18. On the influence of journalism in Albert Camus’ development as an intellectual and writer

18. On the influence of journalism in Albert Camus’ development as an intellectual and writerOr, how criticism of the media informed the writing of The Plague

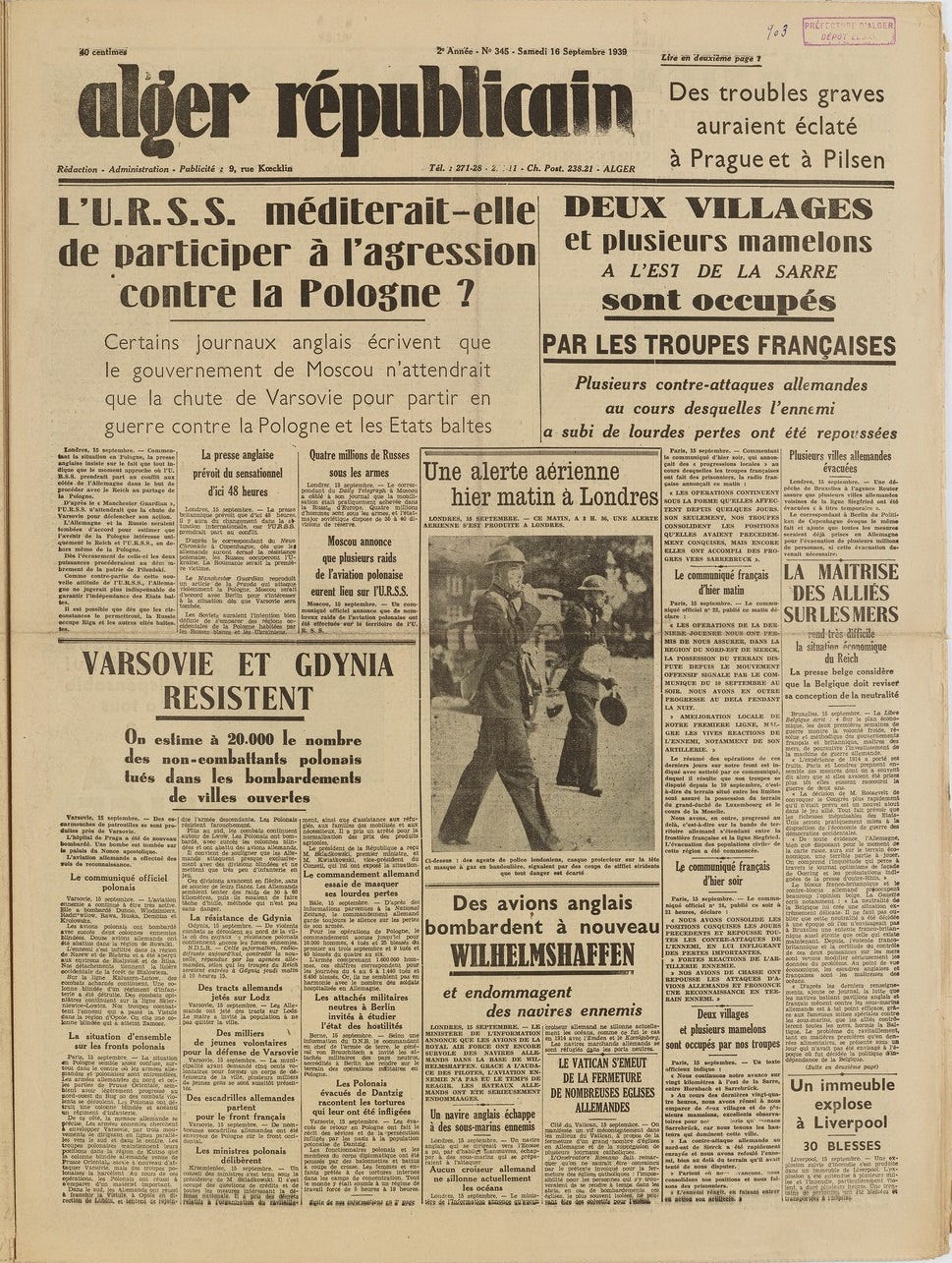

1. Albert Camus had an ambivalent relationship with journalism and the press. Circumstances led him, almost by accident, into the profession in the first place – his tuberculosis – and circumstances – tuberculosis and war – led him to very quickly be given more responsibility within the newspapers he worked for in Algeria (as we noted previously). But there was another variable at play, and that was Camus’ friendship with Pascal Pia, a figure ten years his senior. It was Pia who hired Camus for Alger Républicain in 1938, within days of Camus being rejected for certification to become a school teacher. And it was Pia who promoted Camus to editor-in-chief of Le Soir Républicain in 1939, when many of the staff were conscripted into the war. Pia also arranged for Camus the job as layout editor for Paris-Soir when he was blacklisted in Algeria after the shuttering of Le Soir Républicain. Then, in 1943, it was Pia once more who brought Camus to Paris and put him to work at Combat. Without Pia’s intervention at each of these moments of personal need, it is unlikely that Camus would have pursued a career in journalism. But Camus did want to be a writer. He had his first collection of lyrical essays published by the time he started work at Alger Républicain, as well as having worked as theatre director. He had even started drafting his first attempt at a novel. Camus also wanted to be an intellectual, and it is this, perhaps more than anything, that accounts for much of Camus’ ambivalence toward journalism. At one level, Camus carried into journalism standards that he also applied to his understanding of the role of intellectual, and he tried to make journalism fit these requirements. In 1936, two years before he first turned to journalism, he wrote in his notebooks: ‘An intellectual? Yes. And never deny it. An intellectual is someone whose mind watches itself.’ This was a discipline he later applied also to journalism, defining a journalist as a mind that judges itself daily. ‘A journalist who does not judge himself daily,’ Camus wrote in Combat, ‘is not worthy of this profession.’ Like an intellectual, a journalist should also have the capacity to develop and evaluate ideas. ‘What is a journalist?’ Camus wrote: ‘He is first of all a person who is supposed to have ideas.’ Camus also used the standards of journalism to help clarify his own role as an intellectual and writer. He was drawn to certain aspects of journalism as a craft of writing: the daily discipline, the preference for concrete over abstract language, the need to hew closely to factual reality. This also encouraged him, in his thinking, to begin with daily political realities and to develop from this ideas regarding politics generally, rather than starting with a preconceived political philosophy and, in the course of trying to account for daily political realities, to slip into omission, distortion, and misinterpretation, otherwise characteristic of partisan political discourse. Although Camus was already predisposed toward thinking critically in this way, it was these aspects of the job of journalist that, in practice, arguably made Camus a better writer and intellectual. 2. Camus would use his daily editorials to test ideas which he would later develop into more non-journalistic pieces of writing. For example, in 1939 (or early 1940) Camus drafted a literary piece, in the form of a letter, regarding the onset of the war, articulating an individual response and attitude toward the situation. “A letter to a man in despair” – which, in many respects, is the model for his later series of “Letters to a German Friend”, written and published clandestinely during his period of exile in France – pulls together and reworks several ideas which he first developed in editorials over the previous two years, from both Alger Républicain and Le Soir Républicain, including the censored editorial already referred to at length already, where he outlined he ideas pertaining to clarity, refusal, irony, and obstinacy. In that editorial, for example, Camus argued against despair. In this literary epistle he explains why and how one should overcome despair. In the editorial he argued against submitting oneself to any notion of inevitability. Then, in this letter, he writes:

In the editorial, the flipside of this is that everything made by human beings can be undone by human beings, including war. ‘In the world of our experience, everything can be avoided,’ Camus wrote. ‘War itself, which is a human phenomenon, can be avoided or stopped at any moment by human means.’ This idea is developed further in his letter:

In the editorial, he writes:

While in the literary letter, this ‘sphere’ is developed into a ‘zone of influence’, from which an individual can carve out a field of possible action:

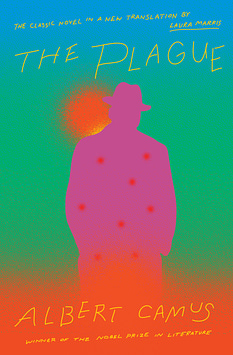

It is this ‘sphere’, this ‘zone of influence’, that after the war, while working on The Plague and The Rebel, became the ‘circle of flesh’ within which Camus argued that one must think and act, and beyond which one stumbles into abstraction and nihilism. The Plague, in particular, described not some universal framework or movement of History, but particular individuals thinking and acting within a particular circle of flesh, within their own zone of influence. 3. For Camus, particularly through the mid-1940s when he worked at Combat, he advocated for a hybrid form of intellectual journalism that brought together ideas and the everyday, morality and politics. The press, he argued, was responsible for creating a moral and political community, one in which ‘politics and morality are interdependent.’ This ideal was perhaps doomed from the start, even in the late 1930s in Algeria, when he first started developing these ideas, but it became more obvious to Camus himself in France in the mid-1940s that the vagaries of journalism were unable to fit the requirements of an intellectual. In practice, the constraints on journalism – the limited time, the lack of critical distance, the paucity of documents to compare and analyse – far outweighed any ethical corrective a journalist may provide their readers, from which a critical reception could be encouraged. ‘The conditions under which journalists operate do not always lend themselves to deep thought,’ Camus wrote in Combat in September 1945. ‘Journalists do what they can, and if they inevitably fail, at least they can toss a few ideas into the air for others to develop into more efficient instruments.’ The difficulty for Camus came from when these ‘more efficient instruments’, which writers and intellectuals may have developed more fully elsewhere, become, in the hands of journalists reporting on them, or reviewing them, or interviewing them, once more reverted into blunt tools. Camus learned this soon after having his own books published in 1942, when he first became the object of journalism, rather than its agent. He made it a general rule not to respond publicly to the specific reactions of others to his published books. This is a rule which he stuck to – with only a couple of notable exceptions – for the rest of his career. He did, however, vent in his notebooks. For example, regarding a review of The Stranger, he wrote: ‘Concerning criticism. Three years to make a book, five lines to ridicule it, and the quotations wrong.’ What justifies this, beyond the usual response from a disgruntled writer at receiving a poor review, is the final clause: ‘...and the quotations wrong... and it consequently serves as a basis for illegitimate deductions.’ The bare minimum required for reading a work – is to actually read the work. Misquoting a work, and then basing deductions upon the misquotation, is an indication that the reader has not only probably not read the work, but worse, has imported into it their own preconceived notions, making of the work a Procrustean bed upon which the reader has lost consciousness during the very act in which they should otherwise have remained attentive. Camus tried to voice these concerns publicly in 1950, in his essay “The Enigma”, albeit trying to soften the criticism through the use of irony. ‘A writer writes to a great extent to be read,’ he stated, adding in parenthesis: ‘(let’s admire those who say they don’t, but not believe them).’ And then:

