Net Interest - PayPal, 20 Years On

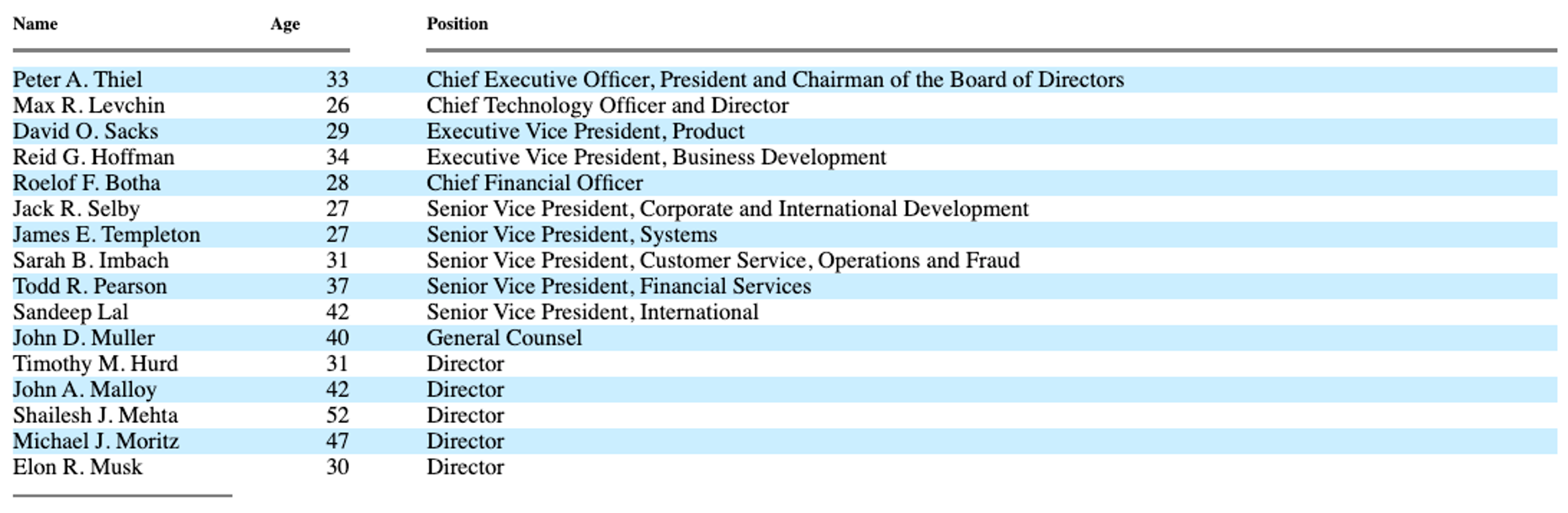

Welcome to another issue of Net Interest, my newsletter on financial sector themes. As a free subscriber, you get access to a weekly feature piece, this week on PayPal. But if you want to support my work and enjoy supplemental comment alongside some of the world’s top investors, then please sign up as a paid subscriber. Thank you! This week marks the twentieth anniversary of PayPal’s initial listing on the NASDAQ stock exchange. The company didn’t survive long on the public markets; it was acquired by eBay just five months after its stock market debut. But it left its mark. PayPal was around to offer online payments at the birth of ecommerce and has continued to grow as ecommerce has grown. At IPO, the company was valued at $790 million; today, even after having halved since its pandemic peak last summer, its market cap is over 150 times that. More than anything else, PayPal is best known for its founding team, the so-called PayPal Mafia. Turn to the management section of its initial filing prospectus and you find this: A lot has been written about what these individuals went on to accomplish. Peter Thiel and Elon Musk are two of the most famous people to have come out of Silicon Valley; Max Levchin is the founder of Affirm, Reid Hoffman of LinkedIn, David Sacks of Yammer (acquired by Microsoft); Roelof Botha is the managing partner of Sequoia Capital’s US and European businesses. Only 191 employees worked at the company’s Palo Alto headquarters at the time of its IPO but among them you also find the future founders of Yelp, YouTube and more. It’s not clear how much value has cumulatively been created by this team, but it’s the closest modern-day Silicon Valley has to Fairchild Semiconductor, founded over 40 years prior. In the mid 2010s it was estimated that 70% of publicly-traded tech companies in the Valley trace their lineage to Fairchild. At its current rate, PayPal may yet match that degree of influence. In which case, it's instructive to track back to the days before and after the initial IPO to see what was going on at PayPal to shape such a team. In a new book, The Founders, author Jimmy Soni does exactly that. Using information gleaned from over 260 interviews with former employees and other observers, he recreates the early days of PayPal to ask what was in the water? What comes out is a messy story of productive friction. It wasn’t at all clear that PayPal would be a success. “Properly understood, PayPal’s story is a four-year odyssey of near-failure followed by near-failure.” The team had to contend with all the usual trials of competition, regulation, cash burn and tension among their ranks. But they also had to manage a dynamic power relationship with a third-party platform which was both the source of their growth and potential arbiter of its demise, and – adding another dimension of friction – the team was forced into a perennial game of cat-and-mouse with many of their own customers, out to defraud them. Early DaysPayPal’s roots lie in two distinct companies, neither of which started out with a vision to do online payments. The first, called Fieldlink before it changed its name to Confinity, was founded by Max Levchin and Peter Thiel in December 1998. Levchin was interested in cryptography and built a business around mobile encryption. It was a great idea but he was too early – mobile at the time centred around PalmPilots and enterprise customers weren’t using them enough to warrant spending money on their security. So he and Thiel changed course, first, to use their security solution to offer a “mobile wallet” to users of handheld devices; then to create the functionality for users to “beam” payments between PalmPilots via the infrared ports embedded in their devices; finally – as a workaround for people who may forget to take their PalmPilots out with them – to allow customers to email money to each other.¹ The second company was X.com, founded by Elon Musk in March 1999. Aged 27, Musk had just banked $21 million on the sale of his first venture, Zip2. The way that money arrived prompted him to question the nature of financial services. It arrived by check, “literally, to my mailbox. I was like, ‘This is insane. What if somebody…? I mean, I guess they’d have trouble cashing it?’ But it still seems a weird way to send money.” Musk invested $12.5 million of his gains into X.com with the vision of creating a new internet bank.² He assembled a team comprising Silicon Valley veterans and financial veterans but the sides didn’t get on and there was ample turnover. In contrast to Confinity, which started hyper-niche and migrated into online payments, X.com started with a grand plan to be “a combination of the Bank of America, Schwab, Vanguard, and Quicken.” But, like Confinity, X.com soon found that emailing money – a feature similarly built as an afterthought – exhibited good product-market fit. “We would show people the hard part—the agglomeration of financial services—and nobody was interested. Then we’d show people the email payments—which was the easy part—and everybody was interested,” Musk said years later. The convergence on email payments pitched the two companies against each other. Flush with cash – Confinity raised $11.0 million at the beginning of 2000 and X.com, $12.9 million – the two launched a land grab to win customers. By giving away money to users both for signing up and for encouraging their friends to sign up, the companies expanded their networks and incentivised person-to-person transmission. Confinity gave away $10 per new customer and $10 for a referral; X.com went in at $20 for a new customer and $10 for a referral. To this day, it is a tactic that PayPal employs. Last year, the company began offering a referral bonus of as much as $10 to existing users for signing up a friend. However, not all incentives achieve the desired outcome, and 4.5 million accounts were illegitimately created over 2021. Back in the early 2000s, those numbers would have been mind-boggling. At the end of March 2000, the two companies in combination had 824,000 total accounts. As well as the giveaways, what really drove growth was the rise of online auctions, in particular eBay. Buyers and sellers found the services offered by Confinity and X.com invaluable