Net Interest - Boutique Wars

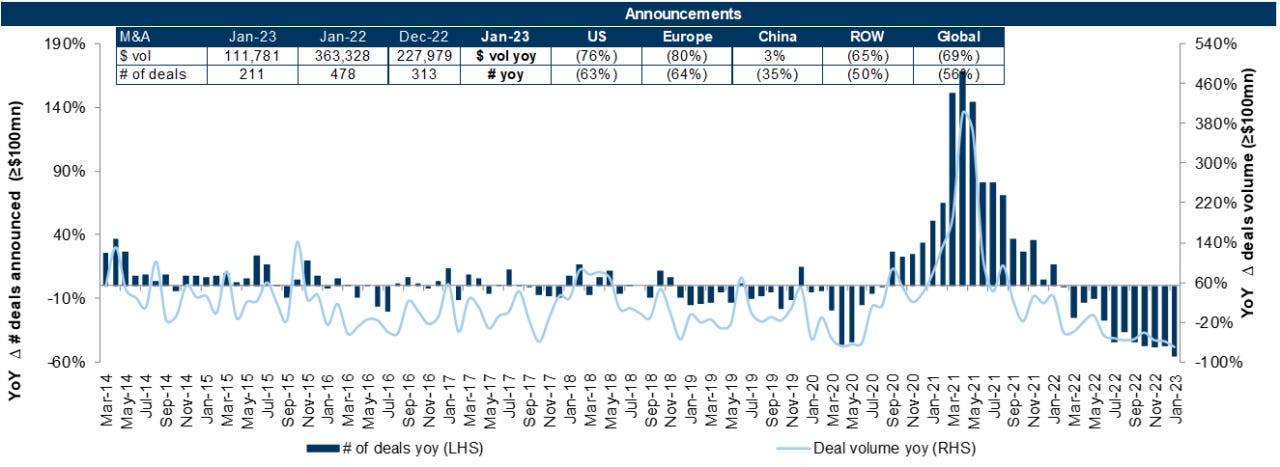

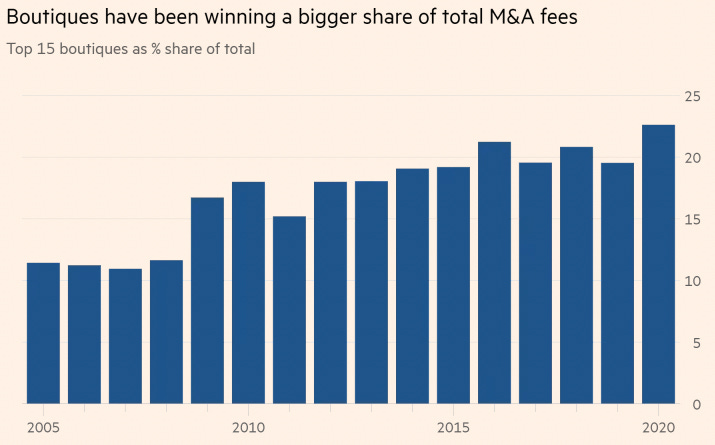

Welcome to another issue of Net Interest, my newsletter on financial sector themes. This week we look at the M&A advisory business through the lens of one of the oldest players in the game, Rothschild & Co. We look at the economics of the business, the competitive dynamics and how a family-owned firm like Rothschild has managed to remain successful. Paying subscribers also get access to comments on short selling response letters, Tether and Credit Suisse (sigh). To join them and unlock that content as well as a fully searchable archive of 100+ issues, please sign up here: For a few years in the late nineties, I worked at one of Britain’s oldest merchant banks, Schroders. Almost 200 years old, it was initially set up by J Henry Schroder to finance cross border trade between America and Europe and fund major infrastructure projects. Over time, it shifted its focus towards corporate advice. In the 1980s, the bank played a leading role in the wave of privatisations carried out in the UK and by the time I got there, it was doing the same in Europe. The legacy of the firm was apparent to all who entered its offices. Portraits of J Henry Schroder and his descendents hung on the top floor of its headquarters at 120 Cheapside. One of them, Bruno Schroder, remained a director of the bank and his nephew, Philip Mallinckrodt, would regularly pass by my desk. The firm had gone public in 1959 but between them, the family still owned a 48% stake. The firm also retained many of its historic traditions. Coffee was served only in the morning, tea in the afternoon; and senior employees would be hand-delivered a copy of the London Evening Standard by a staff butler in time for their commute home. Yet while the firm had clawed out a viable niche for itself providing advice and procuring financing for mergers, acquisitions, divestitures and other corporate reorganisations, it found itself losing ground to US competitors. Corporate clients were increasingly looking for the kind of global service provided by large investment banks and Schroders lacked that scale. So the firm decided to sell. At the beginning of 2000, I was called into a departmental meeting where management announced the group was selling its investment banking business to Citigroup for a consideration of $2.2 billion. “We are too small to be big, too big to be small,” said the bank’s president. Schroders wasn’t the first mid-sized bank to succumb to a takeover by a larger rival. In the preceding years, Morgan Grenfell had been acquired by Deutsche Bank, Kleinwort Benson by Dresdner Bank (now part of Commerzbank) and SG Warburg by Swiss Bank Corporation (now part of UBS). A short while after Schroders sold to Citigroup, Robert Fleming (founded 1873) announced its sale to Chase Manhattan (now part of JP Morgan). Pull up a league table of UK investment banking activity from the early 1980s and most names have been subsumed into larger, global banks. There is one exception: Rothschild & Co. Like Schroders, it was a family run bank with roots in eighteenth century Germany. While the Schroders focused on international trade, the Rothschilds were initially involved in financing governments and in dealing with foreign exchange and bullion. But over the years, both migrated towards corporate advice and, by the 1990s, both were struggling with the same competitive pressures from US firms. This week, Rothschild & Co announced it is to double down on its family legacy. The company has had a stock market listing in Paris for many years, but its new executive chairman, the seventh generation of the family to take charge, has launched a bid to take it fully back into family hands. The motivation to get bigger is a compelling one, but over centuries, Rothschild has shown that in the market for corporate advice, there is more than one strategy to pursue… The M&A BusinessAdvising companies on merger and acquisition (M&A) activity is one of the highest profile jobs in finance. It emerged alongside a general rise in M&A in the 1980s. In 1981, Stanford Law School professor, William Baxter, took a job in Ronald Reagan’s administration on the proviso that he could introduce a more lenient antitrust policy. “There