When historians write the story of the rise of the Creator Economy, there are two moments, ten years apart, that are guaranteed to appear. The first, in Spring 2007, is when YouTube started sharing advertising revenue with creators—a decision that arguably laid the foundation for the “Creator Economy” as we know it today. The second, in Spring 2017, is when the cracks in that foundation became impossible to ignore, and questions about the legitimacy of the platform economy started to emerge.

Spring 2017 marks what is now popularly known among creators as “Adpocalypse.” YouTube faced a mass exodus of advertisers due to concerns about their ads being featured next to objectionable content. The platform overhauled its advertising policy, and thousands of creators saw their views and earnings plummet as a result—some by as much as 99%.

“Literally almost everyone across the board has seen their views cut in half,” one creator told New York magazine at the time. “So we’re trying to fight the Not Advertiser-Friendly system as well as fighting the new algorithm, and it’s, like, how are people supposed to live off this anymore, you know?”

For many YouTube creators, Adpocalypse was a wake-up call. It was the first time they realized that their revenue—in some cases, their entire livelihood—came with strings attached. It was the first time that creators questioned the legitimacy of the bargain that they’d made with the platform.

But it wouldn’t be the last. The first Adpocalypse in 2017 was followed by Adpocalypses two, three, and four in 2018 and 2019. And YouTube isn’t the only platform to have faced tension with its creators. In 2016, Facebook faced pushback after it made changes to Instagram’s algorithmic feed that impacted creators’ engagement on the platform. When OnlyFans announced changes to its content policy in summer 2021, the backlash from creators was so immediate, the platform was forced to suspend the changes almost immediately.

If this pattern sounds familiar—a collective of individuals balks at the policies that govern them, and demands better terms from the powers that set those policies—that’s not an accident. What are changes to platform monetization policies but a form of taxation without representation? What are creators if not a new category of labor, not unlike platform gig workers or factory workers from before, seeking protections for an emerging type of work that had previously never existed?

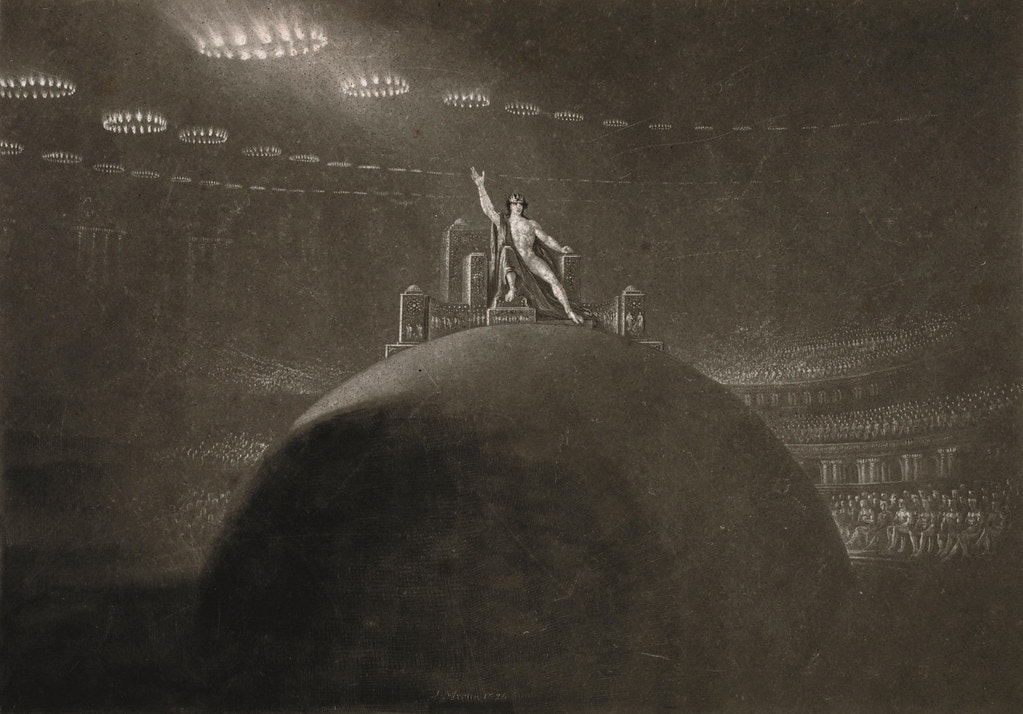

Like feudalism and divine right monarchy before it, the creator economy (at least, in its current, highly centralized form) is experiencing a legitimacy crisis. Creators are questioning the terms that govern their relationship with the platforms they frequent—and the right of the platforms to set those terms in the first place. How the ecosystem responds—what alternatives are proposed, who builds them, and how—will shape the next phase of the Creator Economy.

