|

I’m Isaac Saul, and this is Tangle: an independent, ad-free, subscriber-supported politics newsletter that summarizes the best arguments from across the political spectrum on the news of the day — then “my take.” First time reading? Sign up here. Would you rather listen? You can find our podcast here.

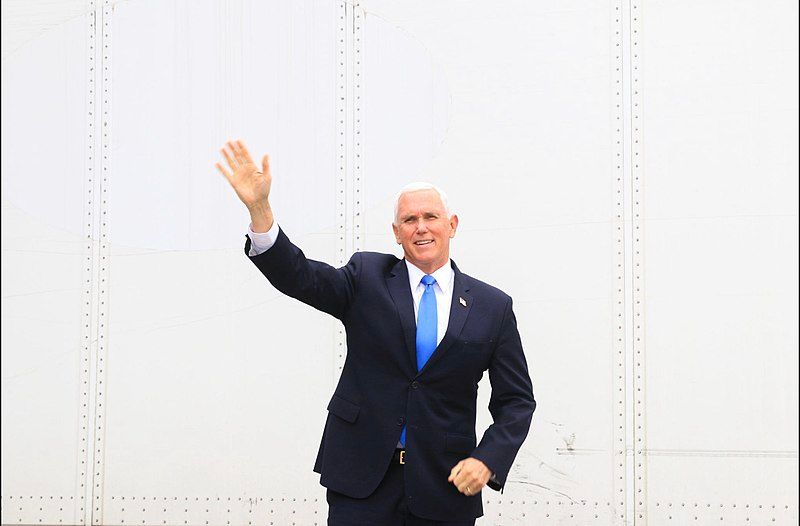

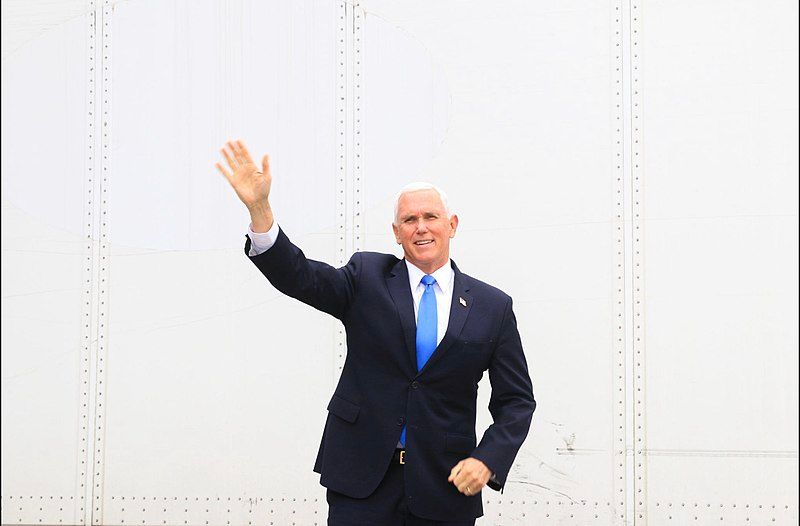

Today's read: 13 minutes.We are covering the Electoral Count Act reforms and skipping our reader question. Plus, a preview of tomorrow and a story on the Cherokee Nation.  Vice President Mike Pence was at the center of a question in 2021 that Congress is now trying to address. Photo: Tom Caprara

Friday edition.Tomorrow, we're going to be exploring a question I get a lot in Tangle: How much does public opinion matter? One of the cynical ideas I encounter a lot is that public opinion doesn't make legislation — rich donors and their money do. Tomorrow, we'll be exploring just how much of an impact public opinion has on legislation, and the ways it does and doesn't change what happens. Reminder: Anyone can read Tangle's Monday-Thursday editions for free, but if you want Friday editions, you have to subscribe.

Quick hits.- New York attorney general Letitia James sued former President Donald Trump and his three eldest children for allegedly misrepresenting their property values (The lawsuit). Separately, the Justice Department won its appeal to retain control of the classified material seized at Mar-a-Lago. (The appeal)

- The Federal Reserve approved another 0.75% interest rate increase, raising the benchmark rate to the highest levels since 2008. (The hike)

- Russian President Vladimir Putin partially mobilized his army reserves for the first time since 1941. The move is considered an escalation in the war, and some 1,200 people were arrested in protests against the mobilization. (The move)

- Russia and Ukraine carried out an unexpected prisoner swap on Wednesday that included almost 300 people, freeing two Americans and eight other foreigners from Russia. (The swap)

- Virginia Thomas, the wife of Supreme Court justice Clarence Thomas, agreed to a voluntary interview with the January 6 House committee. (The interview)

Our 'Quick Hits' section is created in partnership with Ground News, a website and app that rates the bias of news coverage and news outlets.

