Getting a job as an engineering executive. @ Irrational Exuberance

Hi folks,

This is the weekly digest for my blog, Irrational Exuberance. Reach out with thoughts on Twitter at @lethain, or reply to this email.

Posts from this week:

-

Getting a job as an engineering executive.

-

Make an effective executive LinkedIn profile.

-

How to capitalize engineering costs.

-

Trying Tailscale.

Getting a job as an engineering executive.

I started my first executive job search when I was 25. Eventually, I got an offer to lead engineering at a startup with four engineers, which I turned down to join Uber. It wasn’t until a decade later that I joined Calm and started my first executive role. If you start researching executive career paths, you’ll find folks who nominally become engineering executives at 21 when they found a company, and others that are 30+ years into their career without taking an engineering executive role.

As these anecdotes suggest, there is no “one way” to get an engineering executive job. However, the more stories you hear about finding executive roles, the more they start to sound pretty similar. If you’re looking to find an executive role, I’ve condensed the many stories I’ve heard, along with my own experiences, into the repeatable process that prospective candidates typically follow.

To be explicit, I am defining “engineering executive” here as “the functional leadership role responsible for all of engineering at a given company.” This is title independent because companies use titles in inconsistent ways. Sometimes companies will extend titles like CTO, VP of Engineering, or Head of Engineering to someone managing a fraction of engineering. Other times you’ll find a VP of Engineering reporting to a CTO, but where the VP is performing all functional leadership duties. You will also find companies that describe all 200 of their Engineering Directors as executives. That’s fine, just not how the term is being used here!

Why pursue an executive role?

If you’re spinning up your first executive role search, you should have a clear answer to a question you’ll get a number of times, “Why are you looking for an executive role?” It’s important to answer this for yourself, as it will be a valuable guide throughout your search. If you’re not sure what the answer is, spend time thinking this through until you have a clear answer (maybe in the context of a career checkup.

Once you’ve written your rationale down, review it with a few peers or mentors who have already been in executive roles. Incorporate their feedback, and you’re done.

The other side of this is that interviewers are also very curious about your reason for pursuing an executive role, but not necessarily for the reason you’d expect. Rather than looking for your unique story (although, yes, they’ll certainly love a memorable, unique story), they’re trying to filter out candidates with red flags: ego, jealously, excessive status-orientation, and ambivalence.

1 of 1

Limited release luxury items (e.g. fancy cars) sometimes label each item with their specific production number along with the size of the overall run. For example, you might get the fifth car in a run of twenty cars overall. The most exclusive possible production run is “one of one.” That item is truly bespoke, custom, and one of a kind.

All executive roles and processes are “one of one.”

For non-executive roles, good interviewing processes are systematized, consistent, and structured. Sometimes the interview process for executive roles are well-structured, but they often aren’t. If you approach these bespoke processes like your previous experiences interviewing, your instincts may mislead you through the process.

The most important thing to remember when searching for an executive role is that while there are guidelines, there are stories, there are even statistics, there are no rules when it comes to finding executive jobs. There is a selection bias in executive hiring for confidence, which makes it relatively easy to find an executive who will tell you with complete confidence how things work, but be a bit wary. “One of one” means that anything is possible, in both the best and worst possible sense.

Finding internal executive roles

Relatively few folks find their first executive job through an internal promotion. These are rare for a few reasons, the first is that each company only has one engineering executive, and that role is usually already filled. The second is that companies seeking a new engineering executive generally need someone with a significantly different set of skills than the team they already have in place.

Even in cases where folks do take on an executive role at their current company, they often struggle to succeed. Their challenges mirror those of taking on tech-lead manager roles, where they are stuck both learning how to do their new job in addition to performing their previous role. They are often also dealing with other internal candidates who were previously their peers and may feel slighted by not getting the role themselves. This makes their new job even more challenging, and can also lead to departures hollowing out the organization’s key leaders at a particularly challenging time.

That’s not to say that you should avoid or decline an internal promotion into an executive engineering role, just that you should go into it with your eyes open. In many ways, it’s harder to transition internally than externally. Even if you have a rough experience, you may well be wholly qualified to join another company externally.

Finding external executive roles

Most executive roles are never posted on the company’s jobs page. So before discussing how you should approach your executive job search, let’s dig into how companies usually find candidates for their executive roles. Let’s imagine that my defunct company, Monocle Studios, had been a wild success and we wanted to hire our first CTO.

How would we find candidates? Something along the lines of:

- Consider any internal candidates for the role

- Reach out to the best folks in my existing network, seeing if any are interested in interviewing for the role

- Ask our internal executive recruiter to source candidates; I’d skip this step if we didn’t have any executive recruiters internally, as generally there’s a different network and approach to running an executive search than a non-executive search

- Reach out to our existing investors for their help, relying on both their networks and their firms’ recruiting teams

- Hire an executive recruiting firm to take over the search

Certainly not every company does every job search this way, but it does seem to be the consistent norm. This structure exposes why it’s difficult to answer the question, “How do I find my first executive role?” The quick answer is to connect with an executive recruiter, but that approach comes with some implications on the sort of roles you’ll get exposed to. Typically these will be roles that have been challenging to fill for some reason. The most desirable roles, and roles being hired by a well-networked and well-respected CEO, will never reach an executive recruiting firm.

This is, by the way, absolutely not a recommendation against using executive recruiters. Executive recruiting firms are fantastic. A good executive recruiter will coach you through the process much more diligently than the typical company or VC in-house recruiter. I found my first executive role through an executive recruiter, as did the majority of my peers, simply a perspective to keep in mind. Similarly, it’s not true that all founder-led searches are for desirable jobs–almost all executive roles start as founder-led searches before working their way through the pipeline.

Looking at the pipeline, there are many ways to increase your odds of getting executive opportunities at each step. The basics still matter: maintain an updated LinkedIn profile, respond politely to recruiters who do reach out. Both have a surprising way of creating job search serendipity, and make sure your network is aware that you’re looking. If you don’t personally know many recruiters at investors or executive recruiters, your network can be particularly helpful at those introductions.

There are also a small number of companies that do post executive roles publicly, and there’s certainly no harm in looking through those as well. The one challenge is that you’ll have to figure out whether it’s posted publicly because the company is very principled about searching for talent outside their personal networks (often a good sign), or if the role has already passed unsuccessfully through the entire funnel described above (often not a good sign).

Finally, if you’re laying the groundwork for an executive search a few years down the road, there’s quite a bit you can do to prepare. You can join a large or high-growth company to expand your network, work in a role where you get exposure to the company’s investors, create more visibility of your work to make it more likely for founders to reach out to you, or get more relevant experience growing and operating an engineering organization.

Interview process

The interview process for executive roles is always a bit chaotic. The most surprising thing for most candidates is that the process often feels less focused or effective than their other recent interviews. This is because your hiring manager as a Director of Engineering is usually an experienced engineering leader, but your hiring manager as an engineering executive is usually someone with no engineering experience at all. In the first case, you’re being interviewed by someone who understands your job quite well, and in the latter the interviewer usually has never worked in the role.

There are, inevitably, exceptions! Sometimes your interviewer was an engineering executive themselves at an earlier point in their career, but that usually isn’t the case. The most common scenario is when a technical founder interviews you for the role, potentially with them staying as the CTO and you taking on the VPE title, but even then it’s worth noting that the title is a bit of a smokescreen, and they likely have limited experience as an engineering executive.

Consequently, engineering executive interviews depend more heavily on perceived fit, prestige, the size of the teams you’ve previously managed, being personable, and navigating the specific, concrete concerns of would-be direct reports and peers. This makes the “little things” particularly important in executive interviews: send quick, polite follow-ups, use something like the STAR method to keep your answers concise and organized, prepare questions that show you’re strengthening your mental model of how the company works, and generally show energy and excitement.

The general interview process that I’ve seen is along the lines of:

-

Call with a recruiter to validate you meet the minimum requirements, are a decent communicator, and won’t embarrass them if you talk to the CEO. Also a good opportunity for you to understand whether there are obvious issues that might make this a bad role for you (wrong job location, wrong travel expectations, etc)

-

Call with the CEO or another executive to assess interest in the role, and very high-level potential fit for the role. You’ll be evaluated primarily on your background, your preparation for the discussion, the quality of your communication, and perceived excitement for the company.

Coming to this interview having researched the opportunity, and showing excitement for the company, is your biggest leverage point to influence the hiring process

-

Series of CEO or founder discussions where you dig into the business, and their priorities for the role. This will be a mix of you learning from them, them learning about you, and getting a sense of whether you’ll work together well. The exact structure will vary depending on the CEO, and give you an understanding of what kind of person they are to work with

-

One-on-one discussions with a wide smattering of peer executives and members of the team that you would manage. These vary widely across companies, and it is surprisingly common for the interviews to be poorly coordinated, having e.g. the same topics come up multiple times across different interviewers.