in processing their transactions. Not that the payments companies anticipated it, nor were they even aware of it until they started investigating. “We thought we would compete with Western Union,” a former X.com engineer tells Soni, “like if you had to send money to your son at college or to pay the landlord rent or something. It was going to replace big, clunky transactions that you would otherwise have to do at a bank. It turns out people are sending ten or twenty bucks for little Beanie Babies.” (Another milestone in the Long, Slow Short of Western Union.) According to one former Confinity employee, “there would be no PayPal today if [PayPal] didn’t have the eBay platform to form their network.” By April 2000, PayPal services appeared on 20% of all auctions on eBay; by late June, that number was 40%. By now, the founders and investors of Confinity and X.com realised that peer-to-peer payments had all the hallmarks of a winner-takes-all market and that they should join forces as a single company. “True networks are a naturally monopolistic business,” said the man who brokered the deal from the X.com side. Negotiations began at a 92–8 exchange ratio in favour of X.com before shifting towards 55–45 and then finally settling at 50–50 after Levchin threatened to call the deal off following a clash with Musk. The monopolistic tendency of the market is reflected in the competition section of the company’s IPO prospectus. Few of PayPal’s direct online point-to-point payments competitors are still around: Yahoo!'s PayDirect, Citibank's c2it, Western Union's MoneyZap. CheckFree, which the company acknowledges as a potential direct competitor, had a chance to buy PayPal but turned it down. Building a Sustainable BusinessFollowing the merger, the newly combined team still had a key question to crack: how to make money. In their first post-merger quarter, they generated just $2.2 million of revenue against $51.4 million of costs. One X.com executive describes the story so far: “PayPal started off as a product with no use case. Then we had a use case but no business model. Then we had to build a sustainable business.” Musk’s grand vision was to harness the full suite of financial services to capture value. Online payments were a means to get funds into the system, which the company could then monetise via the sale of additional financial products. “Whoever can keep the most money in the system wins,” Musk tells Soni. “Fill the system, and eventually, PayPal will just be where all the money is because why would you bother moving it anywhere else?”³ Years later, Ant Group would pioneer this strategy in China and PayPal itself would refresh it with the launch of its super app in 2021. But in 2000, the strategy failed to gain traction. According to Soni, Musk himself kept millions of his own fortune on the platform, but others didn’t follow. So the company simply started charging users to receive money. It began with a fee of 1.9% on payments received and then started inching that up. By the time the company IPO’d, the fee rate was around 3.1%. “We found that the pricing was completely inelastic,” explained Thiel. “As we increased prices, none of our customers could leave. People said, ‘We refuse to pay,’ and they left, and there is no other place they could get paid online so they came back.” With PayPal now generating revenue, eBay began to pay closer attention. eBay had acquired its own payments company, Billpoint, in May 1999 (like X.com, a Sequoia-backed company) but there were delays integrating Billpoint and it failed to win share. Even after eBay brought Wells Fargo in as a partner, Billpoint struggled. In mid 2000, eBay customers used Billpoint in just 9% of auctions. Meg Whitman, eBay CEO, writes in her memoir: “We tried some strategic marketing efforts to woo more customers to eBay’s payment system, but I could see that our users liked PayPal better. It had a great brand name; not surprisingly, consumers like a name with pal in it a lot more than a word with bill in it. What’s more, we were trying to integrate our acquisitions and expand internationally; our marketing battles with Paypal were becoming distracting and expensive, and we weren’t sufficiently closing the gap. I suspected we were going to need to buy PayPal.” Whitman bought PayPal on the fourth attempt. The price rose from $300 million to $500 million to $800 million to $1.5 billion, with the deal floundering on prior attempts either on valuation or on terms. By the time the deal was finally consummated, in July 2002, the two companies were heavily intertwined: over 60% of PayPal’s payments volumes were linked to online auctions, in particular eBay’s. Today, PayPal isn’t as connected to eBay. It was spun back out as an independent company in 2015 and a few years later, eBay announced it would stop working with PayPal as its back end payments service. At the time of the spin-off, eBay accounted for 29% of PayPal’s net revenues, a contribution which fell to 14% in 2020 and is now headed to zero. But eBay’s influence has simply been replaced by that of other large third-party platforms. Amazon doesn’t currently accept PayPal but Shopify does and as Shopify grows its own payments service, many of the same competitive dynamics PayPal negotiated with eBay come back into frame. So far, most of PayPal’s formative experiences are reminiscent of those of other startups – the pivots, the competition, the struggle to capture value. One feature that differentiates PayPal is its war on fraud. Defeating FraudThroughout its history, PayPal has battled against users that want to defraud it. There are two types: merchant fraud, perpetrated by buyers who would buy an item and then demand a refund; and seller fraud, where phoney sellers would dupe unsuspecting customers into buying goods which would never be sent. As PayPal grew, the surface area for both increased. By September 2000, fraud prevention had become a top strategic priority. As Max Levchin said later, “we either figure out how to beat the fraudsters or the fraudsters will take us under. And the company more or less refocused itself as a research entity towards figuring out innovative technological ways of destroying fraud on the Internet.” Reflecting this, Soni’s book is also a book about fraud. He describes some of the solutions the team devised:

By constantly refining its fraud models, PayPal was able to bring its fraud costs right down. In 2001, its provision for transaction losses amounted to 0.42% of total payment volume, down from 0.87% in 2000. According to Levchin: “So the underlying business model of PayPal is actually that of a security company, a risk management company, that provides an extremely important yet commodity business on top.” It was probably underrated at the time of its IPO, but it was this pursuit of fraud prevention that gave PayPal its early competitive edge. Yet to prevent it, the team had to experience it. “Losing a lot of money to fraud was a necessary byproduct in gathering the data needed to understand the problem and build good predictive models,” one former executive writes on his personal blog. Peter Thiel picks up the theme: “one way to describe fraud is that we have a perverse symbiotic relationship with these Russian mobsters who were the primary culprits. Basically, we were in a race to develop new anti-fraud techniques and they were in a race to develop new ways to steal money. The by-product of it was all our competitors got wiped out because as the Russian mobsters got better and better, they got better and better at destroying all of our competitors.” That’s one way to achieve a monopoly. Soni’s recreation of this entire period is the closest you’ll come to a fly-on-the-wall encounter with the PayPal Mafia during this formative time in business history. You won’t come away with a written recipe of what was in the water, but you’ll form a pretty good picture. My own conclusion is that the distinct period during which the team worked together was helpful – their story had a defined beginning and a defined end, when PayPal was sold to eBay. The relatively small size of the company helped as well. Above all, though, this was a young team – the executives had a median age of 31 at the time of the IPO – and so their exit left them with enough time to explore new ventures with the bonus that they now had the money to fund them. The Founders by Jimmy Soni, Simon & Schuster $30, 496 pages 1 Nokia Ventures led a $4.5 million investment round in Confinity in 1999. The firm “beamed” its funds PalmPilot-to-PalmPilot at an event in Buck’s restaurant. 2 Musk was so desperate for the X.com domain name, he acquired it for cash and 1.5 million shares of his fledgling company, equivalent to a 3.9% stake. 3 It’s interesting how much early fintech pioneers’ visions map onto some of the ideas behind crypto and decentralised finance. We’ve discussed this before in relation to Dee Hock, founder of Visa. Jimmy Soni interviewed Elon Musk in January 2019, so it could be that his recollections have been clouded by the passage of time but, on financial infrastructure, this is what he had to say: “Well, why don’t we just allow people to trade with each other? So if I want to send you stock, why don’t I just send you a share of whatever?’ I don’t need to go through anything. The exchange is unnecessary.” You’re on the free list for Net Interest. For the full experience, become a paying subscriber. |