Today's topic.Electoral Count Act reform. Yesterday, the House passed a bill (The Presidential Election Reform Act) to reform the 1887 Electoral Count Act, which defines the way Congress counts and ratifies presidential elector votes. The bill, co-sponsored by Reps. Liz Cheney and Zoe Lofgren, passed by a 229-203 vote, with nine Republicans and all 220 Democrats supporting it. All nine Republicans who supported the bill will be retiring or have lost their primaries and will not be in Congress next year. The legislation now goes to the Senate, where a separate reform bill (The Electoral Count Reform and Presidential Transition Act) has already been proposed and garnered the necessary 10 Republican votes to pass. But there are some key differences between the two bills. The history: Before the Electoral Count Act was passed in 1887, the guidelines for how to conduct presidential elections were rather straightforward. Every state ran its own election and each state was worth a certain number of electoral college votes. When votes were counted in the state, that state certified a winner, and then the electoral votes were sent to Congress by each state to be counted. The Constitution says, "The president of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates, and the votes shall then be counted." In 1876, though, this process blew up during a contested election when states sent in conflicting slates of electors. Two contested elections and a decade later, Congress tried to prevent this from happening again by drafting the Electoral Count Act, which specifies when and where Congress shall convene to count electoral votes (at 1 p.m. EST on January 6). This bill also drew up clear guidelines on how members of Congress may object to the count. However, election experts have long complained that the bill is convoluted and unworkable, and it's been contested since its inception. One major problem is the legislation allows members of Congress to object to the results from individual states, despite the Constitution explicitly saying members' responsibility is only to count the electoral votes. It does not clearly lay out how to resolve a contested election, and does not clearly define the role of the vice president in such a conflict. In 2021, former President Trump pressured then-Vice President Mike Pence to reject some electors, which Pence refused to do. This was the same day rioters ransacked the Capitol as Congress was convening to count the votes. Since then, members have been discussing a fix to clear away any ambiguity about the process and to make it clear an election can't simply be halted or overturned by any single person. Both bills attempt to clarify that Congress's role in ratifying states' electoral college votes is procedural, and that the vice president's role is only to publicly count the votes. Both bills remove language that would allow state legislatures to override the popular vote in the event of a "failed election," a term not defined in law. Both bills set rules to ensure state legislators can't alter election procedures after Election Day to benefit one candidate. Both bills also raise the threshold from Congress needed to object to state electors. Currently, just one member of the Senate and House are needed to object to a state's electors. The Senate bill raises the threshold to one-fifth of each chamber; the House bill raises it to one-third of each chamber. Other major differences include who can sue over election results in federal courts. The Senate bill allows existing state and federal laws to resolve most election disputes, introduces a fast-tracked judicial review of claims made by candidates, and creates a three-judge panel that can directly and quickly appeal to the Supreme Court. The House bill also includes avenues for a three-judge panel and direct appeal to the Supreme Court, but makes it clear that candidates can sue in federal court if a governor fails to transmit lawful election results to Congress. The House bill also lengthens the period of time allowed to resolve legal disputes from six to nine days, and avoids language in the Senate version that characterizes a governor's certification of a state's results as "conclusive." Finally, the House bill codifies that Congress can only object to electoral votes on very specific grounds, limited to “the explicit constitutional requirements for candidate and elector eligibility and the 12th Amendment’s explicit requirements for elector balloting.” It also provides grounds for objecting to a candidate’s eligibility under Section 3 of the 14th amendment, which bars anyone who has engaged in an insurrection from holding any public office. Below, we're going to take a look at some reactions to the House and Senate bills as well as some overall arguments about reforming the Electoral Count Act. We previously covered this issue in January.

What the right is saying.- Many on the right support reforming the Electoral Count Act.

- Some argue that the Senate bill is a superior version, while others prefer the House version.

- Others say the reforms are a partisan attempt to give more election power to the federal government.

