02 - MANA WĀHINE TOA - The Rise of the Fierce Wāhine Māori

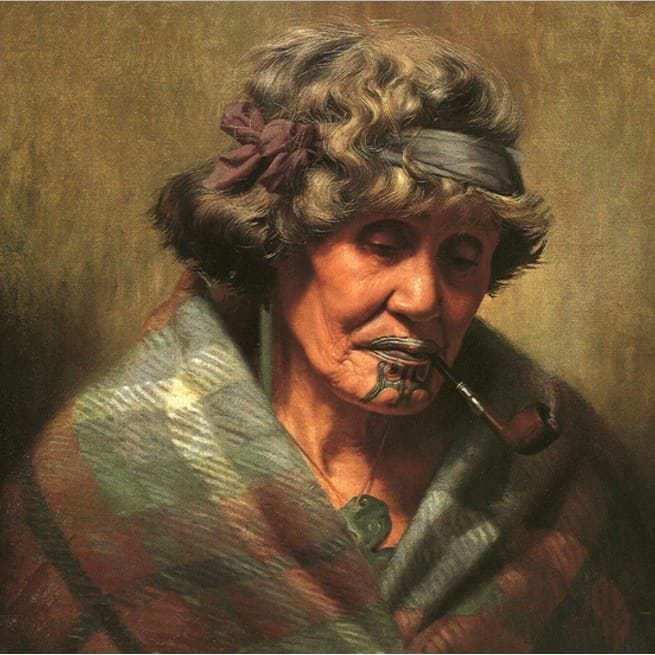

Today’s pickings 02 - MANA WĀHINE TOA - The Rise of the Fierce Wāhine MāoriThe gentle uprising of the ancient feminine lurking behind the shadows of the Mānuka treesDear Readers, Welcome to the second part of our journey inside Te Ao Māori (Māori world). Today we will look closer into the marks that the Polynesian women proudly wear. Also, we will meet their Melanesian cousins who are starting a fresh wave of the revival of their ancestral marks. Let's resume our journey from where we left it off and slowly move forward into the cultural revolution and its significance. To remain aligned to the context of the story, you can read the previous chapter here. Or start at the introduction here. The position of Māori women in an Aotearoa post-colonialismWhat is most devastating about the colonial past is that it never really came to an end. The past continued and permeates into the present. It rises like smokes and ghosts of a forgotten time inside the heart of ex-colonized civilization. Some people brush it off with indifference, while others desire to bring back the pre-colonialism era. Dreaming of a non-violated indigenous world is wishful thinking. It is also a denial of the existence of many people whose genealogies got mixed. It is like burning the rope at one end while hanging by another end. It doesn’t work that way. We are mired with the troubled past of colonialism of our nations and its influences on our lives. The ex-colonized citizens are a product of conditioning of centuries of colonization that penetrated and forcefully shaped the collective psyche of their people. Establishing the old values on our modern ideologies is the only way forward. It is a whole cycle of unlearning the recent past and re-learning the forgotten ones. Let us now discover how their colonial past conditioned the Māori women and how are they unshackling the old ways. The women of Aotearoa (New Zealand) have always played a crucial role in political protests against the rudimentary government policies. However, they were not included in policymaking for very long. The absence of women from decision-making or advisory roles set up by the crown is proof of the neglect of the Wāhine Māori. Post urbanization, the whanau structures slowly become more and more unstable, giving way to more nuclear family structures. The government dismissal of the wāhine and their need to find employment was apparent. As a result, several young women found themselves without any support in midst of an economic firestorm, without livelihoods, and often vulnerable to perpetrators both within the domain of home and outside. The attitude of law is deeply biased towards the wāhine. The highest number of women incarcerated in New Zealand belong to the Māori ethnic group. The pākehā values were at odds with the Māori values, and on speculations, one can say that the cultural dysphoria (in addition to the financial crisis) would have been at the root of all unlawful activities that they got involved with eventually. And this dissonance along with the shallow public understanding of the Māori people gave birth to the simplified stereotyped perceptions in popular culture. One such harrowing tale is depicted in a critically acclaimed film called “Once were Warrior”. The movie conveniently plays on stereotypes of urban Māori families ensnarled in a net of tragedy. The themes revolve around unemployment, alcoholism, crime, poverty, and domestic violence. Nothing about this movie is aesthetically pretty or visually compelling. It is a brutal and eye-opening tale of the harsh realities that many indigenous families face today in cities. However, I repeatedly ask myself - Is that it? Is that all the popular culture can reflect about the Māori people? Where are the stories of bravery, love, companionship, community, and belonging? Where are the stories of sacrifice and resilience? My question arises from an informed place of empathy and understanding of the mana that guides the Māori people and their actions. The stories of mana are where the philosophical gold mine is hidden. Weapon of warColonization was an act of war, and like any other war, it comes with sexual violence. The free-spirited and empowered Māori women were a threat to the crown. Wāhine Māori was spiritually significant within the whanau, hence they were specifically targeted by the intruders. The intention was to inflict humiliation on the whanau and break them morally, rendering them weak. Rape was used as a weapon to win the land wars. Since the cook’s crew landed, assault on indigenous women became a norm in the islands. Before performing such a hedonic act, they first dehumanized the indigenous women as