Not Boring by Packy McCormick - How Do I Teach These Kids?!

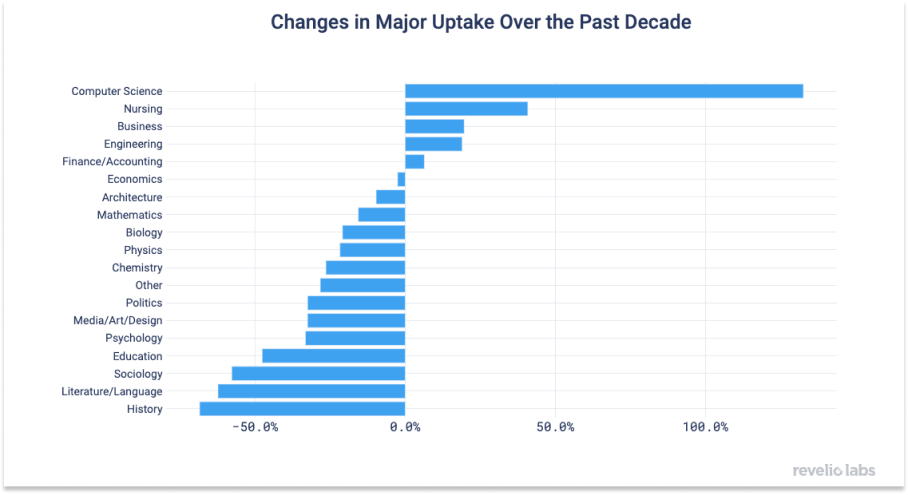

Welcome to the 873 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday — I need to take breaks more often! If you haven’t subscribed, join 155,416 smart, curious folks by subscribing here: 🎧 For the audio version, listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts Hi friends 👋, Happy Monday! Big week here at Not Boring HQ: Friday was Puja and my 5th anniversary (Happy Anniversary Puj!), tomorrow is Dev’s 2nd birthday, and Thursday is Maya’s 2-month birthday. Last year, when Dev turned 1, I wrote Dad Life, a piece about working and raising a kid at the same time. I wasn’t planning on writing a similar piece for his birthday this year, but I’ve been thinking a lot about a related question and the timing worked perfectly. The question is: how the hell are you supposed to educate a kid today? Dev and Maya get a blank educational slate to start with. Puja and I are responsible for figuring out how to give them the best education possible, one that helps them love learning, have fun, and get prepared for life beyond school. I don’t think the answer is as simple as “Get them into the best schools possible.” I think it’s a lot more complicated than that, and will only get more complicated as things move faster. This isn’t meant to be a complete survey and analysis of the modern educational system, it’s more of an exploration of how I’m thinking about it personally in the very specific context of Dev and Maya’s education. What’s the best way to prepare my two kids? And I don’t have the answers – there’s probably no “right” answer. Instead, this is meant to start a conversation, and selfishly, to give me some more direction as I think through it. I’d love to hear your thoughts, jump in here:  Let’s get to it. How Do I Teach These Kids?!Now that we have kids, my most important job is raising them. I want them to be happy and kind and smart and creative and hard-working and a little devilish. I remember walking around holding Dev when he was really little and telling him those things, listing the qualities I wanted to instill in him as if he could absorb the words and make them so. In reality, it’s a lot harder than that. A timely example. Last night, after we had our family over to celebrate his birthday, I gave him a bath, put him in his pajamas, and started reading him a book, Goodnight, Goodnight Construction Site to be exact. As we were finishing – “Great work today! Now…shh…goodnight!” – my mind was already on getting back to work and finishing this piece. I was tired, and starting back up after a long day was already daunting enough. When he asked, “Can we read one more book please?” I started to shake my head no, tell him it was time to go to sleep, that dad had to work… and then I remembered what I was about to go work on: an essay about educating him and his sister. The hypocrisy was too thick. We read another book. There are a million little trade-offs like that, though rarely quite so on the nose. Historically, the way to deal with a big lump of those trade-offs is, eventually, to try to put your kids in the best schools possible and make sure that they’re doing their homework and getting good grades and doing all of the extracurriculars, which serve double duty as resume fillers and extra childcare. But thanks to the pandemic and our jobs, Puja and I have been lucky enough to be home most of the time, getting to spend time with Dev and Maya, getting to watch them get smarter every day, like little human large language models with big emotions. At the same time, the real large language models have been getting stronger by the day, surprisingly upending creative work first, which has made me reflect on what the world will look like when they’re older, and how to prepare them for that world. What will people need to know in a world in which the Enchanted Notebook exists? While we’ll still put them in school – Dev started a couple weeks ago, for a few hours three days a week – it’s become clear that if we want them to grow up to be uniquely them to the fullest of their potential, and stay ahead of seemingly daily advances, we need to do a lot more than that. The question is, what? And I guess another one is, how? How do we teach these kids?! There are these charts that pop up every once in a while that show how much graduates of certain majors make or which majors are becoming more popular. One that has recently caught peoples’ attention is this chart that shows that computer science degrees are on the rise, and humanities degrees are on an equal and opposite decline. This chart has caused either celebration (“Good! People are studying things that will help them get jobs.”) or anguish (“Oh no! The death of humanities will lead to a duller, less ethical and moral society.”). I don’t have a strong view. What struck me when I looked at the chart, and the related hot takes on Twitter, was just how hard it must be for educational institutions at all levels to keep up with the increasing rate of change in the world. It’s an oft-cited fact that the modern education system was created during the Industrial Revolution to prepare children to grow up to work in factories. “Factory schools,” as they were called, sprang up in Prussia in the 19th Century and quickly spread throughout the industrialized world, to teach kids to be “punctual, docile, and sober.” Moving from the family farm to the corporate factory required a different set of skills and behaviors, and schools stepped in to teach them. That model worked well, and persisted for two centuries, in part, I would guess, because the types of jobs that people were going to get after school, and the skills they would need for those jobs, stayed relatively static. And a literate, numerate population trained to follow orders generalized well. The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit worked in an office instead of a factory, and wore nicer clothes, but was still expected to be punctual, docile, and sober. While some of the details have changed, the system works largely the same way today, even among the top students at the best schools. When I asked people for their favorite essays, William Deresiewicz’s Solitude and Leadership was one of the most frequently-recommended (I marked it up with notes in Readwise Reader here). The essay is the transcript of a talk Deresiewicz, a former Yale English professor and author, gave to the incoming plebe class at West Point in 2009. While at Yale, Deresiewicz spent some time on the admissions committee, where he experienced this:

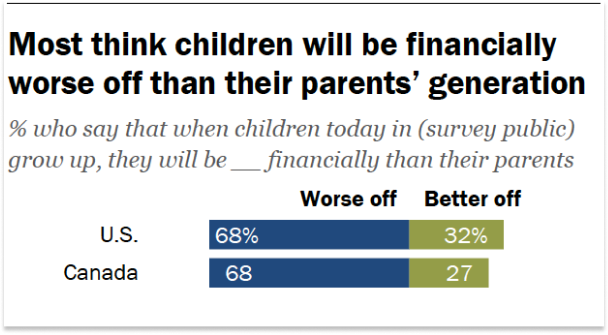

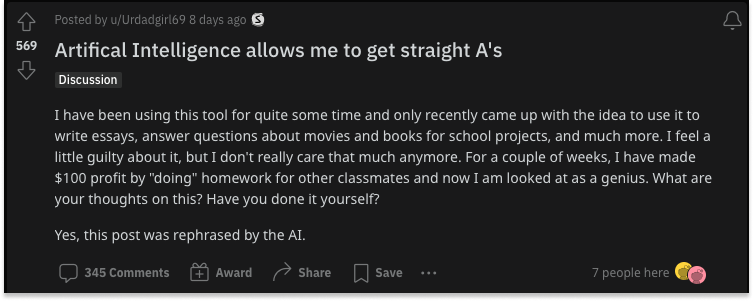

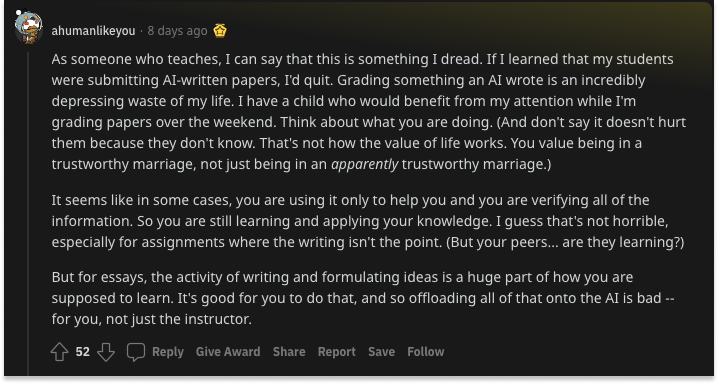

I definitely want my kids to be able to get into schools like Yale, if they want and if that still matters then, but I definitely don’t want them to be excellent sheep. Excellent sheep seldom make history. While I don’t have answers to the very difficult question of how to educate millions of kids, kids of all backgrounds and levels of income and aptitude and parental support, and I don’t envy those who have to come up with those answers, it’s become pretty clear to me that optimizing just for my own kids, the factory school model, or the more modern excellent sheep model, won’t work. I say that as an excellent sheep myself. I was lucky enough to go to great private schools and to Duke. I was a good student. I did a lot of extracurriculars. I remember one weekend in high school when I had a debate tournament one night, ran in Pennsylvania Cross Country State Championship (and finished All-State) the next morning, and drove back to my high school to perform in the school play that same night. In college, I studied econ, because I wanted to go into finance, and then spent four years in a finance job I didn’t love doing work I didn’t really care about and that I realized I was worse at than a lot of people who were plain smarter and actually loved the work. It took me a decade post-college, and unemployment at the start of a global pandemic, to find the thing that I was uniquely good at: writing a newsletter, of all things. I think that a lot of the things I did, in a roundabout way, contributed to what Not Boring has become. Debate helped me frame an argument, finance helped me use a spreadsheet, running helped me put in countless hours of hard work with almost no benefit to show for it for over a year. In retrospect, I wouldn’t change a thing about my education because I’m really happy with where it’s all led. Serendipity is part of the process, and my parents raised us to be able to follow it. They led by example – both leaving good, stable jobs to start their own things – and as a result, my sister, brother, and I all started our own things. But I also want our kids to be better off than us, something that only a depressing 32% of Americans expect to be true for their children: Finances aside, Dev and Maya will set their own definitions of “better off” and their own goals in life, but when I think about how I want to guide them, the words “Philosopher King and Queen” come to mind. The idea, put forth by Plato in The Republic, is that the ideal polis, the kallipolis, or beautiful city, should be ruled by philosophers who love knowledge, who seek truth and ideals instead of power. It’s an idea as beautiful as it is impractical. Plato is essentially calling for benevolent dictatorship and assuming that there exist people who absolute power wouldn’t corrupt absolutely. If some people throughout history may have fit the bill, they’re too few and far between for benevolent dictatorship to be a realistic form of governance, so we’re left with democracy, “the worst form of government – except for all the others that have been tried.” I still think it’s a good north star for raising a kid, particularly when those kids are going to grow up into a world in which they’ll have more power at their fingertips than our generation can even imagine. Dev and Maya won’t be Philosopher King and Queen of the United States, but they’ll be Philosopher King and Queen of their own little worlds. They and their fellow Gen Alphas will command personalized AI and govern decentralized organizations and access overwhelming amounts of information and bring ideas to life with Enchanted Notebooks and shape biology