is nothing written in the sky that says the world would not be a perfectly satisfactory place if there were only 100 companies,” he said. Under Baxter’s influence, the US Antitrust Division did not intervene when companies tried to make an acquisition. Soon, many made M&A a plank in their strategy and investment banking firms were there to provide advice. Before long, banks proactively proposed mergers and acquisitions to expansionist companies and their business took off. Unlike other areas of investment banking, M&A advisory is not a capital intensive business. It is constrained by the quality of the advisors it employs and the relationships they cultivate. But it can be very lucrative because fees are linked to deal size, while base costs are linked to labour. This is a very different model from that of other professional services firms like law firms, where services are remunerated according to how much time the supplier spends on the job. The top M&A law firm globally is New York headquartered Simpson Thacher & Bartlett. In 2021, it generated $2.2 billion of total revenue. The top M&A advisory firm is Goldman Sachs; in 2021, it earned $5.7 billion of advisory fees. In a typical M&A deal, fees can be 0.50-0.60% of deal size. While they are generally lower for larger deals, costs don’t rise in proportion, so the largest deals can be very lucrative. Fees tend to be higher in the US than in Europe (a common feature across many areas of financial services). The reason could be that in the US, M&A advice is sufficiently career-changing for a CEO that price is not the primary consideration; in Europe, by contrast, the decision may be treated more like a commercial procurement. For a successful M&A business, the economics can be very attractive. Robey Warshaw is a London-based firm founded in 2013. It has advised on a number of the UK’s largest deals including BG Group’s sale to Royal Dutch Shell, Comcast Corp’s winning bid for Sky and London Stock Exchange Group’s purchase of Refinitiv. With just 13 employees in its financial year to the end of March 2022, it earned revenue of £39.8 million, equivalent to over £3 million per head. Its operating margin after administrative expenses was a very high 76%, leaving £30.1 million to be shared out in profit among its four partners. Of course, ratchet up the fixed costs and the results can be disastrous. Before selling to Citigroup, Schroders attempted to beef up its US presence alone. A number of hires were made but the firm’s London-based management neglected existing clients, failed to attract new ones and lost control of the cost base. The result was $25 million of losses. Difficulties are compounded by the cyclical nature of the industry. M&A activity is a derivative of the economic cycle. It is correlated to the equity markets and to levels of CEO confidence. The cycle tends to lag markets by around three to four months. Unsurprisingly given these factors, 2021 was a record year for M&A activity, with 2022 showing a corresponding decline. Not all the data is yet in for 2022, but on the basis of the first nine months, global M&A fees were tracking down 12%, after hitting around $40 billion in 2021. A particular trend within the market over the past 15 years has been the rise of specialist boutique firms. When Schroders sold to Citigroup in 2000, it was because clients wanted to use bigger, more global firms. These firms were also able to tap up their commercial clients for advisory work. In 2016, JP Morgan disclosed that 40% of its North American investment banking fees derived from commercial banking customers. But tighter regulations and pay restrictions in the aftermath of the financial crisis made the model less appealing for bankers, while the perception of conflicts of interest made it less appealing for clients. As a result, specialist M&A boutiques have gained share. Many of these boutique firms were founded by émigrés of the large banks. Senior bankers from Morgan Stanley went on to set up both Robey Warshaw in London and PJT Partners in New York. Other boutiques include Greenhill & Co, Evercore, Moelis & Company, Perella Weinberg Partners, Houlihan Lokey, Lazard and Rothschild & Co. Between them, boutique firms grew their share of M&A fees from around 10% in 2006 to over 20% by 2020.