barbaric, immodest, and befitting of such atrocity. Such sexualization of rape is not only silently locked way in the pandora’s box of history, it is reflected in media even today. Consider this instance, in 2011 when Ms. Daley died on a beach after being sexually assaulted by two non-Indigenous men, media reported as “Wild sex led to woman’s death”. Such use of language is abhorring and inexcusable. What was the emphasis on? Does it mean the victim was deserving of the violence inflicted on her? This casual acceptance of violence towards these women is an indicator of the social status of the wāhine today. Even in literature like in Kim Scott’s novel “Benang: From the Heart”, rape is used as a sub-plot to explain how sexual violence is intrinsic to other inhumane aspects of colonialization, like eugenics. The novel talks about a white man who thinks rape can be used to “breed out the color”. The tortured past of the Māori people is a sardonic tale of unaccountability displayed by the ex-colonizers, and the apathy practiced by their successors today. However, like the slow rising fury of their mother goddess Papatuanuku, the wāhine are now ready to wake and shake the aged structures of their colonial past. The Rippled connection arising in the sea and settling in the skinHumans have imitated nature for centuries, be it the scent of flowers or the strength of the wings. Our species has the innate ability to mimic and adapt within the frameworks of our natural world, further optimizing our imitations to perfection. Our ability to visually realize and explore through the lens of art gave birth to various languages. In our desperation to explain our myriad complexities and emotions, we invented symbols and visual cues. These symbols imitated the world of three dimensions into a two-dimensional format. The periodic repetition of these symbols forms meaning, thus forming language. Every symbol that exists today in the indigenous world contains the information and stories of their ancestors. The stories cannot be ignored because they are etched in a familiar language, the stories that bring back culture from its obscure fringes. Historically such stories have been hosted on a variety of canvases from cave walls, to stone tablets to hemp parchment. But the living surface that brought these stories to life is human skin. Polynesia, at present, is caught in a huge wave of a revival of the traditional ancestral skin markings brought about by the women. Let us move into this transformative journey of the gentler uprising of the spirit of the Wāhine Māori. And then we shall travel further to visit our sisters in Melanesia and see how their inspiration of revival is driving them. Tā moko (Aotearoa/ New Zealand)The origin story of Tā moko has a mythological influence. It is believed that the word ‘moko’ was derived from the name Rūaumoko. He was the unborn child of Ranginui (Father Sky) and Papatūānuku (Mother Earth). He remained inside the womb of Papatūānuku and was believed to be responsible for earthquakes and volcanic activities. His activities left nothing behind but destruction and scars on the terrains of land. This is the reason why the early forms of Moko were designed to be worn as a sign of mourning. It is a sign of transformation from joyful childishness to the wisdom that comes with the loss of a loved one. It is said that during the period of mourning women would haehae (lacerate) themselves using obsidian or shells and place soot in the wounds. Lacerating oneself was an expression of grief, and the pigment served as a reminder of the loss. Wearing a moko was like arresting oneself in scars that were left behind by life’s upheaval. Scarred and wise was more than just symbolism, it was a sacrificial practice of surrendering to pain. Moko kauae or the chin markings is a privilege reserved only for the Wāhine Māori. Getting permanent markings on your face demands a deeper commitment and a sense of security in who you are. According to prof Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, even today many people take moko as a form of healing. So many people connect back to their whakapapa to reclaim their identity while mustering their strength to go through a devastating life crisis. This includes but is not limited to recovering from physical and sexual abuse, miscarriage, hysterectomy, and loss of a parent or a child. The whanau women assemble in the marae (community hall) while singing the songs of their iwi and hapu and marking each other's bodies. They bleed together while recreating the experiences of their ancestors. The journey of taking the marks is the only practice that has kept the wāhine māori rooted at their spiritual center. After two centuries of oppression and obscurity, the wāhine are again covering