Hi there, it’s Mehdi Yacoubi, co-founder at Vital, and this is The Long Game Newsletter. To receive it in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

In this episode, we explore:

How scientists want to make you young again

Measuring well-being and not economic productivity

When disaster strikes

The Bill Gurley chronicles

Let’s dive in!

Interested in what 'cellular rejuvenation' and Altos Labs is all about? Here's a great article exploring reprogramming technology with Yamanaka factors.

A little over 15 years ago, scientists at Kyoto University in Japan made a remarkable discovery. When they added just four proteins to a skin cell and waited about two weeks, some of the cells underwent an unexpected and astounding transformation: they became young again. They turned into stem cells almost identical to the kind found in a days-old embryo, just beginning life’s journey.

At least in a petri dish, researchers using the procedure can take withered skin cells from a 101-year-old and rewind them so they act as if they’d never aged at all.

Now, after more than a decade of studying and tweaking so-called cellular reprogramming, a number of biotech companies and research labs say they have tantalizing hints the process could be the gateway to an unprecedented new technology for age reversal. By applying limited, controlled doses of the reprogramming proteins to lab animals, the scientists say, they are seeing evidence that the procedure makes the animals—or at least some of their organs—more youthful.

“There is no reason we couldn’t live 200 years.”

To be sure, the word “rejuvenation” sounds suspicious, like a conquistador’s quest or a promise made on a bottle of high-priced face cream. Yet rejuvenation is all around us, if you look. Millions of babies are born every year from the aging sperm and egg cells of their parents. Cloning of animals is another example. When Barbra Streisand had her 14-year-old dog cloned, cells from its mouth and stomach were returned to her as two frolicking puppies. These are all examples of cells being reprogrammed from age to youth—exactly the phenomenon companies like Altos want to capture, bottle, and one day sell.

For now, no one has a firm idea what these future treatments could look like. Some say they will be genetic therapies added to people’s DNA; others expect it’s possible to discover chemical pills that do the job. One proponent of the technology, David Sinclair, who runs an aging-research lab at Harvard University, says it could allow people to live much longer than they do today. “I predict one day it will be normal to go to a doctor and get a prescription for a medicine that will take you back a decade,” Sinclair said at the same California event. “There is no reason we couldn’t live 200 years.”

It’s this type of claim that raises so much skepticism. Critics see ballooning hype, runaway egos, and science that’s on uncertain ground. But the doubters this year were drowned out by the sound of stampeding investors. In addition to Altos, whose $3 billion ranked as possibly the single largest startup fundraising drive in biotech history, the cryptocurrency billionaire Brian Armstrong, the cofounder of Coinbase, helped bring $105 million into his own reprogramming company, NewLimit, whose mission he says is “radical extension of human health span.” Retro Biosciences, which says it wants to “increase healthy human lifespan by 10 years,” raised $180 million.

These huge expenditures are being made despite the fact that scientists still disagree on the causes of aging. Indeed, there’s no real consensus on when in life aging even begins. Some say it starts at conception, while others think it’s at birth or after puberty.

Pair with:

I liked this thought-provoking piece calling for measuring well-being instead of economic productivity.

First, economic measurement is largely “voodoo.”

How is economic productivity calculated? Roughly speaking, to calculate "labor productivity" one looks at stuff like

There are also more general notions like "multifactor productivity", i.e.

how much of other inputs besides human-hours (physical equipment, invention, education, etc.) does it take to produce a certain unit of product?

I'll focus mostly here on labor productivity but the same basic points apply to multifactor.

Why Not Measure Catalysis of Well-Being Instead?

Given all the complexities and hassles involved in measuring economic productivity beyond a diminishing set of cases where product unit definitions have remained fairly constant over time, one might wonder whether it's really a worthwhile thing to be doing.

The "hedonic corrections" used to figure out how much more valuable a modern high-def TV is than an 1980 TV or a 1970 black and white TV, may actually point the way toward something more interesting to measure.

Rather than making up a questionably-derived fudge-factor to estimate how much more "hedonically valuable" or "fundamentally valuable" a new TV is than an old one, what if we took this notion of hedonic value more seriously? This could let us measure economic productivity more meaningfully, and also have some more interesting uses as well.

How might we do this? Psychology, data, statistics and a bit of machine learning can be our friends here.

One could use this sort of well-being-estimate to come up with more meaningfully humanly grounded "hedonic correction" numbers to estimate the human value of a high-def TV versus an old TV. But in the end this only solves a fraction of the problem with the typical notion of labor productivity -- it doesn't help with measuring the productivity of employees of Facebook or Spotify, for example.

