Computer-generated art comes from data. But where does human art come from?BB-2 drudges through a seemingly endless flow of cybernetic imagery. Nature photographs; beautiful New Mexican scenery; a naturalist’s observation of a glassy-tiger butterfly. Every datum is chewed on, digested, and added by the machine to its internal database. The glassy tiger is not a tiger, BB-2 notes. All this cybernetic imagery goes into processing phrases that humans type in. BB-2’s job is to take these phrases and, using its bank of cybernetic imagery, translate them into electronic art pieces. Who knows what the humans will type next? the machine thinks to itself, “Man riding a bicycle”, “Swan Upon Leda”, or “Martin Heidegger making out with Hannah Arendt”? BB-2 is not alone. There are many AI or Artificial Intelligence engines that can generate artwork. Some, such as the now popular DALL-E can create works that incorporate the styles, moods, and tones from different real artists of the past—including Salvador Dalí, the artist that DALL-E is named after. Does this new development mean the end of artists as we know them? For those who just want an image to stick on top of their blog posts, maybe—but stock photos had already taken that space. What about those who appreciate real, authentic art? Can AI art truly be considered real and or authentic art? These questions tread into philosophical territory, and perhaps are answered by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzche who also sought to answer the question: where does art come from?

As a philologist Nietzsche studied Greek and Roman literature, Nietzche’s first published work was upon the origins of the classical Athenian tragedy entitled The Birth of Tragedy out of the Spirit of Music. But as he traced through the history of Athenian tragedy, parallels were also found between these tragedies and other, different, forms of art. Nietzche devised two energies found in the creation of art; energies which he credited to gods. There is the Apolloian, whose energy is ordered, set, and rational in nature. And then there’s the Dionysian, which, being the opposite of the Apolloian, has an energy that is chaotic and ever altering. Apollonian work is systematic and calculated, whereas the Dionysian is driven by emotion and ecstasy! The way Nietzsche saw it, the Greek gods of Apollo or Dionysus would first reveal themselves to the artist who, frenzied by the godly energy, would go about the creation of art. An artist is one who is able to capture the Apollonian and Dionysian frenzies and then manifest these energies into art.

One should note here that though he references gods, Nietzsche himself did not believe in any god by the time of his writing. After all, Nietzsche famously wrote that “God is dead!” What Nietszche meant was that God existed because we believed in Him. But as religion lost importance in various spheres of life, people stopped believing in Him, which means, according to Nietzsche, that He effectively ceased to exist. That God is dead to us. Still, according to Nietzsche, it is not only gods but also God who can be defined as an artist. An example of God as an artist can be found in the work of Giovanni Boccaccio. In his time, Boccaccio was a writer so well known that many simply referred to him as “the Certaldese” after his hometown. His work, the Decameron, was written in the aftermath of the Black Death, and revolves around ten people taking refuge from that 14th-century pandemic. Over the course of the fortnight, they tell each other a hundred stories to pass the time—some witty, some tragic, and all containing a slice of life from that time.

Our story of interest begins with an argument about who are the oldest, and therefore most respectable, gentlemen in all of Florence. A young man, Michele Scalza, breaks up this conversation with a claim that it is none of these people but the baronci who are older than anyone else in the world. Baronci in Florentine slang referred to people who took money from other people instead of putting in work themselves, which is why they were looked down upon. “You must know,” goes the explanation, “that the baronci were made by God the Lord in the days when He first began to learn to draw; but the rest of mankind were made after He knew how to draw”. Scalza then goes on to point out how the rest of mankind has well-proportioned faces, whereas the baronci have various defects: a face too broad, a nose too short, or a chin jutting out the wrong way. “Wherefore,” concludes Scalza, “as I have already said, it is abundantly apparent that God the Lord made them, what time He was learning to draw; so that they are more ancient and consequently nobler than the rest of mankind.”

This story of God as an artist from Boccaccio shows that no art exists in isolation. Just as BB-2 and DALL-E draw from cybernetic imagery, so cognizant beings such as Friedrich Nietzsche, Giovanni Boccaccio, and God Himself must draw from joint Apollonian and Dionysian frenzies. Boccaccio’s story showcases that art is a matter of drawing upon. However, even this drawing-upon does not guarantee perfect artistic results. Nietzche’s maiden work, The Birth of Tragedy, may be a much read classic today, but Nietzche himself didn’t think much of it. “Today I find it an impossible book”, he lamented years later. “I consider it badly written, ponderous, embarrassing, image-mad and image-confused...” Such is the plight of the artist, be they Nietzsche writing a book or God creating the baronci: their work, at least in their eyes, never seems complete, because there’s always one more finishing touch to be done. Closer home, the article you are now reading has already gone through three or four revisions. Sadly, it was only the impending deadline that convinced me to leave this work be as it is.

