Hi there, it’s Mehdi Yacoubi, co-founder at Vital, and this is The Long Game Newsletter. To receive it in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Some personal news: I recently became a father. This was, by far, the most fantastic experience of my life. Expect some occasional parenting & kids-related content on The Long Game as I learn what there is to know. So far, I discovered that the education/parenting space is even more controversial and dogmatic than nutrition science, which is hard to do!

In this episode, we explore:

Your Brain on Exercise

Living in Public, Living in Private

Status Monkeys

Rise of the Silicon Valley Small Business

Intensity

Academic freedom at Stanford

Let’s dive in!

I read this article on running & creativity a few weeks ago and was reminded of it after restarting training after the hospital & a slight cold.

Think back to a time when you came up with a creative idea. It might seem like it popped into your mind, fully formed — or dropped into your brain while you were doing something totally unrelated, like taking a shower or going for a run.

Runners in particular often cite the mind-clearing, meditative aspect of hitting the pavement as one of the reasons why they love to run. And in fact, some research does indicate a link between exercise and creative thought: One 2014 Stanford University study found that participants experienced a creative boost after walking on treadmills. Research also supports a larger connection between exercise and brain health, since physical activity can lead to neurogenesis — the creation of new neurons in the part of the brain linked to learning and memory. Exercise has also been linked to other mental benefits like increased neuroplasticity and greater ability to learn, as well as better task-switching ability and improved focus.

Whether it’s creativity or mood, it’s worth repeating that moving your body (no matter how, run, walk, lift, etc.) will fundamentally impact how you feel and what you’re capable of. The good news is that this can be repeated multiple times per day; I like a 20/30 min walk whenever I start to feel a bit off.

This way, it’s very hard to feel bad for prolonged periods.

Once you become aware of the impact that running can have on your mind, Mannino says you might even be able to use running to harness a flow state purposefully. If you know that going for a challenging run can help you enter flow — and therefore, prime your brain to think creatively — you can use that mental state to really meditate on a problem you want to solve, or come up with a fresh idea. “Cognition is grounded in movement, and movement is required for cognition,” he says. “If we use movement in very organized ways like running, then we get a lot of bang for our buck in terms of the effects on mental wellness and cognition.” Plus, flow just feels good: it refocuses your thoughts away from worries and stress, and can even help guard against work-related burnout.

In other words, getting into flow for the sake of it can be beneficial — much like creativity. Gabora sees the creative process as an accomplishment in and of itself, whether or not you produce a physical work like a painting, musical composition, or invention. “What really matters is that you are actually changed by the creative process,” she says. Thinking creatively can change how you see yourself as well as the world around you, potentially altering your worldview and setting the stage for future creativity. Consider practicing creativity the same way as going for a run: You might not achieve a personal record every time you lace up your sneakers, but each step you take trains your muscles for the next run.

I found this essay captured very well the intricacies of living in public vs. living in private.

Living in public, when done sincerely, is worse for you, but better for other people.

Let me back up.

"I really would like to have the film rights to this book," Robert Redford said to Robert Pirsig, author of Zen And The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.

"You've got them," Robert Pirsig replied. "I wouldn't have gotten this involved if I hadn't intended to give it to you." As a great review puts it: “Two famous guys talking in a famous city about making a famous book into a famous Hollywood movie.”

Robert Pirsig spends a whole chapter in his book, Lila, talking about the celebrity phenomenon. Why do we love to catapult people suddenly into celebrity, lavish praise and wealth upon them, and then, at the moment they at last become convinced of their worth, try to destroy them?

Pirsig claims that this is directly related to the classic Native American-European conflict of values. Quoting Pirsig:

“The root of the conflict is that you’re supposed to be socially superior like a European and socially equal like a Native American at the same time. It doesn’t matter that these goals are contradictory. So what you get is this tension, this business executives’ tension, where you’re the most relaxed, smiling, easy-going guy in the world—who is also absolutely killing himself to beat the competition and get ahead. Everybody wants their children to be valedictorians, but nobody is supposed to be better than anybody else. It’s bizarre. They love you for being what they want to be but they hate you for being what they’re not. There’s always this two-faced relationship with celebrity and you never know which face will appear next. The old Indians knew how to handle it. They just got rid of anything anybody wanted. They didn’t own property, they dressed in rags, some of them. They kept it down, laid low, and let the egalitarians and sycophants and assassins all look on them at worthless. That way they got a lot accomplished without all the celebrity grief.”

I was sad—but not surprised—to see the amount of hate that Lex got for sharing his reading list. I wouldn’t personally read those this year, but I think the drama that ensued is telling. This is a good video to understand what happened.

