After Torrey Peters published her debut novel, Detransition, Baby, in 2021, her life changed dramatically. Though she’d been writing steadily for ten years, this was her first commercial success, and it was celebrated in a way that few first novels are. The New York Times put it on its list of 100 best books of the 21st century. The TV rights were bought by Amazon. It’s fair to say that, for many of its readers, the novel gave them their first experience of a world populated by openly trans characters. Without having intended to do so, Peters became a spokesperson for trans women. It wasn’t easy for her to figure out what to do next.

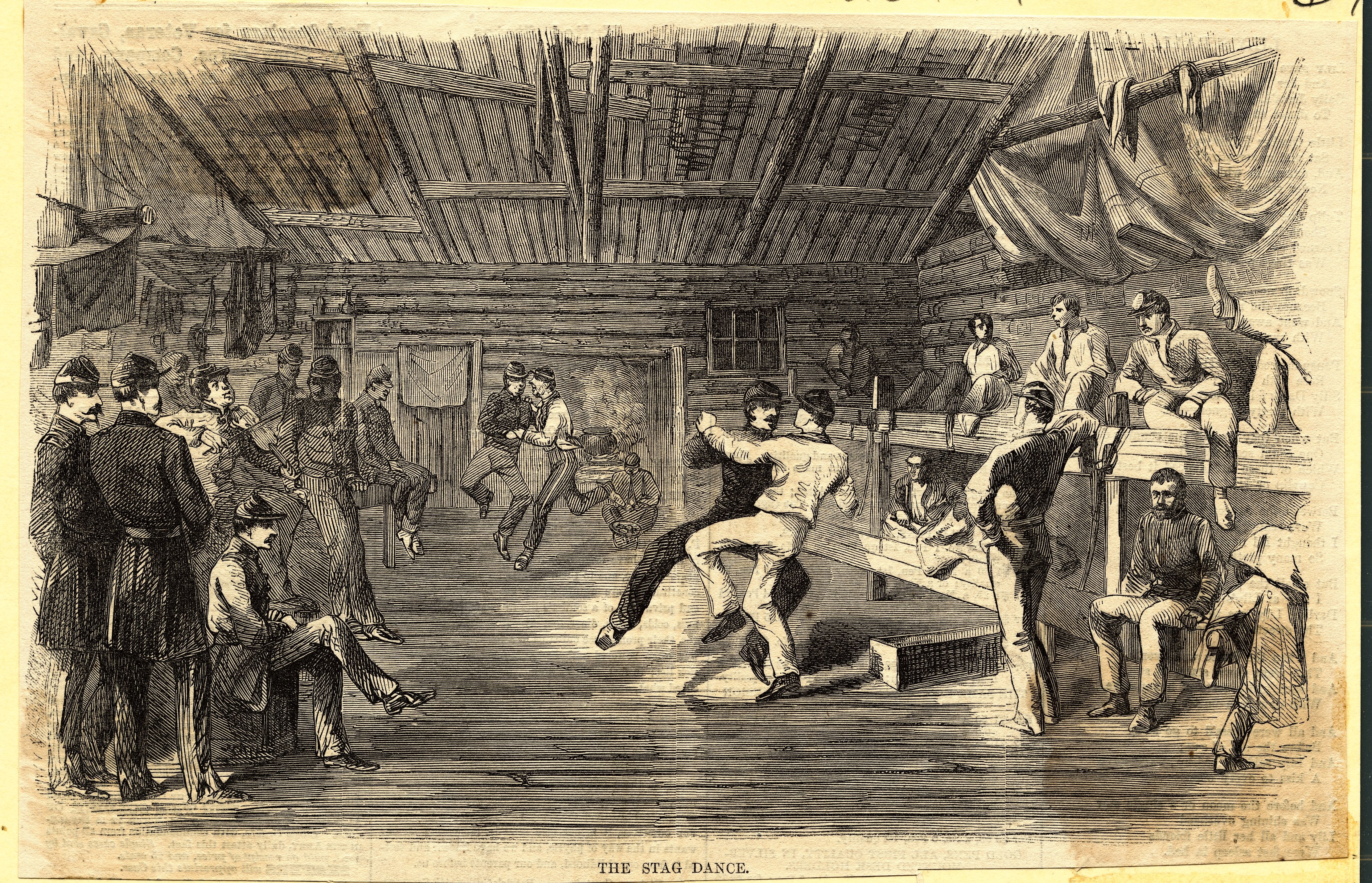

In “Stag Dance,” the title novella in a collection published last week, Peters took a huge conceptual leap. She wrote about an illegal logger camp in frontier times, where characters speak in sometimes impenetrable slang. The narrator, a plug-ugly behemoth his fellows call “the Babe,” after Paul Bunyan’s blue ox, wants more than anything to be accepted as a woman in the context of the camp’s stag dance, an event in which men who wish to be courted as women wear inverted brown triangles of fabric at their crotches — a phenomenon based in historical fact. “It’s so vulgar and on the nose that if I had come up with it myself, I'd be like, I can’t do it,” Peters told me. The Babe isn’t immediately accepted as a woman, but the camp “punk,” a pretty boy named Lisen, is, leading to a sisterly rivalry that doesn’t end well for anyone. In “Stag Dance,” Peters has created an indelible narrator with a highly specific point of view, as well as a moving, immersive world. Here, she explains how and why she did it, and tells us what’s going on with TV adaptations of her work (a meeting with Taylor Swift’s manager was involved).

Emily Gould: The three stories and the novella in this collection were all written in different genres, ranging from speculative fiction to horror to teen romance to western/tall tale. What appeals to you about playing with genre?

Torrey Peters: When I first conceived of these stories, around 2016, a lot of trans writing was very sure that it had to be a specific thing: In order to capture the trans experience, we have to invent a totally new narrative for this wild and different style of life that has strange punctuation and asterisks and parentheses in it! And I was very resistant to this because I was like, I actually think that trans lives are built out of the exact same things that any other life is built out of. The emotions that are operative for a trans person are the exact same emotions that are operative for anybody else. It may be arranged slightly differently or with slightly different balances, but 99 percent of them are all the same. And so, there was a way in which I was like, You know what? I'm going to just write trans stories to show that you don't need to invent some othering form to explain a trans life. You can explain a trans life in a teen romance. Then, I just started finding them fun.