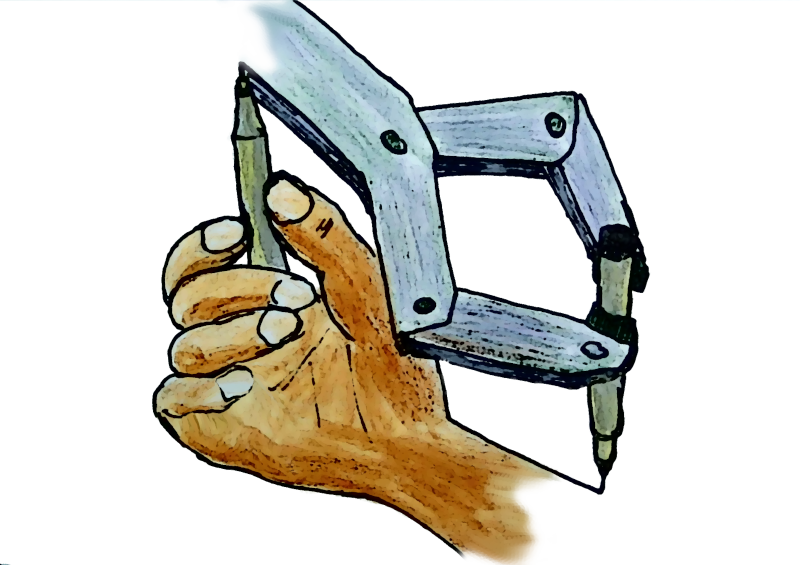

In some ways, the human race thinks of itself in much the same way as an artist does. It looks back on its past thinking, for example, Did we really believe that germs came from miasma? We were so foolish and ignorant back then. With this sort of mindset, humanity tends to look down on any aspect of its past self, a tendency which can also be seen in its constituent parts when a human says I was only a foolish youth back when that happened or wow, the things I got up to when I was little! The early days of the sciences were highly Dionysian, consisting mostly of theory with little experimentation. As time progressed, logic and mathematics took precedence, and the Apollonian came into great control. But in its zeal to leave behind its Dionysian past, humanity has now landed us in a world that is veering more Apollonian still! Scientists use formulas to make more accurate predictions; engineers use them to make better products. Countries rank themselves based on GDP, which is essentially a simple sum of everything spent in the nation. Businesses track numbers and metrics to make sure they’re running smoothly, and now, even art is being generated using AI engines such as DALL-E and BB-2. There is no doubt that the Apollonian side has benefitted us, and we would be far behind without it. But what of the Dionysian?

“A mind all logic”, wrote Bengali philosopher Rabindranath Tagore, “is like a knife all blade. It makes the hand bleed that uses it.” This is not to say that logic, or the Apollonian way, is bad. However, an excess of anything is never good. In pursuing the Apollonian, we have mostly forgotten the other frenzy of the Dionysian. That’s why people have to raise statements these days such as “a person is not just a number” and “GDP doesn’t tell the whole story”. These are not new ideas. After all, it was back in 1968 that Robert Kennedy, brother of the then President of the United States, remarked that the Gross National Product measures everything “...except that which makes life worthwhile”. That said, these are ideas that we as humans are beginning to forget, and, therefore, necessitate repeating. In the art world too, it can be argued that forgetting Dionysus is leading to less energetic and less intoxicating art.

Dionysian art, wrote Professor Aaron Ridley while analysing Nietzche’s work, “gives expressions to the will in its omnipotence…the eternal life behind all phenomena.” Just as God’s creations went on to create art of their own, so today our own creations have begun to create some semblance of art. Mentalities surrounding programs like BB-2 have caused human artists to doubt their power; to lose grip on their connection to godly energies. Indeed, one could ask: are mainframes around strongly Apollonian programs like BB-2 causing mankind to forget where art comes from? However, there still remains a crucial difference: DALL-E and BB-2 miss out on the feeling of error and incompleteness. Once their algorithm runs through, they’re done, and there is no emotional pull drawing them back. This is not true for humans like Nietzche and Boccaccio, who often feel incompleteness, and keep returning to add improvements. As for God—well, God is always working. As a human, perhaps art is telling me something about the nature of God; that God Itself is the un-finish-able. But eventually, like so many other humans before me, I will have to bring my work to a close and deem it done—or be stuck with an unfinished piece forever.

BB-2 drudges through a seemingly endless flow of cybernetic imagery. Nature photographs; beautiful New Mexican scenery; a naturalist’s observation of a glassy-tiger butterfly. Every datum is chewed on, digested, and added by the machine to its internal database. The glassy tiger is not a tiger, BB-2 notes…

The Editors' Bookshelf Badri Sunderarajan

Welcome to The Editors' Bookshelf where you get weekly book recommendations straight from our editors! This week, we have Badri suggesting The Decameron written by Giovanni Boccaccio and translated by John Payne. When you purchase a book through our Bookshop.org link, we earn a small commission. Imagine Arabian Nights or The Canterbury Tales, but from Italy. That’s the Decameron in a nutshell. (In fact, The Decameron is said to have been part of the inspiration behind The Canterbury Tales, and it, along with Arabian Nights, formed a series of films by Pier Paolo Pasolini in 1971). Set in the time of the Black Death, it follows seven ladies and three gentlemen who flee the city of Florence and take refuge in the countryside from the oncoming plague. To pass the time, they take turns in telling each other stories, resulting in ten stories for each of the ten days the book covers, making a hundred in total. Many of these tales have to do with morals and chastity, kings and servants, and the hands of God and fate—which is to say, they are about people from the time in which the book was written. Being originally written in Italian, the version of The Decameron that I read was translated by John Payne—who knew his material well, judging by the many footnotes he left, explaining for our benefit some subtle Italian joke or reference, and sometimes gleefully noting how previous translators got thoroughly confused when they didn’t know what the book was talking about. Since the translation was published back in 1886, it uses a variety of English closer to the Shakespearesque than what we speak today, which meant a lot of words to read through. But that was refreshing in its own way, because, while using language that was very Old English, the culture it spoke of was rather different.

💡 Feeling inspired? Snipette has some awesome authors—and you could be one of them! Whether you're a researcher looking to share your work or a student wanting to write something that isn't homework, our editors have you covered. Join our Writers' Programme for a guided experience, or just submit straight away. |