Hi there, it’s Mehdi Yacoubi, co-founder at Vital, and this is The Long Game Newsletter. To receive it in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

🎧 I sat down recently with the great and wise Sam Sager to talk about health, over-optimization, fitness, and of course, playing The Long Game™️

You can listen to the episode here.

| Training for the Long Game with Mehdi Yacoubi Sam Sager Episode |

In this episode, we explore:

Let’s dive in!

Last week I marked six months without alcohol for me. I’m used to having on & off periods, but this is the longest I’ve gone without alcohol. Before I share some of the benefits, I want to preface this by saying I don’t drink much in regular times, maybe 3—5 drinks per week on average.

Here are some of the benefits I’ve experienced:

Less fatigue overall. I rarely, if ever, have this feeling of just needing a day off because I’m too tired

Less money spent at the restaurant : )

Sleep quality has been better, even if the other parameters are not optimal (for example, even with a late meal, I manage to get good sleep with enough deep sleep)

No/less loss of momentum: waking up with a slight hangover is a giant momentum killer, makes you feel awful, and question your life decisions when it wasn’t necessary

Less weight gain: alcohol comes with useless calories; removing it makes sticking to your calorie target easier (this wasn’t so much a big deal for me as I’ve been bulking for almost two years, but it’s always good to be able to eat more vs. restrain food to add some drinks)

More muscle gain (as a function of being able to handle more volume/train harder)

Better overall recovery from training: even with just a few drinks per week, I felt my overall recovery from training was slower.

Healthier skin (ps: you don’t need expensive skincare products; try dropping the 🍻 — 😅)

Lower RHR & higher HRV, although this could be the consequence of more HIIT cardio and not only dropping alcohol

Now I’m not going to sit here and ignore the other side of the topic. Even though for me it’s almost entirely beneficial in my current life context, I think in some different contexts, it could be a net positive (if you know how not to go overboard.)

Alcohol is great in social contexts and can significantly enhance some moments with friends. The problem is that consumption over time tends to increase for many people, from 1—2 drinks 1—2 times per week to 3—5 drinks 3—4 times per week. A trend that I’ve seen time & time again.

Pair with: What Alcohol Does to Your Body, Brain & Health

Key takeaways from the episode:

Chronic alcohol intake, even at low to moderate levels (1-2 drinks per day or 7-14 per week), can disrupt the brain

When people drink, the prefrontal cortex and top-down inhibition are diminished, and impulsive behavior increases – this is true in the short term while drinking and rewires circuitry outside of drinking events in chronic drinkers (even those who drink 1-2 nights per week, long term)

Damaging effects to the prefrontal cortex and rewiring of neural circuitry are reversible with 2-6 months of abstinence for most social/casual drinkers; chronic users will partially recover but likely feel long-lasting effects.

People who start drinking at a younger age (13-15) are more likely to develop dependence, regardless of the history of alcoholism in their family; people who delay drinking to their early 20s are less likely to develop an addiction, even if there’s a family history.

People who drink consistently (even in small amounts, i.e., 1 per night) experience increases in cortisol release from adrenal glands when not drinking, so they feel more stress and anxiety when not drinking.

With increased alcohol tolerance, you get less and less of the feel-good blip and more and more of the pain signaling (so behaviorally, you drink more to try to activate those dopamine and serotonin molecules again)

The risk of breast cancer increases among women who drink – for every 10 grams of alcohol consumed per day, there’s a 4-13% increase in the risk of cancer (alcohol increases tumor growth & suppresses molecules that inhibit tumor growth)

Regular consumption of alcohol increases estrogen levels in males and females through aromatization.

On this topic, I’ve been following the growth of non-alcoholic or low-alcoholic alternatives, as I believe it will be the future. Fitt Insider had a great issue about it.

In 2019, alcoholic beverage sales in the US surpassed $250B.

But there’s a catch: 43% of drinking-age Americans don’t consume alcohol. And 40% say they’re drinking less than they did five years ago.

Driving this trend, 66% of US millennials said they’re making efforts to reduce their alcohol consumption, citing motivating factors like well-being and weight loss. A sign of what’s to come, Gen Z is consuming less alcohol than previous generations.