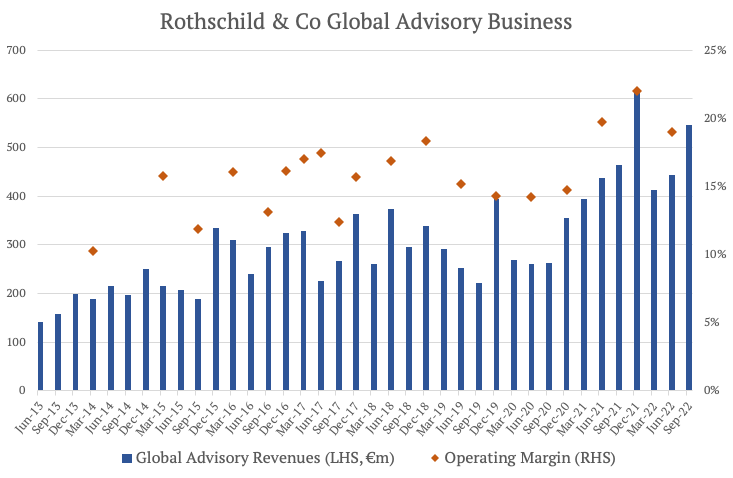

But the battle between independent firms and integrated banks is an ongoing one. Ten years after overseeing the Schroders deal, the man who ran it for Citigroup, Michael Klein, left to launch his own firm, M. Klein & Co. Like Robey Warshaw, it is small and discrete – its website comprises a single page and it employs just 40 people. Since 2010, it has advised on $1.5 trillion of transactions. This week Credit Suisse announced that it is buying the firm at a valuation of $210 million, taking Klein out of the boutique bracket and back into the integrated bracket. ¹ Wells Fargo is also keen to flex its muscles as an integrated bank. This week, it poached a new global head of M&A from Morgan Stanley. Like JP Morgan before it, Wells Fargo has identified an opportunity to cross-sell investment banking products into its commercial client base. The bank’s goal is to capture some of the $4.5 billion in fees it estimates that its clients pay to other firms on Wall Street each year. Throughout it all, though, one firm has remained steadfastly committed to the boutique model. It’s had its challenges over the years but Rothschild & Co has ranked number one in European M&A for the past 15 years. By number of deals it ranked first globally in 2022 – one of only two first to have done over 300 deals last year – and just outside the top ten by value. By taking it private, the family reckons it can align interests more closely. “None of the businesses of the Group needs access to capital from the public equity markets. Furthermore, each of the businesses is better assessed on the basis of their long-term performance rather than short-term earnings,” it states in its press release. The House of RothschildAt its peak, Rothschild was anything but a boutique. “For a contemporary equivalent, one has to imagine a merger between Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, JP Morgan and probably Goldman Sachs too – as well, perhaps, as the International Monetary Fund, given the nineteenth-century Rothschilds’ role in stabilising the finances of numerous governments,” wrote historian Niall Ferguson in The House of Rothschild: The World’s Banker. But its path was not smooth. Between the eve of the First World War and the conclusion of the Second World War, capital at the London arm of the bank contracted from £8 million to £1.5 million. With the gold price now fixed and the centre of global capital flows having shifted from London to New York, Rothschild lost several of its competitive advantages. Struggling with its positioning in this new environment, Jacob Rothschild declared in 1965 that “We must try to make ourselves as much a bank of brains as of money.” One aspect of this new strategy was a push into advisory work. Apart from a couple of minor share issues in the late 1940s, little had previously been done in this area. The firm refused to become involved in steel “denationalisation” when Churchill proposed it in 1953; nor was it involved in the battle for British Aluminium in 1959, the first hostile takeover of a public company in the UK. That changed in the 1960s when the bank made a concerted effort to bolster relationships with UK corporations. Although it failed in its first mandate in 1961 – the defence of Odhams Press from a takeover by the Daily Mirror – Rothschild went on to advise on a string of winning deals. By 1968, the firm ranked eighth in domestic M&A league tables, advising on £370 million worth of transactions. Two years later, it was up to fifth. The French arm of the bank, meanwhile, adopted a different strategy. Under the leadership of Guy de Rothschild, the bank’s goal was to compete with commercial banks by raising deposits – to “collect more and more liquidities from the broadest possible clientele in the widest possible area,” as he put it. Through a series of acquisitions, the bank had grown its branch network to 21, its headcount to 2,000 and its assets to 13 billion Francs, equivalent to around £1.3 billion. By 1980, Banque Rothschild was the tenth largest deposit bank in France. At the same time, both the Paris and London sides of the family cooperated on global expansion. In 1969, they each injected capital into a new entity, Rothschild Intercontinental Bank. The bank organised a $100 million loan to Mexico and looked for other opportunities abroad. However, in the wake of the oil crisis, business dried up and the bank was sold to Amex International for £13 million in 1975. Soon after, the French strategy also faltered. In 1981, a new socialist government led by François Mitterrand moved to nationalise the country’s banks. Thirty-nine of them, including Banque Rothschild, were caught in the net. Although the family was compensated, the bank’s profitability was poor and so the proceeds were limited. With the help of London, the Paris branch of the family soon got back on its feet. Within three years of nationalisation, the family reemerged on the scene via a holding company, Paris-Orléans Gestion. When Mitterand lost his parliamentary majority in 1986, corporate finance activity took off in France and the new bank was there to help, abandoning any ambitions to raise deposits in favour of the boutique strategy of offering corporate advice. By then, the London branch had paved the way for the boutique strategy. Margaret Thatcher’s