itself, and I think that it’s going to be important for them to grow up with a philosopher’s love of truth and wisdom and a benevolent monarch’s sense of fairness and goodness. And above all else, I want them to have a critical curiosity and pragmatic optimism, a willingness to explore new things openly and excitedly but with a more incisive and critical eye than I have. And I think that the Factory School / Excellent Sheep model is increasingly incapable of making that happen. For one thing, I have no idea what skills are going to be in-demand in twenty years, when Dev would graduate college, or twenty-two, when Maya would. There’s no factory job waiting on the other side, the corporate ladder gets more slippery every year, and the well-worn banking/consulting/law/medicine path seems less certain. Ok, well duh consulting and banking aren’t the sure-things they once were. Everyone who makes real money today knows how to code. That’s why college students are abandoning the humanities in favor of computer science. Teach a kid to code, feed her for a lifetime. We sent Dev to a school that will start to teach him the very basics of coding next year, when he’s three. That’s the obviously right call, right? Not so fast.  Ok, so then I’ll teach my kids ~*prompt engineering*~. If AI is the future, then we should teach our kids to get really good at getting AI to do exactly what they want, like this young genius, Urdagirl69. This Reddit post went viral last week. An enterprising young student figured out that she could use GPT-3 to help write her essays (she used it as a starting point, and then made the essays her own). Writing good essays became so easy, in fact, that she was able to write her classmates’ essays, too, for a $100 profit. One teacher replied that, “If I learned that my students were submitting AI-written papers, I’d quit. Grading something an AI wrote is an incredibly depressing waste of my life.” While I sympathize with the teacher – spending your life grading papers written by AI does seem incredibly depressing – I want to teach my kids to be more like Urdagirl69. By that, I don’t specifically mean that I want to teach them how to use GPT-3 to write essays and build a modern paper-farm lemonade stand, but that I want to teach them to have the curiosity, agency, and initiative to use whatever tools they have at their disposal to do the best work possible. Urdagirl69 seems excellent, but not sheep-like. GPT-3 will be ancient, ancient technology by the time Dev and Maya are assigned their first essay, but the erudite impishness required to seek out and deploy whatever the current most advanced technology is in order to do their work, even if it’s kind of against the rules, is something I want to instill in them. That doesn’t mean that there shouldn’t be rules, or that we should teach them to break the rules for rule-breaking’s sake. Setting boundaries seems important, if only so they can find creative ways around them. On a recent Lunar Society podcast episode, Dwarkesh Patel asked Tyler Cowen if we should just let high schoolers go wild and educate themselves without structure, and Cowen’s response seems instructive for designing educational systems in a world in which kids can write essays with AI: “I think they need some structure, but you have to let them rebel against it, and do their own thing also.” To read the rest of the piece, including thoughts from Patrick Collison, Erik Hoel, and Emad Mostaque and the 10 things I’m going to focus on:Thanks to Dan and Puja for reading and editing! That’s all for today. See you back here Friday for your Weekly Dose of Optimism. Have a great week. Thanks for reading, Packy If you liked this post from Not Boring by Packy McCormick, why not share it? |