In The Washington Examiner, Dennis Ross and Erik Paulsen wrote favorably about the Senate bill. "The recently proposed Electoral College Reform Act provides several solutions to the vaguest provisions within the ECA that have been used to cast doubt on the certification process," Ross said. "Notably, it would establish clear procedures that clarify the state and federal roles in selecting the president and vice president. For example, it establishes that the governor of each state is the person to certify the state’s slate of electors rather than Congress and clarifies that states must appoint electors in accordance with the laws they had before Election Day. The legislation would also raise the threshold to lodge an objection to electors and narrows the grounds for filing objections. "These particular provisions are rooted in conservative governance. As conservatives themselves have stated, the current ECA reform hardens the powers of individual state authority with the Electoral College at a time when liberals want to repeal the Electoral College," they wrote. "Furthermore, removing powers (or the illusion of power through ambiguity) from federal officials like the vice president at the same time only further empowers the states. Such provisions inherently decentralize government power and ensure a peaceful transition of power by preventing mischievous actors in Washington from sowing doubts about the outcomes of an election." The Wall Street Journal editorial board wrote in support of the newly introduced House version. "Where the House bill might be an improvement is in making it harder for partisans in Congress who want to get C-Span-famous to lodge phony Electoral College objections," the board said. "Only a specified set of complaints would be heard, such as if a state sends too many electors; if electors vote on the wrong day or are ineligible; or if the presidential or vice presidential candidate is ineligible. No whining on the House floor that somebody had a funny feeling about the vote totals in west southeastern Pennsylvania. "The best approach remains for lawmakers to get out of this objection business and leave such disputes to the courts," they added. "The House bill retains a purported authority to reject Electoral College votes if Congress decides that the incoming President is constitutionally ineligible. But isn’t 14 days before Inauguration Day a little late for that, folks? Imagine if President Trump wins a landslide in 2024 and then Democrats move to invalidate his electors, saying that Mr. Trump led an “insurrection” as defined under the 14th Amendment. Perhaps it’s unrealistic to expect lawmakers to give up the power they arrogated in 1887, but the madness of Jan. 6, 2021, should have made a convincing case." However, some are skeptical of the proposals, especially the newly introduced House bill. In The Federalist, Tristan Justice called it a "trojan horse." "Cheney’s 'Presidential Election Reform Act' became the Democrats’ answer to their failed effort to override state election laws in H.R. 1, which Senate Republicans blocked last summer," Justice wrote. "The legislation carries some of the same provisions of the doomed election bill at the top of Democrats’ congressional agenda. Just nine Republicans supported the bill, all but one of whom supported President Donald Trump’s second impeachment and are either retiring or have lost their primaries. "New York Republican Rep. Claudia Tenney, who co-chairs the Election Integrity Caucus, condemned the bill as 'the latest attempt from House Democrats to stack the democratic process in their favor' and complained that the proposal did not go through the proper legislative process," he said. "The text was only released days before the Wednesday vote and received no bipartisan hearing or markup in committee... In 2017, Democrats objected to more states certifying President Donald Trump’s win than Republicans did four years later for Joe Biden."

What the left is saying.- The left is supportive of both reforms, though they seem to favor the House bill.

- Some criticize the Senate version for not going far enough.

- Most just want to ensure that something is passed to prevent even the possibility of another January 6.

