This is the once-a-week free edition of The Diff, the newsletter about inflections in finance and technology. The free edition goes out to 8,866 subscribers, up 636 week-over-week. This week’s subscribers-only posts:

The 1.5th Wave: The Worst of Both Worlds: this post highlights the US’s combination of a) widespread indifference to the virus in some places, which causes it to spread, and b) widespread fears about the virus elsewhere, which keeps economic activity low for as long as the virus is spreading. It’s a bad combination.

China’s Other Virus Crisis explores the effects of African Swine Fever, which may have wiped out half of China’s pigs, putting the world’s biggest pork consumer in a difficult position. Credit to Matt Prusak for suggesting that I look into this a while back.

Reserve Currencies as Giffen Goods and the Consumer of Last Resort looks at the peculiar economics of the dollar’s reserve currency status at a time when the US economy isn’t doing well. Many Americans will suffer if the next stimulus package is small or delayed, but the biggest impact could be felt elsewhere.

The Hack: When Crime Pays Fractions of a Penny on the Dollar is a look at the microeconomics of hacking into Twitter and using it to steal $100,000 worth of Bitcoin instead of crashing a market or starting a world war. I, for one, am happy that this was the outcome. And I don’t think it’s surprising, either.

In this issue:

SPACs as a Call Option on Hype

More on the Twitter Hack

Corruption, Liquor, and the China Bubble

Q/Q^44 != Y/Y

Wolf Warrior Diplomats to Puppydog Plenipotentiaries

Stimulus

Network Effects

SPACs as a Call Option on Hype

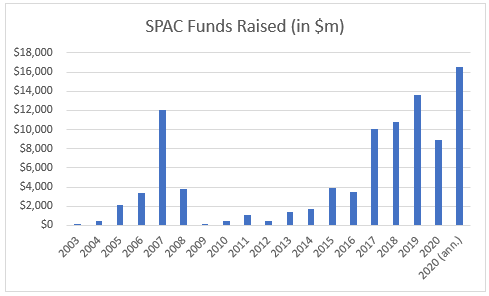

Special purpose acquisition vehicles have raised record amounts in the last few years. SPACData.com has tracked 28 SPAC IPOs this year, raising $8.9bn. At the current pace, that’s a $16.5bn run-rate, beating last year’s $13.6bn and massively ahead of the 2011-2015 average of $1.7bn.

|

SPACs have a simple model: raise funds, then find a company to merge with. When they announce the merger, shareholders can either accept stock in the new company or redeem their shares at the original price of the offering. So, to the SPAC issuer and the company the merge with, the SPAC is a deconstructed IPO. There’s a very short roadshow (you just negotiate with one investor). To the SPAC investor, it’s a subpar money market fund with a Kinder Surprise Egg-style option attached: invest, and for the cost of tying up your capital for a while, you have the option to get… something.

There’s been a recent blizzard of SPAC deals:

On Wednesday, a rare earth miner announced plans to go public via SPAC, with an expected market value of $1.5bn.

Bill Ackman’s SPAC planned to raise $3bn, a record. They raised their target earlier this week to $4bn, with a novel pricing mechanic. There’s a fixed pool of warrants to be distributed to all shareholders who accept the deal, so the more shareholders reject the deal, the more of the equity goes to the ones who accepted it. This sounds more like a game theory thought experiment than a useful feature, but we’ll see.

Nikola, DraftKings, and Virgin Galactic all went public through SPACs.

Where did they come from? What does it mean?

SPAC advocates say that SPACs are cheaper than the traditional IPO, and avoid the “IPO Pop.” Matt Levine has pretty thoroughly destroyed that theory:

Compared to an IPO, the SPAC is much less risky for the company: You sign a deal with one person (the SPAC sponsor) for a fixed amount of money (what’s in the SPAC pool ) at a negotiated price, and then you sign and announce the deal and it probably gets done. With an IPO, you announce the deal before negotiating the size or price, and you don’t know if anyone will go for it until after you’ve announced it and started marketing it. Things could go wrong in embarrassing public fashion.

…

The SPAC structure is less risky for the company than an IPO, which means that it’s riskier for the SPAC (than just buying shares in a regular IPO would be), which means that the SPAC should be compensated by getting an even bigger discount than regular IPO investors.

And that’s true.

