Our laptops wouldn’t look quite the same without this invention. (Melissa Keizer/Unsplash)

The guy who turned a $100 loan from his fiancé into an adhesive giant … after a name change

These days, as people are stuck at home trying to get some dang work done, many of those folks have stickers on the back of their laptops. Some of them are quite creative and clever; many of them never get removed, of course.

(I thought the design of my HP Spectre x360 was simply too lovely to add any stickers to, but on my MacBook Pro, I have the warning label commonly seen on the back of NES games—you know the one, the one that warns not to immerse the game in water.)

In many ways, the roots of how we got all these stickers on our laptops comes down to a guy named Ray Stanton Avery. Avery was known as a tinkerer while a student at Ponoma College, and had a great interest in a printing press that his father, a minister, used to print sermons and church bulletins.

According to his entry in Oxford University’s American National Biography Avery had experimented with ideas such as a phonograph with a built-in alarm clock, which led to a role with an on-campus firm that produced its own primitive self-adhesive labels. Avery was brought in to improve the machinery used to create those labels. (One technique he used involved a cigar box with holes cut out of it to allow for the application of adhesive to the back of a sheet of paper.)

The company failed, but he kept experimenting with the ideas, thanks to $100 in seed money he received from from Dorothy Durfee, a schoolteacher who later became his wife. (His second wife, apparently, as when I was researching this I found an article suggesting he was married once before—something not mentioned in prior biographies!)

Avery’s goal was to come up with an easier way for stores to price products, by putting easy-to-remove labels on the objects.

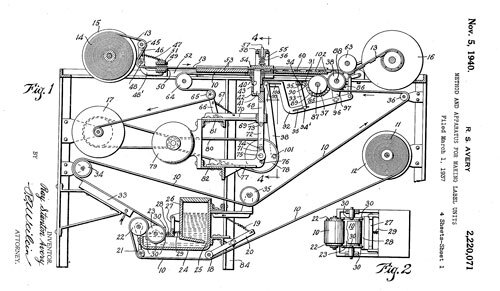

The self-adhesive machine invented by Avery. (Google Patents)

Combining various cast-off parts, including a motor from a washing machine and a saber saw, Avery managed to build a method for labels that were both self-adhesive and die-cut, making them both more efficient and easier to use than other types of labels common at the time.

In his 1937 patent filing explaining the benefit of the approach:

In order to provide labels which can readily be affixed to all kinds of surfaces, and yet be easily removed without leaving marks or otherwise damaging said surfaces, the present invention contemplates the application of a pressure sensitive adhesive surface on the labels. Such adhesive surfaces are characterized by the fact that they do not require moistening prior to their application, but are affixed to a surface by slight application of pressure, and are readily removable by peeling from engagement with the surface to which they are adhesively affixed.

The name that Avery chose for his company that created this obviously quite important line of labels? Kum Kleen Products. (He was an inventor, not a branding expert!)

Did they not have any self-awareness in the 1930s? (via Avery Denison)

Fortunately, Avery had the good sense to change the name to Avery Adhesives, a firm that revolutionized labeling over the next 50 years, gaining use in things as varied as stickers, postage stamps, product labels, and numerous other things. By being able to apply pressure to affix a label rather than by moistening the surface as one might do with a vintage stamp, it made the adhesives easier to manage and more foolproof.

Avery’s namesake company, now known as the adhesive manufacturing company Avery Dennison, has been around for decades, mostly focused on packaging, retail labeling, and industrial use cases. But you probably know the Avery name because of the fact that the company moved into office-supply products, mostly adhesives, starting in the 1980s.

These labels took advantage of the fact that printers were becoming increasingly common both in the office and the home, and were often printable. One common use case for the labels was to print addresses where you were going to send, say, invitations. It took half a century, but Avery’s bold idea found a perfect use case in the 1980s.

You can probably credit Ray Stanton Avery for the rise of the “Hello my name is …” badge.

Avery Products Corporation, the label-making subsidiary, was eventually sold off from Avery Denison, but is still active today, producing labels that you put on letters, perhaps, or on boxes, or on floppy disks. (Maybe even CD-ROMs? More on that in a second.) They, along with competitors such as 3M, were fairly ubiquitous throughout the 1980s and 1990s, only falling out of favor to a degree because of the fact that we rely on computers to label things now, no printer required.

These days, the company offers custom-printing services for those who want something nicer than a mere inkjet printer can produce.