Net Interest - Big Tech Does Finance

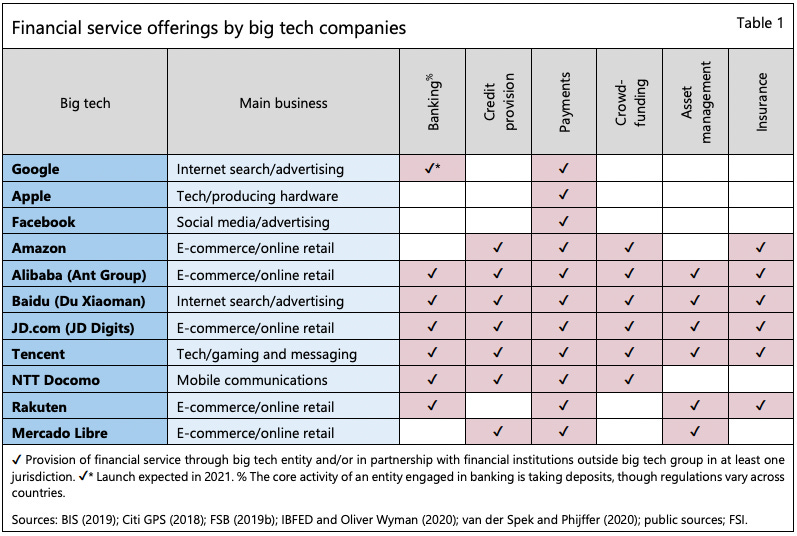

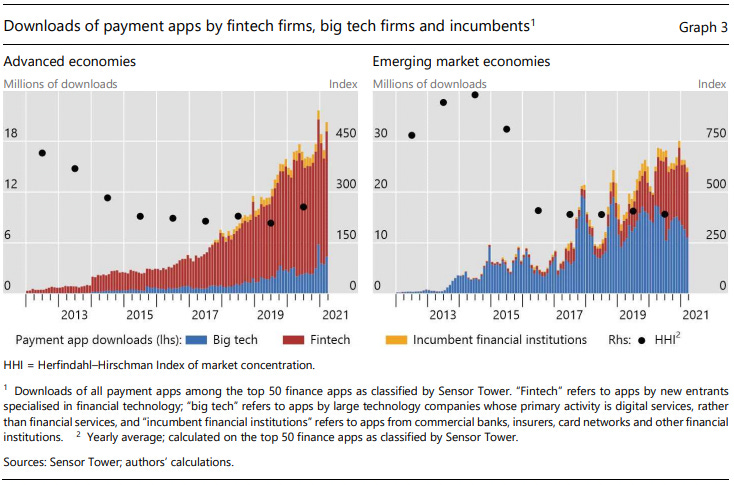

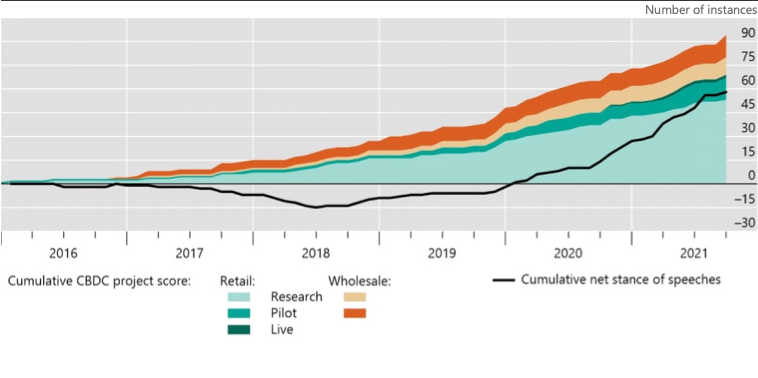

This is a free version of Net Interest, my newsletter on financial sector themes. For additional content and supplementary features, please consider signing up as a paid subscriber. One company has dominated headlines this week: Facebook. First its systems went down and then a former product manager, Frances Haugen, testified in Congress at a Senate hearing on consumer protection. Haugen highlighted problems at Facebook and called for greater regulatory oversight. “The severity of this crisis demands that we break out of previous regulatory frames.” It didn’t attract as much media attention but the next day, four thousand miles away, in the Swiss town of Basel, financial regulators met to discuss how their own regulatory frames might be applied to Facebook and other big tech companies. Facebook isn’t a financial company, at least not yet. Back in 2019, Mark Zuckerberg articulated grand plans to become one via a cryptocurrency called Libra. “What we’re trying to do with Libra,” he told lawmakers, “[is] rethink what a modern infrastructure for the financial system would be if you started it today rather than fifty years ago on a lot of outdated systems.” We talked about Libra in Facebook's Big Diem, earlier this year. Zuckerberg’s proposal provoked a backlash from policymakers around the world and the company was forced to dial back its aims. In May, it abandoned plans to seek a stand-alone license in Switzerland and retrenched back to the US in a much diluted structure. But that hasn’t stopped Facebook from tackling financial services from other angles. In India, it launched a payments service via WhatsApp last November, after two years of regulatory roadblocks and data compliance issues. WhatsApp has 400 million users in India, which the company anticipates it can convert to payments customers. So far it’s been slow going; its market share as of September is only 0.01%. In Brazil, Facebook added payments functionality to WhatsApp in March, after a false start nine months earlier, when the central bank made it stand down over fair competition and privacy concerns. WhatsApp has 120 million users in Brazil, so again the upside from converting existing customers is high. Yet in the downtime between its false start and finally going live, the central bank rolled out its own payments settlement platform, PIX, which has been gaining traction since. Facebook hasn’t released market share data for WhatsApp Pay in Brazil, but Visa has said that the volume of transactions processed over the platform via Visa debit cards grew by 78% between the first and last weeks of May, so it looks promising. Last month, I launched a paid version of Net Interest and the response has been amazing. As well as the free feature piece, subscribers get supplementary comment on breaking themes, invitations to conference calls and access to a full searchable archive. To join, sign up here:Among large technology companies, Facebook isn’t alone in its ambitions to enter financial services. In India, Google is a market leader in payments, with a 35% market share of digital payments conducted over the government’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI). It also has a European payments license, received in December 2018. Although Google recently scrapped plans to launch a bank account in the US, it remains committed to payments, where Google Pay has 25 million users in the US. Amazon offers a range of financial services across its markets globally, including Amazon Pay, various credit cards, Amazon Cash and Amazon Lending. In India, it offers auto insurance directly from its app, in partnership with a startup insurance underwriter in which it is an investor. Around the world, big tech companies accounted for $700 billion of credit in 2020, up 40% on the prior year, according to data from the Bank for International Settlements. This data includes China, where as well as originating credit, big tech companies have a strong franchise in payments (94% market share in mobile). The reason large technology companies are attracted to financial services is simple. They have large installed customer bases, powerful brands, access to capital markets and superior information about customer preferences and habits, all of which have the potential to be leveraged into financial services. The advantage of superior information is especially key. In the past, many areas of financial services, including lending and insurance, were hampered by problems of adverse selection. A fraudulent borrower knows in advance he’s never going to pay back that loan, but he’s able to hide that intention from the bank. Access to lots of data changes this notion of asymmetric information. While the borrower has multiple attributes and knows most of them, the platform harnessing data can better gauge how these attributes interact. The classic example is the motorist who likes red cars. What he may not know – but his insurance company does – is that drivers of red cars are statistically more accident prone. With more and more data available to platforms, a growing amount of risk information can be inferred, shifting the information advantage away from the customer towards the provider. Much of this data comes from payments transactions. Payments used to be an ancillary service of financial services companies. Banks were at the top of the hierarchy, with payments further down, dependent on banks’ central role. But payments are a high frequency means to gain insight into a consumer’s financial behaviour. Ant Group harnessed this advantage in China and added a