Nat Eliason also has a great writeup on a related topic: when did so many people start pretending Sapiens was bad?

I imagine you remember the mania as well as I do. After its launch in 2014, Sapiens gained a steady stream of accolades and support. By 2015 it was making its way onto seemingly every book list.

Naval Ravikant is the first person I remember hearing about it from, but then it was everywhere. Obama, Zuckerberg, Gates. It has been on the NYT Bestseller list for 182 weeks. It has over 68,000 Amazon reviews, a staggering number, especially for a nonfiction book.

For many people, it was among the first history books they enjoyed reading. It briefly introduced our evolutionary and societal history in a pop-nonfiction style that hadn’t been done particularly well in history before. Guns, Germs, and Steel would probably be the next-best book in this category, and its success seems to have only been a fifth of Sapiens.

Sapiens was the cool book to talk about, and almost no one was saying, “actually, it’s bad.” And I’m speaking about the casual social media reading crowd, not academics. There were some critiques from historians about its accuracy, sure, but people generally enjoyed the book.

At some point in the last couple of years, though, this changed. Sapiens has continued to sell well, but there’s a sort of sneering condescension about it, at least in some circles on Twitter. It has become cool to pretend that Sapiens is bad or lowbrow.

Nat covers a few reasons why this happened, but the last one is the most important:

But there’s a fourth reason some people are saying it’s bad that’s a bit sadder. They don’t recognize that they’re in this camp, of course, and they’ll tell themselves they’re in one of the other ones, but many people dunking on it fall into this group.

Jamie Ryan had a great thread on this phenomenon. Basically:

People are constantly vying for status

It’s much easier to seem high-status than to be high status

An easy way to seem high status is to criticize things that many people like, even if you liked it as well.

So a few people start criticizing something popular, and then it spreads because everyone else is afraid of being seen as a midwit who likes popular things. “If these people on Twitter are snickering at people who like Sapiens, then it must be mid, and I don’t wanna seem mid… mom said I’m special… I better pretend Sapiens is bad too.”

When a new cultural meme is rising, it’s high-status to talk about it because you’re ahead of the curve. You are a tastemaker who found it and liked it on its own merits. Not because of the hype.

But once a book, artist, movie, or whatever reaches a certain zenith of popularity, the status algebra flips. It’s now too popular for you to be seen recommending it. You’ll be seen as one of the masses. Not special. No gold star. So you must flip to saying, “Actually, it’s bad, IDIOT.”

And, look, sometimes mediocre work becomes popular for unknown reasons, like White Lotus. It’s a plodding show full of plot holes, and anyone who thinks the acting or soundtrack are good just hasn’t watched much quality television.

See how that felt? That was complete bullshit, White Lotus is fantastic, but if you thought White Lotus was good going into that sentence, now you’re worried you might be dumb. And now you need to go signal on Twitter how ~~artistic and cultured~~ you are by dunking on it.

So, yeah, don’t do that. If you like something, say you like it.

Don’t be swayed by the silly status monkeys.

Pair with: Status as a Service (StaaS)

This article describes a new type of startup that will emerge in 2023: the Silicon Valley small business.

What will it look like?

The Silicon Valley small business, the SV-SB, is a hybrid of sorts — it intertwines small business values and discipline with big tech know-how and ambition.

Founding teams may look like that of a “traditional” Silicon Valley startup. They’re native to Silicon Valley ethos, skills, and playbooks. But, beneath the surface, they’re different. You might see more solopreneurs and studios (and LLCs instead of C-corps). They value autonomy and flexibility. They envision a range of potentially good outcomes — not binary, all-or-nothing scenarios.

Teams stay small and run fast for as long as they can. I define a Silicon Valley small business as having 20 or fewer employees (and often less than 10). In my experience, startup teams above this size are forced to operate very differently — much slower, with more bureaucracy, and less alignment. But below the threshold, a savvy team can create leverage and punch above its size.

They’re growth-oriented and going for efficient scale. Unlike small businesses (and contrary to the common characterization of teams that bootstrap), SV-SBs aren’t just trying to build “lifestyle” businesses or modest passive income streams. They want to scale, as quickly and efficiently as possible. The desire and often the know-how to scale separates them from traditional small businesses, and their focus on doing it leaner and profitably can separate them from the traditional SV startup.