SPACs are expensive for investors. One pseudonymous banker says:

Compare that to the average SPAC IPO size of $318m year-to-date, and that’s a pretty healthy vig. It omits the sponsor’s fees—typically, sponsors get 20% of the SPAC’s pre-merger equity. (Because of the redemption option, while this is technically equity, it’s equivalent to a call option that’s exercised on the date the SPAC’s acquisition closes. That’s still an enormous option grant.)

There are a few ways to look at SPACs:

They’re a generic expression of risk-aversion plus upside-sensitivity. It’s very common for structured equity products sold to retail investors to offer capital preservation plus some upside. The SPAC just offers a single-name version of the same popular product. (And, like structured products sold to retail investors, the numbers look a lot worse if you calculate the values of the implicit options involved.)

The SPAC boom is accelerating due to Covid, because IPO roadshows are hard to do, and don’t work as well remotely, so there should be a shift towards one-on-one deals rather than one-to-many capital raises. (I like this explanation, but it’s suspicious because it explains 2020, but 2020 continued a decade-long trend.)

It’s driven by the interests of promoters, rather than investors. Once there’s demand—and any given SPAC should be about as easy to sell as any other, since valuation isn’t an issue and there isn’t an underlying business to evaluate—you’d expect supply to meet demand.

But the most interesting explanation for SPACs is not that the IPO process is costly (it’s expensive, but cheaper than a SPAC), but that it takes a long time. And that’s especially challenging for companies that want to ride a hype wave. The dot-com bubble had incredible turnaround: DrKoop.com was founded in July of 1997 and filed its S-1 in March of 1999. Pets.com launched in November of 1998 and went public in February 2000. Hotjobs, a comparative laggard, was founded in February 1997 and didn’t manage to produce a prospectus until June 1999.

In the 90s, you could start a company, prep it for IPO, take it public, and white-knuckle your way through the lockup, all before the bubble popped. Today, there are higher standards and there’s a longer process. The market is not structured to quickly turn well-hyped businesses into public companies.

SPACs change this. If Nikola had planned a normal IPO, they’d probably schedule it for some time after they had a working product, rather than renderings of prototypes. It wouldn’t make sense to hire a big-name CFO this early, though there’s a long list of senior finance executives with EV experience to choose from.

The standards for SPACs are lower, so any time there’s a well-hyped trend, or the possibility of one, a SPAC is the right vehicle for a quick IPO. Nikola is not a coincidence. MP Materials, for example, is a trade war play; they’re the only US producer of rare earths, and China has used rare earth embargoes as a policy tool in the past. So now is a great time to offer the market a pure-play on domestic rare earths.[1]

Multiplan is another opportunistic SPAC deal: They’re a healthcare claims processing company, going public at 11x 2021’s revenue (and somehow 13x adjusted EBITDA. I’m in the wrong business). Multiplan is one of those companies that converts one-time operating expenditures into long-duration cash flows, which, when rates are low, have a very high net present value. So they’re also a timely bet.

Virgin Galactic doesn’t fit with the model of riding trends, but it does fit with the model of creating them. I was long the stock before the deal was announced, on the simple theory that Chamath Palihapitiya is a) smart, and b) more importantly, very willing to say crazy things on TV. For example, Slack had to disclaim any endorsement of, or responsibility for, the things he said about them on CNBC when they were in the middle of their direct listing process. Statements like “You know, one of our biggest investments is a company called Slack, and I still think to myself, why did we not just lead every single round and write the entirety of the fund into that company. It was obvious from day one that Stewart Butterfield is an iconic CEO, and that Slack is going to be one of the most important tech companies in the world.” I figured a crazy interview would either make the stock drop by half or double, and since I could redeem it for $10 either way, my free option was underpriced. The timing was off, but the thesis was right; Virgin was hyped to the moon, mostly by bored day-traders, and it did end up more than doubling.

This pattern means that SPACs tend to be very adversely-selected. The companies that go public via SPAC are not usually the ones that planned an IPO for a long time, but the ones that suddenly had an opportunity and really wanted to take it. The SPAC is the Vegas Wedding Chapel of liquidity events; it seems like an urgently good idea at the time, but doesn’t always turn out that way.

But in another sense, SPACs are a return to normal. The IPO process isn’t broken because it’s too expensive, just because it takes so long. And now it’s faster.