Greg Sargent and Paul Waldman wrote in support of the new House bill. "Under the Senate bill, if a corrupt governor certifies electors in defiance of the popular vote, an aggrieved candidate can take it to court," they said. "A federal judicial panel would weigh in and designate which electors are the legitimate ones, subject to Supreme Court review. Congress would be required to count those legitimate electors. But there, a problem might arise. If the corrupt governor simply ignores the new law and disregards what the court said — and certifies fake electors in defiance of that court ruling — then a GOP-controlled House of Representatives could also ignore the new law and count those fake electors. "The House bill adds an additional safeguard: If a corrupt governor defies that judicial panel review and refuses to certify the electors the panel deemed the legitimate ones, the House measure empowers that panel to designate another state official to certify those legitimate electors. Congress would then be required to count those electors. This would effectively take the weapon out of the hands of the corrupt governor entirely," they wrote. "That “rogue” scenario could happen if Republicans win governorships in swing states other than Pennsylvania. For instance, in Arizona, GOP nominee Kari Lake has made questioning the 2020 election central to her campaign. In Michigan, nominee Tudor Dixon has spread Trump’s 2020 lies." In New York Magazine, Ed Kilgore wrote that Democrats should take the Senate bill. "In a very short period of time, the window for a congressional fix of the Electoral Count Act of 1887 — the dusty, convoluted statute that made the events of January 6 possible — will probably close," Kilgore said. "So for the foreseeable future, and most definitely for the period before MAGA forces have the chance to consider another coup, there is one and only one chance to make the counting of presidential electors the uneventful chore it was always intended to be... Yes, there are some minor differences between the House and Senate bills. Most notably, the Senate bill would raise the threshold of one-fifth of the members of both chambers to trigger a debate and vote on challenges to certified electoral votes, while the House bill would raise that threshold to one-third of the members. More to the point, the threshold will likely remain at one member of each chamber if a fix is not enacted by the end of this Congress. "Yes, it’s unfair the Senate gets to call the shots on issues like this, but they’re the ones with the arcane rules and the still-rampant filibuster, which aren’t going to be fixed in this Congress," he said. "So if House reformers want to reform the ECA, they really absolutely have to swallow their pride and take the Senate bill with whatever minor changes can be negotiated quickly. Such a “surrender” would obviously pale next to the concessions the House has had to make to the Senate on virtually every other piece of legislation this year – most notably the massive package that ended life as the Inflation Reduction Act after nearly being throttled altogether." In Democracy Docket, Democratic lawyer Marc Elias wrote about his concerns over the Senate bill. "At the heart of my concern with this bill is the requirement that at least six days before the Electoral College meets, each governor must submit a 'certificate of ascertainment' identifying their state’s presidential electors. According to the new bill, that document is 'conclusive with respect to the determination of electors appointed by the state.' Conclusive is a very strong word," Elias said. "Typically, in legal construction, a fact or piece of evidence is conclusive when it is settled and cannot be contradicted by other facts or evidence. For decades, the U.S. Supreme Court has reasoned that if something is conclusive, it is 'incapable of being overcome by proof of the most positive character.' "Under such an interpretation, the declaration by a governor that a Republican presidential candidate received more lawful votes than the Democratic presidential candidate could not be challenged even if there was strong evidence to the contrary," he wrote. "If elected this November, a future Gov. Kari Lake (R-Ariz.) or Gov. Doug Mastriano (R-Pa.) could certify the 'Big Lie' presidential candidate as the winner even if the best evidence showed that he or she had lost the presidential election. That 'conclusive' determination would be the end of the analysis. Proponents of the [Senate] bill will point to another part of the law to support the idea that the governor’s conclusive determination is, well, not conclusive at all. Yet, that provision is a bit of a muddle."

My take.Reminder: "My take" is a section where I give myself space to share my own personal opinion. It is meant to be one perspective amid many others. If you have feedback, criticism, or compliments, you can reply to this email and write in. If you're a paying subscriber, you can also leave a comment. - I'm supportive of both reforms, and hopeful one will pass.

- Oddly enough, it seems clear to me the text of the House bill is superior.

- Unfortunately, the process was inferior.

