be a barista or a librarian?” And the right answer is barista, simply because there are many more baristas than librarians out there, and the special information you gained about Jane is small relative to the employment prior.) What I hope you’ve gotten an appreciation for here it that tiny bits of information, assembled amidst otherwise broad and predictable distributions, have a powerful effect on where we focus our attention. A great example from TV is in House, when tiny details throw him down paths of being absolutely certain he finally has a case of Lupus, but it never is. Now you have a better sense of what’s going on: that one tiny detail that stood out to you seizes a disproportionate amount of your attention, because it tells you “New KL Divergence just dropped, you have work to do”. You then pull out a new map (a new question strategy, in 20 Questions; a new grape or region hypothesis in wine tasting) and from there on, the main thing that matters is interpretation of that new hypothesis. From the little black currant clue that sent us into Bordeaux territory, we then found all kinds of signals took us to Margaux as opposed to St Julien or whatever, even though the broader data set did not actually support Bordeaux all that much. It reminds me a lot of the book The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann, where the intellectual spine of the book is an ongoing dialectic between two Italians. One of them is a bourgeois named Settembrini who’s comical, but basically sensible in what he advocates. The other guy, a character named Naptha, is a Jesuit communist warmonger with crazy arguments (among other things, at one point he argues forcefully that heliocentricity is just a passing fad), but with undeniable little grains of truth sprinkled in that are unbelievably compelling, and kind of right. Reading the book, you get fixated on those grains of truth and a whole world of legitimacy gets constructed around them - even if most of his raw content is insane. You can’t help but be fascinated by him, and he somehow wins every argument. He reminds me of RFK a little bit. It is hard for us to resist these grains of signal, because they are what signal IS. And it’s equally hard for us to step back and sort through what else we’re perceiving, because they’re not signal, unless we really train ourselves to set aside our inductive instinct. What you can do is remember Bateson’s definition of information: a difference that makes a difference. Information is a change in uncertainty-to-be-resolved, and it happens to the receiver. If you’ve made it this far: thanks for reading! I’m back writing here for a limited time, while on parental leave from Shopify. For email updates you can subscribe here on Substack, or find an archived copy on alexdanco.com. |

Older messages

10 Predictions for the 2020s: Midterm report card

Thursday, February 27, 2025

In December of 2019, which feels like quite a lifetime ago, I posted ten predictions about themes I thought would be important in the 2020s. In the immediate weeks after I wrote this post, it started

Innovation takes magic, and that magic is gift culture

Thursday, February 27, 2025

Silicon Valley's great trick: recasting well-worn business procedures as moments of gift exchange ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Tokengated Commerce

Monday, May 2, 2022

A very special issue with Packy McCormick & Not Boring

Games

Sunday, November 7, 2021

Alex Danco's Newsletter, Season 3 Episode 22

Twist Biosciences: The DNA API

Sunday, September 26, 2021

Alex Danco's Newsletter, Season 3 Episode 20

You Might Also Like

3-2-1: On the power of inputs, how to build a creative career, and the one habit that matters most

Thursday, March 6, 2025

“The most wisdom per word of any newsletter on the web.” 3-2-1: On the power of inputs, what holds quiet power over you, and the one habit that matters most read on JAMESCLEAR.COM | MARCH 6, 2025

In the midst of stagnation | #129

Thursday, March 6, 2025

It is time to go backwards before it is too late ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

The Jigsaw Puzzles Worth Their Weight in Gold?

Thursday, March 6, 2025

OK, not quite -- but it's close!

🧙♂️ 10 Brands Paying Creators NOW (March 2025)

Thursday, March 6, 2025

Plus secret research on Room & Board, Blue Apron, and Columbia Sportswear ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

AI in Agile Product Teams

Thursday, March 6, 2025

Useful Insights from Test-Driving Deep Research ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

For Authors <•> Book of the Day Promo <•> Email Newsletter • Facebook Groups posts

Thursday, March 6, 2025

Reserve your date... "ContentMo is at the top of my promotions list because I always see a spike in sales when I run one of their promotions. The cherry on my happy sundae with them is that their

🌅 Welcome to Creative Joy Beams

Wednesday, March 5, 2025

A mini joy manifesto to celebrate that Creative Wellness Letters is becoming Creative Joy Beams! 🎉 ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

How to integrate Stripe's acquisition of Index? (2018) @ Irrational Exuberance

Wednesday, March 5, 2025

Hi folks, This is the weekly digest for my blog, Irrational Exuberance. Reach out with thoughts on Twitter at @lethain, or reply to this email. Posts from this week: - How to integrate Stripe's

The Man With the Golden Arm

Wednesday, March 5, 2025

How to save millions of lives without even going anywhere (but you need the right blood)