The form of finance is a lot more flexible than the fundamentals. Take risk tolerance: In the 20s, bucket shops offered their customers absurd amounts of leverage—up to 100:1 in some cases, so you could lose all of your money in one bad afternoon.[2] During the Depression, the Federal Reserve instituted margin restrictions, requiring investors to put up a set amount of collateral before borrowing.[3] But investors find a way to take risks, by speculating in small-cap stocks, uranium miners, and assorted fly-by-night operations. By the 60s, leverage started to move from investors' balance sheets to companies' balance sheets: you couldn’t get much margin debt, but you could get all the levered excitement you wanted by investing in deeply-indebted conglomerates. And then, by the 70s, retail trading in futures was getting big, and anyone with excessive risk tolerance could lever up as much as they wanted. (The pseudonymous “Dash Riprock” from Liar’s Poker and actual Jeff Skilling both lost money trading futures while they were in school in the 70s. There is nothing new under the sun.)

Regulators have flexibility in determining the form of risk tolerance. But they ultimately can’t change its existence that much. Some market participants crave volatility, and they’ll find it one way or another.

Similarly, regulators can make the IPO process slow. But some companies have a preference for speed, and some traders have very specific and urgent needs that can’t be satisfied in time by the usual way of going public. We are, as always in finance, somehow back to square one.

[1] I suspect their share price will have some interesting reflexive properties: a rise in their stock implies that Americans with money are worried about a rare earths embargo, which also implies that it would be effective, which could potentially make it happen. There are precedents: Armen Alchian figured out one of the components of hydrogen bombs by watching stocks, and his research was destroyed. A few decades later, Paul Tudor Jones mused that the world’s best commodity traders worked for the USSR.

[2] This sounds like straight up gambling, and it was: bucket shops didn’t execute customers' orders at the exchange; they basically offered a swap. This gave bucket shops a pretty simple business model: encourage all their most levered customers to buy the same stock. Then short the stock until the customers all got margin calls, and then buy it back. As long as the transaction cost of pushing a stock from $100 to $99, then covering, was smaller than the value of 99:1 levered customer deposits backing long in the same stock, this was profitable.

[3] This is done through Regulation T, which used to be a tool for fine-tuning the market to prevent or encourage speculation. Collateral requirements were 40% in the early 40s, hit 100% for a while in the late 40s, and bounced around between 50% and 90% until 1974, when they were set at 50% and haven’t changed since.

A Word From Our Sponsors

Here’s a dirty secret: part of equity research consists of being one of the world’s best-paid data-entry professionals. It’s a pain—and a rite of passage—to build a financial model by painstakingly transcribing information from 10-Qs, 10-Ks, presentations, and transcripts. Or, at least, it was: Daloopa uses machine learning and human validation to automatically parse financial statements and other disclosures, creating a continuously-updated, detailed, and accurate model.

If you’ve ever fired up Excel at 8pm and realized you’ll be doing ctrl-c alt-tab alt-e-es-v until well past midnight, you owe it to yourself to check this out.

Elsewhere

More on the Twitter Hack

Brian Krebs has identified a suspect in the Twitter hack. Interestingly, this hacker had used SIM card attacks in the past (a possibility I discounted in my post on Wednesday’s incident, since so many accounts got compromised). If Krebs is right about the suspect, then the thesis that the hackers were not financially sophisticated checks out. As does one non-monetary motivation for the breach: bragging rights.

Corruption, Liquor, and the China Bubble

Chinese equities had their worst day in months ($) after a massive 20%+ rally in the last three months. One reason: a negative story ($) about Kweichow Moutai, the megacap liquor/bribery company. Moutai is a vehicle for bribes: it’s popular among Party members, because Mao liked it, and some bottles are expensive but have a liquid market. Perfect for a plausibly-deniable bribe.

I’ve written before about how China’s corruption accidentally imposes some healthy economic incentives. Bribes usually pay for land and loans; a bribe for land is tantamount to a Georgist tax (which is economically optimal), while bribes for loans are something close to a Tobin Tax (which doesn’t work in practice, except in economies with a fairly closed financial system—like China’s). So Chinese equity traders are reacting in about the right way: in a system where bribes are necessary to get anything done, getting rid of an avenue for small dollar-value bribes means slower growth.