Given the nature of the modern economy, what makes most sense is to give up on old notions of economic productivity, except in particular legacy sectors, and focus instead of understanding the impact of various activities on human well-being.

Doing this sort of systematic measurement would, however, expose a lot of issues more important than the ups and downs of economic growth and efficiency. It would expose the fact that a lot of what goes on in the modern economy actually decreases human well-being.

And this could lead to a different direction for economic policy than what’s currently dominant in most major nations. What if the government were to direct a certain percentage of collective resources specifically toward products and services found to increase well-being, and away from those found to decrease well-being? A pure libertarian philosophy would view this as overly paternalistic and intrusive, but the same "democratic socialist lite" philosophy that we have in modern democracies — the philosophy that has led us to public education, public libraries, national parks, carbon credits and (in every developed country but the US) robust public health care —would naturally lead to this sort of policy initiative.

Pair with: Happiness and Life Satisfaction

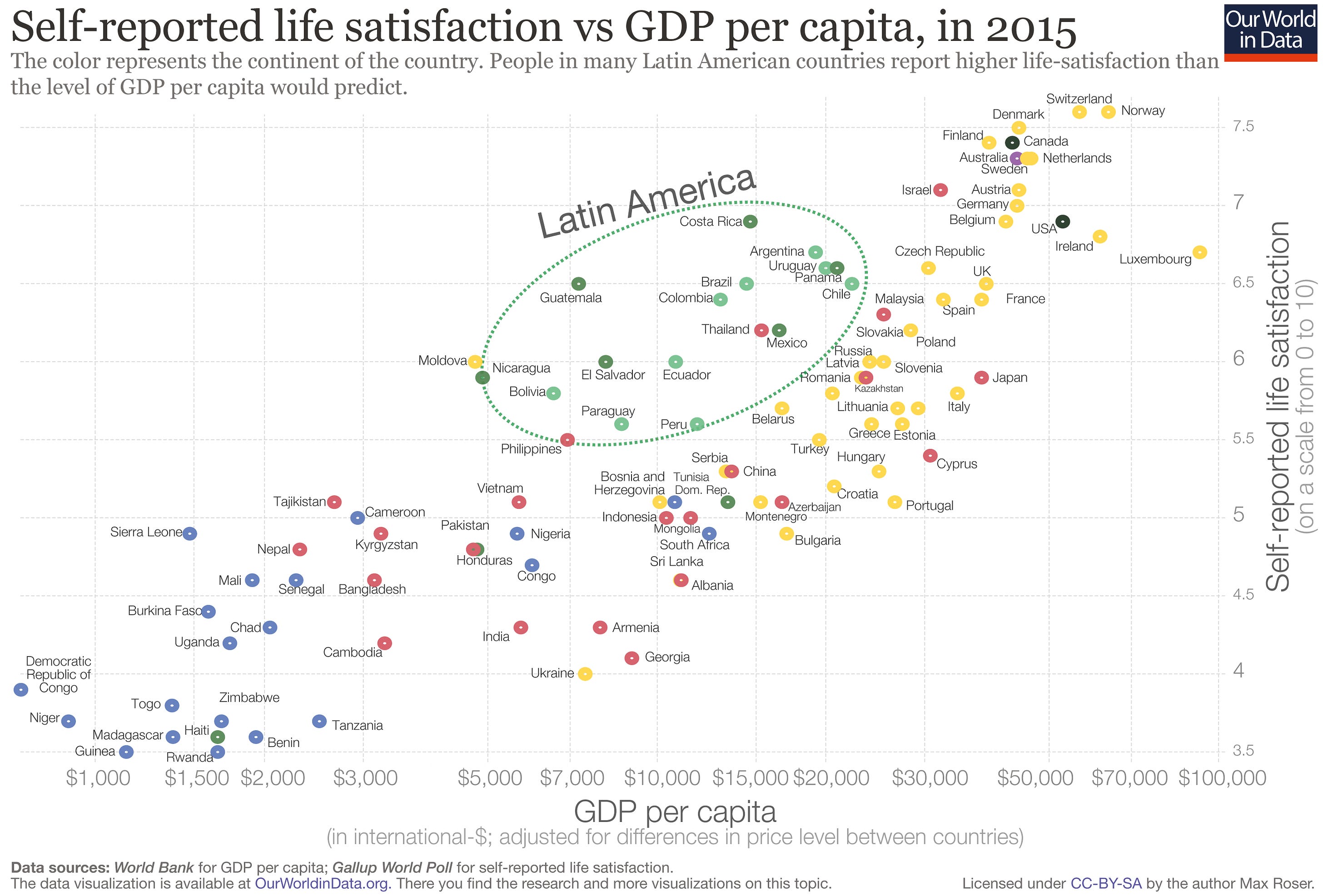

Comparisons of happiness among countries suggest that culture and history shared by people in a given society matter for self-reported life satisfaction. For example, as the chart here shows, culturally and historically similar Latin American countries have a higher subjective well-being than other countries with comparable levels of economic development. (This chart plots self-reported life satisfaction as measured in the 10-point Cantril ladder in the vertical axis, against GDP per capita in the horizontal axis).