This is somewhat frustrating. Generally it means the company is missing someone with the right position, experience and energy to invest into designing the loop, so it ends up being rather chaotic. I’ve had these interviews turn into general chats, programming screens, architecture interviews, and anything else you can imagine. All I can say is: roll with it to the best of your ability

-

Presentation interview to executive team, your directors, or a mix of both. Usually you’ll be asked to run a sixty minute presentation describing your background, a point of view on what’s important for the business moving forward, your understanding of what you would focus on in the new role if hired, and your plan for your first ninety days.

A few tips that I’ve found effective for these interviews: ask for feedback on your presentation before the session, make sure to follow the prompt directly, prioritize where you want to spend time in the presentation on the highest impact topics, and make sure to leave time for questions (while also having enough bonus content to fill the time if there aren’t many)

If this sounds surprisingly vague and a bit random, then yes, you’ve read it correctly. Gone are the days of cramming all the right answers. Now it’s a matter of reading each individual effectively, and pairing the right response to their perspective.

Negotiating the contract

Once a company decides to make you an offer, you enter into the negotiation phase. While the general rules of negotiation still apply–particularly don’t start negotiating until the company knows it wants to hire you–this is a moment when it’s particularly important that these are 1 of 1 jobs. Compensation consultants and investors will have recommended compensation ranges, but each company only hires one engineering executive at a time, and every company is unique.

Fair compensation will vary greatly depending on the company, the size of its business, your location, and your own background. Your best bet will be reaching out to peers in similar roles to understand their compensation. I’ve found folks to be surprisingly willing to share compensation details. It’s also helpful to read DEF 14 filings for public companies, which explain their top executives’ base, bonus and equity compensation (for example, here is Splunk’s DEF 14A from 2022).

There are a few aspects of this negotiation that are sufficiently different from earlier compensation negotiations that they’re worth mentioning:

-

Equity is issued in many formats: stock options, Restricted Stock Units, and so on. They are also issued with many conditions: vesting periods (often 4 years), vesting cliffs before vesting accrues (often 1 year), and the duration of the period after you depart when you’re able to exercise options before they expire (often 90 days).

Most of these terms are negotiable in an executive offer, but it all comes down to the particular company you’re speaking with. You may be able to negotiate away your vesting cliff, and immediately start vesting monthly rather than waiting a year. You may be able to negotiate an extended post-departure exercise window, even if that isn’t an option more widely. You may be able to have the company issue you a loan to cover your exercise costs, which combined with early exercise might allow you to exercise for “free” except for the very real tax consequences.

To determine your negotiation strategy, I highly recommend consulting with a tax advisor, as the “best” option will depend on your particular circumstances

-

Equity acceleration is another negotiation point around equity, that’s worth calling out as it’s common in executive offers, and extremely uncommon in other cases. Acceleration allows you to vest equity immediately if certain conditions are met. Many consider this a standard condition for a startup contract, although there are many executives who don’t have an acceleration clause.

One topic that gets perhaps undue attention is the distinction between single and double trigger acceleration. “Single trigger” acceleration has only one condition to be met (for example, your company is acquired), whereas “double trigger” acceleration will specify two conditions (for example, your company is acquired and you lose your job). My sense is that people like to talk about single and double triggers because it makes them sound knowledgable about the topic rather than it being a particularly nuanced aspect of the discussion.

-

Severance packages can be negotiated, guaranteeing compensation after you exit the role. There is little consistency on this topic. Agreements range from executives at very small companies that’ve pre-negotiated a few months salary as a severance package, to executives leaving highly compensated roles that require their new company to make them whole on the compensation they’re leaving behind. There are also many executive contracts that don’t pre-negotiate severance at all, leaving the negotiation until the departure (when you admittedly have limited leverage to work with)

-

Bonus size and calculation can be negotiated. On average, bonus tends to be a larger component of roles outside of engineering, such as a sales executive, but like everything, this is company and size specific. A CTO at a public company might have their bonus be equal in size to their salary. A CTO at a Series C company might have a 20% bonus. A CTO at a 50 person company might have no bonus at all.

In addition to the size of your bonus, you may be able to negotiate the conditions for earning it. This won’t matter with companies that rely on a shared bonus goal for all executives (sometimes excluding sales), but may matter a great deal at others that employ bespoke, per-executive goals instead

-

Parental leave can be negotiated. For example, some companies might only offer paid parental leave after a year of service, but you can absolutely negotiate to include that after a shorter amount of service. (It’s worth noting, this is often negotiable in less senior roles as well.)

-

Start date is generally quite easy to negotiate in less senior roles, but can be unexpectedly messy for executive roles. The reason it gets messy is that the hiring company often has an urgent need for the role to be filled, while also wanting to see a great deal of excitement from the candidate about joining.

The quiet part is that many recruiters and companies have seen executive candidates accept but later not join due to an opposing offer being sweetened, which makes them uncomfortable delaying, particularly for candidates who have been negotiating with other companies, including their current one

-

Support to perform your role successfully. The typical example of vain requests for support are guaranteed business or first-class seats on business travel, but there are other dimensions of support that will genuinely impact your ability to perform your role. For example, an executive assistant can free up hours every week for focus work, and sufficient budget to staff your team can easily be the difference between a great and terrible first year.

The negotiation phase is the right time to ask for whatever you’ll need to succeed in the role. You’ll never have an easier time to ensure you and your organization can succeed

Negotiate knowing that anything is possible, but remember that you have to work with the people you’re negotiating with after the negotiation ends. If you push too many times, you won’t be the first candidate to have their offer pulled because the offering company has lost confidence that you really want to be there.

Deciding to take the job

Once you get an offer for an executive position, it can be remarkably hard to say no. The recruiters you’re working with will push you to accept. The company you’re speaking with will push you to accept. You’ll have invested a great deal of work into the process as well, and that will bias you towards wanting to accept as well.

It’s also challenging to evaluate an executive offer, because ultimately you’re doing two very difficult things. First, you’re trying to predict the company’s future trajectory, which is hard even for venture capitalists who do it a lot (and they’re solving for an easier problem as they get to make many concurrent investments, you can only have one job at a time). Second, you’re trying to make a decision that balances all of your needs, which a surprising number of folks get wrong (including taking prestigious or high-paying jobs that they know they’re going to hate, but just can’t say no to).

I can’t really tell you whether to accept your offer, but there are a few steps that I would push you to conduct before finalizing your decision:

-

Spend enough time with the CEO to be sure you’ll enjoy working with them, and trust them to lead the company. While it changes a bit as companies scale, and particularly as they go public, the CEO is the person who will be deciding company direction, determining the members of the executive team, and responsible to resolve the trickiest decisions

-

Speak to at least one member of their board. Admittedly, board members won’t directly tell you anything too spicy, but their willingness to meet with you is an important signal, and it’s the best opportunity to start building your relationship with the board

-

Make sure you’ve spoken with every member of the executive team that you’d work with regularly. Sometimes you’ll miss someone in your process due to scheduling issues, and it’s important to chat with everyone and make sure they’re folks you can build an effective working relationship with

-

Have someone on the finance team to walk you through the company’s most recent profit and loss statement. You will need to sign a Non Disclosure Agreement, but it would be a very odd sign if a company was unwilling to share this information with you

-

Make sure they’ve actually answered your questions. I once interviewed to be a company’s head of engineering, where they refused to share their current valuation with me! I pushed a few times, but ultimately they told me it was unreasonable to ask, and I decided I couldn’t move forward with a company that wouldn’t even share their valuation with an executive candidate.

Don’t assume they’ll tell you after you join if they won’t tell you when trying to convince you to accept their offer. You will never have more leverage to get questions answered than in the hiring process: if it’s important and they won’t answer, be willing to walk away

-

If the company has recently had executives depart, see if you can get an understanding for why. This could be mutual friends with the departed executive, or even chatting with them directly

As you work through those steps and are you still excited? Have you explained your thinking about the role to at least two friends, and they didn’t raise any serious concerns? Then, generally speaking, take the job!

Not getting the job

Finally, you can’t talk about running an engineering executive search without talking about not getting the job. Who doesn’t have a story of getting reached out to by a recruiter, who then ghosts them after an initial screen? A public company recently invited a friend of mine to interview in their CTO search, got my friend very excited, and then notified them the next week that they had already tentatively filled the role. I’ve had first discussions with CEOs where we both immediately know we won’t be a good fit to work together.