They try to bootstrap to profitability instead of relying on venture capital. They’re VC-literate yet aren’t charmed by the potential status, signal, or stability. Perhaps they raise the equivalent of a friends & family or pre-seed round but not much more. They look for capital-efficient businesses and prioritize profit alongside growth early on. With less money going in, there’s a lower bar for financial return. Moreover, “success” doesn’t require a billion dollar exit. Making millions is a win (and thousands keeps the team afloat).

It’s important that these archetypal attributes are deliberate operating choices, and not mere symptoms of a fleeting stage. Otherwise, it’s easy to look at every early-stage tech startup as a “Silicon Valley small business.”

An example of this is Gas.

The first part of the article explains a lot of what’s happening in society:

Many people believe we live in a “just world.”

The idea is that people generally think that the default is that the world is inherently fair. And believe unfairness is the result of mistakes or misconceptions or some kind of human error.

Which might help to explain the role of “compensatory self-enhancement.”

Researchers have found that when people learn that an individual is superior to themselves on some valued quality, their own self-esteem is thwarted.

People then respond by engaging in downward comparisons. They denigrate the threatening individual. After doing this, people report experiencing a boost in their mood.

For example, if someone sees a strikingly attractive person, they might say, “Well, that person is probably an airhead (I’m smarter than him/her).” Or if they see a rich person, they might say, “That person is probably immoral (I’m a better person than him/her).”

Similarity seems to play a role. People who feel threatened after learning someone similar to themselves is better on some quality feel especially good after engaging in downward comparison or denigrating them.

“That guy who is kind of similar to me might be more attractive but, I’ll bet he’s shallow. (There, now I feel better).”

Together, just world belief and compensatory self-enhancement imply that people resist the idea others could have a wide array of advantages and talents.

It just doesn’t seem fair that a rich guy might also be ethical, kind, good-looking, intelligent, and funny.

Money is so complicated. There’s a human element that can defy logic – it’s personal, it’s messy, it’s emotional.

Behavioral finance is now well documented. But most of the attention goes to how people invest. Welch’s story shows how much deeper the psychology of money can go. How you spend money can reveal an existential struggle of what you find valuable in life, who you want to spend time with, why you chose your career, and the kind of attention you want from other people.

There is a science to spending money – how to find a bargain, how to make a budget, things like that.

But there’s also an art to spending. A part that can’t be quantified and varies person to person.

In my book I called money “the greatest show on earth” because of its ability to reveal things about people’s character and values. How people invest their money tends to be hidden from view. But how they spend is far more visible, so what it shows about who you are can be even more insightful.

Everyone’s different, which is part of what makes this topic fascinating. There are no black-and-white rules.

But here are a few things I’ve noticed about the art of spending money.

1. Your family background and past experiences heavily influences your spending preferences.

For America’s new clerisy, scientific debate is a danger to be suppressed.

We live in an age when a high public health bureaucrat can, without irony, announce to the world that if you criticize him, you are not simply criticizing a man. You are criticizing “the science” itself. The irony in this idea of “science” as a set of sacred doctrines and beliefs is that the Age of Enlightenment, which gave us our modern definitions of scientific methodology, was a reaction against a religious clerisy that claimed for itself the sole ability to distinguish truth from untruth. The COVID-19 pandemic has apparently brought us full circle, with a public health clerisy having replaced the religious one as the singular source of unassailable truth.

The analogy goes further, unfortunately. The same priests of public health that have the authority to distinguish heresy from orthodoxy also cast out heretics, just like the medieval Catholic Church did. Top universities, like Stanford, where I have been both student and professor since 1986, are supposed to protect against such orthodoxies, creating a safe space for scientists to think and to test their ideas. Sadly, Stanford has failed in this crucial aspect of its mission, as I can attest from personal experience.

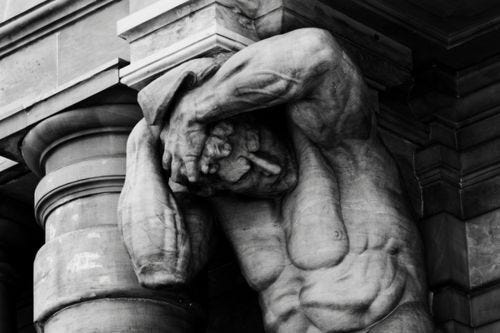

on reaching maximal potency

There’s that Charles Bukowski line from his poem Roll the Dice: If you’re going to try, go all the way. Otherwise, don’t even start. Most obsessive people crudely describe themselves as “all-or-nothing” types. They’ll say (read: I’ll say) that they are bad with moderation, that they need to “cut something out” if they want to cut back, which is just shorthand for “I only know how to go all the way.”