Globally, the World Health Organization expects the proportion of drinkers to fall by 1.4 percentage points to 40.3% between 2020 to 2025.

This a great & essential follow-up to the piece I shared two weeks ago.

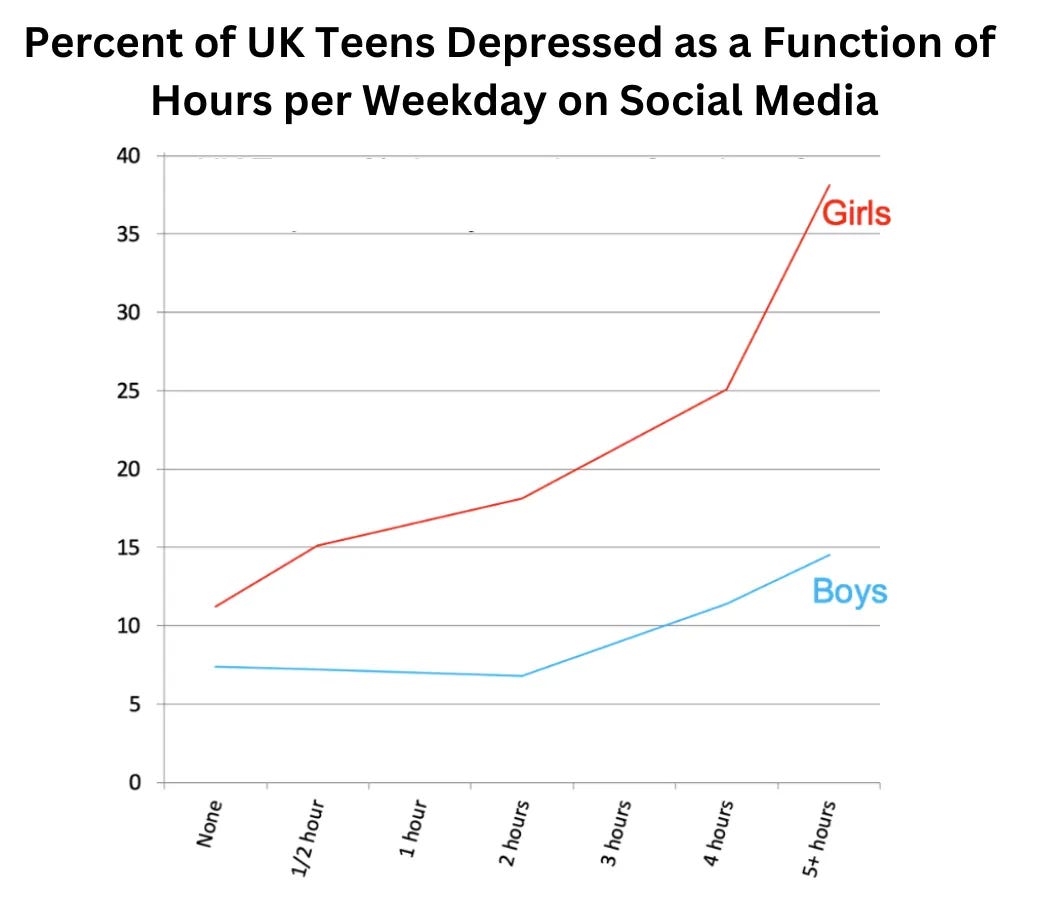

A big story last week was the partial release of the CDC’s bi-annual Youth Risk Behavior Survey, which showed that most teen girls (57%) now say that they experience persistent sadness or hopelessness (up from 36% in 2011), and 30% of teen girls now say that they have seriously considered suicide (up from 19% in 2011). Boys are doing badly too, but their rates of depression and anxiety are not as high, and their increases since 2011 are smaller. As I showed in my Feb. 16 Substack post, the big surprise in the CDC data is that COVID didn’t have much effect on the overall trends, which just kept marching on as they have since around 2012. Teens were already socially distanced by 2019, which might explain why COVID restrictions added little to their rates of mental illness, on average. (Of course, many individuals suffered greatly).