lending business on top of its core payments business, Alipay. In fact, it went a step further, incentivising borrowers to stay current on their loans with the threat that their payments functionality would be hampered in the event of default. Ant Group’s credit losses have remained lower than industry averages. The competitive threat from large technology companies has long left banks anxious. On his full year 2019 earnings call, founder, CEO and chairman of Capital One, Rich Fairbank said: “Often we’re asked by investors about fintechs and what about this start-up and that start-up. And of course, we keep an eye on that. I think the sort of elephant in the room is the gigantic tech companies and the sort of opportunities that they have.” Other bank CEOs have complained about the playing field being tipped against them in favour of the large tech companies. Ana Botín, executive chairman of Santander, said as much in an op-ed in the Financial Times in January. Jamie Dimon, CEO and chairman of JPMorgan returns to the theme regularly, and will likely do so again next week when JPMorgan reports third quarter earnings. Financial regulators are getting anxious too, hence the jamboree in Basel, Switzerland. Although the big tech footprint in financial services is currently relatively small, regulators are aware that the market can shift very rapidly. Having watched big tech companies amass significant power over the past ten years in other fields, they know that the longer they wait, the harder it can be to untangle. Better to lay down some rules now before it gets too late. As one policymaker said, big tech companies can migrate from too-small-to-care to too-big-to-ignore to too-big-to-fail very quickly. Policymakers have three alternatives. First, they could continue to apply existing financial regulation, competition and data rules to big tech companies. Many authorities employ the principle that the same activities should be subject to the same rules, which is why they require tech companies to get a payments license if they want to offer payments or a credit license if they want to offer credit. But this does not reflect the interplay between activities. In addition, existing regulatory frameworks leave gaps in oversight. Most of the oversight of big tech so far has come from competition authorities and data privacy authorities, with financial regulators taking a back seat role. Yet, as one regulator pointed out, financial regulators and competition authorities hardly speak to each other. A particular gap has emerged in the oversight of cloud service providers. Financial institutions are increasingly reliant on these services but their regulators don’t have authority over them. There have been some noises to designate cloud service providers ‘systemically important financial market utilities’ alongside other financial market infrastructure assets like exchanges and the DTCC but that hasn’t yet happened. The second alternative is to introduce new rules, adapted to the new environment. This is what the Chinese authorities have done. Yi Gang, Governor of the People’s Bank of China told the audience in Basel about China’s experience with regulating big tech companies. Despite the benefits the likes of Alipay and WeChat Pay have brought to the economy, he highlights five drawbacks ranging from cross-sharing of data within platforms to diversion of deposits away from banks. As a result, Chinese authorities have implemented new rules. Platforms now have to register as financial holding companies, separating their financial business from tech services; and, in the case of Ant Group, personal credit information has to be opened up to the whole market and not kept private. The final tool regulators have at their disposal is to go into competition with the big tech companies, by setting up public utilities. This is what authorities have done in India (with the Unified Payments Interface) and in Brazil (with PIX). It’s also the motivation behind central banks around the world pushing forward with central bank digital currencies – discussed here last year in The Politics of Money. Right now, central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are live in only two regions: the Bahamas and the Eastern Caribbean states. But pilots have been completed in a number of other countries and policymakers’ narrative is getting more positive. Whether big tech companies outside China are successful in breaking into financial services in a major way is moot. The point is that financial regulators think they might. And having been disappointed by what they’ve seen competition authorities accomplish, they are ready to get involved. That could mean more public financial infrastructure like central bank digital currencies. If that’s the case, then Facebook’s legacy in financial services may be less what it does itself and more what it provokes governments into doing. For further reading on financial services regulation, read my earlier post, The Policy Triangle, which looks at the trade-offs financial regulators face. This week’s subscriber-only section is bigger than usual. It examines what it takes to be a good analyst, looks at how some fintech companies have facilitated fraud on a major scale and whether gamification of stock trading is so unusual. To read it, sign up here.I was a guest on Bilal Hafeez’s MacroHive podcast this week. We discussed financial crises, bank valuations, fintech, the evolution of credit, why private equity firms have institutionalised better than hedge funds, the state of sell-side research and more. You can listen here or via your regular podcast platform. You’re on the free list for Net Interest. For the full experience, become a paying subscriber. |