their bodies in the ancestral marks to remind the world of who they are. It says something about the inextinguishable flame that these women carry within their spirits. The marks swirl & flow symmetrically in geometrical patterns, connecting the spirit to the body. Like how the ocean connects the islands in one meaningful unison. One can hear the ancestors whispering their presence through those sacred marks. In the traditional Māori worldview, the moko is an open gateway for your ancestors to communicate with you. It is an opportunity and responsibility of a lifetime to act with the wisdom of your whakapapa. With the onset of colonialism, women’s aesthetics were much controlled. Marking one's body was seen as blasphemy, unholy and distasteful. Women were discouraged and eventually punished for wearing a moko. They were denied jobs and education if they chose to wear their ancestral marks. It was not a mere cultural loss, it was banishment from participation in unity and celebration of the feminine body. It was arresting the identity of the wāhine in the limited definitions of womanhood constructed by the white patriarchal supremacist ideologies. Moko kauae is traditionally worn by women and given by women. When the practice of marking was prohibited, the circles of wāhine who shared joy, intimacy, and belonging within these small groups, were also taken away. They were separated from their sisters where they once felt understood and accepted for being themselves. Eventually, the women moko artists got entirely obliterated from history. Prof Ngahuia talks about a well-known gifted moko artist called Kuhukuhu Tamati. She famously inscribed many chiefs and their iwi in the upper north islands. And yet no one knows about her. Coincidence? I don’t think so. The intentional misplacement of history is a common strategy of suppression. Every Māori woman with a whakapapa has the right to wear the kauae as a mark of survival. As a display of resilience. As a reminder to the treaty partners that they are still present rising like the waves of the ocean, unshackled and complete in their identity, roaring in the silent language of symbols etched on their skin to claim back what was rightfully theirs. Māori inking techniquesMāori moko stands apart from other Polynesian markings because the technique and tools used to make a māori moko are different. The chisel called Uhi made out of bones of sea birds (Te Uhia Mataora), is used to make deeper grooved lines on the skin, much like carving a block of wood. Then a comb-like instrument is used to place pigments (charcoal from a resinous tree) into the skin. This process makes Māori marks unique. For now, the journey into New Zealand's Māori world ends here. Now we will take a small pause and step back to breathe in all that we have learned from them so far. Their story of re-inventing a new identity within the settler world is a story of awakening to the collective need of belonging. It is safe to say that the modern Māori people use wisdom and experience as their canoes to navigate their way further into the world. Tatau (Samoa)When we enter Samoa it is impossible to ignore the beautiful Samoan women who wear a range of different delicate designs on their legs from their upper thing till just below their knees. These Samoan marks are known as Malu. The term 'malu' refers to the idea of sheltering and protection. Women wore malu because it was a totem of protection cast on her by her ancestors, and which she would wear as a shield for the protection of her children and family. These markings are sometimes also worn on hands and lower abdomen - a sign of transition into womanhood from girlhood. As per the legend, the two siamese twin goddesses Taema and Tilafaiga who were the original matriarchs of Samoa, are the ones who brought with them the gift of tatau. One day they started to swim across the ocean and arrived at the island of Fiji, a long way from their home island Ta’u. In Fiji, Tufou, and Filelei, two women taught them the art of tattooing. They also taught them a song which they must sing when they mark someone. The song said that the tattoo is given by the women and worn by the women. However, when the twins reached the island of Samoa, seasick from their swimming across the pacific they meddled up the song. Now the tatau was worn by the men and not the women. Even with this rhetoric, the women still wear the marks because the Samoan men believe their women should stand equal to any man. They gave their women the freedom to etch their identity and strength on their skin. They believe that marks have protected their women during wars. It is because the Samoan malu can be instantly recognized by a Samoan warrior. Journey into MelanesiaTatu or vera vera (Papua New Guinea)

