In this issue:

Palantir: On Business, Cults, and Politics

Wirecard’s Scramble & Gamble

Global Yuan?

The Housing Boom

Financial Education for Future 1%ers

Alphabet Insurance

Palantir: On Business, Cults, and Politics

Normally when a company files its S-1, we have the standard debates: is this a good business, or a bad one? Are they going public to get capital or provide liquidity to employees, or is it a money grab?

Occasionally, we get to have the less interesting but more fun debate: is this company actually evil?

Palantir has been protested. They’ve done business with ICE since 2014. A Palantir employee allegedly worked with Cambridge Analytica. And, of course, they sell to law enforcement, intelligence, and the military, all institutions that are ultimately in the business of picking out certain people and making their lives absolutely miserable.

There’s another reading of the firm, though: political debates are defined by tradeoffs, and tend to assume an efficient frontier. So you can vote for the Civil Liberties Party or the Safety and Security party, but you have to choose. Technology is all about escaping those dichotomies: getting more outputs from the same input, which in this case means getting fewer crimes and terrorist attacks and fewer invasions of innocent people’s privacy. They’re aware that this is an incredibly fraught tradeoff, and that any intelligence product powerful enough to spot a potential terrorist network can also spot a free-thinking dissident. Their cofounder, Joe Lonsdale, says there’s a warning built into the name:

In the fantasy realm of Tolkien, the palantir seeing stones were made thousands of years ago by the elves of Valinor in the Uttermost West, and gifted to their friends around the world. These stones could communicate to help see the past and understand the future, and were used to secure the world by overcoming forces of evil. Unfortunately, in future ages, they eventually fall into the wrong hands and are used for corrupt purposes — their images distorted to pervert goals, and their power harnessed to further evil. What might their creators have done to prevent this — and was it still worth creating them?

Now, Palantir is prepping their direct listing, so we can have the business debate and the moral debate.

Palantir as a Business

Palantir sells software to governments and businesses to help them manage their data, make better connections, and spot dependencies and problems. One common knock against the company is that it’s not really a software company, but more of a high-touch consultancy with good PR. That’s not quite the picture you’d get from looking at their margins. Last year, Palantir’s gross margin was 67%, compared to 31% for Accenture and IBM’s services gross margin of 32%. Clearly, Palantir is doing something different.

Since they sell software to large enterprises—they have 125 customers, counting government agencies as separate customers, and had $5.6m in average revenue per customer last year—they do have the classic lengthy sales cycle common to most large deals. But in Palantir’s case, it almost seems that they deliberately slow their revenue:

They don’t have much of a sales staff, although they’re adding to it. Their CEO is involved in closing many of these deals personally. (A WSJ profile ($) from late 2018 says he traveled 250 days a year.)

It takes six to nine months to close a deal.

When they finally close customers, their initial deals are tiny. They break sales into phases, and the first phase is for customers who do under $100k in revenue per year.

They make technical employees rotate between developing products and working in the field with customers. That’s a way to do continuous R&D on customer needs, but it’s also disruptive.

Since Palantir doesn’t bring its own data, it has to integrate with each customer’s existing software, and then build processes and train users to make the product worth using.

All this means that money is flowing out long before customers generate any material revenue.

Palantir’s model has front-loaded expenses for long-term contracts. The dollar-weighted average length of their current contracts is 3.5 years, so most of their contracts are still in the early and costly phase. Palantir looks at their incremental margins through the lens of “contribution revenue”: gross profit minus sales and marketing expense (which includes configuration costs), ignoring stock-based comp. The stock-based comp exclusion is a bit of a stretch; it’s a non-cash cost, but certainly a cost. The rest makes sense.

Here’s how they describe it:

In 2019, customers in the “acquire” phase generated $0.6m in revenue, with a contribution loss of $65.4m Those same customers in the first half of 2020 generated $18.8m in revenue with $13.9m in contribution losses.

In the same year, customers in the “expand” phase generated $176.3m in revenue with a -43% contribution margin; in the first half of 2020 those customers generated $160.5m in revenue with a contribution margin of +35%.

Customers in the “scale” phase in 2019 were responsible for $565.7m in revenue at a 55% contribution margin, and in the first half of 2020 those customers did $296.3m at 68% contribution margins. The top 25 customers in this category had contribution margins of 87% last year and 89% so far this year, which puts Palantir at close to traditional software margins for its biggest and most mature accounts.

Palantir also notes that they usually seasonally weakest at the start of the year, and improve sequentially from quarter to quarter, so annualizing those first half numbers understates the growth. It’s interesting to contrast this with Asana: Asana’s gross margins are higher, because they have such a generalized product, based on a theory of work. Palantir’s initial margins are lower, because when they sell to Airbus they have to develop a Theory of Airbus, their army contract requires a Theory of the US Army, etc. But over a longer period, the unit revenue pictures look similar. Landing a customer is expensive, but once they’re in they stay in.