Although rejection isn’t fun, the perspective that I find helpful is that your search’s goal is not finding an executive job, but rather finding an executive job where you will thrive. It’s much better to realize a job isn’t the right fit for you before taking it, and each opportunity that doesn’t move forward is for the best.

As an aside, I find Phyl Terry’s Never Search Alone a helpful book when thinking about executive job searches.

Make an effective executive LinkedIn profile.

tl;dr - it’s valuable to update your LinkedIn profile to be a concise, accurate, and current summary of your accomplishment. Spend at most two hours updating it, then ask a friend (ideally a recruiter) for feedback. Incorporate that feedback and don’t think about your profile again for at least a year.

While writing my notes on landing an engineering executive role, a topic that came up in feedback a number of times was how valuable it is to have a reasonably good LinkedIn profile. There’s absolutely diminishing returns in going from decent to fantastic, but it’s well worth investing several hours into your profile unless you’re confident you can find the roles you’re interested in from investors, CEOs, or recruiters who you already have a working relationship with.

I’ll start with some general commentary on whether LinkedIn profiles matter, give advice on setting up your LinkedIn profile, and end explaining the choices I’ve made in putting my LinkedIn profile together.

When does your LinkedIn profile matter?

Your LinkedIn profile won’t help with an internal job search or if you have deep, existing relationships with CEOs, investors and recruiters. Conversely, if you’re relying on inbound recruiter interest or hope to work with an executive recruiting firm, then your LinkedIn profile will be important.

Even if it’s not worth updating your LinkedIn profile to increase your visibility for interesting roles, it’s still worth updating it to make you a more effective hiring manager. To a significant degree, candidates’ first evaluation of you, and your company, will anchor on their experience of reading your LinkedIn profile and activity.

Why reasonably good is your goal

Your LinkedIn profile is your resume for many job hunts these days. In job searches, most folks will see your LinkedIn profile, whereas relatively few will see your resume. That said, almost none of them will spend more than two minutes looking at it.

Because few folks spend much time on it, formatting only matters so much, and too much content can easily work against you by crowding out the most valuable pieces. Your accomplishments matter significantly more than your formatting. Spend at most two hours improving your LinkedIn profile, then return your focus to doing things valuable enough to one day add to that profile.

Goals

Your goals for your LinkedIn profile are:

- Accurate and recent summary of your accomplishments

- Highlight your various sources of prestige

- Brief enough to skim in two minutes

- Breadcrumbs to learn more about you and your accomplishments

- Avoid introducing any red flags

That’s it! If you try to do more than that, you will crowd out more valuable pieces with something less valuable. Adding a few pieces of more concrete advice here:

-

Do not spend more than two hours working on your LinkedIn profile. Take some time to improve it, save the improvements, and come back to it in a year. There is really only so much you can do, and spending more time won’t make it much better

-

If you’re not sure, ask a recruiter–with relevant recruiting experience!–for their feedback. The recruiter is always right, just take their advice. If you don’t know any recruiters with relevant experience, you can also ask a non-recruiting executive for their feedback

-

Before editing your profile, search for ten executive profiles, and take notes on what does or doesn’t resonate to you, from the perspective of a recruiter or hiring manager. Your goal isn’t to stand out, rather it’s to “fit in” with those profiles

-

The profile that you see is not necessarily the profile that others see. Start by understanding what others see so you can prioritize your time in those areas. In a job search, many viewers will see your public or PDF versions, which is very pared down. Logged-in users (other than yourself) will see something of a hybrid between the public version and what you see.

Exactly how to see the public version moves around periodically, but the easiest is to download the PDF version (currently from your profile page, go to “More” then “Save to PDF”), although there’s usually a way to see your public profile (currently from your profile page, go to “Edit public profile & URL”). There’s no convenient way to see exactly what other logged-in users see, the best case is to just ask a friend to screenshot it for you

-

Summarize rather than aim to be exhaustive. The worst profiles are empty, but the second worst have so much content that you’re not sure where to look. If it takes more than two minutes to skim, you have too much stuff.

You should summarize both in the roles you include on your profile, and also in each role’s description. If you go beyond two paragraph, you can be confident that no one will read it, so instead edit down to what’s most important.

The desire to be exhaustive is a very frequent error in aspiring executive leaders’ profiles, often making them hard to read. Does it really matter that you’re an angel investor or advisor in a given company? It might, if it’s a very prestigious company, but it probably doesn’t, and it’s definitely distracting. Worse, it may also give the impression that you’re not focused on your core work

-

A clear description is particularly important for ambiguous roles, e.g. “Head of X” is much less clear than “VP Engineering”, which is slightly less clear than CTO. It’s very important to explain the scope of your role if it isn’t clear from the title. For example, “Reporting to CEO, leading the full engineering organization.” would reassure recruiters that your “Head of Engineering” role is what they’re looking for.

You might say, “Head of Engineering is a very clear title.” and unfortunately you would be wrong. There are well-known companies with dozens of “Head of Engineerings” roles, some of which are roughly equivalent to another company’s senior engineering manager role

-

Your profile should capture your top sources of prestige: companies you worked at, particularly popular blog posts, conference talks, college, published work, and so on. Again: think summary rather than comprehensive

-

Maintain a small personal website on a domain you control (I’d recommend Hugo and Github Pages), and link out to that from your profile. This makes it possible for interested readers to learn more without including all that content in your profile itself

-

Don’t worry about keyword stuffing (aka adding relevant search terms) at all. There is some debate on whether this matters for any resumes, but it’s very low impact for executive positions. Generally executive candidates are discovered through their current company (“what are the top 50 developer experience startups? Who are the engineering executives there?”), conference speaking (“what is the complete list of speakers at this engineering conference, are any of them interesting prospects?”), or something similar

-

Finally, try to work around any red flags in your experience. If you’re not sure what your red flags might be, put on your hiring manager hat, or again pull in an executive or recruiter to borrow their eyes.

One example issue is a string of short stints. For example, an executive who has spent less than a year in their last two roles might scare off potential roles. You might be able to–in good faith–combine two of those stints into one stint if it was due to an acquisition, as you have been effectively in one role throughout. When a recruiter is skimming resumes for short stints, they are trying to filter out perceived “job hopping”, and combining these roles would avoid that potential confusion.

You can reasonably argue that many of these red flags are not fair. That is true. We’re trying to make an effective LinkedIn profile, solving fairness is well outside our current scope

There are certainly more things you could do, but that should take you well through your two hours of budgeted time.