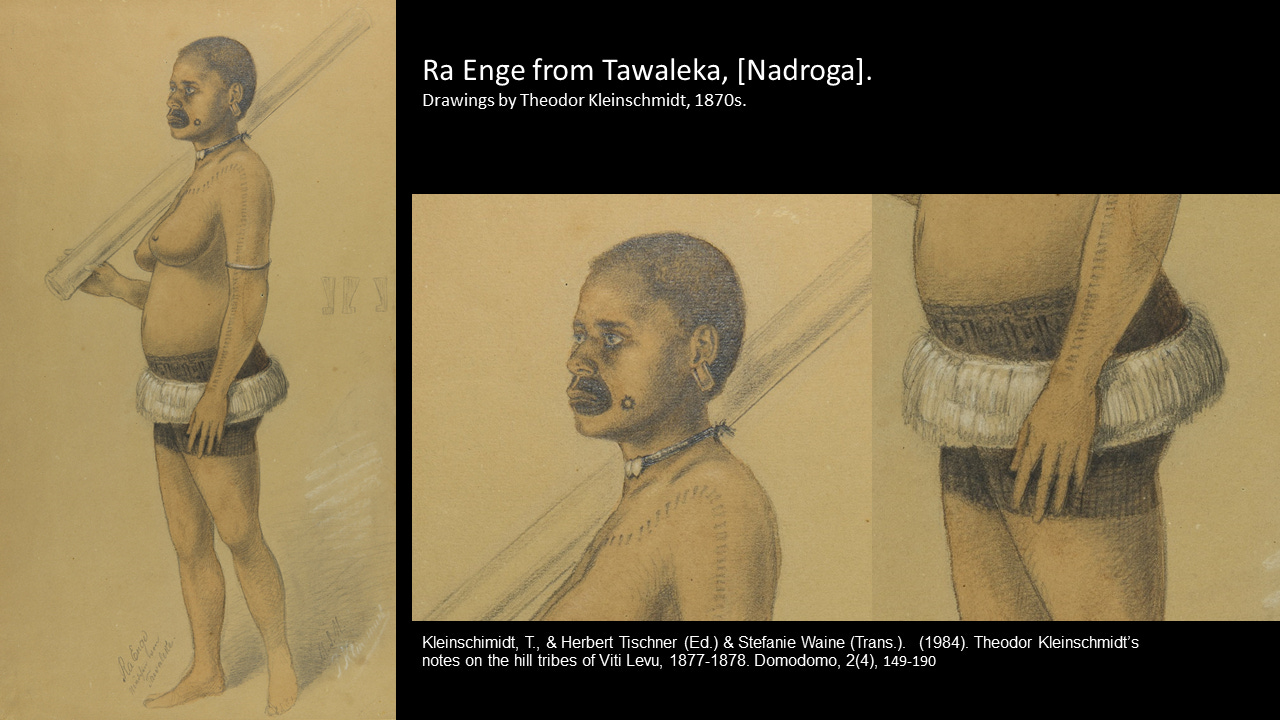

The fierce, high-spirited, and eloquent Julia Mage’au Gray is a visual artist, dancer, and skin marker of Papuan-Australian descent and the owner of Melanesian marks (a center of art and culture). With her contagious charm and yet serious manners, she describes her relationship with the art of marking skin. She says not everyone can wear a mark without understanding the importance of it. It has got something to do with your ancestry and family. The marks have to be chosen carefully because as per Malenisian beliefs the marks and the body should move in unison while dancing. An exclusively sensual and rewarding aspect of womanhood. In one of her journeys, Julia figured that the loss of marking of skin happened to Papua New Guinea in a very sudden and final manner. In her grandmother’s generation, everyone was marked head to toe and suddenly after that, no one was ever marked again. She said there were not even any questions about why that was so. It was understood that the missionaries were at the heart of all this. However, it was not so openly talked about among Melanesians as much as their Polynesian cousins do. Julia says in Papuan culture tatu is given only by women, both to men and women. The marks worn by women of Samoa and Tahiti have originated in Fiji (another island of Melanesia). There was a connection that got lost when the missionaries started to come to Fiji and Papua New Guinea. She believes that to revive what once was lost, one should pick the tools and bring history back. Ownership of one's legacy is the reflection of Julia's inspiring Papuan values. In her documentary Tep Tok, she embarks on this journey of revival. She reconnects to her roots, hoping to bring back the art of marking as a long-lost gift for her Melanesian sisters. The Papuan women were still a lot more fortunate. At least they have seen the ancestral marks on the skin of their bubus (grandmothers) unlike the Fijian people whose marking tools are now rusting in museums. The Fijians have completely lost touch with the art of skin marking and its relevance in the modern world. I think that is what Julia means when she says that the Melanesian marks have to be brought back from old to new old. Because without necessary modifications, the marks will lose their significance in the modern world. Fiji (Veiqia)Tarisi Sorovi-Vunidilo who studies lost art said veiqia was the Fijian term for tattooing and was a tradition in the olden days where a girl was tattooed on her torso and private parts to show she had reached puberty and was ready for marriage. Tarisi is trying to document the pride of the culture that was long lost in the early 20th century. The longer the colonization, the deeper its blow on culture. Hawaii (Kakau) and Batok Filipino tribal tattooThe last wave of revolution is emerging in the island of Micronesia - Hawaii, and the Philippines. The women are deriving inspiration from their Polynesian and Melanesian cousins. Whang Od, who is 92 years old, is the last Kalinga tattoo maker of the Philippines. She is now passing down the knowledge of marking skin to her granddaughter to keep the tradition alive. Announcement about more posts on Oceania:I am planning to release a detailed analysis of another beautiful Melanesian island called Vanuatu by December. This idea is inspired by my friend Nicola, who lives in a stunning eco-farm in Vanuatu, and her passion for history, culture, spiritual journey, and food. Nicola, who writes a deeply personal newsletter Surrender Now, talks about trauma and the essential process one must undertake to heal. Nicola's courage and gentle spirit have inspired me to look within my own mental patterns. Her deep voice throughout the narration of her journey indirectly insists that we make our choices consciously while owning our lives. In the future post about Vanuatu, Nicola will guide us through the journey inside her enchanted home, its people, food, history, and much more. Stay tuned for this exciting collaboration, and subscribe to her newsletter to know more about how the beautiful landscapes of Oceania inspire her to live a centered and mindful life. List to quench your knowledge thirst: Documentaries to watch to learn more about the visual art skin marking of Oceania: Videos to watch to understand more about the various performance art of the Māori culture:

|

Older messages

01 - MANA WĀHINE TOA - The Goddess, warriors, and Mothers

Saturday, September 25, 2021

Enter the world of Wāhine Māori, who were once born with Mana which was forcefully torn away from them

MANA WĀHINE TOA - A Prologue

Wednesday, September 22, 2021

Stories of the sacred warrior feminine from the islands of Oceania

The Nature of Creativity

Sunday, September 12, 2021

Thank you for being on this journey with me

Welcome to Berkana!

Tuesday, September 7, 2021

Thank you for signing up for Berkana

You Might Also Like

• Book Promo Super Package • FB Groups • Email Newsletter • Tweets • Pins

Wednesday, January 1, 2025

Newsletter & social media ads for books. Enable Images to See This "ContentMo is at the top of my promotions list because I always see a spike in sales when I run one of their promotions. The

BUMP doors closing

Tuesday, December 31, 2024

Super quick reminder → the Copywriting Course New Year's deal is going away tonight in a few hours… 50% off an entire year (Plus 2 extra months). That's 14 total months of training and

🤝 Why Smart Biz Buyers Love the Holidays

Tuesday, December 31, 2024

3 ways the holidays are your huge opportunity. Plus: 1 incredible biz buyer story Biz Buyers, Welcome to Main Street Minute — where we share some of the best stories and ideas from inside our

Reading Atomic Habits to start the new year? Here's a free bonus

Tuesday, December 31, 2024

Happy New Year! Let's kick off 2025 with some free bonuses. Atomic Habits is currently on sale for up to 49% off and many people are reading (or re-reading) the book to start the year. This was

eBook Giveaway • Enter for a Chance to Win !

Tuesday, December 31, 2024

eBook Giveaway from Tony Faso eBook Giveaway Enter to win via King Sumo! Hi there, Exciting news!

Six Art World Predictions for 2025

Tuesday, December 31, 2024

Your weekly 5-minute read with timeless ideas on art and creativity intersecting with business and life͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

The Kids' TV Host Who Was Put in Time Out

Tuesday, December 31, 2024

Why you shouldn't make people work on holidays?

🧙♂️ Let's burn the "brand deal rules" in 2025

Tuesday, December 31, 2024

Because those "rules" are costing you thousands... ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

200+ New Years Goals

Tuesday, December 31, 2024

We asked what people plan to do in 2025, here were the most common answers: Here's the detailed list of goals: In 2025 most people wanted to build: #1.) Build or scale a business #2.)

For Authors: Audio Book Promos 🔊 Tweets & FB group posts • 60 Day orders save 15% +

Tuesday, December 31, 2024

Affordable Audio Book Promos See what authors are saying about ContentMo Enable Images Audiobook