Bukowski goes on in his poem: Isolation is the gift. The rest is just a test of your endurance, of how much you really want to do it. This feels especially topical as I have begun to feel that pull of obsession to my writing. It’s like there is this constant, unrelenting tug at my psyche: get to the keyboard, get to the keyboard, you could be at the keyboard. And though I wish I could say the voice irritates me, in truth, I am on board with it. I find myself responding internally: I know! I am TRYING TO GET TO THE KEYBOARD.

We’re on the same team—me and my obsession. I’m consenting to it, letting myself fall into the quicksand. And it’s equal parts terrifying and thrilling. Thrilling because enjoying something so much that it’s all you want to be doing is such a privilege, right? And terrifying because isolation is, well, isolating. It’s great until it’s not. There’s that point where it starts to get dark, but it’s hard to anticipate when you’re reaching that point. Giving in to your obsession means surrendering most of the commonalities you have with the world around you. The overlap between you and everyone else begins to shrink. And the portion of your identity allocated to the obsession—to the work—grows.

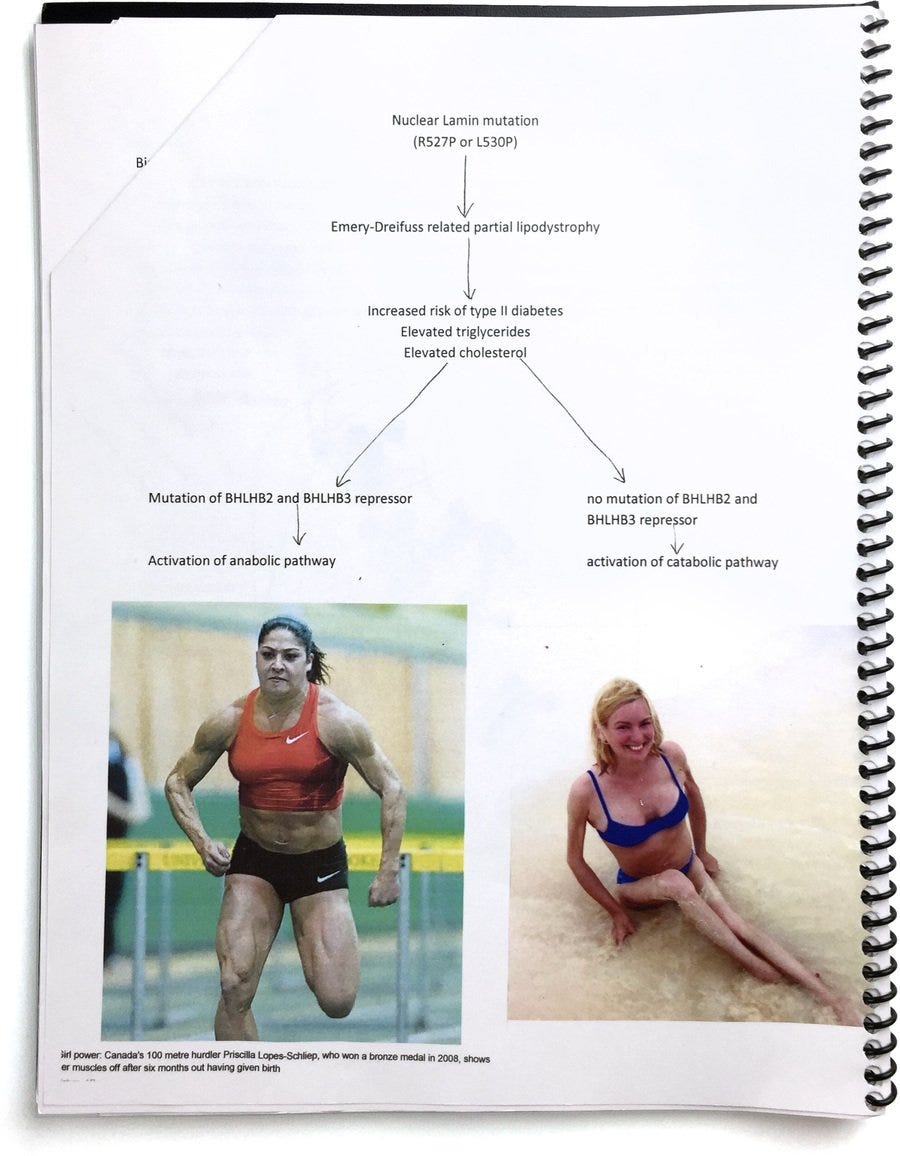

This fascinating article tells the story of how a woman whose muscles disappeared discovered she shared a disease with a muscle-bound Olympic medalist.