4. One of the images that Camus is probably referring to here is of himself as ‘an existentialist’, something which can only be applied to him by those have not read his works with any degree of attention. He did, however, in an editorial in Combat, in early November 1945 attempt to push back on this assumption, which had already been gaining some traction in the press. ‘I do not much relish the all too celebrated existential philosophy,’ he wrote, ‘and, to be blunt, I find its conclusions false.’ In an interview, published only a few weeks later, he repeated this claim: ‘No, I am not an existentialist,’ he said, later adding, in the same interview: ‘the only book of ideas that I have published, The Myth of Sisyphus, was directed against the so-called existentialist philosophers.’ This is, of course, true. One of the central arguments in that work was against what he referred to as ‘philosophical suicide’. It was a criticism he levelled explicitly against existential philosophy. ‘I am taking the liberty at this point of calling the existential attitude philosophical suicide,’ he wrote there. This criticism was aimed at what he called ‘the leap’, which attempted to evade the consequences of the absurd experience by retreating into conceptual illusion. In Sisyphus he variously referred to this intellectual manoeuvre as the ‘existential leap’, or ‘that leap that characterizes all existential thought’, while the acceptance and perpetuation of such illusion was described as the ‘existential consent’. This argument and criticism was associated with the other main theme of Sisyphus, which developed into a criticism of hope. ‘As I see once more,’ Camus wrote there, ‘existential thought in this regard (and contrary to current opinion) is steeped in a vast hope.’ And yet, Camus’ position in that work was for rebellion instead of consent, to resist the leap, to live without illusion, and to not seek escape via some philosophical doctrine, preferring instead the possibilities of literary discourse. ‘Now, to limit myself to existential philosophies,’ he wrote in Sisyphus, ‘I see that all of them without exception suggest escape.’ He chose otherwise. But many preferred, and still prefer, ‘the image a hurried journalist has given of him’, as he wrote in “The Enigma”, which has ensured that he has received ‘that final consecration which consists of not being read.’ Camus’ criticism of existential philosophy also formed the basis of his underlying argument in The Rebel. His position there, against historicism – ‘Analysis of rebellion leads at least to the suspicion that, contrary to the postulates of contemporary thought, a human nature does exist, as the Greeks believed’ – runs counter to what was at that time being put forth by the modern variant of existentialism. As Camus stated in his notebooks, in 1946, during his trip to America, soon after presenting his lecture, “The Human Crisis”: ‘The idea of messianism at the base of all fanaticism. Messianism against man. Greek thought is not historical. The values are pre-existant. Against modern existentialism’ (emphasis in original). At the same time, as news of his work was belatedly appearing in the English language press, in the United States and Britain, it was under the growing shadow of ‘existentialism’, the latest fashion coming out of France. John Brown, reporting from Paris for The New York Times, wrote an article about Camus in April 1946, a few days before the publication of The Stranger in English translation. He understood the argument from Sisyphus which distinguished Camus from the existentialists, wondering only if Camus could resist forever the temptation toward intellectual suicide: ‘Will he end in finding a faith, in taking what is for him the unjustified “leap” into some form of hope, mystical or rational, for which he reproaches the Existentialists?’ Charles Poore, reviewing the novel a few days later (“Books of the Times: A Story of Pre-War Algiers”, The New York Times, Apr 11, 1946), cites Brown’s article, and also manages to read the novel without reference to existentialism. Likewise, a review from The Washington Post, published a few days after that (B.W. Rogers, “Ignoring Fate Won’t Make It Pass You By: The Stranger, by Albert Camus”, Apr 14, 1946). But a reviewer from The Tribune in England, a couple of months later, marks the turning tide in reception of the novel in English. ‘Were it not that existentialism, and the new French literary movement influenced by it, are now in the height of intellectual fashion,’ wrote Roy Fuller on June 28, ‘I am not sure that one would consider The Outsider as more than a very readable and unusual novelette with a sharp and individual flavour.’ He then makes a rhetorical move that was to become commonplace, which is to acknowledge Camus’ stated refusal to be classified as an existentialist, to ignore completely his reasons for doing so – which would require actually reading his books – and then to suggest that it doesn’t really matter and, for all that, he can be classified as an existentialist after all. ‘Whether its author is or is not of the existentialists proper can be left for nice discussion in those highbrow periodicals of this country and America suffering from existentialists...’ One Quixotic soul, in one of those highbrow periodicals in the United States, did try to resolve the issue later that same year. ‘Albert Camus has been nominated by a great many critics to the position of major disciple of the existentialist doctrine of despair,’ wrote Albert J. George, from Syracuse University, in the journal, Symposium, on November 1, ‘but, despite their efforts to lump him in with the faithful, he has several times loudly denied any adherence to this philosophy.’ George then cites these various denials, already quoted previously, which he not only accepts, but he follows up with by finding corroboration in Camus own works. ‘Le Mythe de Sisyphe not only contains an attack on existentialism,’ he writes, ‘but it holds the key to Camus’s other work, particularly L’Etranger.’ After showing how Camus references existential philosophers in Sisyphus only in order to show how they have committed intellectual suicide, George shows that he fully understands the sharp implications of Camus’ arguments in that work:

But it was too late. ‘Buy The Stranger by Albert Camus – the first of a series of Existentialist books to be published by Knopf,’ touted Eric Bentley in an article in Books Abroad, in Summer 1946. ‘You are safe too in ignoring Camus’ assertion that he is not an Existentialist,’ Bentley states. ‘After all, Karl Marx said he was not a Marxist.’ To be fair, for the majority of English readers, Camus’ own ideas were not directly available. The Myth of Sisyphus would not be published in an English translation until 1955, nearly a decade after Camus’ visit to the United States. So readers were overly dependent on ‘the image a hurried journalist has given of him’ during this initial period, coupled now with the inviolable force of a book marketing category; but at the same time, commentators were often dependent on each other, the same formulas and phrases and inaccuracies often being carried over from one article to another, one review to the next, amplified in the process, and becoming settled convention. A final rescue attempt was made, in June 1947, in a letter to the editor of the Wall Street Journal, when Marcel Aubrey, a representative of Gallimard in the United States, wrote to clarify a few points in a recent article about France and existentialism. One of the points being: ‘Albert Camus repeatedly and formally emphasized that he did not adhere to “existentialism”.’ But it was in vain. So enduring has this media image of Camus as an existentialist and a philosopher been that not only did it dog him for the remainder of his short life, but in the decades since his death it has only proliferated, along with other false images of his work, infiltrating beyond the journalistic and becoming canonised in academic courses and monographs. In this way, blunt tools have become polished, but remain blunt. 5. And this is largely why Camus had an ambivalent relationship with journalism and the press. This ambivalence made its way into The Plague. In terms of communications technology, the newspapers are singled out in the novel as being actively associated with the spread of disinformation. When the narrator sought to describe the general mood of the township, he did so by showing their growing dependence on the press and the corrupting effect this had upon them.

As one exchange shows:

It is here that the narrator showed how the township, giving in to their fears, sought escape in prophecies of old and the works of soothsayers. Many of these were serialised in the newspapers, whose justification, presumably, was that they were simply giving the public what it wants. ‘When history itself ran short of prophecies, they commissioned them from journalists, who, on this point at least, proved to be just as competent as their counterparts from previous centuries.’ The narrator added: ‘The other similarity between all these prophecies was that they were, in the end, reassuring. Except the plague was not.’ Elsewhere, the narrator used the disjunction between the press images of the situation with accounts given by figures such as Tarrou, in order to provide a point and counterpoint, between abstraction and concrete forces, in the narrative.

These ‘orders’ were given to the press from the administration, which, along with the first sermon of Father Paneloux, is structured within the narrative as being once more an enactment of the forces of abstraction which work to keep people from facing the reality of their given situation. The movement from abstraction to concrete rebellion in the novel is shown, in part, by the development of the character of Rambert, the journalist. We first meet this figure when he introduces himself to Rieux, telling the doctor that he initially came to Oran from Paris in order to report on the sanitary conditions afforded the Arab population.

Later, however, Rambert abandons hope of escaping from the town, and, after joining the public health squad led by Tarrou, he gives himself fully to the struggle against the plague. Throughout the novel, Rambert is contrasted to Rieux. The purpose of this becomes clear when we discover at the end that Riuex is also the narrator, for at the beginning of the chronicle he makes a few observations – ‘the commentary and precautions of language’ – regarding the nature of his written chronicle. This establishes the standards by which the chronicle is composed, but it is also by these standards that within the narrative, the role of journalism and the press is often criticised as falling short. First, the narrator states the limits of his role as chronicler: ‘His [the narrator’s] task is simply to say, “This happened,” once he knows that this did, in fact, happen, that it mattered to the lives of a whole population, and that there are, as a result, thousands of witnesses who will assess, in their hearts, the truth of what he says.’ Second, he claims, for purposes which he later elaborates, that he will keep his identity hidden through the course of his chronicle. And third, he describes the three kinds of sources which he draws upon in the composition of his work: ‘first of all what he witnessed, then what others witnessed, since, through his role, he ended up collecting the secrets of everyone involved in this chronicle, and last, the texts which finally fell into his hands. He plans to draw on them when the time seems right and to use them as he likes.’ Here he is referring to the fictional archive of materials which Camus originally intended to be inserted into the novel: newspaper reports, government papers and orders, private letters, diary entries, and telegrams. In many respects, in the figure of the chronicler Camus resolves the tensions he noticed elsewhere between the role of the intellectual and the role of the journalist. In 1939, in his suppressed editorial for Le Soir Républicain, Camus wrote, on the topic of refusal: ‘A free newspaper can be assessed by what it says but also equally by what it doesn’t say.’ It was one of those rules that Camus applied also to his literary fiction, in the form of restraint. Throughout The Plague, whenever Rambert made an appearance, before he submitted to the task before him, and joined the public health squads, the narrator always referred to him as ‘the journalist’; that is, up until the point that he finally chose to stay in the town and fight the plague. From that point on, the appellation of ‘the journalist’ is conspicuously dropped by the narrator, and, for the remainder of the novel, Rambert is only ever referred to by his name. Coincidentally, in June 1947, Camus himself committed an exemplary act of refusal by resigning from Combat entirely, because of an encroachment of moneyed and party interests, which threatened the independence of the newspaper, and, in turn, his own intellectual independence. That same month, The Plague was published. Next week we will outline Camus’ thinking regarding literary discourse, during the period of writing The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus, in preparation for how this influenced his writing of The Plague. If you appreciate reading this newsletter, and you want it to continue, then please consider doing one of two things, or both: please consider signing up to this newsletter (or updating to a paid subscription). And please share this newsletter far and wide, to attract more readers, and possibly more subscribers, to ensure that it continues.

