TL;DR

- This piece was informed by conversations with multiple growth practitioners in video game companies.

- Free to Play video game companies, by the structure of their market, are faced with the choice to either A) create addictive products that rob a select group of users large amounts of funds, or B) exit the business entirely.

- This is because their model doesn’t work at all without “whales”—high spenders that are manipulated through product design.

- This isn’t just limited to free-to-play video games. All companies land somewhere on the spectrum of harm. As each of us grow our companies, we must ask ourselves how we are causing hurt and if that tradeoff is justifiable.

Walking into the office, you would have no idea that the company was being held hostage by their business model. This was a top-three mobile gaming company in the U.S., just on the verge of releasing their newest game, with multiple major hits under their belt. The receptionist greeting me at the front desk matched her glaringly yellow company shirt with an equally incandescent, aggressively white-toothed smile. To her left and right sat fishbowls filled to the brim with strawberry flavored Laffy Taffy. Beyond her, workers lounged in bean bag chairs, chatting amicably with colleagues. My Midwestern sentimentality for everything pleasant buzzed. Not an inkling of the interview I was headed into that would end up testing my Minnesota Nice politeness to its extreme.

The position I was being recruited for was a “Strategy and Growth Manager.” Note: I am aware that the title is a Frankenstein’s monster of corporate gobbledygook that means absolutely nothing. My whole career has been spent in generically named roles like this, but in cavemen speak, when you hire me it is to “make company more money faster please.” It is a good career and one that has kept me intellectually engaged.

There is a downside to this type of job. My mandate is to make revenue go up and to the right, in whatever manner is most effective. Most of the time that isn’t a huge issue! My hometurf of B2B software isn’t all that world-changing and is delightfully dull. However, in the business of this game studio, you are dealing with individual consumer’s very limited time, attention, and money. When this happens, things tend to go… wonky. Individual wellbeing may be considered by management but is never an incentivized outcome.

My experience interviewing at this company acts as a good demonstration of the tension inherent in the desire to grow. All industries are held subject to the power structure of their market. When you add competitive dynamics into the mix, it can mean that an organization sometimes has no choice but to make morally dubious decisions (assuming they want the business to survive). This is true of all companies, not just mobile games! At a certain scale, every product/organization will end up hurting someone. There is always a percentage of the population that will be the recipients of direct or indirect negative effects from an organization operating.

Let’s start by going back again to this video game interview and use them as a case study about the complications of growth.

No really, I speak whale

When I finally sat down with my interviewer, a sharp-eyed former management consultant from BCG, she began to explain to me the basic business model of a free-to-play (F2P) game. In the world of video games, there is one mythical creature that you want to pursue to make money: the “whale.” The whale is an individual who, for whatever reason, chooses to spend hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars on in-game purchases. These angels of revenue are so heralded because there is no capped upside. In contrast with a typical video game, where you would try to get as many people as possible to make a one-time purchase of $60 bucks for a game, a F2P game focuses on getting as many free people as they can playing. Once they are playing, companies will focus on selling as many digital goods as possible. While there is an upper limit on how much you can charge for a game, there is no limit in the number of meaningless digital tokens you can hock.

As in lots of tech companies, the business is driven by power laws. The majority of the F2P industry exists on the back of this very, very small percentage of its total player base. All that matters is getting and keeping whales.

To illustrate why this business model works so well, let’s do a little Napkin Math. Note: I validated this model with several friends who are in the video game industry. The distribution here is generous toward people paying and is leaner for the average game but it makes my point easier to understand.

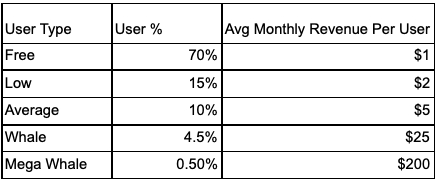

Let’s assume you magically start with a million monthly active users. Your revenue breakdown will typically look like this:

The vast majority of your users will be free. You can kinda monetize them with ads, but you are really only going to see a buck or two of revenue per month per user. The real money is found in the in-game digital purchases. These are the skins on Fortnite characters, an extra life in Candy crush, etc.