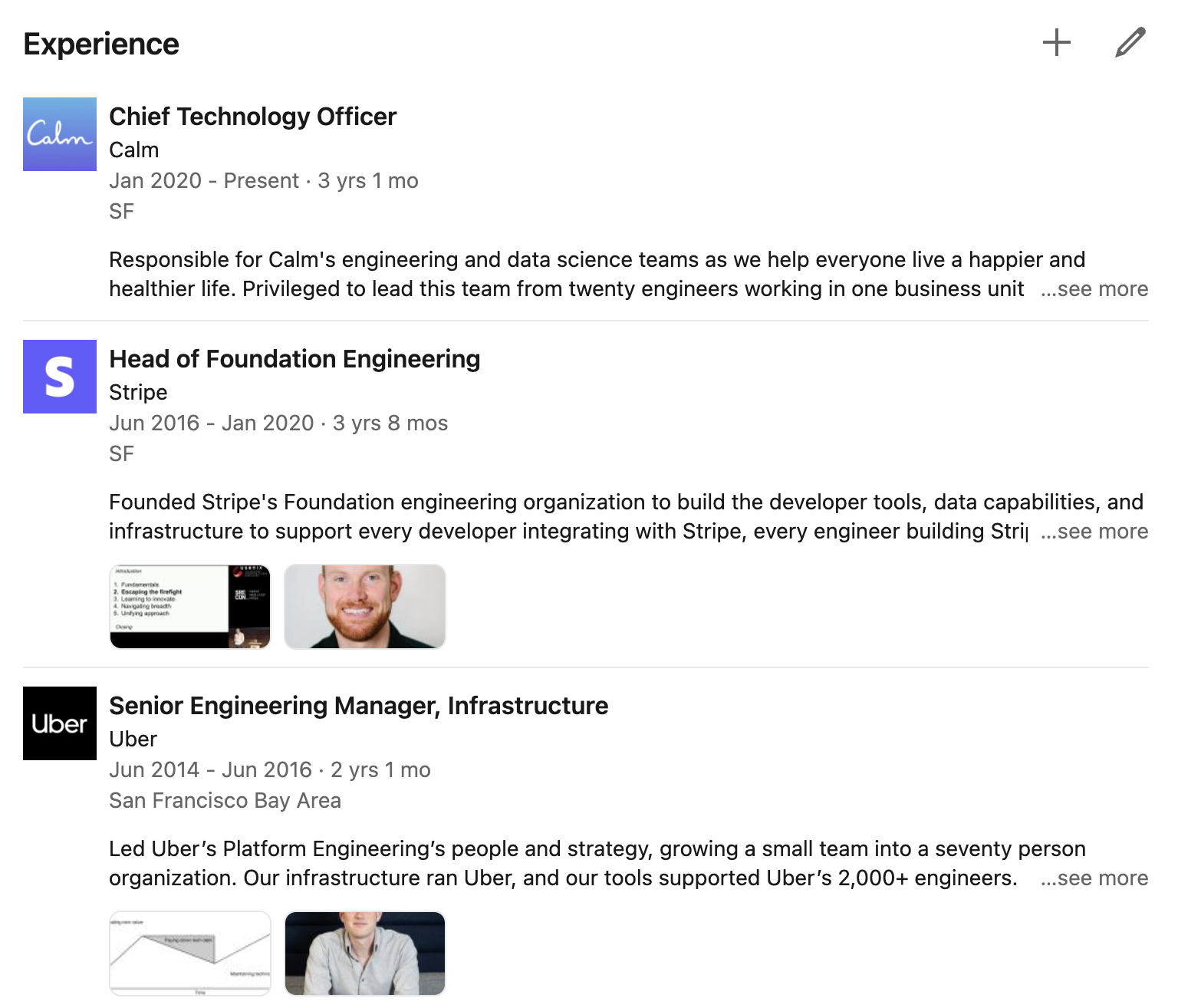

Breaking down my LinkedIn profile

So I’ve written down some abstract rules above, but I thought it might be useful to concretely walk through my LinkedIn profile and explain the various choices I’ve made. This is just my profile, there are certainly much better ones out there, but it’s the easiest one for me to specifically discuss.

I’ll walk through the contents of the public profile first, then discuss a few other aspects that are not shown in the public profile, but are visible for any logged-in LinkedIn member. The first thing to discuss briefly is my profile’s URL: https://www.linkedin.com/in/will-larson-a44b543/

It’s not a particularly clean URL, I’d certainly recommend starting with a more concise one. That said, I haven’t seen any evidence that having a shorter profile URL really matters. These links are being copy-pasted around after being discovered through LinkedIn search, no one is typing your LinkedIn URL from memory. Instead, I’ve optimized for a durable URL that has remained the same rather than tweaking it to be shorter.

The top section of the profile has four important pieces: headline, profile image, background image, and the about section. My general philosophy for these sections is to be very concise and eliminate any extraneous information.

My headline is my current title at my current role: Chief Technology Officer at Calm. My informal research is that the more senior the individual, the less likely they are to include additional information in their headline (angel investor, coach, mentor, etc) or refer to their previous employers (ex-Stripe, ex-Google, etc). That said, as best I can tell, it really doesn’t matter much either way.

For the profile and background images, I personally think it’s worthwhile to have professional photography of some sort. For the profile picture, that means getting professional photos made at some point and reusing them indefinitely. For the background image, there’s likely an asset from your company that you can reuse. That said, does it really matter? No, I don’t think it does. There are folks getting reachouts with neither a profile or background image.

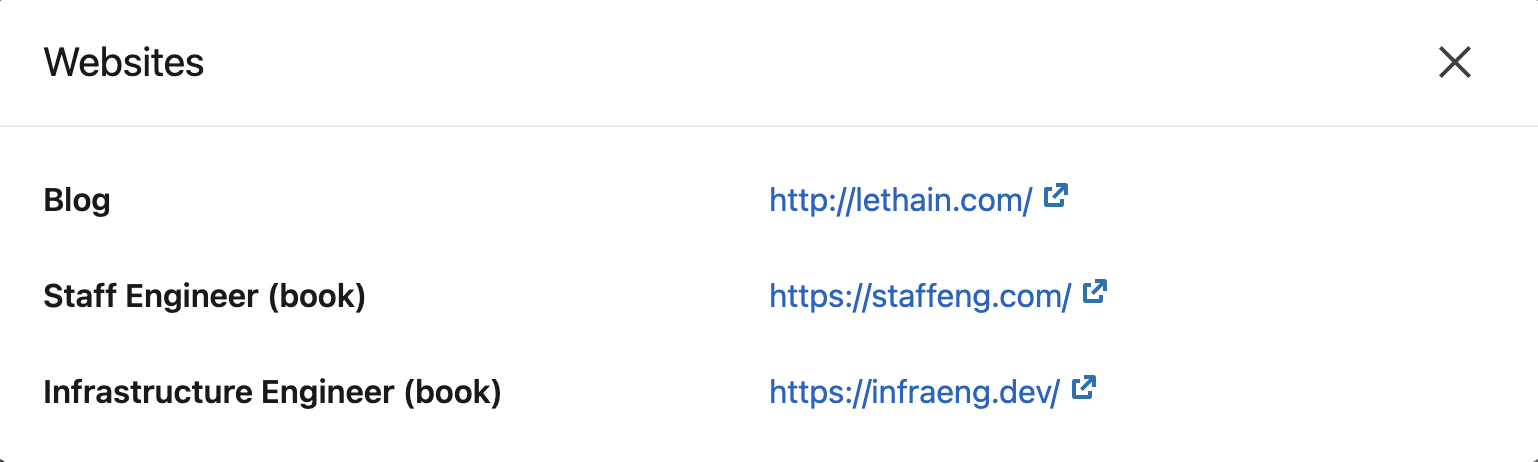

Finally, there is also the “websites” link which pops up links to your websites.

I personally think it’s worthwhile for every executive to maintain a website of some sort,

even if it’s just a collection of profile links and an email address to reach you.

For a long time, the only link I included here was to lethain.com, but over time I’ve added

two other writing projects as well.