Emily: What was the genesis of “Stag Dance,” the title novella?

Torrey: Well, I think it was a very perverse thing for me to write. I think if you were like, What would readers of Detransition Baby like to read?, nobody was like, We want to read about loggers putting on a dance in winter. Nobody wanted it.

I was totally overwhelmed by Detransition, Baby, by talking about Detransition, Baby, by being so positioned as representative of trans literature, by the surprising places that Detransition, Baby showed up. I really felt like, I don't know how I'm speaking to this audience. And that was very paralyzing in some ways.

Basically I was like, Nobody wants a lumberjack dance written in period slang, and because of that, I’m actually totally free to do whatever I want and try whatever I want and do things in my writing that I've never done before. Whereas, when I was writing things that were closer to what I’d done before, I kept getting stuck. When I discovered, Oh, I get to write this, I felt this real sense of play and I was amusing myself every single day as I was writing it, which was not happening with the other stuff I was trying to do.

Then slowly, as I was figuring out what it was, which it took me like a year and a half to do, before almost everything else, I found the cadence or the voice of this character.

Emily: How did you learn about the stag dances?

Torrey: There’s a book called Re-Dressing America's Frontier Past, by Peter Boag. It’s a queer reapproaching of the frontier, like: Look, obviously this was a bunch of men all out in the woods. Whether they're at railroad camps, whether they're at logger camps, whether they’re soldiers — they were all lonely, they were all probably horny, and they actually had all sorts of customs that they did with each other to assuage that and to feel good.

I learned that these frontiersmen and soldiers would literally have these winter dances, and to designate yourself as a woman, you would cut out a brown triangle and hang it upside down over your crotch, like a bush. It’s so vulgar and on the nose that if I had come up with it myself, I'd be like, I can't do it. But the fact that I have a historical precedent for it was like, Well, I'm not going to pass this up. It seemed so on the nose because an upside-down triangle is the symbol of homosexuality in the 20th century. This symbol is so potent. The term “stag dance” was also a historical term. The Civil War soldiers would put on stag dances.

It seems totally intuitive to me that if a bunch of men are together, femininity is going to find its way into that world. I’ve already received a few messages from people who read the book and were like, Yeah, my grandfather describes stuff like this.

Emily: What kind of research did you need to do in order to write the period slang accurately?