What is legitimacy, and where does it come from?

Legitimacy is one of those things, like air quality, that we often don’t think about until something seems off. We all participate with various political, economic, and social institutions—governments, schools, workplaces—that govern our behavior. When we think those systems are fair, we believe they're legitimate. When we think they're unfair and we deserve a better deal, we believe they're illegitimate. Vitalik Buterin, the co-founder of Ethereum, wrote that “Legitimacy is a pattern of higher-order acceptance.” When enough people within the system question the system’s fairness it threatens the system's ability to continue to function, and you get a legitimacy crisis.

The term “legitimation crisis” was coined by sociologist Jurgen Habermas in the 1970s. But philosophers and social thinkers have been thinking about legitimacy—who has it, where it comes from, how it’s lost—for centuries.

It was the ancient philosopher Aristotle, for example, who posited that political legitimacy rests on the “legitimacy of rewards”—that, under a just system, everyone receives benefits in accordance with their virtues. Two thousand years later, political philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued that a government’s legitimacy is dependent on the general will and common interest (as opposed to the interests of the individual, like a monarch or small elite.) A century after Rousseau, German sociologist Max Weber theorized three basic sources that legitimacy can come from:

- Traditional legitimacy—essentially, rule by status quo. “Follow me, because it’s always been done this way.”

- Charismatic legitimacy—in other words, rule by cult of personality. “Follow me, because I’m charming and compelling.” (The rise to power of many autocratic leaders follows this pattern.)

- Rational-legal legitimacy— in other words, rule by rationality. “Follow me, because the system of rules and laws I’ve built are clear and objectively make society run better.”

Ultimately, legitimacy derives from trust: trust that the governing order is just, trust that agents establishing and enforcing that order are doing so in the interest of the greater good. Legitimacy crises happen when that trust is eroded—when the governed no longer believe that those in power are exercising that power with the collective good in mind.

The concept of legitimacy is not restricted to political institutions. Economic systems and powers can have and lose legitimacy as well. For example, feudalism lost legitimacy as an economic system in Europe when laborers—rendered scarce and therefore valuable by the devastation of the Black Plague—gained greater bargaining power and leveraged that power to secure greater personal autonomy and (eventually) greater economic freedom, which eventually led to urbanization and the creation of the merchant class. The Industrial Revolution and the Gilded Age that followed resulted in a legitimacy crisis between factories and their workers, as workers demanded better working conditions—and child labor laws, the weekend, and the American middle class were born as a result.

Our understandings of legitimacy and where it comes from are subject to change. In fact, shifts in conceptions of legitimacy are often the impetus for legitimacy crises: four hundred years ago, people took it more or less for granted that a government’s legitimacy was believed to come from the divine birthright of the monarch; then, the concept of “the consent of the governed” rose to popularity during the Enlightenment, and democracy replaced monarchy as the one legitimate governmental structure in much of the world.

All of this brings us to the current conflict in the platform economy. Increasingly, creators no longer trust that platforms are making decisions with an eye toward the collective good, or that the outcome of the platforms’ decisions will result in all participants receiving fair rewards.

The thing is, that wasn’t always the case. Not so long ago, the legitimacy of the platforms—their status at the center of the creator and attention economies, their roles as primary mediators of commerce in the 21st century—was largely unchallenged. Knowing how the platforms gained that legitimacy—and how they lost it—is important to understanding what will need to happen in order for the crisis to be resolved.

How the platforms gained legitimacy—and then lost it

Originally, the platforms all derived their legitimacy from Weber’s three sources listed above: charismatic, traditional, and rational-legal.

In the earliest days, their legitimacy was largely charismatic: founders like Mark Zuckerberg and Jeff Bezos built auras around themselves as technological geniuses and philosopher kings by painting compelling visions of the future their creations would make possible. There’s a strong traditional bent to platform legitimacy as well. Platforms are free to build and manage their products as they see fit because they are private companies, usually with founder control of their boards, and traditionally, the right of private companies to build and manage their domains as they see fit has gone unchallenged.