Older messages

Positioning for Rising Rates

Friday, February 11, 2022

Plus: Sculptor Capital Management, Maker DAO, Credit Suisse

Follow the Money

Friday, February 4, 2022

The Story of Swiss Private Banking

The Power Law

Friday, January 28, 2022

Plus: Robinhood, Credit Rating Agencies, Foreign Travel

Great Quarter, Guys

Friday, January 21, 2022

Plus: CBDCs, Insurtech, Bank Regulation

From Co-ops to DAOs

Friday, January 14, 2022

Plus: Citadel Securities, JP Morgan, BlackRock

You Might Also Like

Longreads + Open Thread

Saturday, March 8, 2025

Personal Essays, Lies, Popes, GPT-4.5, Banks, Buy-and-Hold, Advanced Portfolio Management, Trade, Karp Longreads + Open Thread By Byrne Hobart • 8 Mar 2025 View in browser View in browser Longreads

💸 A $24 billion grocery haul

Friday, March 7, 2025

Walgreens landed in a shopping basket, crypto investors felt pranked by the president, and a burger made of skin | Finimize Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March 8th in 3:11 minutes.

The financial toll of a divorce can be devastating

Friday, March 7, 2025

Here are some options to get back on track ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Too Big To Fail?

Friday, March 7, 2025

Revisiting Millennium and Multi-Manager Hedge Funds ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

The tell-tale signs the crash of a lifetime is near

Friday, March 7, 2025

Message from Harry Dent ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

👀 DeepSeek 2.0

Thursday, March 6, 2025

Alibaba's AI competitor, Europe's rate cut, and loads of instant noodles | Finimize TOGETHER WITH Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March 7th in 3:07 minutes. Investors rewarded

Crypto Politics: Strategy or Play? - Issue #515

Thursday, March 6, 2025

FTW Crypto: Trump's crypto plan fuels market surges—is it real policy or just strategy? Decentralization may be the only way forward. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

What can 40 years of data on vacancy advertising costs tell us about labour market equilibrium?

Thursday, March 6, 2025

Michal Stelmach, James Kensett and Philip Schnattinger Economists frequently use the vacancies to unemployment (V/U) ratio to measure labour market tightness. Analysis of the labour market during the

🇺🇸 Make America rich again

Wednesday, March 5, 2025

The US president stood by tariffs, China revealed ambitious plans, and the startup fighting fast fashion's ugly side | Finimize TOGETHER WITH Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March

Are you prepared for Social Security’s uncertain future?

Wednesday, March 5, 2025

Investing in gold with AHG could help stabilize your retirement ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