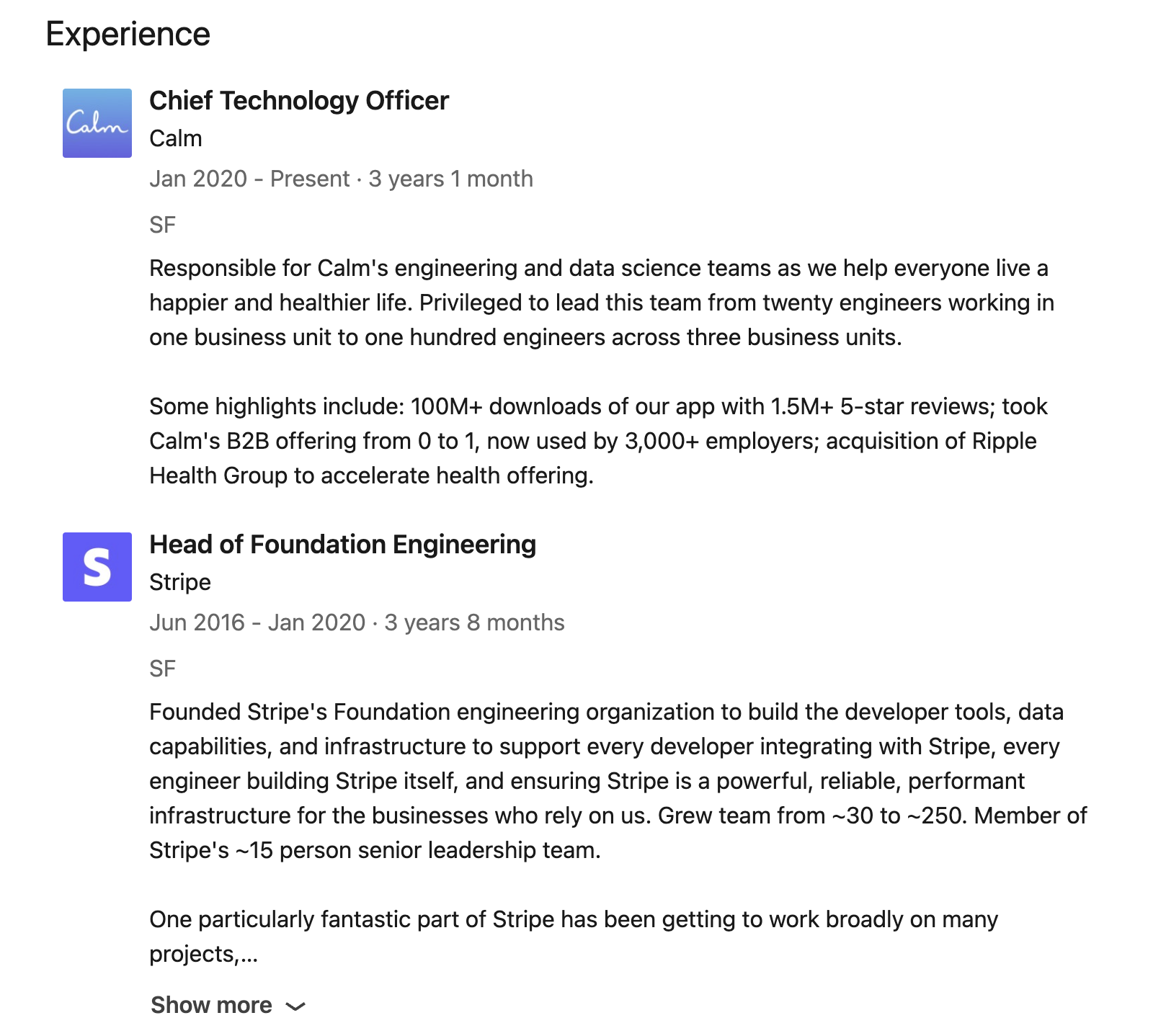

Next, you can see the descriptions of my work at Calm and Stripe. These are my two most recent roles, so I’ve dedicated a bit more space to describing my work, although in both cases I only use two paragraphs. (I’ll note that the more senior the individual, usually the less they write about their work, unless someone else has written their LinkedIn profile for them. Part of the unstated dynamic here is figuring out “how senior” you want to be percieved, and editing down to that threshold, without omitting context necessary to justify your seniority.)

For every role, I tried to do two things: explain what the role actually was to avoid confusion (especially for ambiguous roles like “Head of Foundation Engineering” at Stripe, which is a bit open ended), and include numerical accomplishments describing the role. Finally, it’s somewhat declasse to anchor on headcount as an accomplishment, but I find that most executive recruiters filter candidates based on previously managed headcount, so I consider it valuable to include.

Historically, I was anxious about my resume showing a series of two-year stints, and wanted to emphasize that my time at Digg was really a four-year stint, split by being acquired. To message that more directly, I decided to combine my time at Digg and SocialCode into a single segment. To avoid confusion, I was very deliberate about the acquisition in both the post-acquisition role’s title and description.

For my oldest roles, I’ve compacted their description down to a sentence. If there is something particularly unique in your previous experience, absolutely mention it, but otherwise folks are generally not that concerned with the details of work you did eight-plus years ago. (I actually forgot this, but I also removed my older, non-engineering roles entirely. They’re just not relevant to my current professional goals.)

The last section of the public profile is the list of publications. I’ve used this to highlight my two books. At one point, I also included individual pieces I’d published, like this one in Increment, but I pruned down over time. Generally speaking, the publications section is not important for most executive jobs (as opposed to e.g. a research role), and don’t feel nervous about leaving it blank.

Alright, that’s all the sections of the public profile (including the PDF version, which is more-or-less a PDF formatted version of the public profile). There is just one more thing worth mentioning in the logged-in version, which is adding media for your jobs.

When someone reads your resume, you want them to get excited about the idea of working with you, and watching a video of you speaking about a relevant topic is very likely to get them excited. Wherever possible, I include relevant video of me speaking about work done at a given company.

While I believe videos build the most visceral connection, other mediums of content (e.g. blog posts) can also be effective. LinkedIn does a good job of packing the media into a small amount of space, so it’s an easy opportunity to allow folks to learn more about your work without overwhelming the page. Remember, of course, that most folks won’t watch or read what you’ve linked, but it’s there for those who are most interested.

Finally, two ending thoughts. First, there’s obviously no “right” way to make a LinkedIn profile, particularly not for executives. Do what makes sense to you, get feedback from experienced recruiters, and cap your time investment at a few hours. Second, a good profile will never drive people to read it; instead you need to do something notable or write something interesting.

How to capitalize engineering costs.

There are many important meetings in your first ninety days as a new engineering leader, but one that’s both easy to forget and surprisingly important is your first meeting with the finance team. There’s a lot to learn from the finance team, particularly drilling into your profit and loss statement, but there’s one narrow topic that causes a surprising amount of frustration between engineering and finance teams: how do you capitalize software engineering costs?

Capitalizing software costs is a financial concern, not an engineering one, driven by the finance team’s obligations to follow the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Generally, the finance team’s auditors won’t certify their annual financial audits unless they’ve followed GAAP, part of which is deciding whether to capitalize or expense each incurred cost. Capitalizing costs is generally preferable, as it allows them to be amortized over time, showing a higher net income. That said, most finance teams are much more focused on GAAP compliance than on maximizing capitalization. (Exceptions do exist, particularly as the relative size of engineering spend increases.)

The general guidance on capitalizing software engineering costs is straightforward: development of new software capabilities should be capitalized, and everything else should be expensed. In practice, there’s a great deal of flexibility in deciding what is or isn’t a new capability. This is the same challenge as agreeing on whether a given task is really a new feature and bug fix: most changes can be reasonably argued either way.

A surprising number of engineering capitalization discussions don’t start with a clear articulation of what each side needs, which makes it very challenging to agree on a good approach. My experience is that there are only three core criteria to address to keep everyone involved happy:

- Easy to explain and justify to an auditor

- Available in a timely manner for finance’s financial reporting

- Minimizes both finance and engineering team’s ongoing efforts

Before deciding on your approach to capitalization, make sure both engineering and finance agree on their needs! Going further without agreement is madness, and will always end with a political solution rather than a reasoned one.

Capitalization approaches

Although you can solve this problem in many different ways, most organizations end up going with one of four approaches:

- Ticket-based: track capitalization status and time for each ticket. Establish a default for tickets without a capitalization status (likely that it will be expensed), and then sum hours of capitalizable work across tickets for each engineer, multiplied by hourly cost, to determine capitalizable engineering costs

- Project-based: track hours for each project, and determine a capitalization weighting for each project (80% capitalized, 0% capitalized, etc) based on the nature of the work. Finance then combines this with a synthetic hourly engineering cost based on average team or organization hourly rate

- Role-based: set a fixed percentage of time for each role. For example, 80% of product engineer time should be capitalized, 0% of infrastructure engineering time should be capitalized, etc

- Vendor-specific: There are also a number of vendors, including Jellyfish, that provide methodologies for capitalization

Most companies rely on either ticket or project-based approaches. Engineering teams tend to prefer the role-based model, but many finance teams and auditors will view this approach with skepticism, so it’s less common than you might imagine, although some companies do indeed practice it. That said, it is common to see a hybrid ticket or project plus role based approach: relying on tickets to track capitalizable work on product engineering teams but assuming other engineering teams have no capitalizable work.

Finally, there are many vendors that want to help you with this problem. Each should be evaluated according to the three core criteria discussed above, particularly ensuring that your auditor would be comfortable with the methodology, along with their pricing.

There is no perfectly clean solution here, although hopefully you can now have a more fruitful discussion with your finance team about the options. I’m still annoyed by the overall inefficiency here, but for the foreseeable future most product engineering teams will find themselves doing some level of tracking to support capitalization.

Trying Tailscale.

Like most folks working in infrastructure engineering in 2014, I really enjoyed Google’s BeyondCorp whitepaper. My foremost personal interest was grounded in the fact that Uber’s contemporaneous security implementation didn’t include a VPN, so it was interesting to see a well-thought description of fostering security without over-reliance on a hardened network for employee devices. I had a second, longer-term, personal interest as well, which was never again having to argue with a coworker about why they needed to log into the VPN before accessing a secure resource.

For both of those reasons, I’ve been following Tailscale with interest, and set aside some time to setup a personal Tailscale environment, including setting up their Golink tool to get a feel for it. These are my notes from that experience.