Palantir has also accelerated their process recently:

The time required for a customer to start working with their data in our platform has decreased more than five-fold since Q2 2019 to an average of 14 days in Q2 2020. In some cases, a customer can now be up and running in six hours. Integration with existing systems has also become faster. We have developed data integration connections for enterprise resource planning (“ERP”) systems used by many large organizations to manage their data, enabling customers to map their data into a generalized framework for modeling the real world and to start building applications in as few as 4 days in Q2 2020, down from as many as 45 days in Q2 2019.

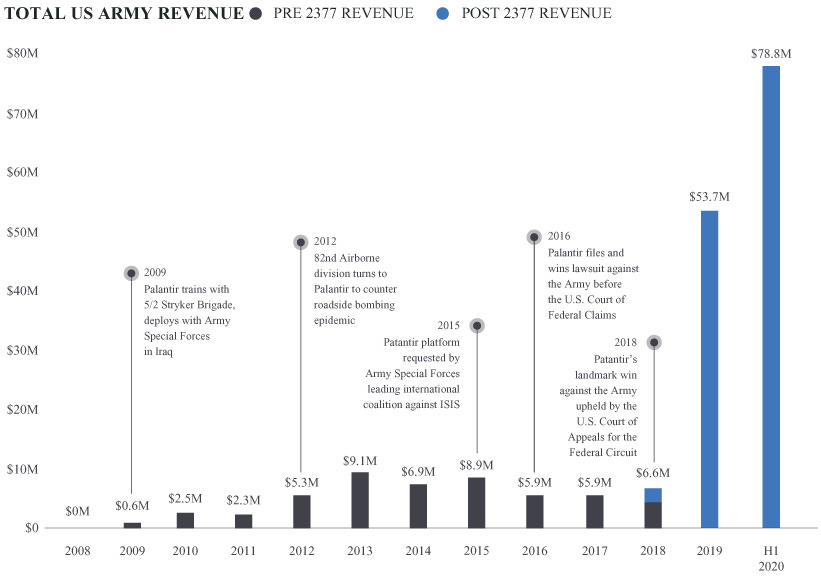

Government contracting is an interesting business, which complicates the picture a bit. For one thing, it’s not especially common to sue your customers. But the result of that lawsuit is even more surprising: revenue rose from $5.9m in 2017 (before the suit was resolved) to $53.7m in 2019:

|

While that’s a quirk of government contracting, it’s also the reductio ad absurdum of enterprise sales. The bigger a client is, the more the salesperson’s job is to figure out the internal org chart, and help the person they’re working with at that company find the decision-maker who can block or allow a purchase. Usually it’s a Senior Vice President of something-or-other; in this case it was the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

So one way to look at Palantir is that it’s going public in the midst of a turnaround: the company used to be slow to acquire customers, slow to ramp them up, and unable to do business with one major customer that had high demand for their products. All of those problems are getting better. This makes current growth artificially high—2021’s growth will be comping against all that incremental army spending, which will at some point slow down—but it does imply that the margin picture won’t be as dire.

Palantir as a Cult

Have you encountered The Cult of Palantir? It’s anecdotal, but when I lived in SF I noticed a higher percentage of Palantir employees wearing company-branded gear than at any other company. This kind of thing leads to some speculation that Palantir is a cult. From an investor’s perspective, this is pretty great news. “Cult” is just a euphemism for “ability to pay below-market salaries and get above-average worker retention.”

There are layers of meaning to calling a company a cult. Many successful companies are culty in one way or another—the Apple blog “Cult of Mac” was not named entirely tongue-in-cheek. Some companies are cultish with respect to customers, like Peloton, which literally sells access to a scheduled ritual that makes participants more virtuous. Bitcoin is a somewhat evangelical cult, whose adherents make serious claims about techno-financial eschatology and believe that all of their (monetary) actions should be recorded with perfect fidelity forever so they get precisely the consequences they deserve.

Cults are high-variance. You can get superior growth and focused pursuit of a variant thesis. Or you can get fraud that’s ostensibly perpetrated for the greater good. Normally, that would be a large risk, but Palantir is an unusually scrutinized company, with many high-profile and controversial projects, so if you’re looking for dirt you have lots of competition. Just by process of elimination, they seem to embody most of the positive aspects of cultish behavior.

Arguably we have too few cults—the world doesn’t have enough organizations pursuing oddball goals in secret. Palantir wants to “save the shire” and allegedly helped catch Bin Laden. How many companies can say that? If you want to work for an organization that a) wants to defend the free world, and b) regularly ships, you have few options. (But not just one! Anduril is hiring.)