Mostly, however, the platforms have sought to build their legitimacy through rational-legal means—legitimacy through a system of rules and laws that everyone understands and agrees to. Through terms of service and content moderation policies, “objective” algorithms and “unbiased” oversight boards, the builders of the platforms have constructed what amounts to their own legal systems—essentially nation-states unto themselves. These systems are built to protect everyone, and maintain the best possible community for all.

But over time, the faults in the social contract between platforms and creators started to show. Policy changes like those implemented during Adpocalypse revealed the extent to which the platforms’ policies and practices are designed to protect and advance the interests of the platform—regardless of their impact on creators. Algorithms can be tweaked to either give traffic or take it away depending on what keeps viewers engaged and ad revenue flowing. Data ownership policies lock creators and their audiences in, keeping the platform positioned as mediator and moderator of the relationship for a fee that the platforms have a unilateral right to determine.

The result is a dynamic in which platforms exercise near-autocratic control over the creators that frequent their platforms. YouTube can demonetize high-profile creators at will. TikTok can ban its biggest stars indefinitely. Apple determines who gets to live in its App Store, and OnlyFans can dictate the morality of their creators to appease their payment partners and investors.

As creators have started to identify and gain recognition as a distinct category—as skilled professionals, as craftspeople, as partners who provide value to the platforms they frequent—they’re increasingly asking themselves questions about the fiefdoms under which they work, and coming to the conclusion that the system is not set up in their favor. Each subsequent monetization change or policy failure further strains creators’ trust in the platforms—not unlike the series of parliamentary acts that culminated in the Declaration of Independence in colonial America.

Which brings us up to today, and to the current state of the social contract between platforms, creators, and the platform ecosystem as a whole. Today, the legitimacy of platforms rests, to a large degree, on a traditional justification—arguably the most fragile of the three, and the most susceptible to misuse. Platforms make their own rules and, by extension, set the terms of the creator economy because that’s how it’s always been done, and because no one has put forward alternatives that can meaningfully replace the status quo.

Fortunately, that’s starting to change.

How the legitimacy crisis in the creator economy ends

There are two ways that a legitimacy crisis can resolve itself: either the regime re-establishes legitimacy by realigning their rule with the interests and norms of the community (as factories in the Industrial era did by instituting fairer work policies); or, the system is overthrown, and a new one is put in place that better aligns the values and incentives between people and the nexus of power.

The platforms have made efforts to regain legitimacy with creators via the first route, by increasing the variety of monetization avenues available through their platforms. Twitter and YouTube have both added tipping functions to their sites. Facebook recently announced plans to pay $1B in “bonuses” to creators through 2022. But these efforts at realignment reveal the extent to which the platforms are either unable or unwilling to truly change the terms of their relationship with creators. For example, Facebook’s bonuses will only be available to select creators, and will be tethered to certain “milestones” that are likely aligned with product and growth goals that Facebook has set.

It seems clear that if there is going to be a resolution to the legitimacy crisis in the platform economy, it is going to come in the form of the second option: the emergence of genuine, credible challengers to the platforms that offer a more democratic, decentralized alternative to the platform economy as it is currently constructed.

The first generation of these companies is already on the scene. Products like Patreon, Cameo and Substack have gained traction over the past several years by zeroing in on the monetization component of the problem, offering creators pathways to generating revenue directly from their audiences rather than relying solely on platform-controlled advertising revenue.

But as we’ve seen, monetization is only one dimension to the platform legitimacy crisis. It’s not just about money: it’s about agency and autonomy, and having the opportunity to participate in decisions that directly impact your livelihood. It’s about breaking the unilateral power that platforms hold as centralized points of control in the ecosystem.

Fortunately, many of the innovations being pursued by founders building in Web3 are aimed at introducing exactly the kind of corrections that the platform ecosystem needs to resolve the current crisis. There are three areas in particular where founders looking to power the next generation of the platform economy should focus their efforts: ownership and portability of data, participatory decision making and cooperative business models, and decentralization via crypto and open-source protocols.

Ownership and portability of data

One of the most significant sources of conflict in the current platform economy is the way the data is controlled and mediated. Platforms own the data created on their platform—including identities, content, interactions, and engagement—which, by extension, puts them in control of the creators’ relationships to their audiences. Creators are essentially captive under this model, unable to leave a platform without leaving their audience and their business along with it.

