One of the most quintessentially American experiences is wandering the shopping mall. The scintillating scent of Cinnabon wafts across the linoleum floors. Angsty youths spill out of the theater, chattering about the latest Marvel movie. Foot Locker sales staff judge you by your level of sneaker heat as you walk in. You can picture it right? In my current home of Salt Lake City, the crème de la crème of consumer excess is City Creek Mall. With a literal creek stocked with local trout running through the facility, it is the nicest shopping experience in the state. This is where you go to spend money.

As my partner and I meander from store to store we get a variety of experiences. At Tiffany & Co (62.5% gross margin) we are met by a burly security guard in a black suit gently opening a glass door. Inside we are treated like royalty with attendants attuned to our every need. Note: In other Tiffany locations they will often offer champagne as you shop but not here, this is Utah after all. Four stores down at Lululemon (56% gross margin) the attendants are more astute to our status in life. They sense we are too poor to shop there (an occupational hazard of being writers) and promptly ignore us the entire time. H&M is a screaming horde of hormones, with cluttered $10 t-shirts everywhere (50% gross margin). The Gap is a sad place no one goes (44.1% gross margin).

Despite the contrast in goods and quality of service, all of these stores are somewhat close in gross margin. That variance is the focus of today’s explainer. How can it be that ultra-luxurious experiences have similar financial profiles to terrible ones?

This is the third piece in an ongoing series for Napkin Math where we work our way down the income statement. The goal is to help you not just vaguely understand the fundamentals but to help you move past the boring/impenetrable terminology to real-life application. If this is your first time joining us, you should check out my previous two pieces on revenue and cost of goods sold. Today we are moving one line down the income statement to gross margin. As with all things finance, the definition is simple but the application is nuanced and important.

Gross Margin Fundamentals

Accounting was invented for the discovery of nuance. The more intimately you understand the patterns of a businesses’ financial movements, the more accurately you can assess risk or decide what to do. Gross Margin was invented for just such a purpose.

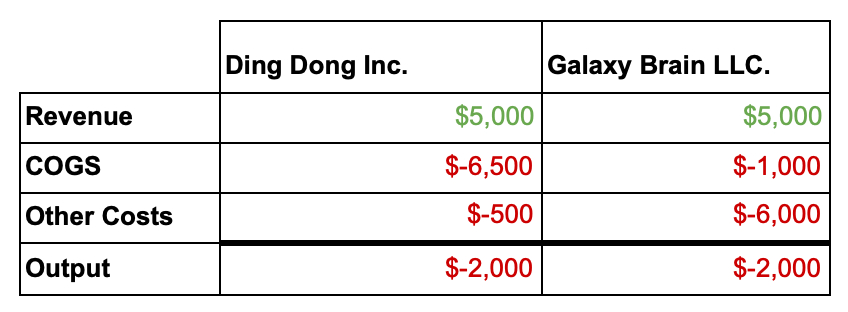

Last time we chatted I showed you this chart.

In it, we use revenue (the income your business is bringing in) and COGS (the directly associated cost of creating the goods/services sold to create that revenue) to create the mysterious category of “Output.” Gross Profit is that man of mystery. It acts as an indicator of scale. The higher the gross profit, the greater the total volume of money flowing through the business.