Torrey: I discovered this dictionary of logger slang called Lumberjack Lingo. The children of loggers collected the slang of their parents. And I started making a glossary of which slang and which words I liked and wanted to use, and I added that into this cadence that I had found. Eventually I started finding that not only did I feel free to write because there weren't any expectations around writing in this way, but I also found that the language and the style kind of freed me to talk about gender differently.

“Punk” for a young boy, that was logger language, which then in the Depression became tramp language because all of these older working men became tramps, unhoused men who rode the rails, during the Depression. Then because they were poor, they were constantly getting arrested and thrown in prison. So now the prison slang for the relationships that men have in prison with each other, they still use words like “punk.” It goes back to the logger stuff.

I was on tour for Detransition, Baby, talking about gender all the time, and the words had become kind of calcified in my head. A phrase like “gender dysphoria” is like granite to me now. I just can't enter it. There's nothing there in that phrase for me. Re-approaching some of the things that I thought I had been talking about in language that was completely unfamiliar to me and that didn't actually lend itself to that kind of discussion reanimated the discussion for me and made it fun and surprising, even for me. I thought, I know how I would say it, but I don't know how to say it in this vernacular.

Emily: So in the logging camp, situational homosexuality is pretty much tacitly accepted as inevitable, but actual homosexuality is still strongly taboo. Then whatever the Babe is, as the Babe gradually understands or realizes, is so much worse than taboo that it's unspeakable. There's this idea that's both right out there in the open as long as it's a joke, but if it's not a joke, it's deadly. When did the broad outline of how you were going to dramatize that come to you?

Torrey: It’s been in my own life, by analogy. The party line in trans politics is that if you want to transition, you can. You just say, Well, I'm a woman and everybody should respect it, then you've done it. And it is important that we give everyone access to declare what they want to be. But when I look at how people actually live, it doesn't work that way.

We all get a body, then we say how we want that body to be interpreted by the world, and it's a negotiation. It's especially true for trans people, but it happens to everybody. A man could be like, I'm an ultramasculine, rugged guy. And someone could be like, “Well, you're four inches too short for that.” And it's not fair because the guy who's six-foot-six, he gets to do it even though he might not be as good at it.

One of the things that is very uncomfortable to talk about with other trans women is that not everybody's transition is the same amount of easy, or is even the same path. It's not the same. It's not, Okay, you said you're a girl and I said I'm a girl and we'll do the same five steps and end up in the same place. There's all sorts of things, like what kind of body you get, how much money you have, what kind of childhood you had, all these things that are kind of arbitrary, but they add up to make for totally different transitions with totally different levels of ease. And that creates all sorts of different levels of resentment.

That, to me, was the real center of the story. The Lisen character has to do almost no negotiation with the world. Everybody's so eager to give Lisen female pronouns in this story, so eager to dance with Lisen, so eager to have Lisen gratify them.

After the Babe declares himself a woman, nobody accepts that. When you declare yourself a woman and nobody accepts it, there's a potential to become something else and be treated as something else. This feels very politically dangerous in an intra-trans kind of way. I'm not trying to hurt anybody's feelings about how they look and feel. But I wanted to write a story that gets into it. And asking these questions in such a defamiliarized place where it's kind of this ridiculous, funny logger character, it means maybe I can actually talk about this stuff that I think I've experienced from both sides.

Emily: I wanted to talk about the Babe and Lisen. Lisen is a pretty boy, the camp punk, a familiar figure to his fellows. He's pretty, flirts, he draws people in. Early on, we learn that he is rumored to be having sex with the boss. But then there's this uneasy truce that forms between him and the Babe leading up to the dance. That truce has seeds of distrust implanted in it from the beginning. And they talk about sisterhood. What does sisterhood mean in this context?

Torrey: Detransition, Baby was about motherhood, but I've been thinking much more about sisterhood of late. Because I think sisterhood is where you recognize that you love this person and that you're connected to this person, that this is the person whom you should be with through thick and thin. And yet also, sisterhood is the place in which you're actually, within a family, competing for scant resources. You're competing for your parents' attention. It's the person who knows you well, and knows where you come from, and so can actually be truly cruel to you in an intimate way. Not brutal to you. A stranger can be brutal to you. But a sister can be cruel to you because she knows you, and it's intimate.