Initial set up

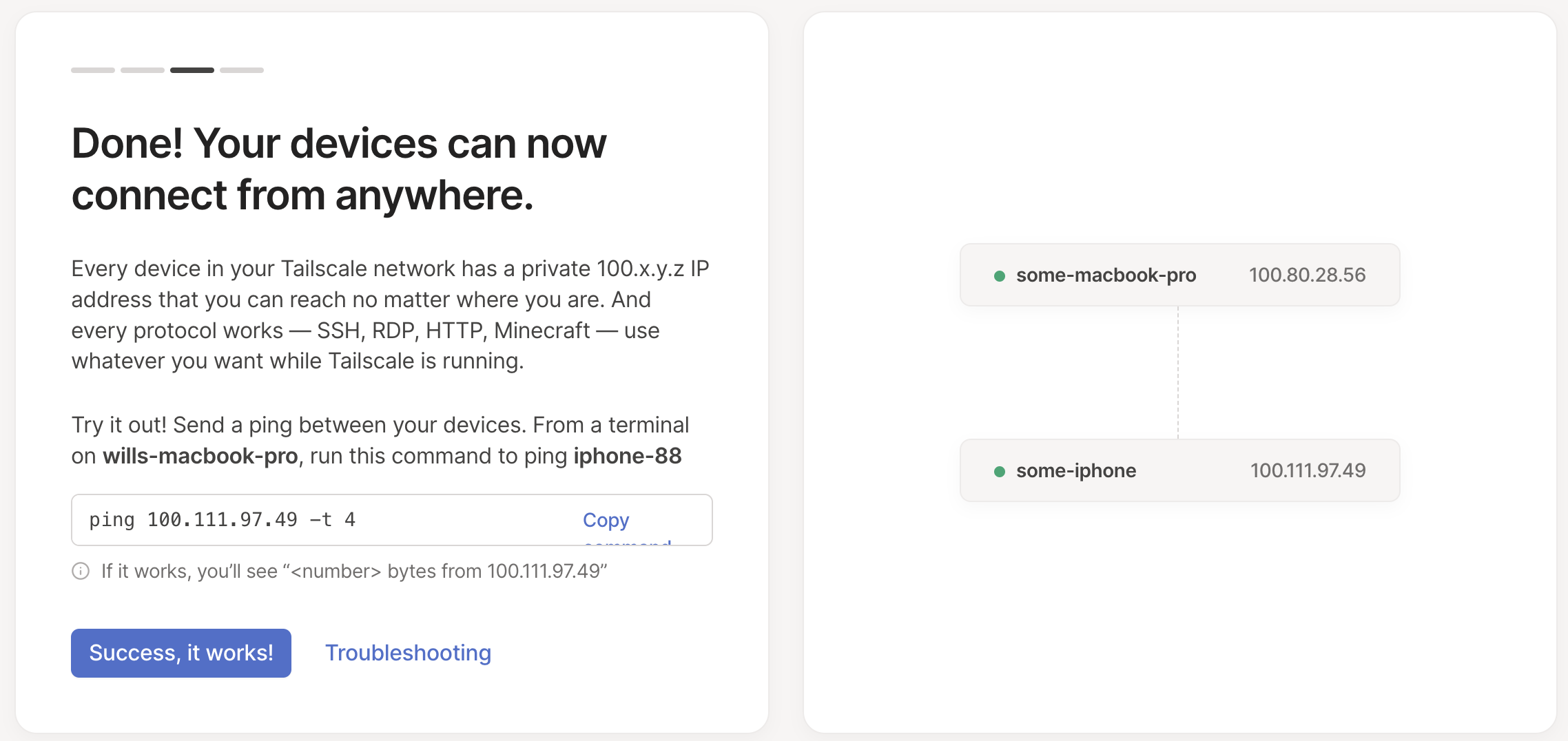

I signed up following the “Use Tailscale” button on the pricing page, using the free Personal plan. At that point, I had to select an identify provider, where I selected Google.

Next, I was asked to download the client for OS X for my computer, which pulled me over to the App Store to handle the installation, which was quick and intuitive. Then I opened the signup email on my phone, which linked me a download page for the mobile client, and was able to quickly install that as well.

Once I’d setup my phone, the website automatically refreshed to show the second device, and prompted me to send a ping.

Pretty excitingly, this actually worked! This was a genuinely delightful setup experience. Within a few minutes, I’ve been able to privately connect two devices, without almost no setup.

Exposing local port over VPN

Now that I had the basics running, I wanted to test connecting to a local instance of my blog via the VPN. First, a quick confirmation that this doesn’t work.

curl 100.80.28.56:1313

curl: (7) Failed to connect to 100.80.28.56 port 1313 after 3 ms: Connection refused

OK, that makes sense because the blog is binding to localhost rather than an externally accessible ethernet interface. Let’s try to change that, going from

hugo -D serve

to instead running

hugo -D --bind 0.0.0.0 serve

Web Server is available at http://localhost:1313/ (bind address 0.0.0.0)

Now I’ll try that curl again:

curl 100.80.28.56:1313 | head -n2

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en-us">

And it works! Let’s also verify we can access it from my phone, which is probably the more interesting test: that works too! Although all the links in Hugo itself don’t work because they are using absolute URLs with localhost, but that’s a Hugo problem (that I imagine is a minute or two of Googling to fix), not a Tailscale one. Pretty neat!

Can I get friendlier DNS?

Typing out 100.80.28.56 is slightly annoying,

so I was curious if I could get friendlier DNS names.

It turned out that this already worked, e.g. some-macbook-pro:1313 already went to my

blog served off my laptop (although it took a few tries to convince mobile Safari it wasn’t

a search query).

(I think this is the “MagicDNS” feature?)

Golinks

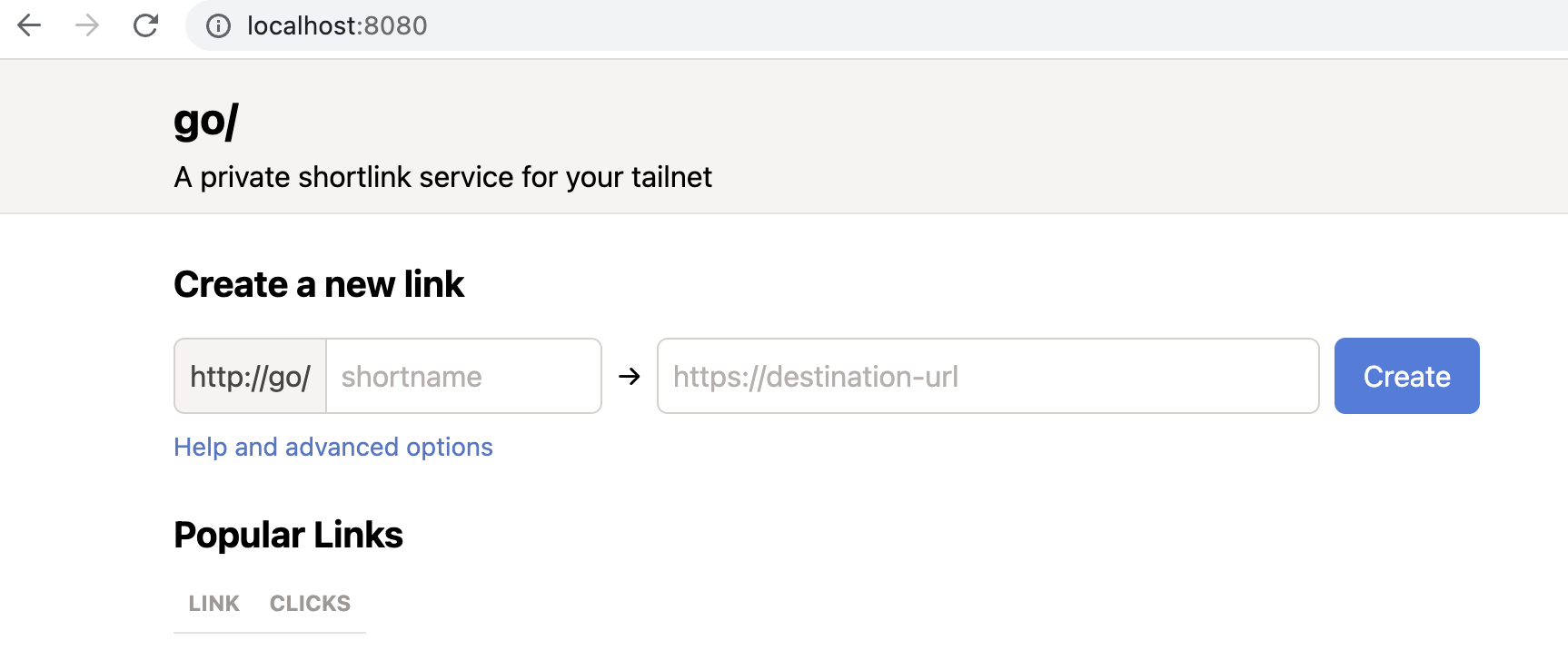

Alright, so at this point I have things working pretty well for the basics, and the next task is setting up their private go links service. I followed along with the instructions in the tailscale/golink repository.

First, I cloned their github repository (as an aside, quick plug for the joys of letting 1Password run your ssh-agent, particularly if your keyboard supports Touch ID):

git clone git@github.com:tailscale/golink.git

Then I built it locally to verify it works:

go run ./cmd/golink -dev-listen :8080

Which failed because I’d forgotten to actually cd into the golink directory.

