|

Two reminders before we get on the brush with Slappy Hooper... Reader SurveyTomorrow, 1 March, is the deadline to share your views on BLAG via this year's reader survey. The prize draw to win a lifetime membership will take place on Saturday at BLAG Meet. BLAG MeetI can't wait to hang out all day with the brilliant group of contributors to BLAG Meet: Inside Issue 04. It's happening online on Saturday, and is free to join for one, some, or all of the sessions. For those that can, a $10 contribution to the technical running costs is appreciated.

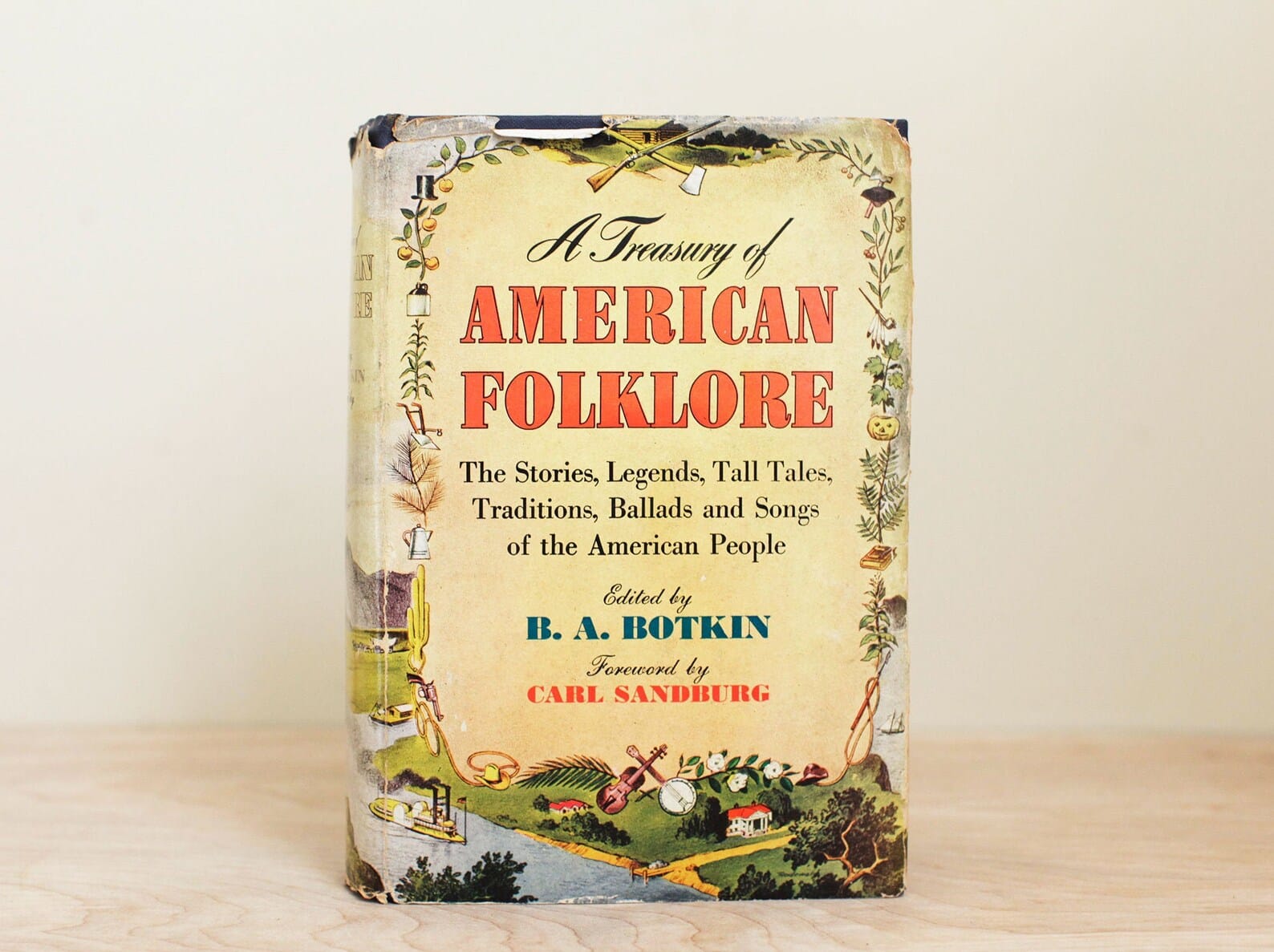