Palantir and Politics

Government contracting is inherently political, at least once you start choosing which governments you’ll work with and which you won’t. In the S-1, Palantir says:

Our leadership believes that working with the Chinese communist party is inconsistent with our culture and mission. We do not consider any sales opportunities with the Chinese communist party, do not host our platforms in China, and impose limitations on access to our platforms in China in order to protect our intellectual property, to promote respect for and defend privacy and civil liberties protections, and to promote data security.

And in an interview with Mathias Döpfner, Karp says “our primary interest is a stronger West.” (12:40 in that recording.) Later on, he says that the reason Palantir can recruit well is that it’s trying to turn a tradeoff into a solved problem: stop terrorism and preserve civil liberties. If politics is about tradeoffs, technology is about eliminating tradeoffs. Palantir embodies this quite literally, inasmuch as their CEO calls himself a socialist and their chairman was a large donor to Trump in 2016.

Palantir’s relationship to privacy is highly dependent on exactly where you draw the creepy line. They collect data to make inferences about behavior, and in their intelligence work that means collecting data to identify potential terrorists. Their users certainly consume more data than they would with a manual counterterrorism approach, but the outcome is that less of it gets looked at by humans. So the difference is between abstract but extensive privacy violations (your phone/text metadata, financial transactions, and other behaviors all factor into their model) and literal but less common ones (someone manually reviewing the same things to decide if your Venmo transaction with the memo “Dinner at Afghan restaurant” indicates that you might be training with the Taliban.) What’s worse, the possibility of a human manually snooping around your personal information because you got unlucky, or the extremely high probability that an algorithm will review your behavior and flag it as totally innocuous with no human intervention?

Palantir is certainly sensitive to political shifts. They say as much in the S-1, and have said so elsewhere, too. But the picture is not quite what one might expect. They started to generate revenue in 2008. In Obama’s second term, revenue compounded at 37% annually, reaching $466m in 2016. In 2017, growth slowed to just 11%, and their annual growth under Trump has been just 17%.

The way they describe their views—and the way they contrast them with other tech companies—is that they’re ultimately deferring to what voters want. As Alex Karp puts it:

What is worrisome is that some Silicon Valley companies are taking the power to decide these issues away from elected officials and judges and giving it to themselves — a deeply unrepresentative group of executives living in an elite bubble in a corner of the country. They weigh their beliefs along with their complex business interests, both domestically and globally, and then make decisions that impact the safety and security of our country. This is not the way consequential policy decisions should be made. I don’t believe I should have that authority.

Deferring to voters is not exactly an ideal standard, but it’s a consistent one: the object-level debates are complex and challenging, but the meta question is whether policy should be made by technology executives or by the established institutions that are designed to make such decisions. And it ties in with Palantir’s cultural bias towards defending the values of the US and its allies.

The debate quickly descends into murky territory, somewhere between the Crito and G. A. Cohen’s “German political philosopher” bit. Every government has to do things that some of its citizens find appalling. That’s basically what governments are for; if there’s unanimous agreement about how to resolve some issue, there’s no need for an organization to debate it and resolve it. The question from Palantir’s perspective is, once a policy is decided, whether it should be implemented well or poorly; should US counterterrorism involve ad hoc, poorly-coordinated privacy violations, or should the data the government already collects be collated into some usable form so the actual threats can be identified and mitigated? Does immigration enforcement involve stopping people who look suspicious to an individual ICE agent or identifying people who are, in fact, knowingly violating the rules? Palantir is participating in a very morally messy business. It’s hard to have a long land border between two countries with disparate GDPs per capita. (Mexico has the same sort of problem ($) on its southern border.) Politics is the art of determining which difficult moral tradeoff you make, and Palantir’s job is, as much as possible, to minimize the extent to which it’s a tradeoff at all.

Companies have limited flexibility to overrule the democratic process if it doesn’t reach their preferred outcomes on contentious issues. But companies that sell to the government can offer tools that replace random interrogations with a more targeted approach. Palantir exposés have to read between the lines pretty aggressively to turn an ICE department “mainly tasked with investigating serious cross-border crimes like drug smuggling, human trafficking, and child pornography,” into a mostly deportation-focused product—and they have to ignore the fact that, since Palantir started working with ICE, deportations have declined. If you’re sure Palantir is in the wrong, you’re probably not scrutinizing the counterfactual; if you’re sure they’re in the right, you have more confidence in them than they do internally, because they openly say that there’s a vigorous internal debate over the morality of some of their contracts.

