Astral Codex Ten - Book Review: Malleus Maleficarum

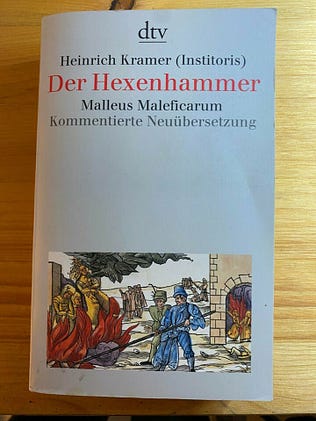

I. To The Republic, For Witches StandDid you know you can just buy the Malleus Maleficarum? You can go into a bookstore and say “I would like the legendary manual of witch-hunters everywhere, the one that’s a plot device in dozens of tired fantasy novels”. They will sell it to you and you can read it. I recommend the Montague Summers translation. Not because it’s good (it isn’t), but because it’s by an slightly crazy 1920s Catholic priest every bit as paranoid as his subject matter. He argues in his Translator’s Introduction that witches are real, and that a return to the wisdom of the Malleus is our only hope of standing against them:

And is this “world-wide plot against civilization” in the room with us right now? In the most 1920s argument ever, Summers concludes that this conspiracy against civilization has survived to the modern day and rebranded as Bolshevism. You can just buy the Malleus Maleficarum. So, why haven’t you? Might the witches’ spiritual successors be desperate to delegitimize the only thing they’re truly afraid of - the vibrant, time-tested witch hunting expertise of the Catholic Church? Summers writes:

Big if true. I myself read the Malleus in search of a different type of wisdom. We think of witch hunts as a byword for irrationality, joking about strategies like “if she floats, she’s a witch; if she drowns, we’ll exonerate the corpse.” But this sort of snide superiority to the past has led us wrong before. We used to make fun of phlogiston, of “dormitive potencies”, of geocentric theory. All these are indeed false, but more sober historians have explained why each made sense at the time, replacing our caricatures of absurd irrationality with a picture of smart people genuinely trying their best in epistemically treacherous situations. Were the witch-hunters as bad as everyone says? Or are they in line for a similar exoneration? The Malleus is traditionally attributed to 15th century theologians/witch-hunters Henry Kramer and James Spengler, but most modern scholars think Kramer wrote it alone, then added the more famous Spengler as a co-author for a sales boost. The book has three parts. Part 1 is basically Summa Theologica, except all the questions are about witches. Part 2 is basically the DSM 5, except every condition is witchcraft. Part 3 is a manual for judges presiding over witch trials. We’ll go over each, then return to this question: why did a whole civilization spend three centuries killing thousands of people over a threat that didn’t exist? II: Thou Shalt Have Witches In HeavenAlmost half the Malleus is devoted to purely philosophical questions surrounding witchcraft. Paramount among these: why would a perfectly just God allow witches to exist? The answer probably has something to with the Devil. And you can probably get part of the way by saying that God has a principled commitment to let the Devil meddle in human affairs until the End of Days. But then you get another issue: the Devil was once the brightest of angels. He’s really really powerful. Completely unrestrained, he can probably sink continents and stuff. So why does he futz around helping elderly women kill their neighbors’ cattle? Put a different way, there’s a very narrow band between “God restrains the Devil so much that witchcraft can’t exist” and “God restrains the Devil so little that witches have already taken over the world”. Prima facie, we wouldn’t expect the amount God restrains the Devil to fall into this little band. But in order to defend the existence of witchcraft, Kramer has to argue that it does. His arguments ring hollow to modern ears, and honestly neither God nor the Devil comes out looking very good. God isn’t trying to maximize a 21st century utilitarian view of the Good, He’s trying to maximize His own glory. Allowing some evil helps with this, because then He can justly punish it (and being just is glorious) or mercifully forgive it (and being merciful is also glorious). But, if God let the Devil kill everyone in the world, then there would be no one left to praise God’s glory, plus people might falsely think God couldn’t have stopped the Devil if he’d wanted to. So the glory-maximizing option is to give the Devil some power, but not too much. Meanwhile, the Devil isn’t trying to maximize 21st century utilitarian evil. He’s trying to turn souls away from God. So although he could curse people directly, what he actually wants is for humans to sell their soul to him in exchange for curse powers. So whenever possible he prefers to act through witches. The rest of this part is just corollaries of these basic points. But there sure are a lot of corollaries, like: Question III: Whether Children Can Be Generated By Incubi And Succubi So, we all know that sometimes demons who look like hot men come and have sex with women in the middle of the night. But can these demons make a woman pregnant? It would seem that the answer should be no, because the Bible says God created Man in His own image, which suggests the conception of new humans is pretty holy, which makes it sound kind of blasphemous to suggest demons could do it. On the contrary side, we know that demons can have kids with humans. The Bible says so: Genesis 6 talks about nephilim, children of “the sons of God” by “the daughters of men”. And St. Augustine seems to think all those stories about Greek gods impregnating women were incubus demons. So “it is just as Catholic a view to hold that men may at times be begotten by means of incubi and succubi, as it is contrary to the words of the Saints and even to the tradition of Holy Scripture to maintain the opposite opinion.” Since the incubi cannot produce semen themselves, probably they steal it from some other human, then bring it to the womb of the person they are having sex with. Question VI: Concerning Witches Who Copulate With Devils - Why Is It That Women Are Chiefly Addicted To Evil Superstitions? Why are most witches women? Probably because women are awful:

In fact, the word for woman in Latin is femina, which can also have the form feminus, which is literally just fe minus (lesser in faith)! Because women are less faithful, more carnal, and mentally weaker, they are more easily tempted by the Devil, and make up the majority of witches. Question IX: Whether Witches May Work Some Prestidigitory Illusion So That The Male Organ Appears To Be Entirely Removed And Separate From The Body. IE: can witches steal your penis? It would seem that witches can steal your penis. After all, many people claim to have had their penis stolen by witches. The fifteenth-century peasants among whom Kramer went witch-hunting claimed this. And modern people claim it even today. Frank Bures’ The Geography Of Madness is a great book about recent penis-stealing-witch-related panics, which happened until the mid-20th century in Asia and still happen in Africa. For some reason, this is a classic concern across cultures and centuries. But on the contrary side, God created the human body, and charged Man to be fruitful and multiply. So if the Devil could steal people’s penises it would seem that he must be more powerful than God, which is blasphemous. Kramer answers that witches cannot steal men’s penises, but they can cast an illusion that causes it to look and feel like the penis has been stolen. Classic namby-pamby liberal centrist compromise! Question XIV: The Enormity Of Witches Is Considered, And It Is Shown That The Whole Matter Should Be Rightly Set Forth And Declared This is is one of those “more a comment than a question” questions. Kramer suggests that not only is witchcraft a sin, but it is the worst sin. This section (plus the next few) is a list of all the different things witches are worse than, and why. Witches are worse than pagans, because pagans never knew about Christianity. But witches know about it and deliberately reject it. Witches are worse than Jews, because Jews never claimed to be Christian. But witches were once Christian and then renounced the faith. Witches are worse than ordinary heretics, because ordinary heretics only reject some parts of the faith. But witches implicitly reject all of it by supporting the Devil himself. Witches are worse than Adam, because although Adam’s sin had terrible consequences for the human race, this wasn’t really his direct decision. If we limit our consideration to the specific act, Adam just disobeyed God once, but witches are disobeying God all the time. In fact witches are more sinful than the Devil himself (!), and the Devil’s sin “is in many respects small in comparison with the crimes of witches”. For “both sin against God; but [the Devil] against a commanding God, and [witches] against One who dies for us, Whom, as we have said, wicked witches offend above all.” Witches are literally the worst thing in the entire universe. Whatever else you are concerned about, there is no way it is anywhere close to as bad as witches. If you had the faintest idea how bad witches really were, you would be freaking out all the time. You need to stop whatever you were doing before and become some kind of witch-minimizer instead. This ends Part 1, but if you’re interested you might want to look at further questions from this section, including