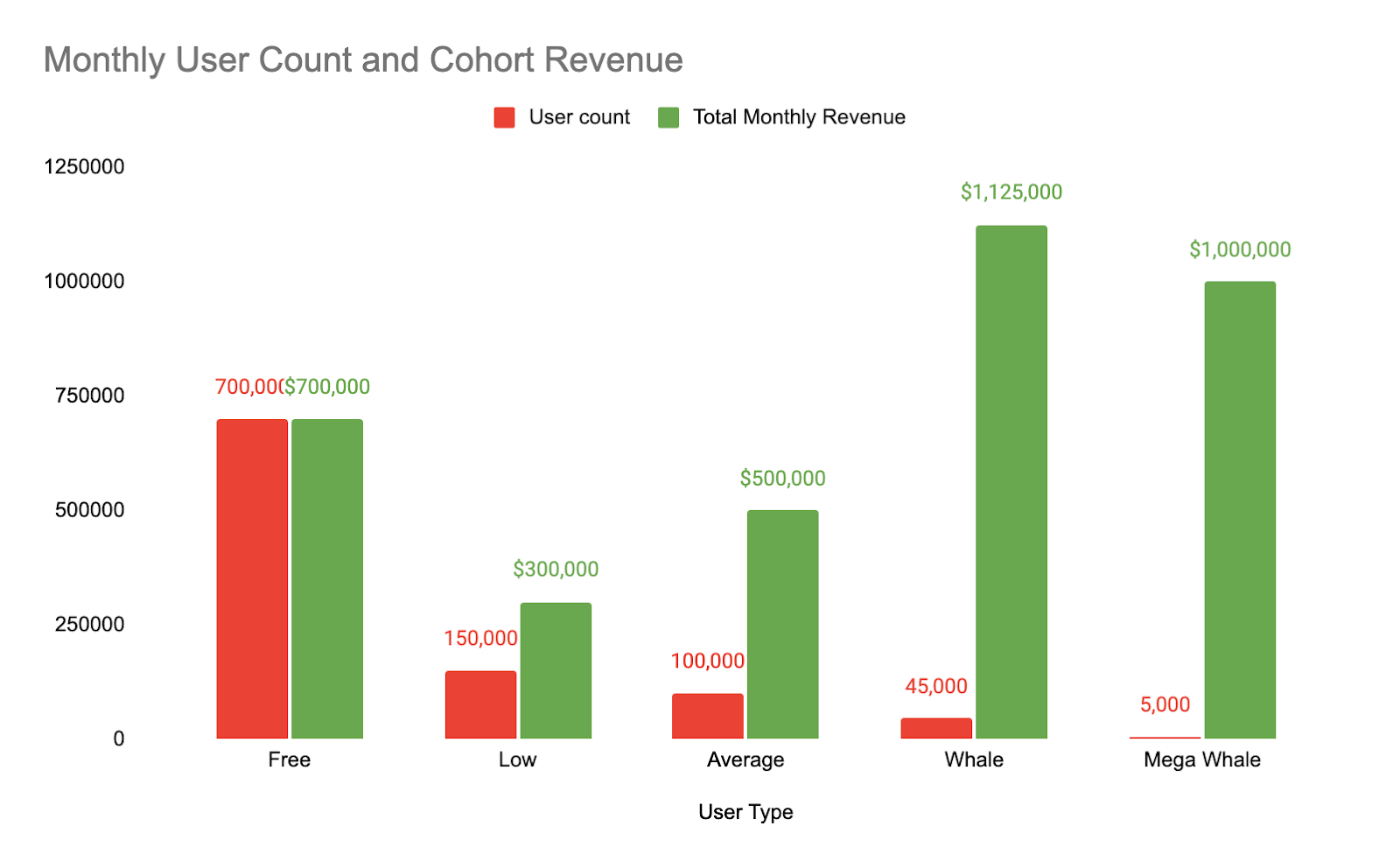

The group of people willing to spend money might be small, but boy are they mighty:

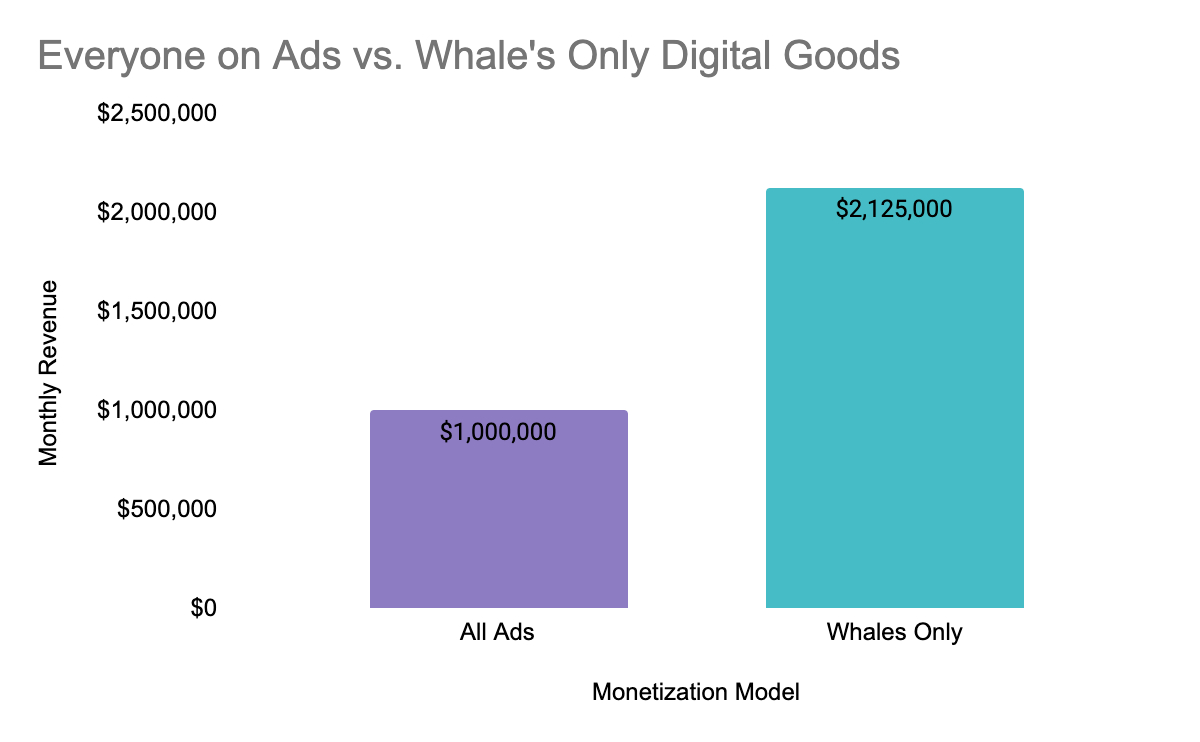

By cultivating a stable of whales, you’ll be able to build a much bigger business than if you just turned on ads for everyone.

