|

OHF Weekly, Vol. 5 No. 29: Editor’s Letter, “There Is But One Fight,” “The Groveland Four,” “America Is Drunk on Racism,” and a quote by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Editor’s Letter💛 Hey Reader, Saturday, August 11, Medium will celebrate its eleventh birthday along with its community of readers, writers, and human storytelling with twelve hours of virtual talks, presentations, and panel discussions. And Our Human Family editors and writers have been invited to talk about racial equity, allyship, and inclusion. Our panelists include: Clay RiversOur Human Family Founder and EIC

Story: “If Not Now, White Folks, When?” Sherry KappelOur Human Family Managing Editor

Story: “Let’s Talk Black Excellence, People!” Terra KestrelOur Human Family Writer

Story: “There Is But One Fight” William SpiveyOur Human Family Writer, Historian

Story: “When You’ve Been White Too Long” Save the date: Saturday, August 11, 10:30-11:00 a.m. (Eastern). Bring your favorite espresso drink and a pastry and we’ll see you then. We promise not to promote books, videos, or work schemes to get your email address. But we will share our passion for showing people how we’re more alike than we’re unalike. And we’ll take a few questions, if time allows. Reserve your free ticket now! It takes less than two minutes. Love one another. Clay Rivers

OHF Weekly Editor in Chief

New This WeekThere Is But One FightIf the disease “is greed and the struggle for power,” then it is greed and the struggle for power anywhere that we must fight.By Terra Kestrel  Photo by Saki Busto, Unsplash. They were brown suede booties with zippers and a 2.5-inch heel and they were perfect. It was an effort to find them, but after two days and multiple cities, I finally had shoes that fit me. This was a new experience. Before this, my approach to buying shoes was comprised of the following steps: A) Look for the shoes I want, and B) Buy my size. But something had changed. Finding a size 14 was difficult enough, but even finding them, most did not fit. It was a similar story with other articles of clothing. Sizing of pants went from a simple measurement I could trust to a vague hint in some undecipherable language. The change was not in my body. My feet and waist were the same size. What had changed was how I publicly express my gender. I went from wearing men’s clothes to wearing women’s clothes. With that one change, shopping went from a simple task to one of deliberate and time-consuming complexity. It felt like a set of obstacles had been erected to prevent success in even the most mundane of tasks. The more I thought about my own change and what this represented, the more I realized that it might be true. The best of essays can be distilled into a single sentence. That is because they are a single sentence. If the human mind were something vastly different than it is, a single sentence might be all we ever need. But we need more than a statement of fact, a detailing of evidence. We need a story. Our minds need context. And that is what the essay is: the context that gives the statement its meaning. In 1975, Toni Morrison presented1 such a story to a small group at Portland State University. This little-known speech, called “A Humanist View,” has often been distilled to a fundamental quote: Read the complete article at OHF Weekly.

An American Town Has Not Held an Election in Sixty YearsIn Newbern, Alabama, voter suppression has a particularly egregious manifestation.By Guy D. Nave, Jr.  A 2011 march in midtown Manhattan defending voting rights. WikimediaVoter suppression is a strategy used to influence the outcome of an election by discouraging or preventing specific groups of people from voting. Voter suppression is an anti-democratic tactic associated with authoritarianism.African Americans are the primary target of voter suppression in the United States. Voter suppression has been practiced in the United States since at least the end of Reconstruction (1865–77). After Reconstruction, African Americans living in the former Confederate States were briefly able to exercise their newly won rights to vote; to run for local, state, and federal offices; and to serve on juries. The Fourteenth (1868) and Fifteenth (1870) Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, along with a series of laws passed between 1866 and 1875, attempted to extend to all American men (yes, “men”) the liberties and rights granted by the Bill of Rights. The Fifteenth Amendment specifically prohibited restricting or denying the right to vote on the basis of race. In 1867, nearly three years before the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, Congress passed the Military Reconstruction Act, which brought the vote to Black men in ten former Confederate states. The first year Black men were able to participate in federal elections was 1868. Despite enormous obstacles and violent opposition, by 1868 more than eighty percent of Black men who were eligible to vote had registered. Relying on federal protection, African American voters elected hundreds of Black state representatives and several Black U.S. representatives and senators during Reconstruction. While voter suppression tactics existed during Reconstruction, they increased exponentially after the end of Reconstruction. The tactics of voter suppression range from changes that make voting more confusing or time-intensive, to intimidating or harming prospective voters. One of the most effective ways of suppressing votes is refusing to hold elections. Read the complete article at OHF Weekly.