…and many more! III: Life’s A Witch, Then You DieThe next section of Malleus moves from the theoretical to the practical. Kramer is an experienced witch hunter who has traveled all over Germany. He knows how witches work. His target audience for this section is some combination of doctors who want to know if a certain malady is witchcraft, villagers who want to know whether they’ve been bewitched, and detectives investigating witch-related crimes. Here is how witches work: first, they make a pact with the Devil. Sometimes this is explicit and involves copulating with demons, other times it’s an “implicit pact” where the woman just sins a lot and doesn’t ask too many questions about where her new powers come from. Although every witch has a slightly different repertoire, typical spells include:

Witch curses most often mimic disease; sometimes physical disease, but often what we would now call mental illness. Chronic pain, psychosis, fatigue, demonic possession. But most of all, erectile dysfunction, because the genital organ has “greater corruption” than other organs of the body. How can a doctor know if a disease is natural vs. witchcraft? The most important thing is to take a good medical history. Ask questions like “Did you offend the old crone by the bog recently?” and “Did she tell you ‘oh, you’ll be getting yours soon enough, hahahckckakaka!’” Witches basically always telegraph their curses with ominous-sounding language, like “You’ll regret offending me!” or “You won’t be feeling so high-and-mighty next week, ohoho!” Any threats like this in the history are pathognomonic for witch-related ailments. Absent this, a doctor will have to use clinical judgment. Is the malady lasting longer than expected? Does it not get cured by first-line treatments like leeches and bloodletting? Is there elevated witch activity in the area? If so, draw your own conclusions. What to do? The easiest solution is to kill the witch responsible. If you can’t kill her, search under your doorstep (and other likely spots) for witch charms; if any are found, remove them. If none of these work, try prayer. It doesn’t always work right away, but usually the right kind of holy action will solve the problem. A typical example is in the chapter on erectile dysfunction, where Kramer recommends:

Is it okay to ask other witches to undo the curse of the first witch? Is a good guy with a witch the only way to stop a bad guy with a witch? Kramer spends a lot of thought on this question, in a way that suggests basically everyone in medieval Germany knows at least one witch, and that asking her for advice is most people’s obvious first step. But he concludes that no, this is sinful, we need a full boycott on all witches including supposedly “good” ones. However, ordinary wise women are okay. You can tell a (good) wise woman from a (bad) witch because the wise woman lives a virtuous life, doesn’t invoke devils in her healing rituals, and probably relies on God in some way. Highlights from this section include: Question I: Of Those Against Whom The Power Of Witches Availeth Not At All Some people are immune to witchcraft. The most notable such group are witch-hunters and judges at witch trials. Witch hunters naturally incur the enmity of witches, so without protection all witch hunters would meet a quick bad end. But God, who hates witches more than anything in the world, realizes this, so in order to incentivize witch hunting He grants witch hunters qualified immunity to all black magic. Skeptical? Kramer has proof:

Also:

Other people protected against witchcraft include very holy people and those who use certain charms or hear certain sacred words. Kramer has strong scientific evidence for this claim too:

Subchapter II: Of The Way Whereby A Formal Pact With Evil Is Made Witches can make two kinds of pacts with the Devil. One kind is relatively low-key: the Devil just kind of appears to them somewhere and asks for their allegiance, and they say yes. The second is more formal, and grants access to more spells. It goes:

As usual, Kramer cites his sources carefully:

Subchapter VII: How, As It Were, They Deprive Men Of His Virile Member Yup, it’s another section on penis-stealing. Kramer keeps coming back to this subject - not, of course, out of any weird obsession on his part, but because witches just keep doing this, and he as a witch-hunter is duty-bound to be prepared. For example:

My favorite part of this story is the guy going to a bar and asking women “hey, my penis was stolen by a witch, wanna see?” I think this could be the next hot trend in pickup artistry. And hold on to your seat, this next paragraph is quite a ride:

Whatever my case was, I hereby rest it. Also interesting in Part 2: IV: Witches Get StitchesAt last we reach witch trials. Witch trials are preferably conducted in the courts of the Inquisition, but secular courts may conduct them when needed, since witches also do secular harm (eg kill cattle). When overseen by the Inquisition, witchcraft is treated as an especially vile subspecies of heresy, and the normal rules for heresy trials apply. On paper, Kramer and the system he represents are very concerned about protecting the innocent. “The proof of an accusation,” he writes, “ought to be clearer than daylight; and especially ought this to be so in the case of the grave charge of heresy”. How do you prove an accusation? Kramer’s preferred method is with at least three witnesses (although judges are permitted to occasionally convict with fewer). Who may serve as a witness? Kramer thinks about this pretty hard. It would seem that maybe the suspect’s enemies should not be allowed to testify against her, because they might be motivated by grudges. On the contrary side, most witches are people of bad reputation who have alienated their whole village, on account of all the witching they do. It would hardly be fair if a suspected witch had to be set free because everyone hated them and no non-enemy could be found to testify. So Kramer compromises again: enemies may testify, but not mortal enemies. A person is considered a mortal enemy of a suspect if one of them has tried to kill the other, or their families have a blood feud, or something of that nature. Should suspects be able to confront the witnesses who testify against them? Kramer recognizes that it would be unfair if they couldn’t. But he’s also concerned about retribution; snitching on a witch to the Inquisition sounds like a one way ticket to Curseville. He concludes that if a witness is scared that they might be harmed if their identity is revealed, their identity should be kept a secret, WHICH BY THE WAY MEANS THAT THE F@#KING INQUISITION HAS MORE PRINCIPLES THAN THE NEW YORK TIMES. I find this solution unsatisfying, but given Kramer’s premises I’m not sure I know a better option (although if there was one, we could call it the Witchness Protection Program). These two decisions lead to a new problem: witch hunters are nomadic types. They don’t know who is mortal enemies with whom in every little village. So suppose so-and-so testifies against a witch. The Inquisitor asks “Are you this woman’s mortal enemy?”, and the witness of course says no. Without asking the suspect to confirm, how do we know if he’s lying? But if we do ask the suspect, how do we prevent her from knowing he’s the witness? Kramer’s proposed solution is to ask the suspect to list off all her mortal enemies; if she names the witness, something is afoot. (Some of you may have already noticed a loophole here. A History Of The Inquisition In Spain describes the case of one Gaspar Torralba, accused in 1531: “There were thirty-five witnesses against him, for he was generally hated and feared. In his defence he enumerated no less than a hundred and fifty-two persons, including his wife and daughter, as his mortal enemies, and he gave the reason in each case which amply justified their enmity . . . The tribunal evidently recognized the nature of the accusation; he was admitted to bail, July 1, 1532, and finally escaped with a moderate penance.”) So you have your three witnesses. You’ve questioned them separately, to see if their stories match, then questioned the suspect separately a bunch of times to see if she changes her story. All the witnesses agree, and the suspect still seems suspicious. Now you can burn her as a witch, right? Wrong. The Holy Inquisition is forbidden to burn anyone as a witch until they confess with their own lips, and confessions obtained under torture don’t count. THIS IS AN EXTREMELY FAKE RULE. The first way it is fake: a confession obtained under torture doesn’t count, but you can torture the witch, let her confess during the torture, and then later, after the torture is over, say “Okay, you confessed, so obviously you’re a witch, please confirm”. If she doesn’t confirm, you can torture her more and repeat the process. The second way it is fake is that you are allowed to lie to her in basically any way to make her confess. Kramer recommends saying “If you confess, I won’t sentence you to any punishment”. Then when she confesses, you hand her over to a different judge for the sentencing phase, and he sentences her to the punishment. Or a judge can promise mercy, “with the mental reservation that he means he will be merciful to himself or the State, for whatever is done for the safety of the State is merciful”. You may, if you wish, transport the suspect to some kind of weird far-off castle (this is the Middle Ages, they have so many weird far-off castles they don’t know what to do with them). Keep her there for a while until she thinks everyone has forgotten about her and the witch trial is over. Have all the ladies and servants of the castle be very friendly to her. One day the lord of the castle will be gone on some errand, and one of the ladies who has befriended her will say: I hear you were a witch once, I really need to bewitch someone, would you mind telling me how to cast a spell? And everyone there has always been so nice, and the witch trial is long forgotten, so she’ll say yeah, sure, and explain how to cause a hailstorm or something. And then you can jump out from behind a tapestry or something and say “Ha! We got you!” Does this really work?