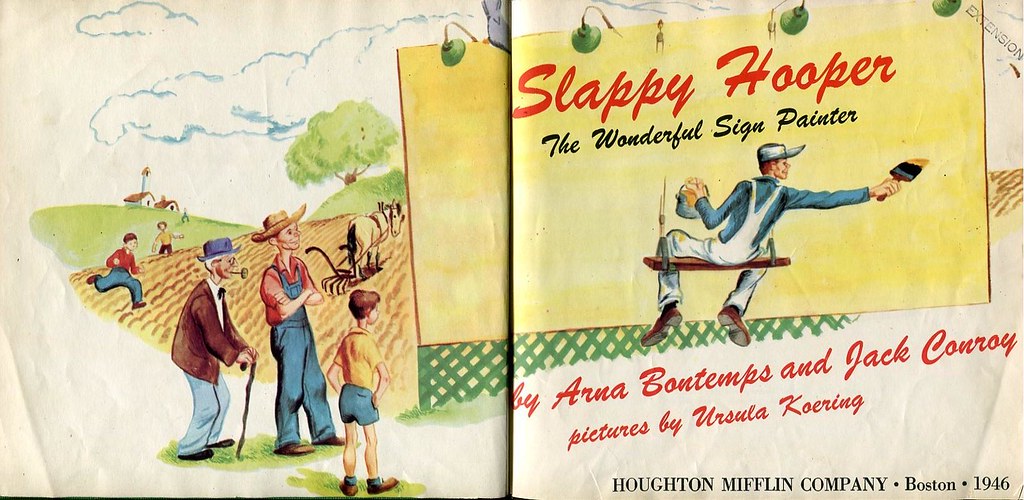

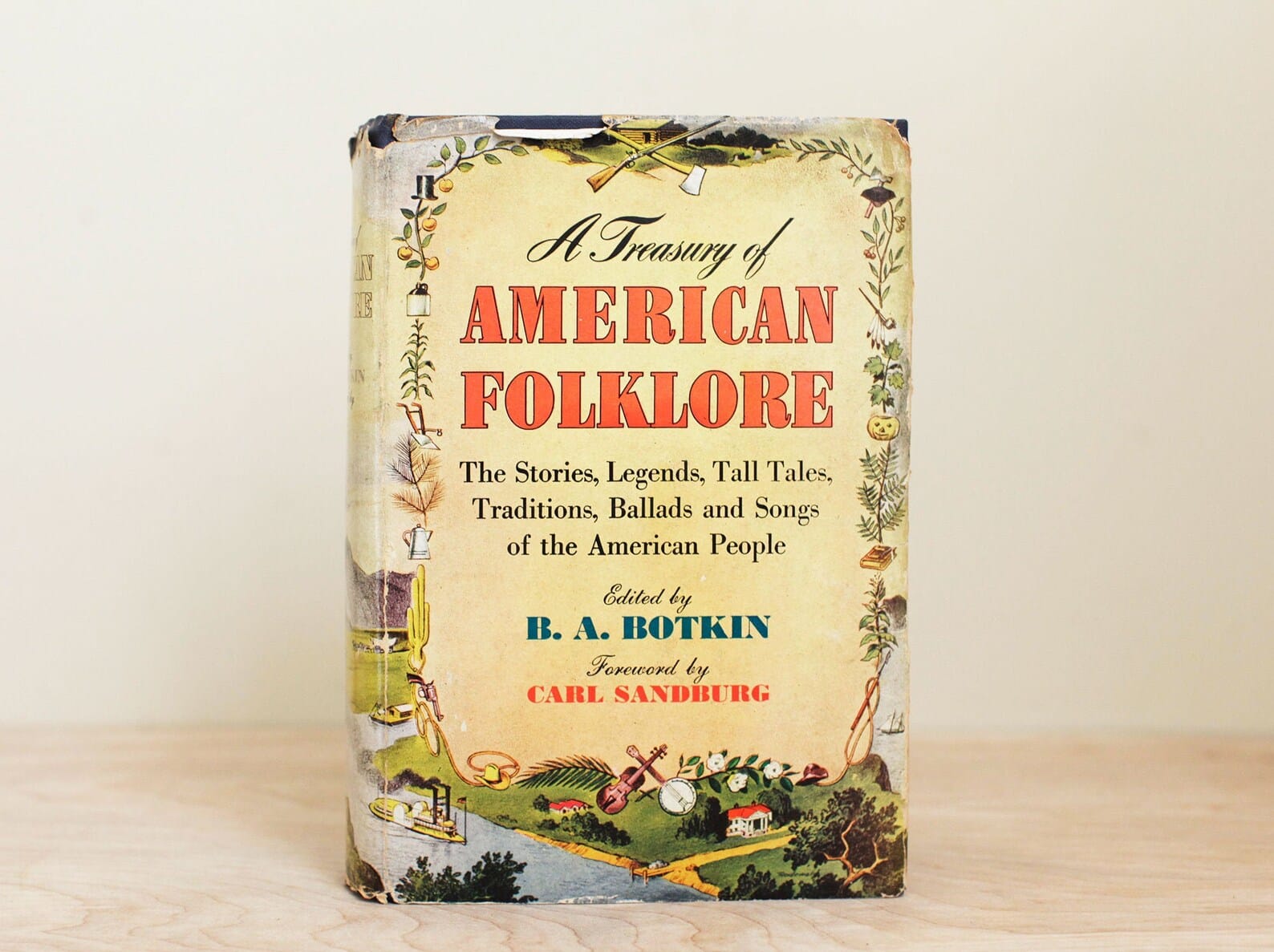

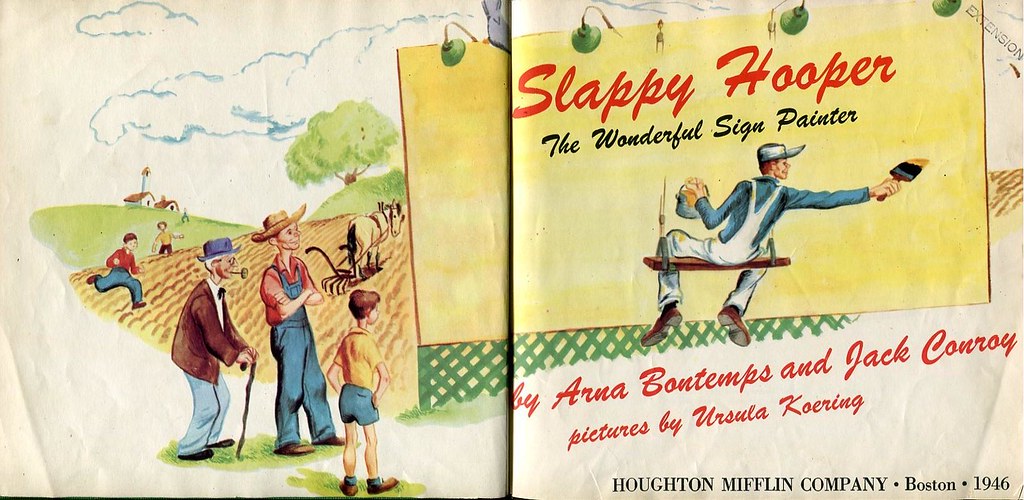

This month saw the reissue of Aaron Shepard and Tony Goffe's picture book, The Legend of Slappy Hooper. It was first published in 1993, but Slappy Hooper's story goes back to the 1930s, as Shepard details in his author note: "The legend of 'Slappy Hooper, World’s Biggest, Fastest, and Bestest Sign Painter' was collected in Chicago in 1938 by Jack Conroy for the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration. It was first published in B.A. Botkin’s A Treasury of American Folklore (Crown, New York, 1944)."  A Treasury of American Folklore, edited by B.A. Botkin. Botkin's book runs to nearly 1,000 pages, just four of which contain the original legend. I tracked down a copy, and have transcribed the story at the end of this post for your enjoyment. Retelling the LegendShepard and Goffe's interpretation is not the only retelling of the Slappy Hooper story. Two years after the Botkin anthology was published, Arna Bontemps worked with Jack Conroy to expand on the legend for a book illustrated by Ursula Koering.

