This is a free preview of a subscribers-only post.

Today’s post is a collaboration between Every and The Diff.

Where Netflix Is

The Netflix Model Today

There is perhaps no more colossal waste of human potential than Netflix. An algorithmic content feeding tube, designed by Silicon Valley engineers to deposit dopamine into our lizard brains at the exact point that we would churn, Netflix’s final form will be a pair of wires shoved directly into our eyeballs giving us personally crafted reality television. I love it. Its service is paid for by over 222M viewers (with millions more gleefully pirating the content like they are Limewire in 2005). The stock price has been one of the highest performing of the last 20 years. It has single-handedly sparked a television and film creative renaissance.

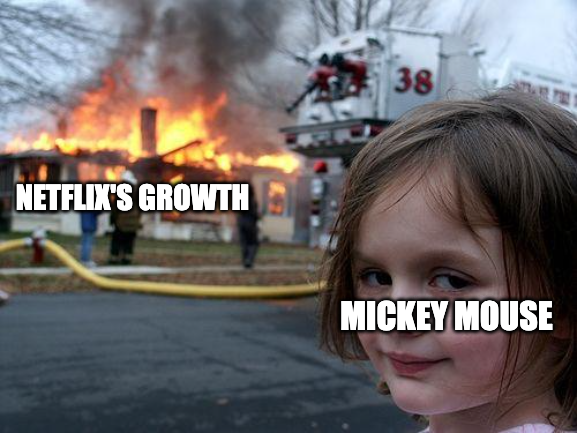

Whenever a new technology enables a fresh media paradigm, companies initially compete on an axis of distribution. The first televisions were distributed to American consumers with few channels. Media companies produced relatively bland and benign materials. News programs largely consisted of someone reading the headlines while smoking a cigarette. Howdy Doody held dominance in American children's consciousness for over 10 years just by being in color. Over time, as companies grow more comfortable with a new technology/medium, the bar for content quality is raised. Competition shifts from being able to use a technology to being able to use it effectively. Howdy Doody, despite being the first program to embrace color TV, was slayed by The Mickey Mouse Club.

Whether you view Netflix as a humanities catastrophe or entertainment’s pinnacle, there is no denying that it is an incredibly impressive business. By making streaming the dominant form of premium video consumption, Netflix embraced a new technology that catapulted them to the top of the world. Now the axis of competition has shifted to the second phase. Numerous companies have (mostly) figured out how to stream successfully. Their competitors are 10 times their size, have hundreds of billions of dry powder ready to deploy, and are willing to pay to win. This question is especially potent now—Netflix has missed on forecasted subscriber growth and has seen its stock price drop by 40%+ since November. Meanwhile, their rodentesque competitor Disney+ added 12M subscribers just last quarter. Whether Netflix is the winner of the future or is killed by Disney just as Howdy Doody was, is the subject of this essay.

CAC and LTV: How Auteurs Collaborate With Quants

Like any subscription company, Netflix lives and dies by one core calculation: the cost of customer acquisition relative to the lifetime value of a customer. Unfortunately for analysts, this number is incredibly hard to calculate even internally—and Netflix doesn’t release some of the data you’d want in order to measure it, even at a high level.

A shorthand approach to the LTV/CAC equation is to treat a company’s product and overhead costs as fairly fixed, and to look at the marketing costs to acquire an incremental customer, and then calculate a) the annual gross profit from that customer, and b) how likely the customer is to quit the service.

That’s always a fuzzy approach, because the cost of product development isn’t constant; companies do get operating leverage, but tend to increase their R&D expenses right along with sales. (In fact, for other subscription-based companies like Salesforce and Spotify, annual growth in R&D spending is higher than revenue growth; as the product matures, it takes more and more effort to build new features that will capture incremental customers.)

For Netflix, this equation is particularly complicated because their biggest cost, acquiring content, is also the lever that moves both user acquisition and retention. The company has had counterintuitive user acquisition and retention drivers for a long, long time; this dynamic actually predates their streaming business.

Back in 1999, when Netflix was still a DVD-by-mail company, one of their theories was that faster delivery would pay off because it would improve customer retention. When they started, customers in San Jose got their DVDs right away, while customers in, say, Florida had a longer wait. So the company did an experiment, and started dropping off DVDs at the Sacramento post office, too, to see if that would increase retention.

It didn’t.

To unlock the rest of the post (over 4K words of analysis!) please subscribe. Your first two weeks are free :)