Caught red-handed! The third and final way this rule is extremely fake is that, if none of this makes the suspect confess, the judge can turn her over to the secular courts to be tried for witchcraft-as-a-secular-crime. He is supposed to recommend mercy, but realistically the secular courts will kill her anyway. So do all witch trials end in death? No. If a judge wants a witch trial to end in death, he has plenty of ways to make it happen. But the Malleus gives a list of scenarios (some evidence + no witnesses; some evidence + many witnesses, etc, etc) and most end in “acquittal”. I use the quotes because there is one more hurdle: a ritual called “purgation”, where the suspect brings X witnesses of her same station (eg lord for lord, peasant for peasant) to the town square. There, the witnesses publicly vouch for her good character, and she swears that she is not a witch and forsakes all witchcraft forever. Then everything’s good - but the key is that the more suspicious you seem, the higher the judge will set X. And if you can’t find X people to vouch for your good character, you’re in contempt of court and probably a witch. Also, except in the most cut-and-dry cases of innocence, suspects are released on something like probation: any further accusations of witchcraft will be taken much more seriously. Since people were already willing to falsely accuse you of witchcraft once, good luck with the probation, I guess. Other highlights of this section: Question IX: What Kind Of Defense May Be Allowed, And Of The Appointment Of An Advocate All suspected witches have the right to an attorney. But if the attorney goes overboard defending the client, it is reasonable to suspect him of being a witch himself. Question XVII: Of Common Purgation, And Especially Of The Trial Of Red-Hot Iron, To Which Witches Appeal It might seem that you should give witches trial by ordeal, because that way God can decide their guilt or innocence, and (as has already been established), God really hates witches. The most common trial by ordeal is the trial by iron, where the suspect must hold a red hot iron, and if she drops it, she’s guilty. Unfortunately, witches can use witchcraft to hold the iron, so this doesn’t work. Witches always ask for this kind of trial and are always found innocent, so best to give them a normal trial with witnesses and stuff. Question XXII: Of The Third Kind Of Sentence, To Be Pronounced On One Who Is Defamed, And Who Is To Be Put To The Question Kramer advises: “Let not the Judge be too willing to subject a person to torture, for this should only be resorted to in default of other proofs”. He then goes on to explain that torture usually doesn’t work, because “some are so soft-hearted and feeble-minded that at the least torture they will confess anything, whether it be true or not” and “others are so stubborn that, however much they be tortured, the truth is not to be had from them.” But his conclusion is only that “there is need for much prudence in the matter of torture”, and he goes on to talk a lot about how to torture people. He seems to think of false confessions (and false silence) as minor issues that deserve some attention but shouldn’t keep a judge from torturing someone if he really wants. It’s actually worse than this, because he goes on to say that the Devil often makes witches immune to torture. If someone doesn’t seem to mind being tortured at all, they’re probably a witch. If someone doesn’t cry when being tortured, that’s another red flag, because witches can’t cry (source: everyone knows this). To Kramer’s credit, he is willing to follow the logical implications of his belief: he agrees that if a suspect does cry, that means she’s innocent. Being really mean, trying to make her cry, and then letting her go if she does is . . . actually a valid witch trial method! But you have to be careful: sometimes witches try to game the system by carrying a concealed pouch of noxious herbs to make their eyes tear up. You should only release someone for crying if you’re sure they haven’t done this. Also interesting in Part 3: V: Who Witches The Witchmen?So ends the Malleus Maleficarum, returning us to our original question: what were these people thinking? I worry I haven’t fully captured the spirit of the Malleus in this review. For space reasons, I omitted most of the many, many times when Kramer follows his claims with stories of the cases that led him to believe them. For example, after asserting that witches kill farm animals by planting evil charms under the dirt near their barns, he says:

Everything is like this. Rare is the unsourced claim. If we moderns cited our sources half as often as the Malleus Maleficarum, the world would be a better place. So what’s going on? Theory 1, Kramer made everything up. I don’t want to completely discount this. There must be at least one pathological liar in 15th century Europe, and surely that would be the kind of person who would write the world’s most shocking book on witches and start a centuries-long panic. Against this proposal, he sometimes names specific sources who a fact-checker could presumably go talk to, or specific court cases that living people must remember. I’ll stop here before we start retreading the usual arguments around the Gospels, etc. Theory 2, Kramer is faithfully reporting a weird mass hallucination that had been going on long before he entered the picture. You can imagine a modern journalist interviewing UFO abductees or something. Some consistent rules might emerge - the spacecraft are always saucer-shaped, the aliens always have big eyes - but only because pre-existing legends have shaped the form of the hallucinations and lies. Then, unless he’s really careful, he unconsciously massages the data and adds an extra layer of consistency, until it everything makes total sense and seems incontrovertible. I think 2 is basically right - again, I refer interested readers to Frank Boles’ study of penis-stealing-witch traditions around the world. Wherever there are superstitious people, there will be stories about witches, which will cohere into a consistent mythos. Add a legal system centered around getting people to confess under torture, and lots of people will confess. And since confessed witches were judged more repentant if they explained to the judge exactly what they did and maybe incriminated others, they’ll make up detailed stories about entire covens, and these stories will always match what their interlocutors expect to hear - ie the contours of the witch myth as it existed at the time. And what about false memories? During the Satanic Panic, lots of people ended up convinced they were abused by Satanic cults as children, even though further investigation suggested this never happened. Psychologists examining these people would accidentally implant false memories (“And did the man who abused you have a pentagram tattooed on his head?” “Hmmm….yes…it’s breaking through the fog of repression…yes! Yes he did!”) Maybe illiterate medieval peasant women had low will saves, and prestigious Inquisitors could make them believe pretty much anything. (And I don’t want to completely rule out that some people actually tried witchcraft. If you live the horrible life of a medieval peasant woman, and you hear that making a pact with the Devil gives you amazing magic powers that let you take revenge on all your enemies, maybe you start invoking the Devil. The history of modern occultism implies that any sufficiently schizo-spectrum person who asks to see the Devil will come away satisfied. So you see him, thank him, cackle a bit at your neighbor, feel good when some of their cattle die, and then they snitch on you to the Inquisition and you freak out and confess. I don’t know if this ever happened, but nothing I know about human nature rules it out. Honestly it seems less weird than school shooters.) I’m not especially interested in rehabilitating Henry Kramer, at least not in the same way Montague Summers is. But I think there’s a tragic perspective on him. This is a guy who expected the world to make sense. Every town he went to, he met people with stories about witches, people with accusations of witchcraft, and people who - with enough prodding - confessed to being witches. All our modern knowledge about psychology and moral panics was centuries away. Our modern liberal philosophy, with its sensitivity to “people in positions of power” and to the way that cultures and expectations and stress under questioning shape people’s responses - was centuries away. If you don’t know any of these things, and you just expect the world to make sense, it’s hard to imagine that hundreds of people telling you telling stories about witches are all lying. The section on trials felt like the same error mode. Kramer emphasized many times that you need to interview all witnesses and the suspect several times, many days apart, using slightly different questions each time, to catch inconsistencies. There is something admirable in this. He is clearly trying. Nowadays, with the benefit of hundreds of years of psychological research, we know that memory is slippery, especially under stress, and even honest people often change their story for no reason. But when some suspect told Kramer she was out at the barn when the alleged bewitchment occurred, and then the next day she said no, she was out in the forest, he must have considered it a job well done as he consigned her to the flames. Or false confession! I remember my high school psychology class, how boggled I was when I learned lots of people often confess falsely, even when they’re not under torture or being pressured or anything. This still boggles me. I accept it, because I’ve read many smart people with personal experience saying it’s true, but I won’t claim it makes sense. Kramer never had any of that literature. He is rightfully suspicious of confessions obtained under torture, but how should he have known that even freely given confessions can be dubious? So I think of Henry Kramer as basically a reasonable guy, a guy who expected the world to make sense, marooned in a century that hadn’t developed enough psychological sophistication for him to do anything other than shoot himself in the foot again and again. This is how I think of myself too. As a psychiatrist, people are constantly asking me questions about schizophrenia, depression, chronic fatigue, chronic Lyme, chronic pain, gender dysphoria, trauma, brain fog, anorexia, and all the other things that the shiny diploma on my wall claims that I’m an expert in. In five hundred years, I think we’ll be a lot wiser and maybe have the concepts we need to deal with all of this. For now, I do my best with what I have. But I can’t shake the feeling that sometimes I’m doing harm (and doing nothing when I should do something is a kind of harm!) They say the oldest and strongest fear is the fear of the unknown. I am not afraid of witches. But I am afraid of what they represent about the unknowability of the world. Somewhere out there, there still lurk pitfalls in our common-sensical and well-intentioned thought processes, maybe just as dark and dangerous as the ones that made Henry Kramer devote his life to eradicating a scourge that didn’t exist. Happy Halloween! You’re a free subscriber to Astral Codex Ten. For the full experience, become a paid subscriber. |