They were coming so quickly, and many were so unhinged, that I took a brief break from opening them.

And then I got one that had this subject heading: “Olympic medalist and muscular dystrophy patient with the same mutation.” Now that caught my attention. I wondered if it might point me to some article or paper in a genetics journal about an elite athlete I’d somehow missed.

Instead, it was a personal note from a 39-year-old Iowa mother named Jill Viles. She was the muscular dystrophy patient, and she had an elaborate theory linking the gene mutation that made her muscles wither to an Olympic sprinter named Priscilla Lopes-Schliep. She offered to send me more info if I was interested. Sure, I told her, send more.

A few days later, I got a package from Jill, and it was… how to put it?… quite a bit more elaborate than I had anticipated. It included a stack of family photos — the originals, not copies; a detailed medical history; scientific papers, and a 19-page, illustrated and bound packet. I flipped through the packet, and at first it seemed a little strange. Not ransom-note strange, but there were hand-drawn diagrams with cutouts of little cartoon weightlifters representing protein molecules. Jill had clearly put a lot of effort into this, so I felt like I had to at least read it. Within a few minutes, I was astounded. This woman knew some serious science. She off-handedly noted that certain hormones, like insulin, were too large to enter our cells directly; she referred to gene mutations by their specific DNA addresses, the way a scientist would.

And then I came to page 14.

There were two photos, side-by-side. One was of Jill, in a royal blue bikini, sitting at the beach. Her torso looks completely normal. But her arms are spindles. They almost couldn’t be skinnier, like the sticks jabbed into a snowman for arms. And her legs are so thin that her knee joint is as wide as her thigh. Those legs can’t possibly hold her, I thought.

The other picture was of Priscilla Lopes-Schliep. Priscilla is one of the best sprinters in Canadian history. At the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, she won the bronze medal in the 100-meter hurdles. It was the first Canadian Olympic medal in track and field since 1996. In 2010, Priscilla was the best 100-meter hurdler in the world.

The photo of her beside Jill is remarkable. Priscilla is in mid-stride. It’s difficult to describe just how muscular she looks. She’s like the vision of a superhero that a third-grader might draw. Oblong muscles are bursting from her thighs. Ropey veins snake along her biceps.

This is the woman Jill thought she shared a mutant gene with? I think I laughed looking at the pictures side-by-side. Somehow, from looking at pictures of Priscilla on the internet, Jill saw something that she recognized in her own, much-smaller body, and decided Priscilla shares her rare gene mutation. And since Priscilla doesn’t have muscular dystrophy, her body must have found some way “to go around it,” as Jill put it, and make enormous muscles.

If she was right, Jill thought, maybe scientists could study both of them and figure out how to help people with muscles like Jill have muscles a little more toward the Priscilla end of the human physique spectrum. Jill was sharing all this with me because she wasn’t sure how best to contact Priscilla, and hoped I would facilitate an introduction.

It seemed absolutely crazy. The idea that an Iowa housewife, equipped with the cutting-edge medical tool known as Google Images, would make a medical discovery about a pro athlete who sees doctors and athletic trainers as part of her job?

I consulted Harvard geneticist Robert C. Green to get his thoughts, in part because he has done important work on how people react to receiving information about their genes. Green was open to discussing it, but he recalls a justifiable concern that had nothing to do with science: “Empowering a relationship between these two women could end badly,” he says. “People go off the deep end when they are relating to celebrities they think they have a connection to.” I was skeptical too. Maybe she was a nutjob.

I had no idea yet that Jill, just by investigating her own family, had learned more about the manifestations of her disease than nearly anyone in the world, and that she could see things that no one else could.

Pair with: The Sports Gene: Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance

Pair with: Does Anyone Care About Men’s Struggles?

I wouldn’t say I dislike cooking, but in my day-to-day life, it’s just not my priority, and I’m totally fine eating almost the same things every day (chicken, meat, eggs, with rice or pasta and veggies/beans). I thought it was time to get a rice cooker to prepare good rice in a few minutes. Let me know if you have one you’d recommend.

I think people that multi-task pay a huge price. I think when you multi-task so much, you don't have time to think about anything deeply. You're giving the world an advantage you shouldn't do. Practically everybody is drifting into that mistake.

I did not succeed in life by intelligence. I succeeded because I have a long attention span.

— Charlie Munger

Thanks for reading!

If you like The Long Game, please share it on social media or forward this email to someone who might enjoy it. You can also “like” this newsletter by clicking the ❤️ just below, which helps me get visibility on Substack.

Until next week,

Mehdi Yacoubi