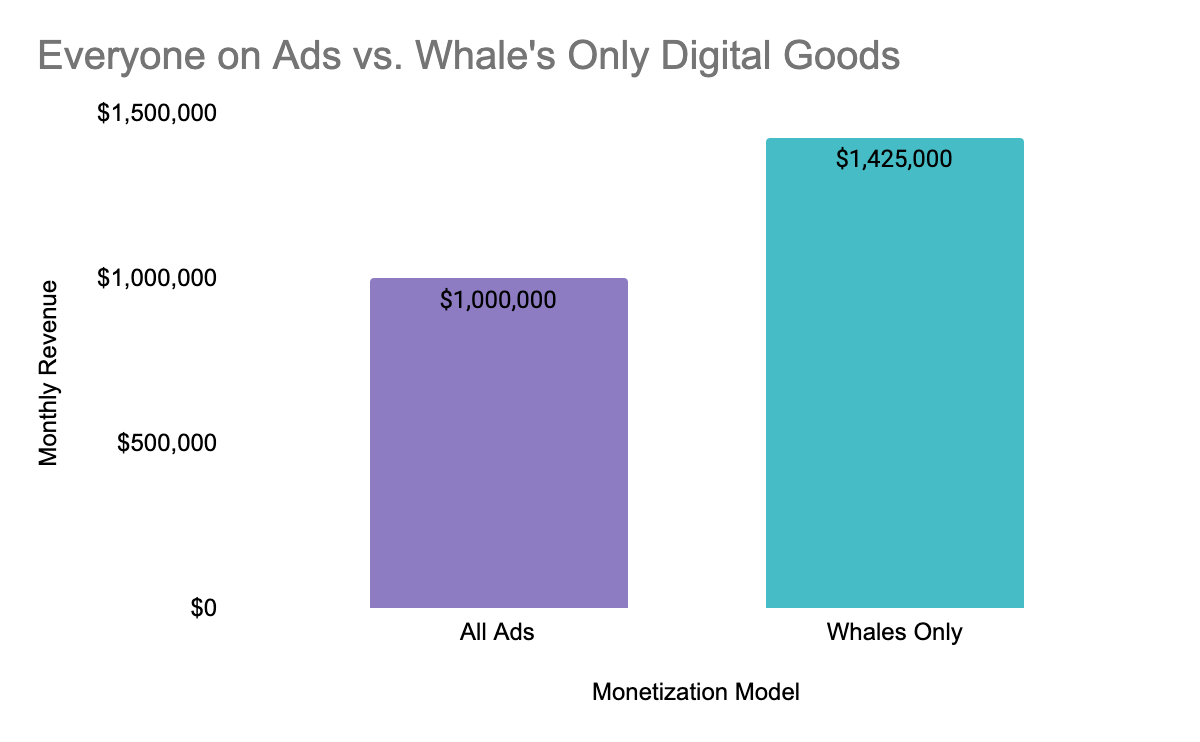

This holds true even if you drop my super whale percentage to .1%

Hopefully I don’t need to say this for you my beloved readers, but the business generating more cash tends to do better. You can reinvest it into additional marketing to bring on new users, or more likely, invest the cash into building new features that keep the whales happy and spending.