Most of the news coverage last week noted that the trends pre-dated covid, and many of them mentioned social media as a potential cause. A few of them then did the standard thing that journalists have been doing for years, saying essentially “gosh, we just don’t know if it’s social media, because the evidence is all correlational and the correlations are really small.” For example, Derek Thompson, one of my favorite data-oriented journalists, wrote a widely read essay in The Atlantic on the multiplicity of possible causes. In a section titled Why is it so hard to prove that social media and smartphones are destroying teen mental health? he noted that “the academic literature on social media’s harms is complicated” and he then quoted one of the main academics studying the issue—Jeff Hancock, of Stanford University: “There’s been absolutely hundreds of [social-media and mental-health] studies, almost all showing pretty small effects.”

In this post, I will show that Thompson’s skepticism was justified in 2019 but is not justified in 2023. A lot of new work has been published since 2019, and there has been a recent and surprising convergence among the leading opponents in the debate (including Hancock and me). There is now a great deal of evidence that social media is a substantial cause, not just a tiny correlate, of depression and anxiety, and therefore of behaviors related to depression and anxiety, including self-harm and suicide.

Here’s the TL;DR:

7. Conclusion: Social Media Is a Major Cause of Mental Illness in Girls, Not Just a Tiny Correlate

We are now 11 years into the largest epidemic of teen mental illness on record. As the CDC’s recent report showed, most girls are suffering, and nearly a third have seriously considered suicide. Why is this happening, and why did it start so suddenly around 2012?

It’s not because of the Global Financial Crisis. Why would that hit younger teen girls hardest? Why would teen mental illness rise throughout the 2010s as the American economy got better and better? Why did a measure of loneliness at school go up around the world only after 2012, as the global economy got better and better? (See Twenge et al. 2021). And why would the epidemic hit Canadian girls just as hard when Canada didn’t have much of a crisis?

It’s not because of the 9/11 attacks, wars in the middle east, or school shootings. As Emile Durkheim showed long ago, people in Western societies don’t kill themselves because of wars or collective threats; they kill themselves when they feel isolated and alone. Also, why would American tragedies cause the epidemic to start at the same time among Canadian and British girls?

There is one giant, obvious, international, and gendered cause: Social media. Instagram was founded in 2010. The iPhone 4 was released then too—the first smartphone with a front-facing camera. In 2012 Facebook bought Instagram, and that’s the year that its user base exploded. By 2015, it was becoming normal for 12-year-old girls to spend hours each day taking selfies, editing selfies, and posting them for friends, enemies, and strangers to comment on, while also spending hours each day scrolling through photos of other girls and fabulously wealthy female celebrities with (seemingly) vastly superior bodies and lives. The hours girls spent each day on Instagram were taken from sleep, exercise, and time with friends and family. What did we think would happen to them?

The Collaborative Review doc that Jean Twenge, Zach Rausch and I have put together collects more than a hundred correlational, longitudinal, and experimental studies, on both sides of the question. Taken as a whole, it shows strong and clear evidence of causation, not just correlation. There are surely other contributing causes, but the Collaborative Review doc points strongly to this conclusion: Social Media is a Major Cause of the Mental Illness Epidemic in Teen Girls.

A few stories worth reading.

William Vanderbilt was one the richest heirs to ever live. But hold your envy – his life was hardly a joy.

Just before he died in 1920, Vanderbilt told the New York Times, “My life was never destined to be quite happy. Inherited wealth is a real handicap to happiness. It is as a death to ambition as cocaine is to morality.”

The interesting thing is that the other end of the spectrum – an overdose of ambition – may be just as miserable.

A half-century before, Mark Twain wrote to William Vanderbilt’s grandfather, Cornelius Vanderbilt:

How I pity you, and this is honest. You are an old man, and ought to have some rest, and yet you have to struggle, and deny yourself, and rob yourself restful sleep and peace of mind, because you need money so badly. I always feel for a man who is so poverty ridden as you.