Something interesting happened as I was researching this piece and going through all these arguments. I noticed that — on both sides of the aisle — there was significant division, but also agreement. Bastions of right-wing thinking like The Wall Street Journal editorial board spoke clearly in favor of the House version of this reform, as did hardline liberals like The Washington Post's Paul Waldman and Greg Sargent. At the same time, The Cato Institute and Ed Kilgore, two ideological sources you'd typically expect to be polar opposites, agreed on the need for such reform now. Usually, when there is a big mix of ideas and agreement and division like this across the political tribes, I find myself in conflict, too. But oddly enough, "my take" on this is actually more direct than usual: I think the House bill is clearly superior. This is for a few reasons. Before I explain them, though, let me say unambiguously that I'd be glad to see either bill become law. The Senate bill is a product of good bipartisan work, amending and negotiation. It does the same work the House bill does to remove any doubt about when and where an election can be challenged or upheld. Before January 6, 2021, America had a perfect record on peaceful transfers of power, and we should do everything we can to make sure the next several centuries bring that streak back. Unfortunately, the drawn out and arduous process around the Senate bill seems to have reproduced a couple of the same problems found in the original 1887 act, though to a less significant degree. For starters, the Senate bill still has muddy language that doesn't properly distinguish between objections to electors and objections to electoral votes. It also leaves language around "regularly given" votes in place, the same language that has wreaked havoc on elections for the last 20 years. The House bill makes it clear precisely what kinds of objections would be heard, which — as The Wall Street Journal editorial board rightly says — will undoubtedly reduce the number of charlatan objections from either side. Cheney and Lofgren's explanation of the bill put it in very clear terms: "If members of Congress have any right to object to electoral slates, the grounds for such objections should be narrow. Congress doesn’t sit as a court of last resort, capable of overruling state and federal judges to alter the electoral outcome. If any objections are allowed during the joint session, grounds should be limited to the explicit constitutional requirements for candidate and elector eligibility and the 12th Amendment’s explicit requirements for elector balloting." I also appreciate the higher threshold for objections from the House and Senate. One member in each body being able to halt an election was always an absurd notion, but one-fifth is still not high enough. The threshold for impeaching a president is two-thirds majority. The threshold for objecting to a state-certified election should be, at least, one-third of both chambers. Here, the House bill is again superior. Both bills lean on the courts to resolve disputes, but the House bill allows more time for a resolution and leans into existing mechanisms to challenge an election result. And perhaps most importantly, the House bill does not include language that a governor's certification is "conclusive." The Senate bill includes this language, then tries to clarify that a governor's certification isn't actually conclusive, leaving a reader with the uneasy feeling there is a crack ready to be exposed. States should have full control over their elections, but no single person should be granted "conclusive" certification of such an election. The House bill better clarifies the powerful but finite role a governor plays in certifying votes — and makes it clear that if a corrupt governor ignores a court’s order on certifying legitimate elections, the court can direct another state official to do the governor’s duty instead. In sum, the House bill has more safeguards, clearer language, and a higher threshold for upending an election. The House bill’s downside is the process and the people behind it. Cheney is a poison pill for Republicans, so her bill is going to draw opposition no matter what is in it — especially in the context of it being drafted, driven and supported by so many outspoken Trump opponents. It was also passed hurriedly, with little oversight or negotiation, unlike the Senate bill. The perfect scenario would be the text of the House bill combined with the process of the Senate bill. With any luck, the Senate bill will be further amended to move toward the House bill and then pass, with a wide range of bipartisan support in Congress and among the pundits. Either way, it's clear Congress needs to do something, and the bare minimum of simply clarifying its role as mostly ceremonial is pressing.

Your questions, answered.Today's main topic is a bit convoluted and confusing, so we are giving it some extra space to breathe and skipping our reader question. Want to ask a question? You can reply to this email and write in (it goes straight to my inbox) or fill out this form.

Under the radar. The Cherokee Nation is asking for a seat in Congress. A new campaign is being launched to prod Congress to honor a 19th century treaty that has been ignored. In 1835, then-President Andrew Jackson signed the Treaty of New Echota, which was ratified by Congress and promised a nonvoting House delegate to the Cherokee Nation. The same treaty forced the Cherokee Nation to go to Oklahoma, moving there from Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia. No such delegate has ever been seated, though the Cherokee Nation has named Kim Teehee as its delegate. If seated, she'd be able to give House floor speeches and vote in committee, but not on final legislation. Axios has the story. Have a story you think is slipping under the radar? Submit one here.

Numbers.- 16.17%. The average annual percentage interest rate on a credit card in May.

- 18%. The average annual percentage interest rate on a credit card now.

- $14. The rough increase in interest the average household will pay each month on their credit card.

- $250. The increase in the monthly cost of a typical mortgage on a median-priced home, because of increased interest rates.

- 729. The number of attempted book bans logged by the American Library Association in 2021.

- 156. The number of attempted book bans logged by the American Library Association in 2020.

Have a nice day.Cancer death rates in the U.S. are continuing to fall thanks to advancements in treatment, diagnostic tools and prevention strategies. There are now more than 18 million cancer survivors in the U.S., up from 3 million in 1971. Death rates from cancer have been falling for over two decades, but the decline has become even sharper in the last few years. Between 1991 and 2016, the cancer death rate fell 27%, according to the Cancer Society. Between 1991 and 2019, the overall cancer death rate reduction translates to 3.5 million lives saved. CNN has the story.

❤️ Enjoy this newsletter? 💵 Drop some love in our tip jar. 📫 Forward this to a friend and let them know where they can subscribe (hint: it's here). 📣 Share Tangle on Twitter here, Facebook here, or LinkedIn here. 🎧 Rather listen? Check out our podcast here. 🛍 Love clothes, stickers and mugs? Go to our merch store!

|