Conclusion

Palantir is a strange company in a complicated industry. If they’re a consulting shop with a great sales pitch, they’re clearly overhyped—the sales pitch might land them clients and get them cheap employees, but that should be visible in their margins by now. If they’re a software shop whose software is complicated enough that it requires a significant investment of developer time, though, they have the natural advantage that all complex products have: Palantir will pay the cost to install it, but the customer is on their own when they try to get rid of it. Palantir’s overall margins look awful, especially for a company of its maturity, but unit revenue looks better the bigger its customers get and the longer they’ve been using the product. And since Palantir sells to some of the biggest customers on earth, over time their overall margin picture will be dominated by those giant, mature accounts.

The challenge for the company is to spread their narrative in the face of a widespread counter-narrative about spying, secrecy, and having their stock comped to IBM and Accenture instead of Servicenow and Salesforce. And the challenge for outside observers is more stark: if Palantir isn’t evil, it’s a uniquely virtuous company, one that’s forcing itself to make challenging decisions rather than taking easy defaults. It’s fine for any one company to shrug and say that law enforcement and defense are so morally murky that it’s not worthwhile to work with them. But the world needs people and institutions with agency, who weigh the tradeoffs and actually make a decision. The fully generalized criticism of Palantir is a compromise through presumed incompetence: the expectation that bad laws will get passed and will fortunately prove unenforceable. That’s a bad way to make decisions, and morally lazy; it leaves outcomes up to chance, and means that every improvement in technology or institutional capabilities makes the world a worse place by default. Palantir is a more optimistic bet: that the moral challenges will never completely go away, but that we can at least improve the tradeoffs we face.

Elsewhere

Wirecard’s Scramble & Gamble

The FT, which has been doing extraordinary work on the Wirecard fraud, has another followup ($), with a new twist. Most frauds start out small, but if the magnitude of the fraud compounds faster than the core business, the fraud eventually eats the rest of the company. So at first the exit strategy is simply to fudge the numbers a little bit and catch up later. But when a company is mostly fake, what can it do? Wirecard’s answer: buy Deutsche Bank. Given how negligent Wirecard’s auditors and regulators were, this could very well have worked. If a legacy bank gets taken over by a zippy fintech company, you’d expect the fintech company to identify parts of the bank that ought to be written down; that would have given Wirecard a graceful way to take a writedown that reflected the size of their fraud, and then go legitimate.

There are two practical problems with this, in addition to the ethical problem that it’s covering up theft by stealing even more. First, the problem that did them in was timing: their auditors had finally realized that Wirecard was not exactly forthright about how their business worked and whether or not it made any money. And second, fraudsters commit fraud because they’d like their lies to be true. If they find a cost-effective way to stop lying, they still lose, even if it saves them from jail time.

Global Yuan?

China is gradually growing its SWIFT alternative ($), which now works with 948 financial institutions, up 48 from year-end. (SWIFT is over 11,000, so there’s a long way to go.) China is still far from making the Yuan a global currency, though. Historically, capital controls are incompatible with reserve status except in cases where reserve status is designed into the system, as was the case with the dollar during the Bretton Woods era and the pound in the first half of the twentieth century. This is why the more meaningful de-dollarization headlines ($) are more driven by China and Russia using Euros than their local currencies.

The Housing Boom

Yesterday’s new home sales were well above expectations. This makes sense; Covid and the attendant policy changes create the best imaginable circumstances for housing. Rates are low, the marginal buyer is more location-agnostic than usual (so housing demand isn’t throttled by restrictive zoning in the most popular markets), and construction is an activity that’s safer because it happens outdoors.

Financial Education for the Soon-to-be 1%

One startup from this summer’s Y Combinator batch has raised $16m on a $59m pre-money valuation for its equity compensation tool. Understanding the equity portion of startup compensation is usually pretty easy: just round it down to zero and see if the job still sounds worthwhile. But for startups that do work out, the range of outcomes is wide. So Trove ends up being in the business of explaining financial outcomes to newly-minted millionaires, which is a great position for a financial services company to start in.

Alphabet Insurance

Every successful tech company eventually turns into a bank, but Alphabet is extending the model and becoming a financial supermarket instead. They’ve launched an insurance company under their Verily business, which helps self-insuring companies protect against catastrophic losses.

Coefficient’s precision risk solution is designed to provide self-funded employers with more predictable benefit plan protection. It uses an analytics-based underwriting engine to identify unexpected areas of cost volatility, and cover those exposures with more dynamic and precise insurance policy provisions.

Basically dynamic hedging for health insurance. Small companies are in an unenviable position, where their business often can’t support generous insurance benefits, but holding the risk themselves means that one unhealthy employee can eliminate the company’s profits. (This happens even to large companies: AOL cut employee retirement benefits after some unexpected healthcare costs raised the overall cost of providing their benefits, and provoked a media firestorm when they got specific about the reasons.)