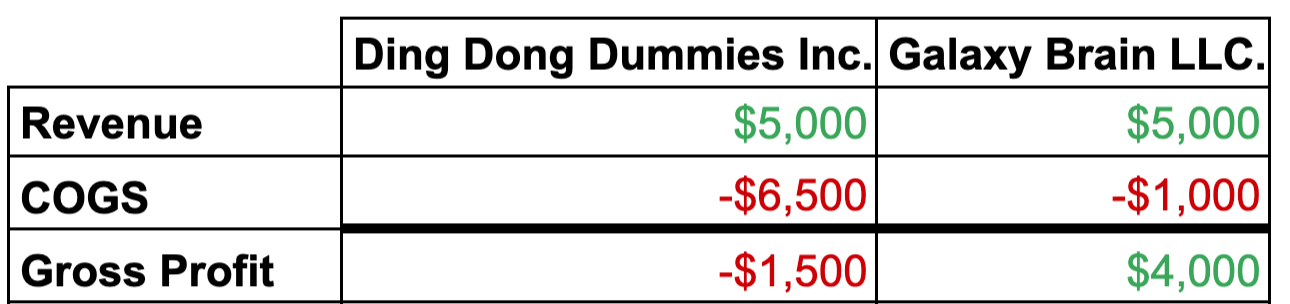

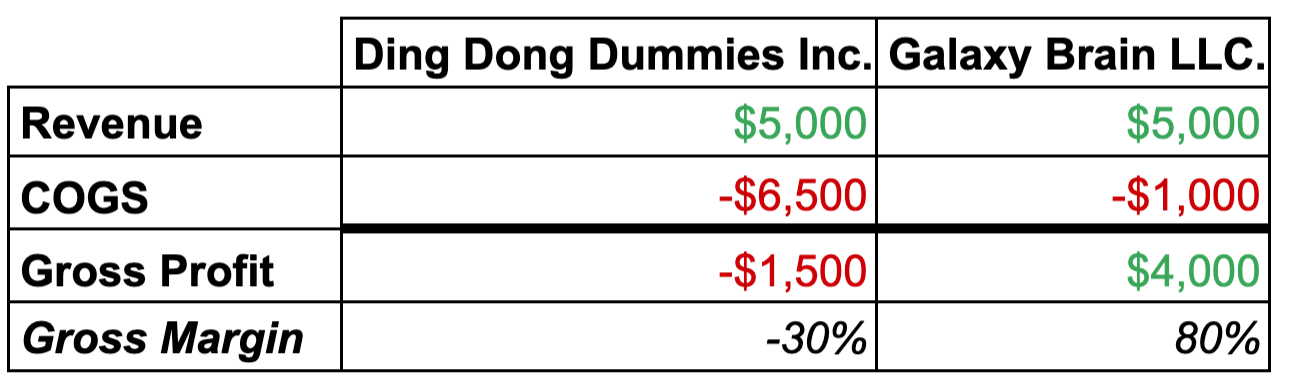

What is more interesting is the relationship between revenue and COGS. This is signaled by the Gross Margin. The formula is simple. Gross Profit / Revenue = Gross Margin

Note: I had maybe 10ish readers ask for me to show more of the accounting math in these explainers. If you think those people are wrong, write into the comments and tell me. I read every comment, even the mean ones :(

If the total amount of Gross Profits tells you something about the scale of the business, then what does the Gross Margin tell you? By understanding gross margin, especially in relation to the businesses’ peers, you are able to understand market power.

A business that has market power is a business that can buy low and sell high. In other words, if you want more power, you need to find a way to have a relatively strong gross margin.

As a business owner, you want the revenue of the item you sell to be more than the cost it takes to produce it. However, despite you being the one to make your good and despite you being the one to decide how much to sell your good for, you aren’t actually in total control of how much money you make per item. You can only influence it. Instead, competitive and market dynamics dictate how much you can charge, and how much it costs you to bring your product to market.

To help us understand that, let’s use an examination of the first store in the mall we mentioned above: Tiffany & Co.