Q/Q^4 != Y/Y

A minor piece of economic trivia, almost never relevant, is that the US quotes GDP growth in a strange way. Most growth rates get quoted in year-over-year terms. Quarter-over-quarter can make sense for anything that grows fast and doesn’t have seasonality. But for some reason, we quote GDP growth by taking quarter-over-quarter growth and compounding it for four quarters. As Scott Sumner warns, this will lead to many non-comparable comparisons. The current Atlanta Fed Nowcast expects GDP growth of -34.5%, but that’s actually a 10% quarterly drop, extrapolated for a full year. Normally, GDP growth is not volatile enough for this to matter much, but Q2’s GDP numbers will make some needless noise.

Wolf Warrior Diplomats to Puppydog Plenipotentiaries

Via Politico’s China Watcher: China’s diplomats have occasionally drifted into very aggressive rhetoric, which has been dubbed “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy after a popular action flick. But recently, they’ve expressed milder sentiments:

One particular view has been floating around in recent years, alleging that the success of China’s path will be a blow and threat to the Western system and path. This claim is inconsistent with facts, and we do not agree with it. Aggression and expansion are never in the genes of the Chinese nation throughout its 5,000 years of history. China does not replicate any model of other countries, nor does it export its own to others. We never ask other countries to copy what we do. More than 2,500 years ago, our forefathers advocated that “All living things can grow in harmony without hurting one another, and different ways can run in parallel without interfering with one another”. This is part of the Oriental philosophy, which remains highly relevant today. The American people have long pursued equality, inclusiveness and diversity. The world should not be viewed in binary thinking, and differences in systems should not lead to a zero-sum game. China will not, and cannot, be another US. The right approach should be to respect, appreciate, learn from, and reinforce each other. In its reform and opening-up, China has learned a lot of useful experience from developed countries. Likewise, some of China’s successful experiences have also been quite relevant for some countries in tackling their current challenges. In this diverse world, China and the US, despite their different social systems, have much to offer each other and could well co-exist peacefully… Some friends in the US might have become suspicious or even wary of a growing China. I’d like to stress here again that China never intends to challenge or replace the US, or have full confrontation with the US. What we care most about is to improve the livelihood of our people.

This could simply be a matter of phrasing. Maybe one aspect of “growing in harmony without hurting one another” involves an invasion of Taiwan. A simple comparison of growth rates implies that the longer the US and China delay a serious confrontation, the better that confrontation goes for China. (Demographics complicate this somewhat: 2050 is better for China than 2020, but 2030 is a bit ambiguous.) So US policymakers should pay close attention to when China’s diplomats respond to escalation in kind, and when they suddenly start emphasizing peace, cooperation, and co-existence.

Another example of this: China says it will stick with the phase one trade deal. That’s interesting, because they’re not on track to adhere to it so far. But the thought counts.

More Evidence That the Next Stimulus Round Will be Slow

The $600/week unemployment top-up runs out at the end of this month, at which point either a) some level of transfer payments will be continued, or b) the US will switch to contractionary fiscal policy at a time when inflation is running at +0.6%, TIPS imply 5-year inflation expectations of +1.3%, unemployment is 11%, and the economy is otherwise signaling that more spending wouldn’t hurt and would probably help.

Negotiations are in progress. The latest: Trump wants a payroll tax cut to be part of the next deal. This is not a bad idea, at least coupled with continued unemployment benefits: the main goal of Covid economic policy is to put as much of the economy as possible into a deep freeze where debts can be serviced and people can get back to work as soon as it’s safe. But a payroll tax cut coupled with a drop in unemployment benefits creates a dangerous situation, where the government is subsidizing a return to work whether or not it’s safe to do so. The cost of an affordable stimulus that goes on for years is lower than the cost of a huge one that only lasts for months.

Keeping the Big City Network Effect Alive

I’ve argued before that superstar cities will not get hit as hard by the remote work phenomenon, because the network effect is driven by in-person meetings rather than work in offices. But network effects are just as important on the way down as on the way up: when people leave a city, fewer people have an incentive to stay.

New York is trying to address that: while schools won’t be fully open, the city will offer some daycare options to compensate. This is a very important tool for keeping white-collar workers in the city. It doesn’t make a ton of sense from a pandemic-prevention perspective: schools are dangerous if they spread diseases, and putting students in a room that’s labeled “daycare” instead of “classroom” doesn’t matter much to the virus.