election as prime minister in 1979 heralded a wave of company privatisations in the UK. From its very inception, Rothschild had specialised in meeting the financial needs of governments and although this was traditionally via bonds, the firm was quick to leverage its heritage into advising on the sale of government assets. Echoing its first foray into corporate finance 20 years earlier, Rothschild didn’t win on its first attempt, being passed over for the 1979 government sale of BP shares. But in 1982, it handled the first true privatisation when the government floated its 100%-owned high tech company Amersham International on the stock market. Rothschild went on to advise British Gas on its £6 billion public offering in addition to many more. As foreign governments followed the British example towards privatisation, Rothschild’s expertise was sought overseas. In 1988, it handled 11 privatisations in eight different countries. And in France, the Paris arm advised the government on the flotation of French bank Paribas. In spite of its success, not all Rothschilds were enamoured with the boutique strategy. In a rift on the London side of the family, Jacob Rothschild left the firm in 1980 to branch out on his own. For a long time, he’d wanted to merge Rothschild with another bank so that it might be able to offer a wider range of financial services. In a speech in 1983, he predicted that, as international financial deregulation continued, “the two broad types of giant institutions – the worldwide financial service company and the international commercial bank with a global trading competence – may themselves converge to form the ultimate, all-powerful, many-headed financial conglomerate.” Via his investment company, RIT, Jacob Rothschild attempted to create such a conglomerate. He acquired a number of assets including 50% of (unrelated) New York investment bank L.F. Rothschild, Unterberg, Towbin and 30% of London broker Kitcat & Aitken, merging everything with the Charterhouse Group to form Charterhouse J. Rothschild. The combined market capitalisation of the new group was £400 million – more than double the size of the Rothschild bank, run by his cousin Evelyn. But it pretty quickly unravelled. A deal to merge with Hambro Life in 1984 failed and the group’s stock price sank. Jacob Rothschild sold off his banking stakes to refocus on his investment management interests within RIT. In the years that followed, the French and British arms of the bank each pursued a boutique strategy independent of each other. Eventually, in 2012, they reunited in a merger engineered through the Paris Orléans listed vehicle. According to the head of the French arm, David de Rothschild, the new structure would “allow the bank to better meet the requirements of globalisation in general and in our competitive environment in particular, while ensuring my family’s control over the long term.” Since then, the bank has performed well. It is active in wealth and asset management and has a number of private investments, but advisory remains its largest business, contributing two-thirds of the group’s revenues. M&A is the biggest component of that. In the last 12 months, the firm earned €1.5 billion in fees from M&A. But the bank also earns fees from debt advisory, restructuring and equity markets solutions which contribute another €0.5 billion to its revenues. Unlike Robey Warshaw, bankers are paid through direct compensation rather than via a share of profits, so Rothschild’s reported margin is lower. In the global advisory segment, bankers take home around 80% of the revenues they generate, leaving the balance for the outside shareholders (and the taxman) including the family. Rothschild’s consistency at the top of the league tables has handed the firm a more stable profit stream. In the good years, the operating margin has been as high as 22%; in the bad years it has dropped to only 10%. The family is taking the company out at a valuation of €3.7 billion. They already own 38.9% and are in talks with partners to raise financing for the rest. At 7.1 times earnings it looks like a good deal for them. But by eliminating a currency for their own mergers or acquisitions, they reduce their capacity to bulk up. Two hundred years in, it looks like the Rothschilds are in the boutique game for the long haul. Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this piece, please hit the “Like” button. Better yet, join the community by signing up as a paid subscriber! 1 According to Credit Suisse, the $175 million headline consideration comprises a convertible note whose principal amount is expected to be $100 million, with the balance being paid in cash dependent on the tax consideration to be paid by the seller at closing. Together with annual payments on the note and other considerations, the $175 million purchase price has a net present value of approximately $210 million. For Klein, as majority owner of the firm, this is a very good deal. But it is somewhat flaky: Michael Klein was on the board of directors of Credit Suisse; he led the investment bank strategy review (and billed CS for this) which decided CS would buy his company; and now he becomes the new CEO of CS First Boston while taking seat on the CS executive board. You’re on the free list for Net Interest. For the full experience, become a paying subscriber. |