You’re a free subscriber to Public Things Newsletter. For the full experience, become a paid subscriber. |

Older messages

17. On Albert Camus’ rules for journalism in dark and oppressive times

Monday, November 29, 2021

Or, how working as a journalist influenced Camus' development as an intellectual and writer

16. On the themes of language and communication in The Plague

Monday, November 22, 2021

And the underlying influence of technology in the spread of nihilism and abstraction

On the restoration of communication as a form of rebellion in Albert Camus’ thought

Monday, November 15, 2021

Or, how the play The Misunderstanding (1944) was a rehearsal for The Plague (1947)

14. On the transposition of The Myth of Sisyphus into an argument about language

Monday, November 8, 2021

Or, the influence of Brice Parain's philosophy of expression on Albert Camus

13. On the resistance to nihilism, abstraction, and ideology in The Plague

Monday, November 1, 2021

Or, how Albert Camus' novel implicates us all

You Might Also Like

Red Hot And Red

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

What Do You Think You're Looking At? #204 ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

What to Watch For in Trump's Abnormal, Authoritarian Address to Congress

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

Trump gives the speech amidst mounting political challenges and sinking poll numbers ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

“Becoming a Poet,” by Susan Browne

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

I was five, / lying facedown on my bed ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Pass the fries

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

— Check out what we Skimm'd for you today March 4, 2025 Subscribe Read in browser But first: what our editors were obsessed with in February Update location or View forecast Quote of the Day "

Kendall Jenner's Sheer Oscars After-Party Gown Stole The Night

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

A perfect risqué fashion moment. The Zoe Report Daily The Zoe Report 3.3.2025 Now that award show season has come to an end, it's time to look back at the red carpet trends, especially from last

The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because it Contains an ED Drug

Monday, March 3, 2025

View in Browser Men's Health SHOP MVP EXCLUSIVES SUBSCRIBE The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because It Contains an ED Drug The FDA Just Issued a Recall on a Supplement — Because It

10 Ways You're Damaging Your House Without Realizing It

Monday, March 3, 2025

Lenovo Is Showing off Quirky Laptop Prototypes. Don't cause trouble for yourself. Not displaying correctly? View this newsletter online. TODAY'S FEATURED STORY 10 Ways You're Damaging Your

There Is Only One Aimee Lou Wood

Monday, March 3, 2025

Today in style, self, culture, and power. The Cut March 3, 2025 ENCOUNTER There Is Only One Aimee Lou Wood A Sex Education fan favorite, she's now breaking into Hollywood on The White Lotus. Get

Kylie's Bedazzled Bra, Doja Cat's Diamond Naked Dress, & Other Oscars Looks

Monday, March 3, 2025

Plus, meet the women choosing petty revenge, your daily horoscope, and more. Mar. 3, 2025 Bustle Daily Rise Above? These Proudly Petty Women Would Rather Fight Back PAYBACK Rise Above? These Proudly

The World’s 50 Best Restaurants is launching a new list

Monday, March 3, 2025

A gunman opened fire into an NYC bar