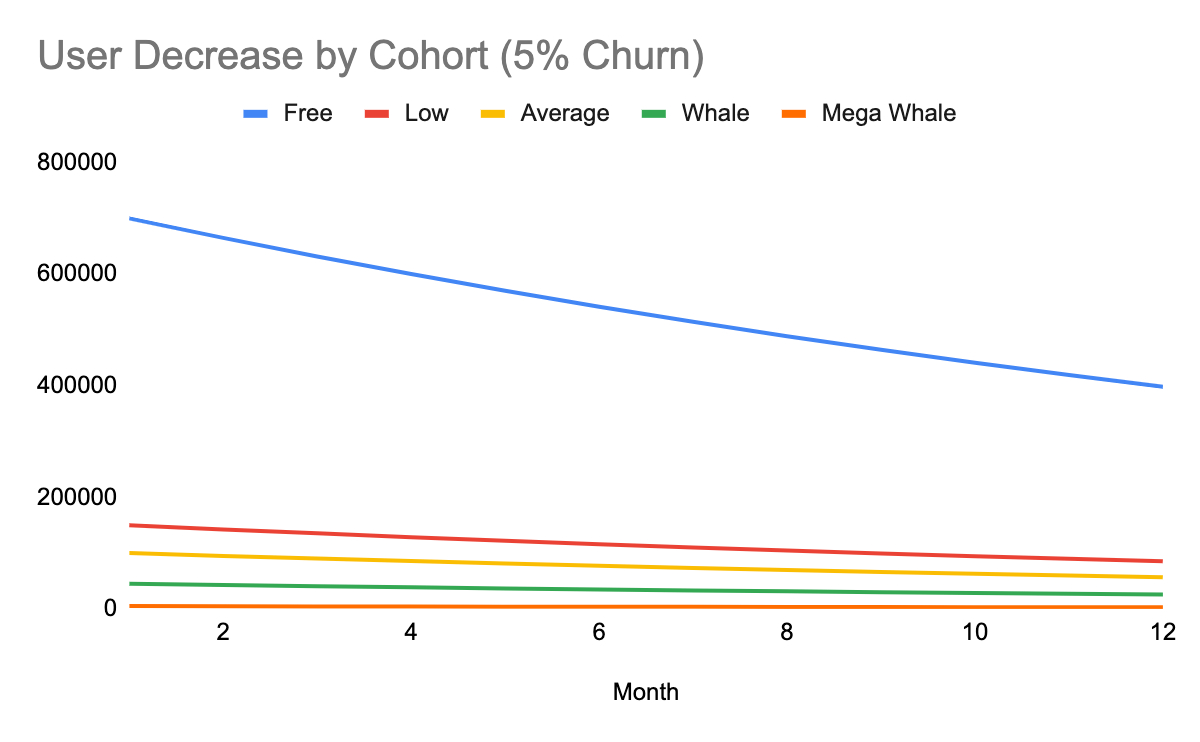

To illustrate why it is important to keep whales happy and in your game, let’s assume you have 5% of all your players churning every month. The user chart would look scary.