What Sparkly Rocks teach us about Finance

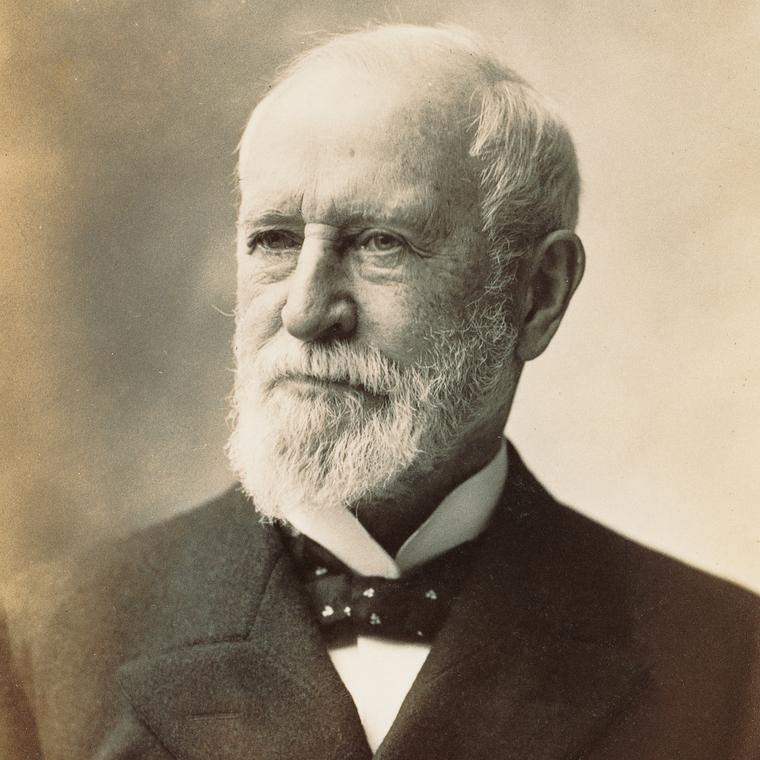

Tiffanys is perhaps the one great American luxury brand. Started in 1837 by Charles Lewis Tiffany, the company had its start in New York City. Their founder won his title “The King of Diamonds'' when he purchased ⅓ of the French Royal Jewels in 1887. He established the simple, clean aesthetic that Tiffany holds true to today. Perhaps equally iconically, his company started an early version of the trademark Tiffany Blue at the world fair in 1889. By the time he died at the ripe old age of 90 (I once heard a 90-year-old describe being that aged as “surprised to be not dead yet”) the company was widely recognized as America’s most prominent Jewelry company.

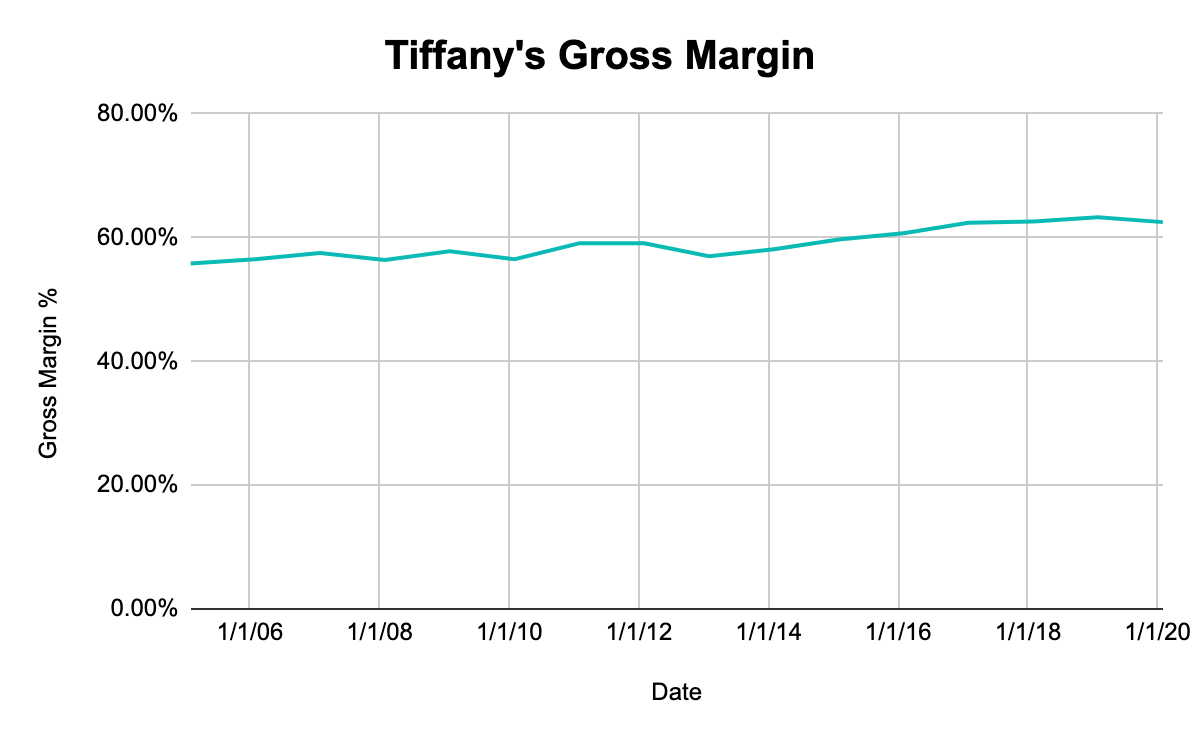

Fast forward to today and they have been acquired by LVMH (which was just covered in a fantastic piece by The Generalist) for $15.8B in January of this year. They were sitting around ~$4.4B in revenue spread across 326 stores. Far beyond the humble beginnings of a single building in New York City! One of the companies most impressive attributes was their gross margin. Through global crisis or economic boom, they had rock solid (sorry) margins for over 15 years.