Latin America is not a special case in this respect. Ex-communist countries, for example, tend to have lower subjective well-being than other countries with comparable characteristics and levels of economic development.

Academic studies in positive psychology discuss other patterns. Diener and Suh (2002) write: “In recent years cultural differences in subjective well-being have been explored, with a realization that there are profound differences in what makes people happy. Self-esteem, for example, is less strongly associated with life satisfaction, and extraversion is less strongly associated with pleasant affect in collectivist cultures than in individualist cultures”.

To our knowledge, there are no rigorous studies exploring the causal mechanisms linking culture and happiness. However, it seems natural to expect that cultural factors shape the way people collectively understand happiness and the meaning of life.

I enjoyed this interview with Michael Story on forecasting.

Suppose I come to you with a forecasting question on a topic that you know next to nothing about - what is your process for researching the question, and is there anything particularly unique that you do that you think other (super)forecasters could learn from?

There is a standard ‘set’ of techniques most forecasters use when encountering something new. They’d first look at the base rate of similar incidents in the past, giving them the “outside view” starting estimate of the probabilities involved. Then they’d look at the specific mechanisms by which an event of this type might occur, considering the time and event scale carefully. They’d review a bunch of different sources to adjust their estimate and finally conduct a “pre mortem”- answering the question “how am I most likely to have been wrong?”.

These are the likely common answers which are a useful staring point but there’s a lot more going on among forecasters than people deploying this process. Many people have their own individual methods and practices which work with the grain of their brains, even down to the level of intuition, but because those things are specific to people, they wouldn’t turn up in a big survey. Having said that, ‘classic’ forecasting techniques are classic because they work.

The most important thing to think about when forecasting is calibration. You might start out using a number of different techniques or even ‘trusting your gut’ and intuition, but if you don’t measure your accuracy and see what causes it to improve, you’re really not going to get better.

I do believe there is a neurodiversity component to this as well. In my experience, one of the reasons that forecasters can get things right is that they tend to be a little less influenced by social information. If you’re not very swayed by social trends or the prevailing views, then you have a big advantage in being able to dispassionately apply some the standard techniques outlined above. I think this accounts at least in part for things appearing a bit more ‘obvious in retrospect’, when they’re stripped of the social and emotional context.

There probably aren’t any techniques that I use that I’ve never heard of anyone else using. One area where I’ve been able to get better results than I otherwise would have done is figure out where there might be weaknesses in the crowd prediction. I’m good at identifying where other people have gone completely wrong. For instance, I might be able to develop a mental model about whether the crowd is likely to overestimate or underestimate the chance that some country is likely to start a war. You can quantify the group-think there: if I think people’s mental models make people likely to think the country is 10% more likely to be belligerent, I can adjust from there.

Just an important reminder for this week: when disaster strikes, don’t quit. And as a startup, you can be 100% certain that disaster will strike often.

So I'll tell you now: bad shit is coming. It always is in a startup.

The odds of getting from launch to liquidity without some kind of disaster happening are one in a thousand.

So don't get demoralized.

When the disaster strikes, just say to yourself, ok, this was what Paul was talking about. What did he say to do? Oh, yeah. Don't give up.

On the decline of genius:

I think the most depressing fact about humanity is that during the 2000s most of the world was handed essentially free access to the entirety of knowledge and that didn’t trigger a golden age.

Think about the advent of the internet long enough and it seems impossible to not start throwing away preconceptions about how genius is produced. If genius were just a matter of genetic ability, then in the past century, as the world’s population increased dramatically, and as mass education skyrocketed, and as racial and gender barriers came thundering down across the globe, and particularly in the last few decades as free information saturated our society, we should have seen a genius boom—an efflorescence of the best mathematicians, the greatest scientists, the most awe-inspiring artists.

If a renaissance be too grand for you, will you at least admit we should have expected some sort of a bump?

And yet, this great real-world experiment has seen, not just no effect, but perhaps the exact opposite effect of a decline of genius. Consider how rare true world-historic geniuses are now-a-days, and how different it was in the past. In “Where Have All the Great Books Gone?” Tanner Greer uses Oswald Spengler, the original chronicler of the decline of genius back in 1914, to point out our current genius downturn.