An important step to realigning the social contract in the platform economy will be to change this dynamic, and give creators the ability to own and transfer the data associated with their business.

Next-generation platforms have already begun shifting to more data-portable models. Substack, for example, gives writers total ownership over their audiences and allows them to take their email list of subscribers with them if they ever decide to leave the platform; furthermore, writers use their own Stripe account, which means subscription relationships aren’t tied to Substack as a platform. Creators are also increasingly moving into building their own independent properties, monetizing their audience directly via tools like Stripe and Venmo.

In contrast to the current closed paradigm of building consumer platforms, decentralized networks (cryptonetworks) are built on open data (stored on public blockchains), enabling users to have transparency and control over what is happening. For instance, creators can mint NFTs and sell them across a number of different platforms, and no single marketplace “owns” that NFT. This dynamic means that creators can operate outside of specific platforms, and can move to other networks and services that better align with their needs and values. True creator consent, and legitimacy, occurs when creators are able to participate in systems from a place of freedom of choice rather than data-driven lock-in.

Decentralized building via open-source development

Open source protocols played a critical role in developing much of the early infrastructure of the web, including email. Over time, open-source was largely crowded out by a more proprietary mode, as companies built centralized networks that far exceeded the capabilities of open source protocols (compare Facebook to email). As the current legitimacy crisis resolves itself, and the platform economy recorrects toward a more democratic, representative model, open source protocols could play a central role again.

The proprietary product development of the platforms is a major reason they’re able to maintain control over their ecosystems. Platform owners and internal teams decide what features are developed, what integrations are available, who they are available to and on what terms, and creators are forced to accept those terms if they want to participate on that platform. This, in turn, results in features that create lock-in and prioritize platform profitability over creator autonomy and empowerment.

With open-source development, this dynamic could be disrupted. Instead of features being chosen based on what has the potential to unlock more ad revenue or keep users from leaving the platform, features would be chosen based on what makes the most sense for the community as a whole.

Participatory decision-making and cooperative business models

I’ve written before that I believe that true creator empowerment goes beyond data ownership. In a platform economy that was truly built to empower creators, the creators would own the platforms themselves.

From this standpoint, crypto tokens represent one of the most promising innovations for enabling ownership to be distributed and transferred on the internet as easily as information.

Crypto networks are decentralized networks that utilize crypto tokens to incentivize and reward participation; Bitcoin and Ethereum are early examples of crypto networks that were bootstrapped by rewarding participants with their native tokens, which represent ownership in the network. Decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) are online communities that are owned and operated by their members, via a token. I’ve previously compared DAOs to “crypto-native cooperatives.” In DAOs, decisions about the direction of the community are made by their members. One can imagine a future in which decisions about monetization, algorithmic prioritization, and other decisions that platforms have historically made unilaterally would instead be made by creators and users themselves.

One example of this model in action is the crypto-native publishing platform Mirror. On Mirror, a $WRITE token will allow users to become a member of the Mirror DAO, which will collectively determine how to allocate the treasury and product evolution.

While crypto tokens offer the strongest form of distributing ownership to the community, smaller-scale outcomes can be achieved by inviting creators into the business as shareholders or advisors, which would also give creators the opportunity to participate actively in the decisions that impact the business, and better align incentives between creators and platforms. One example of this is Airbnb’s Host Advisory Board, composed of 18 hosts who regularly convene with company leadership.

Towards a brighter future for the platform economy

When I first became interested in the Passion Economy several years ago, what drew me to it was the way that platforms seemed to promise a new, more individualized, more autonomous pathway to earning a livelihood, outside the traditional workplace. The more time I’ve spent in the ecosystem, talking with creators and observing the dynamics between them and the platforms they utilize, the more I’ve come to realize that there’s still work to be done to deliver on that promise. The platform economy as it is currently constituted—highly centralized, highly mediated, with critical decisions made by a select few—risks replicating the same problems that have led to widespread burnout, financial precarity, and erosion of workers’ rights in the traditional economy.

Throughout history, legitimacy crises have often resolved into new, more representative forms of governance. That is the opportunity I see in the platform economy today. It’s not a foregone conclusion, however: like all change, the outcome is contingent on who takes the lead and the choices they make. But if the next generation of networks can optimize for creator ownership and autonomy and more representative decision-making, we will be that much closer to realizing the promise of a truly liberated future of work.