|

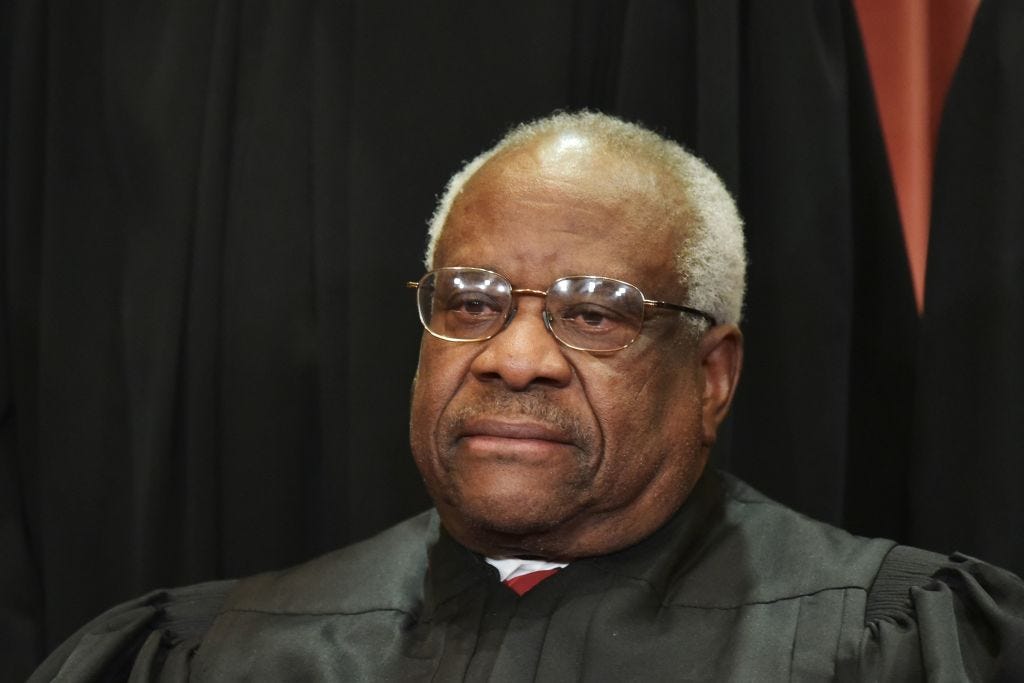

MANDEL NGAN/AFP via Getty Images

Platforms created by major tech companies — Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, etc. — are routinely used to incite violence, spread misinformation, and coordinate harassment. Occasionally, one platform or another acknowledges it has a problem and announces a new policy to crack down on the misconduct. The policy, however, is weak and poorly enforced. Things get worse. And the cycle continues.

Since 2016, for example, Facebook has made numerous announcements about its efforts to reduce the spread of misinformation. But, according to a new study, "Facebook likes, comments and shares of articles from news outlets that regularly publish falsehoods and misleading content roughly tripled from the third quarter of 2016 to the third quarter of 2020." How does this happen?

One reason is that technology companies have broad protections for liability for content posted on their services. The root of these protections is Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which became law in 1996.

Section 230 has two critical provisions. First, "[n]o provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider." In other words, if someone posts something defamatory on Twitter, the courts won't view Twitter as the entity that spoke or published the content. Second, an "interactive computer service" will not be held liable for "any action voluntarily taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected." This means that YouTube, for example, won't be held liable if it makes good faith efforts to moderate its service.

But have the courts interpreted Section 230 correctly? On Tuesday, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas issued an unusual 10-page opinion arguing the courts have gotten Section 230 wrong. Thomas argues that the courts are giving tech companies like Facebook and Google more legal protection than they are entitled to under the law.

Thomas' opinion was attached to the Supreme Court's decision not to hear a particular case, known as a denial of a writ of certiorari. Thomas agreed with the other Justices that the Supreme Court shouldn't consider this particular case. But Thomas used the opportunity to argue that the Supreme Court should consider the scope of Section 230 sometime in the future.

Some were quick to assume that Thomas' opinion was a sop to President Trump, who has recently called on Section 230 to be repealed as retribution for social media companies removing or annotating his false claims about COVID-19 and voting. But a close reading of Thomas' decision makes it clear that is not the point. (Biden has also criticized the broad protections Section 230 confers on large tech companies.) Whether or not Thomas is right, his argument is delete worth considering.