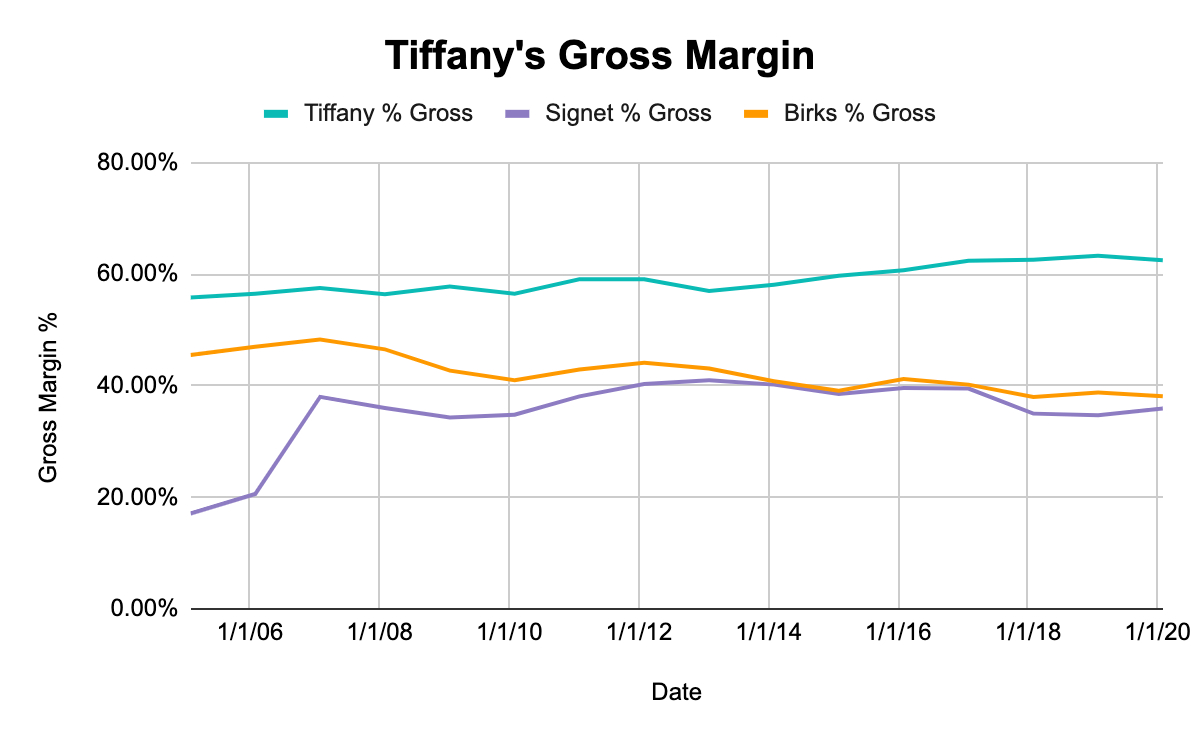

Impressive, but even more impressive when you contrast it with its peers of the sparkly rock. Signet Jewelers, the owners of brands like Jared’s and Kays, and Birks Group, a Canadian Jeweler.

Tiffany’s has actually increased its margin while its peers have simultaneously seen slow decreases over recent years. So why? Why did this occur? It isn’t like there is some spectacular deal to be had at Tiffany’s. They have never had so much as a sale in their 150+ years of existence. Their jewelry on a good day costs several thousand dollars with pieces ranging up into the millions. Not to lean too heavily into the title of this article, but the existence of this level of retail-fueled opulence feels a little... gross.

Regardless of whether people should be buying jewelry worth millions of dollars (spoiler, they should not) the fact they have had such consistently superior performance is impressive.