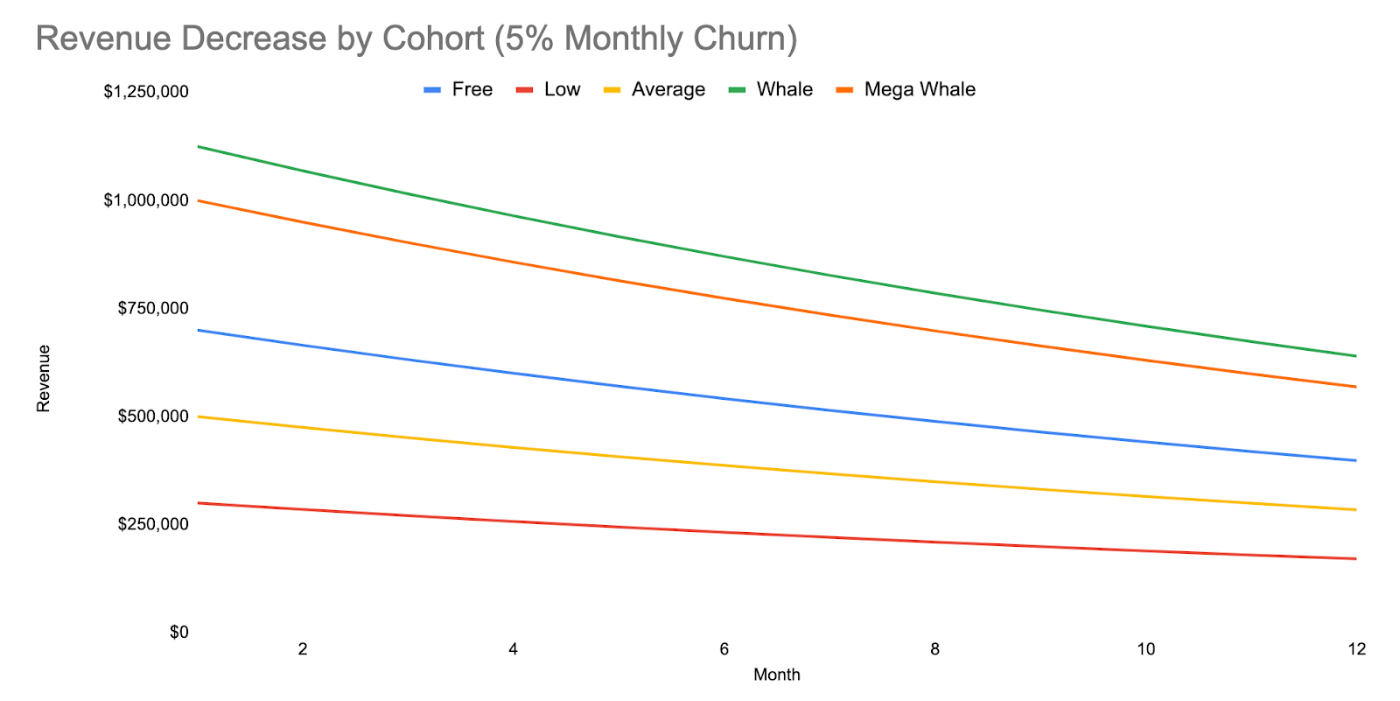

Put in contrast to revenue however, and the case for retaining whales becomes much more obvious.

In other words, for every Super Whale you lose, you would need to add 200 free users to make up for the revenue difference.

Note: One interesting thing I didn’t want to muck up the model with—after 3 months you will have lost >80% of your users. This churn I modeled above is actually a much more accelerated and chunky process. So activating payments and keeping people paying is a really crucial first step in the process.

This power-law dynamic holds true when you compare customer acquisition costs to their lifetime value. Assuming an equal ten-dollar acquisition cost across all cohorts (reasonable because all users have to start out as free) and a three-month lifespan, free users have a Lifetime Value/ Customer Acquisition Cost ratio of .3. In other words, you are spending a dollar and getting 30 cents back. For the whales, the LTV/CAC ratio is 75/10=7.5. You can’t possibly earn a profit by just acquiring the ad supported free customers.

In sum, the entire free-to-play model, from acquisition to revenue to churn, is reliant on upselling people for ever more digital goods. There is no reliable way out.

This is How They Get You

As I listened to my interviewer explain the case, I felt increasingly uncomfortable. In a market as ruthless as F2P gaming, competitive dynamics will reward those developers who are the most skillful and unscrupulous in the methods by which they keep people playing and paying. When I asked my interviewer if I was right with this guess, she wouldn’t quite meet my gaze—answer enough.

There are all sorts of nefarious tricks a developer can deploy to try to hook people. A few examples:

- Playing by Appointment: Games will timekeep certain events: “You can only get this reward by playing at 2pm tomorrow!” The player feels compelled to come back to the game.

- Pay to Skip: Developers will make a certain level basically unbeatable then allow you to spend money to skip it and move on. This one is beloved even by major players like Electronic Arts ($EA $40.7B Market Cap.)

- Pay to Win: Players can purchase power ups that will allow them to win battles or rewards that make them better than other players. Note: There are rumors of a Saudi player spending over a million dollars to accomplish this in Clash of Clans.

There are dozens of these dark patterns. If you are interested in learning more about the legality of these tactics, I recommend this incredibly thorough article from the University of Colorado Law Review (it is rare for me to recommend anything written by a lawyer so worth the click).

All of these techniques will be brought to bear against consumers. They are so complex and so fleeting, with various iterations slipping in and out of popularity, that regulation is incredibly complex and nearly impossible to get right.

Even when you ignore these tricks, there appears to be a naturally addictive element to video games. The best research I could find was a 6-year study of n=385 15-year-old boys. 10% of them showed signs of addiction with negative outcomes including, “higher levels of depression, aggression, shyness, problematic cell phone use, and anxiety than the non pathological group, even when controlling for initial levels of many of these variables.” While we can’t know for certain, it is likely that at least some of these whales are suffering from addictive behaviors towards video games. So while 90% of people were just fine playing video games, there was a significant percentage that struggled with addiction.