So then I reran it from the right location, and it worked.

To give it a try, I created a link between write and the Google doc where I keep

a list of topics I want to write about, then verified it worked by going to

localhost:8080/write, which redirected me as expected.

Next step is getting this thing exposed to my phone as well, starting by creating an auth key.

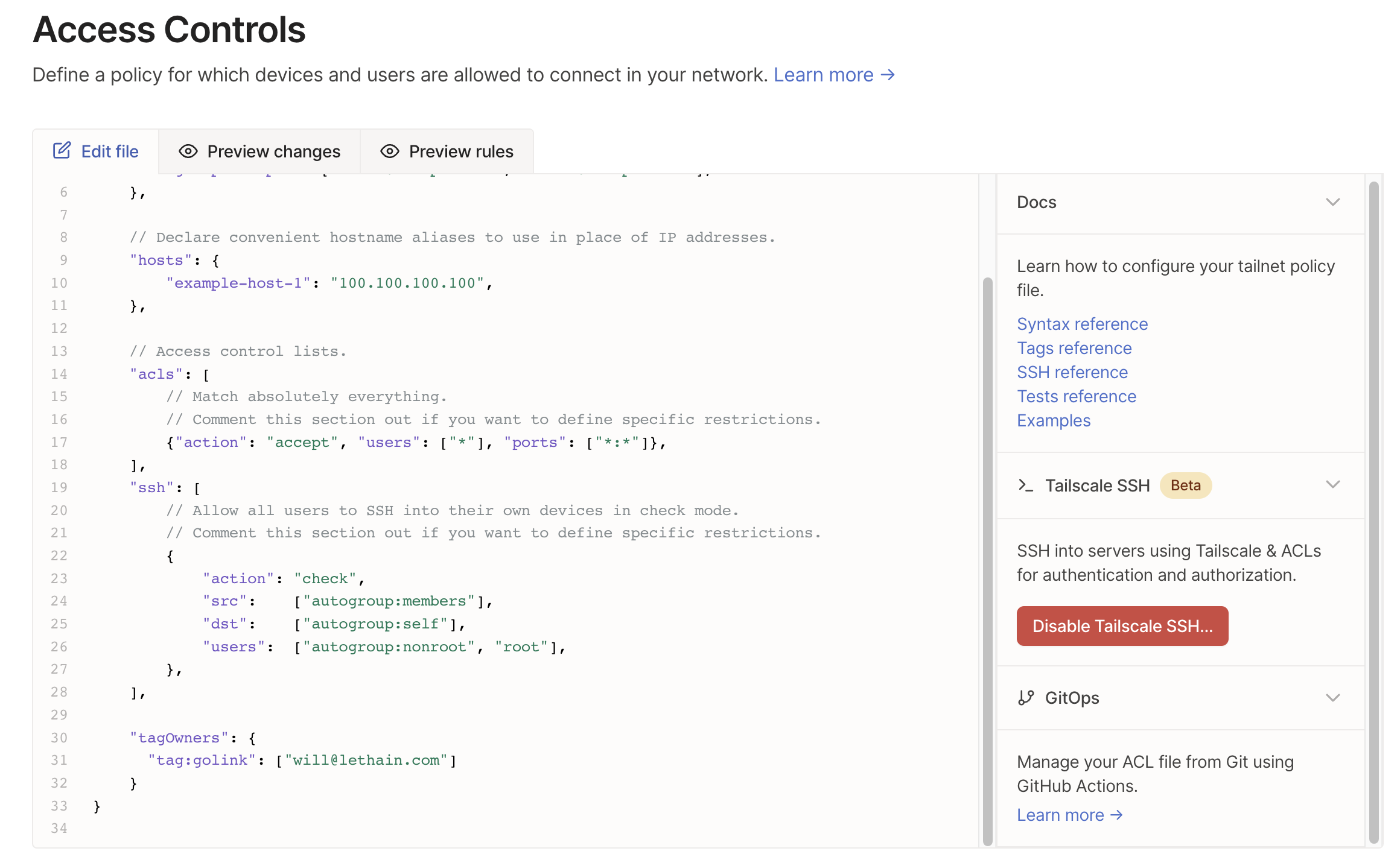

Ok, before creating the key I need to create an ACL tag, and after clicking around at random for a bit I’m not sure how to do that, so I guess I have to read the support article. Oh no, I have to manually edit my policy by hand to accomplish this, that’s mildly concerning.

Hmm, that seems to have worked! So now back to creating an auth key.

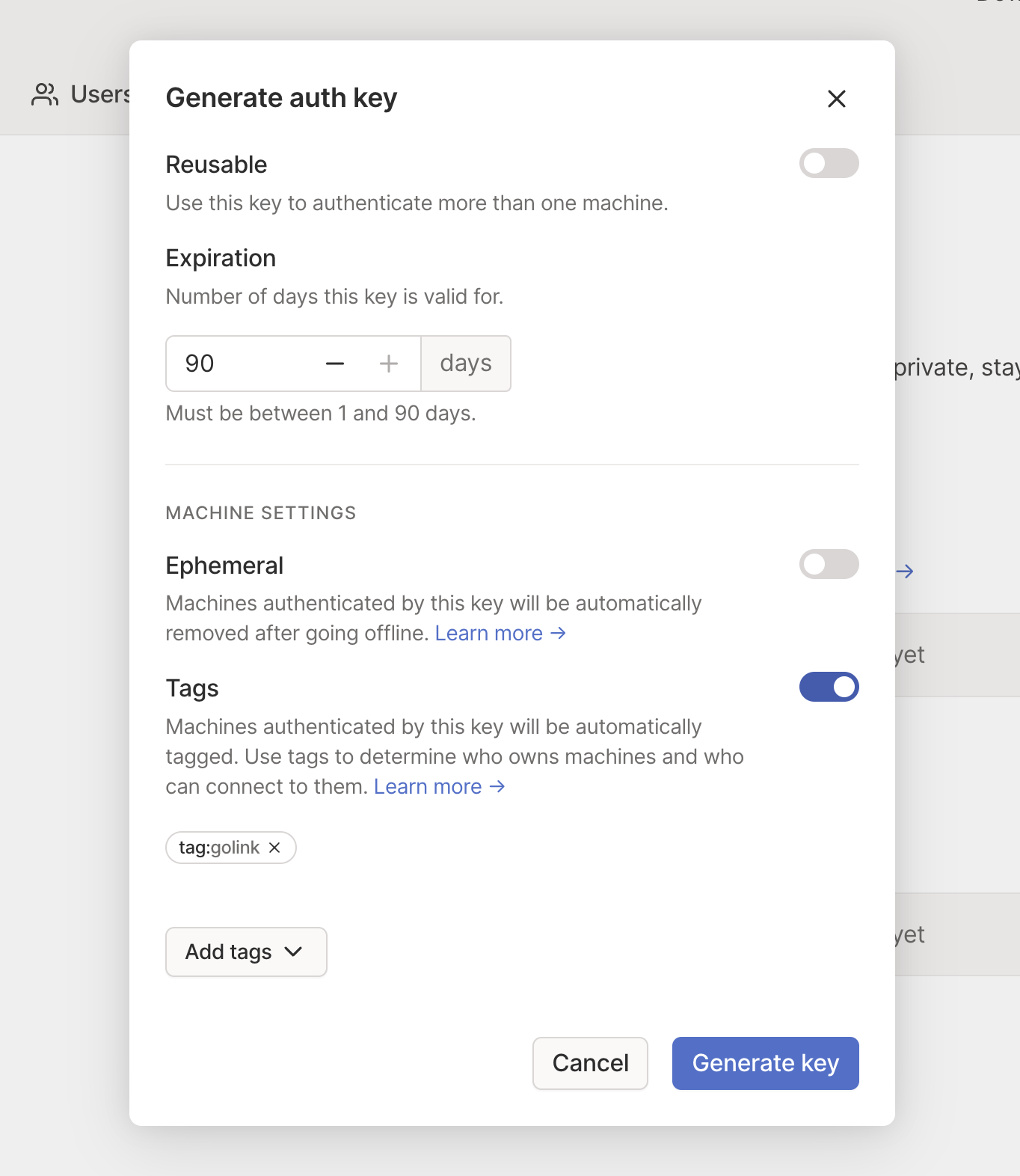

It’s straightforward to add the new tag:golink tag. The only thing I don’t quite understand is how to

follow the instructions saying I should eliminate the key expiration (the UI enforces a 1 to 90 setting),

but that’s fine, just going to power through that one.