Don’t misunderstand me, Vanderbilt, I know you have $70 million. But then you know and I know, that it isn’t what a man has that constitutes wealth. No – it is to be satisfied with what one has; that is wealth.

A few good reads on consumer social:

Collective Experiences

Humans are wired to connect with others and shared context is the foundation. How do we find shared context? Shared experiences, or the often more impactful collective experiences. But in a mostly digital, remote world, collective experiences feel ever rare. The IRL ones (e.g. going to a live concert) even feel nostalgic now.

Instead, digital media has become core to the modern collective experience. We binge tv shows the weekend they premiere, watch live streams from our favorite creators, share TikTok videos, and scroll through friends’ social posts. Then we talk about it with each other. Digital media is our main source of shared context.

And as technology increasingly offers on-demand, personalized experiences, things that we experience together become even more valuable. So what are collective experiences and what makes them so valuable? How do consumer products create modern collective experiences? And why does this matter now?

Social products win with utility, not invites

Today’s social startups don’t start off as networks. They start off as standalone apps. These products enable users to create a corpus of content first. They then connect the users with each other as a consequence of sharing that content.

Instagram started out as a photo-taking tool and built itself out into a social network subsequently. The initial focus was entirely on the creation of content and the connections were formed over time leveraging other social networks. It is unlikely that Facebook would have considered Instagram a direct competitor in its early days, largely owing to its model of deferring network creation.

How to create a network in stealth mode

Instagram started off as a standalone tool. In doing so, the product provides ‘single-user’ utility to the user even when other users aren’t around on the network.

An Interview with Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger About Artifact

I think a couple things that really help — one is that Artifact isn’t a product where if your friends aren’t on it’s just not interesting and if they never join, it’s never going to be interesting. There’s a lot of great content out there that’s getting produced every day and we find people that even who might kick the tires, site it’s not working for them yet, do come back later. Sometimes it’s a week, some days it’s months. Sometimes we’re like, “Wow, this person showed back up.” It’s not like we learned anything more about them in the meantime, but we learned enough about people like them that the product got better or we added some new sources that were useful.

Two is push notifications, which we try to be thoughtful and smart about what we actually send to people, but that’s a great other way in which people like maybe a week later like, “Oh, that actually is a really good story that I want to click on”, and “Hey, the feed got better for these different reasons”. So hopefully we get people in and there’s always a group that’s going to stick. Then what’s kind of fun about Artifact that’s a bit different than Instagram is we got these other touch points over time that might be a trigger point for somebody checking it out again. Maybe we have some new announcement where they’ll bring it back in and I think as long as people give us enough tries over time I’m confident we keep getting better.

Pair with:

Tim Urban is great, and he just released a book called What’s Our Problem. I started listening to it last week, and it doesn’t disappoint.

Between 2013 and 2016, Tim Urban became one of the world's most popular bloggers, writing dozens of viral, long-form articles about everything from AI to colonizing Mars to procrastination. Then, he turned his attention to a new topic: the society around him. Why was everything such a mess? Why was everyone acting like such a baby? When did things get so tribal? Why do humans do this stuff?

This massive topic sent Tim tumbling down his deepest rabbit hole yet, through mountains of history, evolutionary psychology, political theory, neuroscience, and modern-day political movements, as he tried to figure out the answer to a simple question: What's our problem?

Six years later, he emerged from the hole holding this book. What's Our Problem? is a deep and expansive analysis of our modern times, in the classic style of Wait But Why, packed with original concepts, sticky metaphors, and 300 drawings. The book provides an entirely new framework and language for thinking and talking about today's complex world. Instead of focusing on the usual left-center-right horizontal political axis, which is all about what we think, the book introduces a vertical axis that explores how we think, as individuals and as groups. Readers will find themselves on a delightful and fascinating journey that will ultimately change the way they see the world around them.

Anyway he wanted to say a lot more about all of this but there was a word limit on this book description so just go read the book.

“When it comes to HRV, less is more.”

The utility of HRV is in measuring our stress response, i.e. what happens in our body hours after the stressors. That’s why it is useful, if we respond well, it normalizes and is stable, if it stays suppressed, something went wrong or other stressors played a role.