Older messages

Weekly Dose of Optimism #14

Friday, September 30, 2022

Progress and Optimism, Marathon World Records, Mammal Comebacks, DART, a Nuclear Enchanted Notebook, and The World's Fair Co.

Tegus: The Outsiders

Thursday, September 29, 2022

Meet the under-the-radar $3 billion company modernizing investment research

The Enchanted Notebook

Monday, September 26, 2022

Or, How to write the future into existence

Weekly Dose of Optimism #13

Friday, September 23, 2022

Adnan, Incarcerated Coders, NEPA Changes, The Lithium Beat, Breakthrough Prizes, Extinct Influenza

Indistinguishable from Magic

Monday, September 19, 2022

Magical Technology: iPod, Spotify, Figma, AI Art, Arc, web3, and beyond

You Might Also Like

Meet Your NEW AI Co-Pilot: Ember

Friday, February 28, 2025

It's pre-trained on tons of ClickBank products... View in browser ClickBank Have you heard of Ember, ClickBank's premier AI copilot? Simple, effective, and built to fuel your business, Ember is

Definitely maybe

Friday, February 28, 2025

Crystallizing the value of Caesars Digital comes with complications ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

+34% more leads (study)

Friday, February 28, 2025

I love that you're part of my network. Let's make 2025 epic!! I appreciate you :) Today's hack +34% more leads (study) Diego Chacon decided to test what specific format of the same offer (

🔍 Why Brands Need To Launch A Social Show

Friday, February 28, 2025

February 27, 2025 | Read Online All Case Studies 🔍 Learn About Sponsorships Social is becoming the new TV. From our consumption habits to the content types - every day we progress to a landscape where

High-traffic sites less than a year old

Friday, February 28, 2025

These numbers are wild

Help me help you!

Thursday, February 27, 2025

Your opinion means everything hey-Jul-17-2024-03-58-50-7396-PM Can you believe Masters in Marketing is already 8 months old? Aw, so cute! And, like any anxious new parents, we want to know how we'

Discover a preview of the content keeping Digiday+ members ahead

Thursday, February 27, 2025

Digiday+ members have more ways than ever to stay ahead of the news and trends transforming media and marketing. Explore premium content from our editors below, including weekly briefings, research and

See you in Boston?

Thursday, February 27, 2025

...back in person for the first time since 2019! Exploding Topics Logo Presented by: Semrush Logo You follow Exploding Topics because you want to get an edge on your competition. Now take that

Why I'm doubling down on my community in 2025... (free bonus)

Thursday, February 27, 2025

Hi there 2025 is chugging along (it's almost March!) – and there's a ton going on right now. But there's something that hasn't changed. Your agency still needs a constant stream of new

Programmer Weekly - Issue 243

Thursday, February 27, 2025

February 27, 2025 | Read Online Programmer Weekly (Issue 243 February 27 2025) Welcome to issue 243 of Programmer Weekly. Let's get straight to the links this week. Streamline IT management with