The Gross Margin Levers

Being able to make more money with less effort is an ideal business (and really an ideal job too). Gross Margin is a kinda, sorta accurate metric to signify that Tiffany has figured out the good life.

If you want to improve your Gross Margins, you have two options:

1. Reduce COGS

2. Increase price

With some businesses they are able to gain massive cost reductions as they scale thanks to increased purchasing power (bulk buying), more experience leading to greater efficiencies, bargaining power over suppliers, etc. But at a certain point Tiffany diamonds are going to cost what they're going to cost and you can't go any lower than that.

So that leaves us option 2, increasing price. The problem with that is usually when you raise your price people buy less of your thing. This is especially the case in markets where there are lots of competitors offering products that get the job done just as well as yours. So even though you might improve Gross Margins by increasing price, you risk reducing overall Gross Profits.

So how do you do both? Power. This is the whole subject of Divinations (my sister publication covering strategy), but let's look at it specifically in the case of Tiffany's. They chose 3 primary levers.

First is and most important is brand. When I put the iconic shade above, most of you instantly knew what business I was talking about. They have, for over 150 years, consistently and constantly positioned themselves as premium luxury brand. They spend hundreds of millions of dollars each year. Facebook ads, traditional marketing channels, you can find their hue everywhere you turn. This investment on brand isn’t just a marketing thing either! To signify their class and stature they place “Elegant stores in the best ‘high street"’and luxury mall locations [which] are more expensive and difficult to secure and maintain, but reinforce the Brand's luxury connotations through association with other luxury brands.” Their retail space screams, “poor people don’t enter here.”

Second, this investment in the brand allows them to expand their product line. By lending their colors to products beyond high-end jewelry they can charge gut-wrenchingly high prices. Their “everyday objects” feels like an extended joke but has been going for 4+ years now. $375 Gold Straw? Check. How about a $525 sterling silver 6-inch ruler? Their $1200 ice bucket puts Yeti to shame.

My guess would be that their margin is likely higher on these types of vanity items. Since so much of it is silver and gold (where there is going to be more competition on the supplier side) they will be able to eek out more margin.

Finally is vertical integration. Tiffany sources their diamonds directly from the mines, does all design in house, uses their own artisan craftsmen, and almost universally only sells their goods in their own stores. Note: They do sell watches and glasses in other retailers. In the diamond industry, middle men will mix multiple sources of diamonds together in batches to sell. By cutting them out, Tiffany is able to trace its diamonds all the way to its source and not have to pay the fees associated with their services. This again allows them to tell a better brand story, “Our diamonds are sourced ethically.” Conveniently, ethical diamonds happen to cost more! What a coincidence! (I honestly doubt there is anything that is a truly ethical natural diamond).

All of these things have allowed Tiffany to have a ~20% gross margin advantage over its peers for 15 years.

Alright now ignore everything I just said

But as always with finance, don’t over index on this metric! Finance is more of a mystery than a certainty. We dove deep on Tiffany & Co today because it was the best example I could find of how gross margin can act as an indicator of market superiority. But that it has a higher gross margin than its peers does not make it a superior business. Shoot, Lululemon’s yoga pants are pulling in the similar gross margin while the company is at 4x the market cap! They are all in the same mall (literally and metaphorically speaking). As you shop for assets, whether that asset is on the public markets or is an asset you are choosing to invest in, in your own business, you can’t be drawn in by one number. Gross margin is an example of that. It might be a soaring Redwood, a pillar of financial strength, but you’ll miss the forest for the trees if all you care about is how much money they make per dollar sold.

Maybe someday Napkin Math will release power rankings of my favorite financial metrics to look at, but for now, know that Gross Margin isn’t high on that list. Ensure that it is line with market/industry averages and then move on. There are more interesting, delicious things to nibble at. If you want to learn what those are and keep receiving financial concept explainers click the button below. If you join as a paid subscriber you’ll also gain access to my in-depth financial analysis of fascinating concepts. Last week, I examined my own employment contract with this publication to see if I was getting ripped off. (Yes really).

Till next week,

e

P.S. I frequently feature guest writers (next week's piece is especially interesting). If you have something novel or surprising to say about finance, DM me on Twitter with a pitch. Our list is large and you will be paid!