When the Babe decides that he wants Daglish, their boss, it’s not because he’s attracted to Daglish. What he's attracted to is that Lisen has Daglish. His desires for Daglish are not even really about Daglish. They're about being the kind of sister that Lisen is, being the kind of woman that Lisen is.

I see that kind of thing happening all the time with trans women. Because I've been around so many trans women and I've known so many trans women and had so many different types of relationships with trans women, we're almost painfully naked to each other. I can see a trans girl's style and be like, Oh, you're trying to emphasize this about yourself and minimize that about yourself. To see it that way, it's a kind of intimate kin thing. And yet also that means that I can hurt that person, or that person can hurt me by being like, All your attempts are incredibly transparent. The capacity for cruelty is so expanded in that way, and also just the way the world is. Sisterhood is throughout this entire book as a way of thinking about and understanding both the love for other trans women that I have but also what's difficult. Maybe it’s even about what happens when you grow up. Do you want to spend all your time with your sister? I don't know. Some people do. Maybe not everybody though.

Emily: Without giving away the ending, I wanted to talk about where you wanted to leave your hero at the end of the story. Because we've gone on this journey and it's ended in a very unexpected place.

Torrey: As I was writing this, the actual ending was going to be this totally different ending. It was going to be this whole jail scene that I had envisioned. Then I suddenly was like, It's the Big Dance. This is just the Big Dance movie. It's 10 Things I Hate About You. It's Carrie. But why does the ending of Carrie feel satisfying? The ending of Carrie is that it suddenly gets supernatural and quite extreme in ways that were just hinted at before. And I was like, Well, what if I just fully turned it into that at the end? What happens when you tell everybody that you're a thing and nobody accepts you as that thing. It's not like you go back to being the thing you were before; it's that you become something else.

For me, the ending was a literalization of what happens when your gambit to become a new person gets rejected. When the gambit's rejected, you become a monster.

Emily: What’s going on with the Detransition, Baby TV show?

Torrey: The TV show's dead. It's sadly dead.

Emily: I hope you got a lot of money, at least.

Torrey: Yeah, I got paid. Hence my winters in Colombia. But Amazon streaming … This is my fault. I decided to go to Amazon. I had two offers. I had one at FX and one at Amazon, and I chose Amazon. And I don't even think it had anything to do with my show. At a certain point, Amazon fired all its executives and got rid of 95 percent of the shows that it had in development, including by people who I think are so funny and more talented in TV than me.

This is just what everybody kind of says happens to writers who go to Hollywood. You get really excited. Everybody says, “We're going to do this. We're going to do this.” And then one day it's all over.

I'll tell you a funny story, which was that I wrote the pilot with a spot for Taylor Swift in it, which was not meant to be Taylor Swift. She was a stand-in for any recognizable cis actress who would play a dysphoric projection of Ames. Then I got a message from the producers: “Okay, well, now we need you to go get Taylor Swift.” There's even a note in the back of the script like, “We're not really going to get Taylor Swift.” I literally chose Taylor Swift because her initials are T.S. and it was funny to have T.S., which is the old abbreviation of a transsexual.

And so my producer somehow heroically got a meeting with Taylor Swift's music manager, which was the most humiliating meeting that you can possibly imagine. It was literally like, “Hi, we're about to go on a $1 billion tour, what is it that you want from us?” And I was like, “We'd like you to play the dysphoric projection of a trans woman in three episodes of an Amazon show that's not about to get made.” I mean, they were nice to us, but it was so humiliating to do this and to be told by the producers, "This is the last-ditch effort," that your show's not going to get made unless you can get the thing that you wrote as a joke.

I was obviously really sad because I believed a lot of the things that people were saying, then it was suddenly over. And it took a couple of months to kind of be like, What? It all just went away. That's so weird. And now I just feel totally relieved, actually.

Emily: Are you working on another novel?

Torrey: The weird thing about the past month, with politics, is that people flee to allegory and historical fiction in these situations. But I've already done those things in this collection, so I feel like I need to take on what's actually happening. A real story the same way I did with Detransition, Baby, probably third person, free indirect narrator, which I didn't do in any of these stories. Just classic literary fiction about now. What is a way that I could set up a story that is flexible enough to still work if everything goes to shit with both the country or trans rights, and also is not just some “two steps ahead of a dystopia” story? That’s something I've been trying to figure out. What is a way to write about this moment that isn't pegged to the news?