F2P companies are doing the rough equivalent of Bud Light setting up a bar at an AA meeting. While alcohol has done a lot more harm than video games (and I in no way want to trivialize the trials surrounding alcoholism) the comparison is apt. F2P business models rely on getting people well and truly hooked.

In Defense of These Companies

I want it to be clear—this isn’t the fault of the companies! It is the structure of the markets that is forcing these decisions. To win in the long-run, you have no choice but to monetize like these businesses do. There may be the occasional breakout game that bucks the trend, but they are the exception not the rule. The revenue model is an overwhelming center of gravity, slowly pulling all companies towards morally dubious product choices.

This is the defense almost all people will hide behind (myself included) when they hear their business did something that makes them feel queasy: some variant of “I need to provide for my family” or “our business employs hundreds of people.” This logic isn’t wrong. Jobs matter and it isn’t like these people chose to shape the market the way it is.

But the line between providing enjoyment and exploiting addiction is a thin one. Individuals who start and work at video game companies are presumably not going into the industry with the overt goal of addicting folks. All they want is for people to have a fun time and play their game. But because pretty much everyone instinctively wants to respect the whole “free will” and “individual choice” thing, companies will just default to a free market position. Companies will never be the ones to tell users if they are addicted. Plus, some percentage of these whales can easily afford all this superfluous spending. A free market default means you can kind of just let the chips fall where they may. Since the distinction between addiction and enjoyment is so tough to define, most companies will just stay as far away from that conversation as possible.

When governments do step in with regulation the results are, once again, morally complicated. In China, they have instituted time and monetary limits for players under 18. This in itself is probably fine, but to implement it, they built a state registration and person-tracking technology system. This is the same government that built a tracking system to commit genocide against Uighyer Muslims. Of course, these may be different technologies, and are certainly different branches of government, but nevertheless, it feels weird! The European Union has tried the opposite approach of trying to regulate how companies design their products (particularly in the case of gambling mechanics like loot boxes) but has been largely unsuccessful in this attempt.

If you abstract this out another layer, all companies/ organizations/ institutions/ products will hurt a certain percentage of the population. Facebook enabled many SMBs to survive the COVID pandemic with its advertising tools (good) but also helped instigate the January 6 Capital riots (bad). Goodwill helps employ people who may otherwise struggle to find jobs and upskills them to improve their careers (good) but sometimes their couches have bed bugs (bad). Juul helps people quit smoking (good) but got hundreds of thousands of teens addicted to nicotine (bad). These aren’t apples-to-apples comparisons, and the potential harm from Goodwill is a much easier pill to swallow than that of Juul, but the tradeoff is still there. F2P companies allow many people to find little moments of enjoyment throughout their day (good) but can addict and harm a percentage of their players (bad).

There really are no easy answers here.

The goal of Napkin Math is not to pontificate on ethical decisions or give moral direction, but they are important points to consider regardless. In practical application, you should honestly evaluate if your industry structure forces your company to make choices you find ethically dubious. If it does, do the following:

- For company founders: To permanently alter industry dynamics, you almost certainly have to radically change your monetization model and competitive approach. If you just try to play the same game as your peers but better, you’ll still be subject to the same forces

- For individual employees: Change industries and leave your employer in the dust. Or even better, come up with a whole new business model that allows for more equitable outcomes and put your former employer out of business :)

Is this easier said than done? Of course! But until people start making hard decisions, users remain at risk.

Til next week,

e

Read Trapital to gain insights from hip-hop culture

If you enjoy reading Napkin Math, check out Trapital. It's a weekly newsletter that will keep you ahead of the latest trends that start in hip-hop and impact the rest of the business world.

Hip-hop culture is home to some of the most influential business leaders. Trapital's founder Dan Runcie breaks it all down in a concise and engaging way. His essay on Will and Jada Pinkett Smith's content and commerce strategy is a great lens into the future of media.

Trapital has been featured in The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, BBC World News, NPR All Things Considered, and more. It's a go-to source for the industry's power players.

Join 10K+ subscribers who read Trapital and sign up here for free.