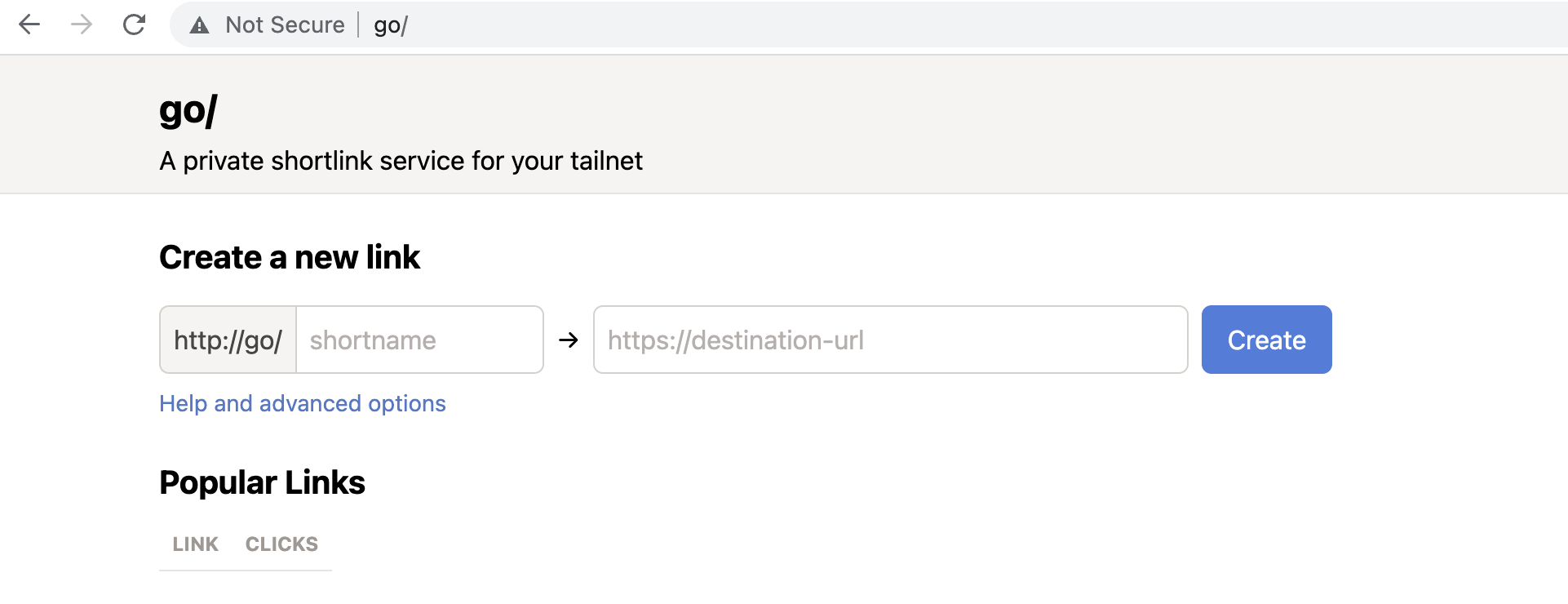

Now that I have my key, I restart the service using

TS_AUTHKEY="tskey-auth-<key>" go run ./cmd/golink -sqlitedb golink.db

The server boots up cleanly, and then the final test is to go to go/ in my browser

and to see if that works.

And it does work, accessible both from my laptop and my phone. Mission accomplished!

As a side note, when I return to the Machines tab, it does appear that key expiry is disabled for this service,

although I have no idea why it’s disabled, maybe because I added a tag?

Not a deal breaker by any means, I am sure I could dig in a bit to figure it out, but it does stand out as one of the two places where I experienced a non-sequitor in my experience.

What was confusing?

All of the issues I found confusing are very minor, and reflective of being a totally new user. Further, I was able to resolve them quickly, without asking for help, which highlights that generally Tailscale is very well put together. Nonetheless, for completeness sake I’ll list them:

- Why is the expiry disabled on my golinks service? Is it because I added a tag? If so, why does the expiration UI still show up as enabled, if the value there is being ignored?

- When I wanted to add a tag to my new auth key, it didn’t direct me towards the resources where I can create a tag. True, it did direct me towards the knowledge base article on the topic, which is OK, but would have loved to have been directed to the policy editor

- I find the placement of auth key issuing UI to be a bit counter-intuitive (Setting, Personal Settings, Keys).

I expected a link from

Access Controlstab to issuing keys.

What was good?

Overall, I think Tailscale is a delightful experience. It was quick to install, the UI was intuitive, the right documentation was almost always one click away. Most importantly, it was easier to get working myself than to get most corporate VPNs setup and working, while playing nicely with my existing SSO providers.

Overall, if I was setting up a personal VPN for myself or a small business, I can’t imagine using something other than Tailscale, it’s simply quite nice. Similarly, if I am building a new developer or infrastructure product in 2023, this is an onboarding (and overall) experience that’s worth borrowing from. (I suspect that it gets much more interesting once you start managing a real policy file, but I’ll leave that for another day!)

So far, it seems like Tailscale is doing an excellent job of expanding marketshare by growing with their existing users, but I’d love to see more from Tailscale push on how companies can use Tailscale to simplify both their security and their compliance controls (SOC2, HITRUST, etc). Figuring out a clear value proposition wrt improving one of these dimensions is their most likely path to increased enterprise adoption, which I imagine will be important to their long-term growth. (You can certainly argue that price is another way they could compete with existing vendors, but ugh, I don’t think you want to be competing on price in the VPN market.)

That's all for now! Hope to hear your thoughts on Twitter at @lethain!

|

Older messages

Meetings for an effective eng organization. @ Irrational Exuberance

Friday, January 20, 2023

Hi folks, This is the weekly digest for my blog, Irrational Exuberance. Reach out with thoughts on Twitter at @lethain, or reply to this email. Posts from this week: - Meetings for an effective eng

Measuring an engineering organization. @ Irrational Exuberance

Wednesday, January 4, 2023

Hi folks, This is the weekly digest for my blog, Irrational Exuberance. Reach out with thoughts on Twitter at @lethain, or reply to this email. Posts from this week: - Measuring an engineering

A brief rant on converging compliance regimes. @ Irrational Exuberance

Wednesday, December 28, 2022

Hi folks, This is the weekly digest for my blog, Irrational Exuberance. Reach out with thoughts on Twitter at @lethain, or reply to this email. Posts from this week: - A brief rant on converging

Lessons not worth learning. @ Irrational Exuberance

Wednesday, December 21, 2022

Hi folks, This is the weekly digest for my blog, Irrational Exuberance. Reach out with thoughts on Twitter at @lethain, or reply to this email. Posts from this week: - Lessons not worth learning.

2022 in review. @ Irrational Exuberance

Friday, December 16, 2022

Hi folks, This is the weekly digest for my blog, Irrational Exuberance. Reach out with thoughts on Twitter at @lethain, or reply to this email. Posts from this week: - 2022 in review. - 2019 - 2022

You Might Also Like

Is it bad to have too many options?

Saturday, March 1, 2025

Meet the Paradox of Choice ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

[Electric Speed] Am I making a mistake?

Saturday, March 1, 2025

Plus: easy meeting scheduling | LA & Yosemite travel tips ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Community Seats for March 2025 to May 2025

Saturday, March 1, 2025

50 % off the Regular Price — Thank you for Being a Subscriber! ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

• 30-Day Book Promo Package • Insta • FB Groups • Email Newsletter • Pins

Saturday, March 1, 2025

Newsletter & social media ads for books. Enable Images to See This "ContentMo is at the top of my promotions list because I always see a spike in sales when I run one of their promotions. The

New Course Live: Experimentation-Led GTM

Friday, February 28, 2025

A Go-to-Market Framework That Never Fails ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

The Phone Game I Shouldn't Promote Because You'll Get Addicted

Friday, February 28, 2025

Help my spread my love of sharing by... uh, also sharing.

Chapter 3: Dynamic Societies

Friday, February 28, 2025

The third chapter from the documentary I'm creating is now live. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

🎤 The SWIPES Email (Friday, February 28th, 2025)

Friday, February 28, 2025

The SWIPES Email Friday, February 28th, 2025 An educational (and fun) email by Copywriting Course. Enjoy! Swipe: This is a handy little graphic that shows the different ways you can use the Grok

How a Medium Writer Evolved Into Bigger Business

Friday, February 28, 2025

$7 for her first article triggered this realization. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Instagram Book Promotion for Authors and Publishers

Friday, February 28, 2025

Your book on Instagram! Instagram promo image Instagram ~ a great place to advertise books