Pair with: The mystery of the miracle year

On the challenges of high speed rail:

Despite my ongoing enthusiasm for HSR, I have to concede that it is not a universal panacea. It remains relatively niche and relatively undeveloped. It is possible that its failure to be deployed everywhere since it was first developed 50 years ago is due to short-sighted governments and cost disease (the tendency for modern construction within developed cities to cost much much more than the original project did historically), but other factors also contribute to its lack of competitiveness.

To illustrate this, let’s examine past and current HSR development.

Despite decades of development, only a handful of routes in Europe operate at anything like airplane-competitive speeds, which for all but the shortest routes, require > 300 km/h or > 185 mph.

Pair with: The Myth of Chinese Efficiency

“I know that I’m living a life I like. There’s a certain terror to that. Because I’m scared I’ll lose it. But I keep thinking: if I appreciate the time I have, I’ll be able to look back and say I paid attention to everything I could.”

For most of my life I wanted things to go faster. Last week, I realized that now I want things to slow down. That change seems meaningful. I don’t know what’s catalyzed it—getting older, probably. Feeling that I’m finally headed in the right direction. Mindfulness? Whatever it is, I’ve noticed that the present seems more bearable.

Back when I was feeling aimless and lost I used to read and reread something Cheryl Strayed wrote about writing:

The useless days will add up to something. The shitty waitressing jobs. The hours writing in your journal. The long meandering walks. The hours reading poetry and story collections and novels and dead people’s diaries and wondering about sex and God and whether you should shave under your arms or not. These things are your becoming.

Back then, I wanted to believe it, but I wasn’t sure. Now I know that it’s true. Time seems more precious, because I know that every moment matters. Everything adds up.

A critical point has been reached; decoupling is for real this time.

In fact, whether the non-China bloc coordinates on policy is really the big question regarding the new world-economic order. Together, the U.S., Europe, and the rich democracies of East Asia comprise a manufacturing bloc that can match China’s output and a technological bloc that can exceed China’s capabilities. With the vast populations of India and other friendly developing countries on their side, they can create a trading and production bloc that will be almost as efficient as the old Chimerica system. But this will take coordination and trust on economic policy that has been notably absent so far. The U.S. will have to put aside its worries about competition with Japan, Korea, Germany or Taiwan — and vice versa.

In any case, this vision — a largely but not completely bifurcated global system of production and trade, with two technologically advanced high-output blocs competing head to head — seems like the most likely replacement for the Chimerica system that dominated the global economy over the past two decades. But it’s only a loose guess. What’s not really in doubt here is that we’ve reached a watershed moment in the history of the global economy; the system we came to know and rely on over the past two decades is crumbling, and our leaders and thinkers need to be scrambling to plan what comes next.

Bill Gurley is a legendary venture capital investor and a great thinker. His blog covers valuable insights on VC investing, valuations, growth, and marketplace business.

This document summarizes every blog post Gurley has ever written. It’s a gold mine.

October 18, 1999: The Rising Importance Of The Great Art Of Storytelling

Summary: Storytelling is one of the most underappreciated business skills. Bill Gates admired a man (Craig McCaw) because he was able to convince investors to invest in a capital-heavy infrastructure business. McCaw created new (proxy) valuations to sell the story the company was trying to deliver. Storytelling also gets a bad rap because it’s associated with “hype” — overpromising and under delivering. Recognizing a good story from a bad one helps investors avoid dreams and invest in the future.

Favorite Quote: “As public market investors begin to evaluate younger and younger companies, their valuation tools become limited to subjective notions such as quality of the team and the uniqueness and boldness of the idea. In other words, if there isn’t enough proof that a business already exists, then they must make a judgment as to whether one will.”

Pair with: The Complete Strength Training Guide

I enjoyed 18 months of intense training injury free, and lately, I’ve felt that I should pay more attention to my recovery to prevent future injuries. There’s a lot to say about training hard and staying injury-free, but I’ll keep that for another day.

I started exploring massage guns as a way to recover faster, boost my circulation and lymphatic drainage, increase my flexibility and extend my range of motion – ultimately boosting performance across the board.

I haven’t bought one yet, but here are some good options at multiple price points.

Send me some recovery resources/recommendations if you have some! 💌

People think focus means saying yes to the thing you've got to focus on. But that's not what it means at all. It means saying no to the hundred other good ideas that there are.

— Steve Jobs

Thanks for reading!

If you like The Long Game, please share it on social media or forward this email to someone who might enjoy it. You can also “like” this newsletter by clicking the ❤️ just below, which helps me get visibility on Substack.

Until next week,

Mehdi Yacoubi