Measuring in a known context (e.g. first thing in the morning, hours after stressors, and after the restorative effect of sleep), allows us to capture just that: the response. This makes the data meaningful and actionable (see an example below).

Measuring all the time, not only provides often noisy, de-contextualized, and possibly meaningless data (e.g. not even related to parasympathetic activity) but does not answer the main question we are interested in: it is not about the response anymore.

When it comes to HRV, less is more.

The destruction of more traditional forms of community led many people to direct their own fate through identity-based associations. These associations revolved around everything from class and gender to religious and dietary preferences. There were civil societies, economic interest groups, scientific interest groups, professional societies, paramilitary groups, and philosophical organizations. And each group proclaimed that its cause was singularly important for Germany’s future. Due to these competing interests and identity groups, “Imperial Germany, like other industrial societies,” writes historian Brett Fairbairn, “was not a comfortable place or well-integrated whole.”

Among the more popular of these groups were those that fell under the large and unwieldly umbrella of the life-reform movement, or Lebensreform, a loose confederation of vegetarians, nudists, anti-vivisectionists, gymnosophists, naturopaths, and other back-to-nature types. This motley band varied widely in their political and philosophical beliefs. Uniting many of them, however, was an interest in an esoteric philosophy called monism.

“how my bf got Instagram Reels-pilled”

The Girl Internet is where all of the important things happen. It is where culture is born, where social norms are litigated, aesthetics are christened and slang terms defined. It is where unfathomably powerful fandoms collide and whose explosions have ricocheting consequences for the rest of the world. The Girl Internet is where people talk about that New York Magazine article on Fleishman or that New York Magazine article on etiquette or thatNew York Magazinearticle on nepo babies. Again, the Girl Internet is not just for women, rather it is simply one framework with which I view the vast landscape of two subsets of internet culture that rarely, if ever, bump into each other, except for on Twitter during like, the Oscars or the Super Bowl.

Somehow, despite living with and being in a longterm relationship with someone whose job is somewhat predicated on having deep knowledge of the visual-first platforms favored by the Girl Internet, Luke has never once downloaded TikTok. Recently, however, he has been spending a great deal of time on Instagram Reels. Part of me feels quite triumphant about this, because I have been writing about how addicting this kind of content is for as long as we’ve been dating, and until now he’s been staunchly repelled by it.

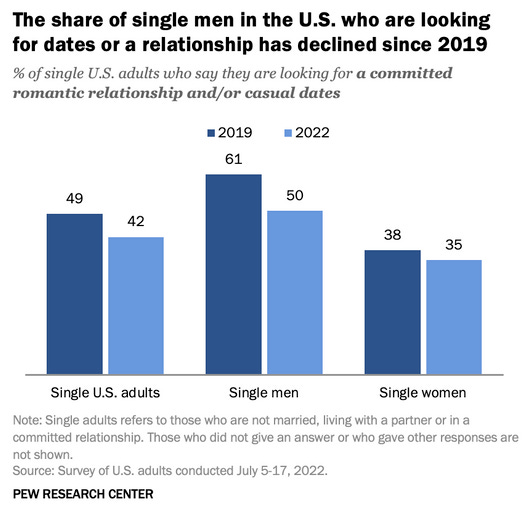

Men today are much less interested in romantic relationships than in 2019 (50% of them are interested today, 61% in 2019). Women's interest hasn't dropped as much, but they're even less interested than men in absolute terms.

What do you think is causing this?

Pair with: The world of dating is a mess

This a good follow-up to last week’s topic.

One of the (few) drawbacks of lifting is that it gets harder to find good pants. I find that Lululemon pants get the job done and are very comfortable.

The story continues. If you fail on Monday, the only way it’s a failure is if you decide to not progress from that. To me, that’s why failure is not existent. If I fail today, I’m going to learn something from that failure. I’m going to try again.

— Kobe Bryant

Thanks for reading!

If you like The Long Game, please share it on social media or forward this email to someone who might enjoy it. You can also “like” this newsletter by clicking the ❤️ just below, which helps me get visibility on Substack.

Until next week,

Mehdi Yacoubi