Older messages

The Art of Short Selling

Friday, February 3, 2023

Plus: Deutsche Bank, Custodia Bank, Late Fees

Growing Visa

Friday, January 27, 2023

Plus: Charles Schwab, Equity Research, Railsr

Broker Rivalry

Friday, January 20, 2023

Plus: Discount Window, Play the Music, Japanese Banks

The Bank that Never Sold

Friday, January 20, 2023

Plus: Net Interest Margins, Frank, BlackRock

Insuring the Unknown

Friday, January 6, 2023

Plus: Blackstone, Crypto Banks, Citadel Securities

You Might Also Like

Longreads + Open Thread

Saturday, March 8, 2025

Personal Essays, Lies, Popes, GPT-4.5, Banks, Buy-and-Hold, Advanced Portfolio Management, Trade, Karp Longreads + Open Thread By Byrne Hobart • 8 Mar 2025 View in browser View in browser Longreads

💸 A $24 billion grocery haul

Friday, March 7, 2025

Walgreens landed in a shopping basket, crypto investors felt pranked by the president, and a burger made of skin | Finimize Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March 8th in 3:11 minutes.

The financial toll of a divorce can be devastating

Friday, March 7, 2025

Here are some options to get back on track ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Too Big To Fail?

Friday, March 7, 2025

Revisiting Millennium and Multi-Manager Hedge Funds ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

The tell-tale signs the crash of a lifetime is near

Friday, March 7, 2025

Message from Harry Dent ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

👀 DeepSeek 2.0

Thursday, March 6, 2025

Alibaba's AI competitor, Europe's rate cut, and loads of instant noodles | Finimize TOGETHER WITH Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March 7th in 3:07 minutes. Investors rewarded

Crypto Politics: Strategy or Play? - Issue #515

Thursday, March 6, 2025

FTW Crypto: Trump's crypto plan fuels market surges—is it real policy or just strategy? Decentralization may be the only way forward. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

What can 40 years of data on vacancy advertising costs tell us about labour market equilibrium?

Thursday, March 6, 2025

Michal Stelmach, James Kensett and Philip Schnattinger Economists frequently use the vacancies to unemployment (V/U) ratio to measure labour market tightness. Analysis of the labour market during the

🇺🇸 Make America rich again

Wednesday, March 5, 2025

The US president stood by tariffs, China revealed ambitious plans, and the startup fighting fast fashion's ugly side | Finimize TOGETHER WITH Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March

Are you prepared for Social Security’s uncertain future?

Wednesday, March 5, 2025

Investing in gold with AHG could help stabilize your retirement ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