Older messages

No Time to Die: China Banks Edition

Friday, October 1, 2021

The Story Behind the World's Largest Bank

Price Comparison Websites: Go Compare

Friday, September 24, 2021

The Squeezed Middle Between Google and Product Providers

Banking the Poor

Friday, September 17, 2021

Lending Without Collateral

M-Pesa and the African Fintech Revolution

Friday, September 10, 2021

A Mobile Operator's Foray into Financial Services

Next Steps for Net Interest

Friday, September 3, 2021

Introducing a paid tier

You Might Also Like

Longreads + Open Thread

Saturday, March 8, 2025

Personal Essays, Lies, Popes, GPT-4.5, Banks, Buy-and-Hold, Advanced Portfolio Management, Trade, Karp Longreads + Open Thread By Byrne Hobart • 8 Mar 2025 View in browser View in browser Longreads

💸 A $24 billion grocery haul

Friday, March 7, 2025

Walgreens landed in a shopping basket, crypto investors felt pranked by the president, and a burger made of skin | Finimize Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March 8th in 3:11 minutes.

The financial toll of a divorce can be devastating

Friday, March 7, 2025

Here are some options to get back on track ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Too Big To Fail?

Friday, March 7, 2025

Revisiting Millennium and Multi-Manager Hedge Funds ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

The tell-tale signs the crash of a lifetime is near

Friday, March 7, 2025

Message from Harry Dent ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

👀 DeepSeek 2.0

Thursday, March 6, 2025

Alibaba's AI competitor, Europe's rate cut, and loads of instant noodles | Finimize TOGETHER WITH Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March 7th in 3:07 minutes. Investors rewarded

Crypto Politics: Strategy or Play? - Issue #515

Thursday, March 6, 2025

FTW Crypto: Trump's crypto plan fuels market surges—is it real policy or just strategy? Decentralization may be the only way forward. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

What can 40 years of data on vacancy advertising costs tell us about labour market equilibrium?

Thursday, March 6, 2025

Michal Stelmach, James Kensett and Philip Schnattinger Economists frequently use the vacancies to unemployment (V/U) ratio to measure labour market tightness. Analysis of the labour market during the

🇺🇸 Make America rich again

Wednesday, March 5, 2025

The US president stood by tariffs, China revealed ambitious plans, and the startup fighting fast fashion's ugly side | Finimize TOGETHER WITH Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March

Are you prepared for Social Security’s uncertain future?

Wednesday, March 5, 2025

Investing in gold with AHG could help stabilize your retirement ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