The problem with the court's interpretation of Setion 230, according to Thomas

Thomas notes that courts have interpreted Section 230 "broadly to confer sweeping immunity on some of the largest companies in the world." He argues that lower courts have gotten it wrong in a couple of ways. (Section 230 has never been considered by the Supreme Court.)

First, Thomas agrees that Section 230 protects technology platforms from "the liability that sometimes attaches to the publisher or speaker of unlawful content." But Thomas argues that Section 230 allows platforms to be held liable as distributors. Under legal precedent, distributors can be held liable for distributing content "when they knew (or constructively knew) that content was illegal." Nevertheless, in the 1997 case of Zeran v. America Online, a federal court ruled that Section 230 "confers immunity even when a company distributes content that it knows is illegal." There is nothing in the text of Section 230 that provides immunity in that case, but the court in Zeran argues it was a logical extension of the policy and purpose of the statute.

Thomas argues that Zeran is wrongly decided. If his view were to prevail, platforms could be held liable for failing to remove illegal content after they became aware of it. This might make platforms more responsive to reports from users about such content.

Second, Thomas believes that the courts should more carefully scrutinize decisions by platforms to remove content, arguing such decisions should only be protected when done in "good faith." Thomas cited the case of Sikhs for Justice v. Facebook. Here is a summary of the case by law professor Eric Goldman:

Sikhs for Justice (“SFJ”) is a human rights group advocating for Sikh independence in the Indian state of Punjab. It set up a Facebook page for its organization. SFJ alleges that, in May, Facebook blocked its page in India at the Indian government’s behest. Facebook allegedly did not restore access to the page despite repeated requests, nor did it provide any explanation for the page block. SFJ sued Facebook for several causes of action, including a federal claim of race discrimination.

Ultimately, a federal appeals court found that Section 230 protects Facebook from claims that it removed content in a racially discriminatory manner. Thomas argues that this level of deference to Facebook's content removal decisions goes too far. It's not that SFJ should necessarily win their case. But Thomas argues the group should be able to present evidence in court that Facebook discriminated against them on the basis of race.

Platforms as products

To demonstrate the court's overreach on Section 230, Thomas also references the case of Herrick v. Grindr LLC. That case involved a man named Matthew Herrick, whose ex-boyfriend, Oscar Juan Carlos Gutierrez, was impersonating him on the gay dating app Grindr. Carrie Goldberg, Matthew Herrick's attorney, explained what happened to her client:

It all began one day in October 2016, when a stranger appeared at Matthew's home address insisting that he had DM’ed with him to hook up for casual sex. Later that day, another person came to Matthew’s home. Then another and another. Some days as many as 23 strangers came to Matthew’s home and his job – waiting for him in the stairwell outside his apartment and following him into the bathroom at the Manhattan restaurant where he worked the brunch shift.

...Using Grindr’s patented geolocation functionality, he’d pinpoint exactly where he knew Matthew to be and then he would claim that Matthew had rape fantasies and free drugs to share. Sometimes, Gutierrez would stoke Grindr users, saying racist and homophobic things to users. Matthew would never know if the random men ringing his doorbell at all hours of the day and night were there to rape him, kill him, or both.

Herrick repeatedly contacted Grindr, which bans its app from being used "to impersonate, stalk, harass or threaten." But Grindr did nothing. Herrick sued and, in court, "Grindr claimed it was impossible to ban fake profiles." Goldberg aruged that if Grindr was unable "to identify and exclude abusive users" it was "a defectively designed and manufactured product." The suit, according to Goldberg, had nothing to do with the speach of a third party. It was about how Grindr created and designed its service. A federal court, however, "dismissed Matthew’s lawsuit at the earliest stage possible, ruling that Section 230 completely immunized Grindr."

It's unusual to find Thomas and Goldberg on the same side of an issue. Goldberg is known as a "pioneer in the field of sexual privacy," representing victims of of sexual harrassment and abuse in court. Justice Thomas is an arch conservative, highly skeptical of tort claims, who was accused of sexual harrassment by Anita Hill and others.

Goldberg told Popular Information that she was suprised by Thomas' opinion. But she praised it as "an excellent and clear-eyed rendering of the law and the problems with courts' overbroad interpretation which goes against the text." Maybe he's on to something?

|