Older messages

Nick Cammarata On Jhana

Thursday, October 27, 2022

...

Open Thread 247.5

Thursday, October 27, 2022

...

Highlights From The Comments On Supplement Labeling

Wednesday, October 26, 2022

...

From The Mailbag

Tuesday, October 25, 2022

Answers to the questions I get asked most often at meetup AMAs

Open Thread 247

Monday, October 24, 2022

...

You Might Also Like

10 Things That Delighted Us Last Week: From Seafoam-Green Tights to June Squibb’s Laundry Basket

Sunday, March 9, 2025

Plus: Half off CosRx's Snail Mucin Essence (today only!) The Strategist Logo Every product is independently selected by editors. If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an

🥣 Cereal Of The Damned 😈

Sunday, March 9, 2025

Wall Street corrupts an affordable housing program, hopeful parents lose embryos, dangers lurk in your pantry, and more from The Lever this week. 🥣 Cereal Of The Damned 😈 By The Lever • 9 Mar 2025 View

The Sunday — March 9

Sunday, March 9, 2025

This is the Tangle Sunday Edition, a brief roundup of our independent politics coverage plus some extra features for your Sunday morning reading. What the right is doodling. Steve Kelley | Creators

☕ Chance of clouds

Sunday, March 9, 2025

What is the future of weather forecasting? March 09, 2025 View Online | Sign Up | Shop Morning Brew Presented By Fatty15 Takashi Aoyama/Getty Images BROWSING Classifieds banner image The wackiest

Federal Leakers, Egg Investigations, and the Toughest Tongue Twister

Sunday, March 9, 2025

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said Friday that DHS has identified two “criminal leakers” within its ranks and will refer them to the Department of Justice for felony prosecutions. ͏ ͏ ͏

Strategic Bitcoin Reserve And Digital Asset Stockpile | White House Crypto Summit

Saturday, March 8, 2025

Trump's new executive order mandates a comprehensive accounting of federal digital asset holdings. Forbes START INVESTING • Newsletters • MyForbes Presented by Nina Bambysheva Staff Writer, Forbes

Researchers rally for science in Seattle | Rad Power Bikes CEO departs

Saturday, March 8, 2025

What Alexa+ means for Amazon and its users ADVERTISEMENT GeekWire SPONSOR MESSAGE: Revisit defining moments, explore new challenges, and get a glimpse into what lies ahead for one of the world's

Survived Current

Saturday, March 8, 2025

Today, enjoy our audio and video picks Survived Current By Caroline Crampton • 8 Mar 2025 View in browser View in browser The full Browser recommends five articles, a video and a podcast. Today, enjoy

Daylight saving time can undermine your health and productivity

Saturday, March 8, 2025

+ aftermath of 19th-century pardons for insurrectionists

I Designed the Levi’s Ribcage Jeans

Saturday, March 8, 2025

Plus: What June Squibb can't live without. The Strategist Every product is independently selected by editors. If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an affiliate commission.