The Groveland Four: Omitted from Florida’s Black History GuidelinesMuch has been made about the new Florida’s State Academic Guidelines for Black history, for good reason: They ignore critical portions of Black history. 3#By William Spivey  The Groveland Four (from a Florida historical marker). Photo by Carol Spivey. Ron DeSantis knows about the Groveland Four; but Florida’s Board of Education fails to mention it in Florida’s history curriculum. One of DeSantis’s first acts during his first term as Governor was to issue a pardon for the Groveland Four. In his own words, he acknowledged their history had been wrongly told for seventy years. Now he’s removed their history entirely. “For seventy years, these four men have had their history wrongly written for crimes they did not commit. As I have said before, while that is a long time to wait, it is never too late to do the right thing. I believe the rule of law is society’s sacred bond. When it is trampled, we all suffer. For the Groveland Four, the truth was buried. The Perpetrators celebrated. But justice has cried out from that day until this. I would like to thank CFO Patronis, Attorney General Moody, and Agriculture Commissioner Fried for their support.” —Gov. Ron DeSantis, 2019

Much has been made about the new Florida’s State Academic Guidelines for Black history. To be fair, they are far more wide-ranging and inclusive than one might gather without reading the document. They also omit critical portions of Black history, including the Compromise of 1877 and Posse Comitatus, which combined ended the Reconstruction Era. There’s no mention of the partus sequitur ventrem laws, which reshaped enslavement, defining who was a slave. The Groveland Four was left out, presumably because white Floridians don’t look good. Early in my writing career, I met a former classmate from Fisk University at a funeral. I hadn’t seen Malcolm Cunningham, an attorney in South Florida, for thirty years. He was familiar with some of my writings and made a suggestion that changed my perspective on history. He told me to find the non-fiction book, “Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America. It was written by Gilbert King and won a Pulitzer Prize. I heartily recommend it to all; now on with the story. Read the complete article at OHF Weekly.

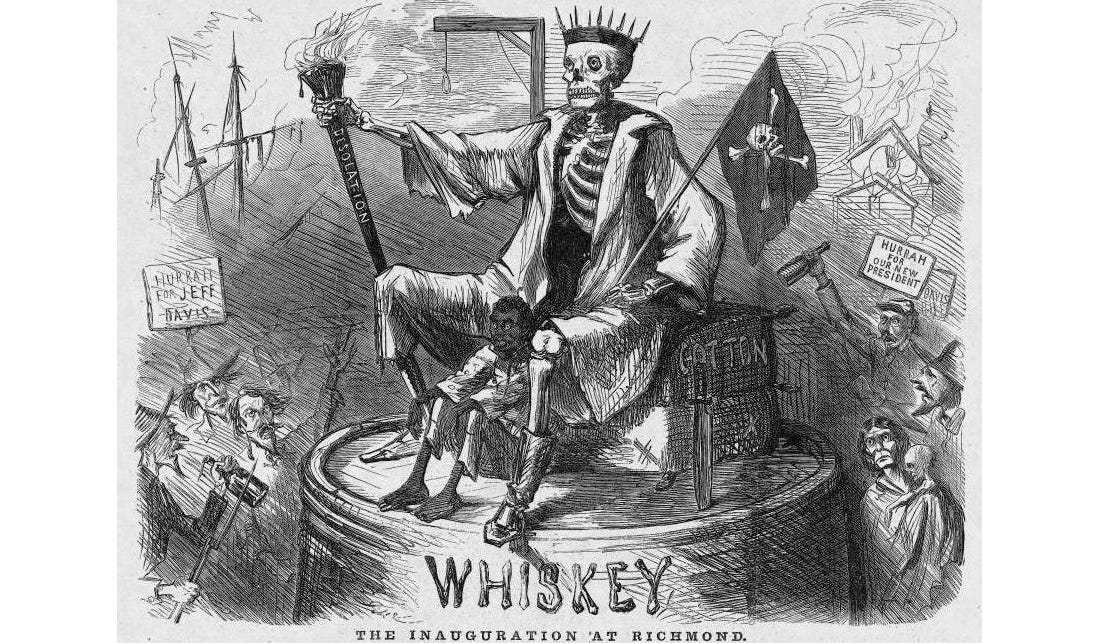

America Is Drunk on RacismToo many Americans are convinced that the only way to experience the high of national pride is to disregard all the evidence of racial inequity.By Walter Rhein A year ago, I got news that a friend of mine, who was known for his partying, had given up drinking. Upon hearing this, it surprised methat of all the emotions I felt, I recall the distinct stab of jealousy. “Why do I feel jealous?” I wondered. If I was living the life I wanted to live, why should I feel envious of a friend who had chosen sobriety? But before I could make further progress, the familiar justifications for drinking rose up to divert me from the path of healthy self-reflection. “I need to be able to wind down in the evenings. I need a break every now and then. Drinking is a part of social settings. It’s just a few beers. I can quit whenever I want.” My internal dialogue became increasingly hostile, as if I was mad at myself for even considering there was anything I needed to change. I found myself asking why the idea of a self-evaluation provoked feelings of denial and anger? What was the mechanism at work that kept me off the path to progress and condemned me to a toxic lifestyle? More importantly, how was it possible to escape this mechanism? I did quit drinking eventually, and my life is better for it. This experience allowed me to recognize how a similar mechanism of self-deception appears whenever there is a social dialogue on the subject of racism. Racism apologists are intoxicated with their perception of our country. They deflect from any mention of racial inequality. Eventually, they become angered that you ever brought it up. The question before us now is how to stage a productive intervention that will help our society develop a true commitment to racial equality. Read the complete article at OHF Weekly.

Final Thoughts

|