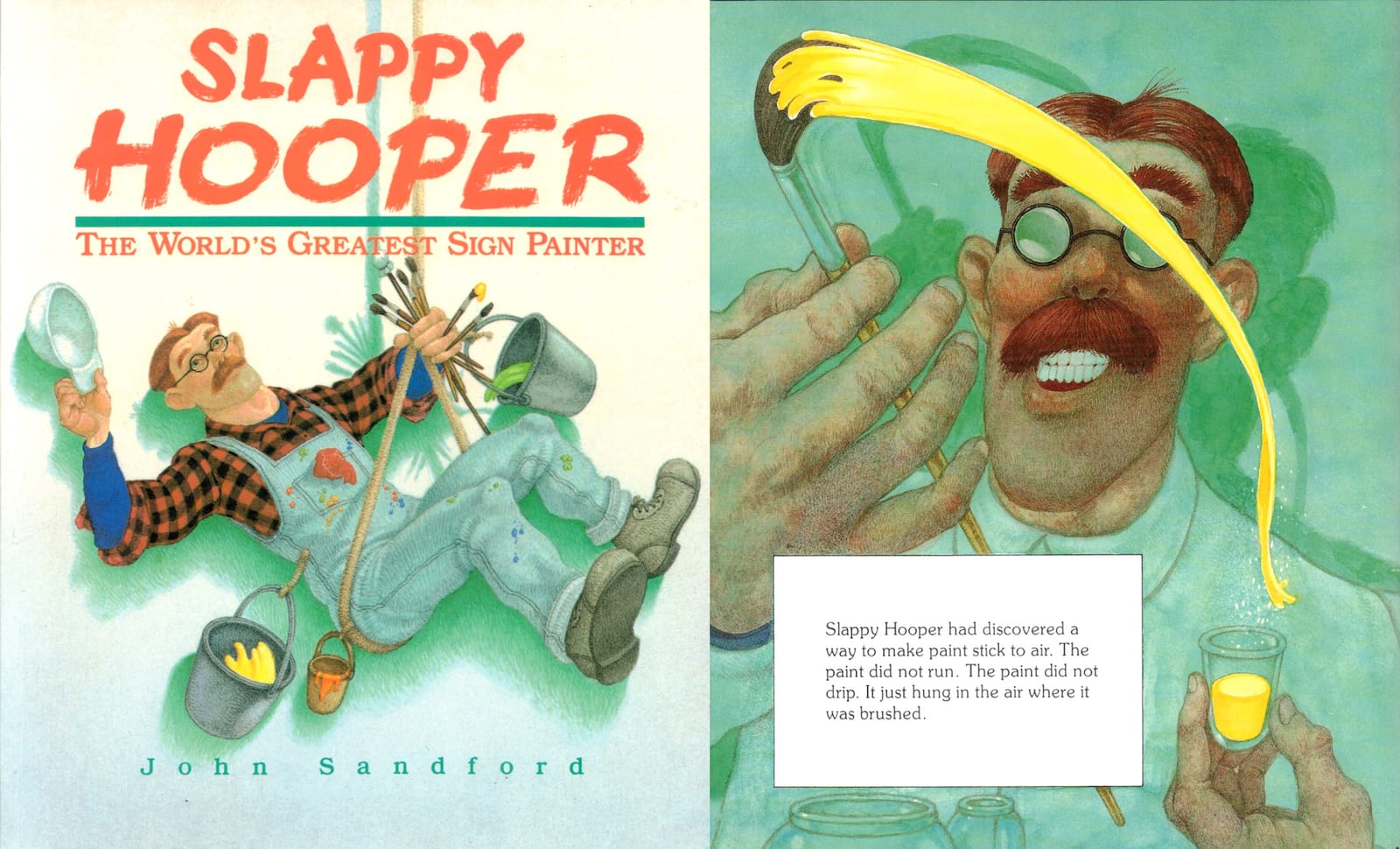

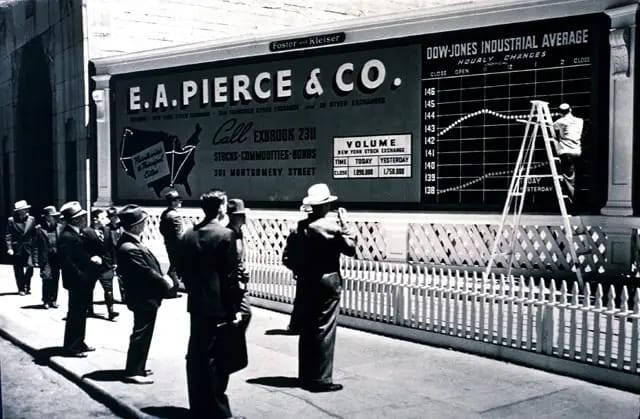

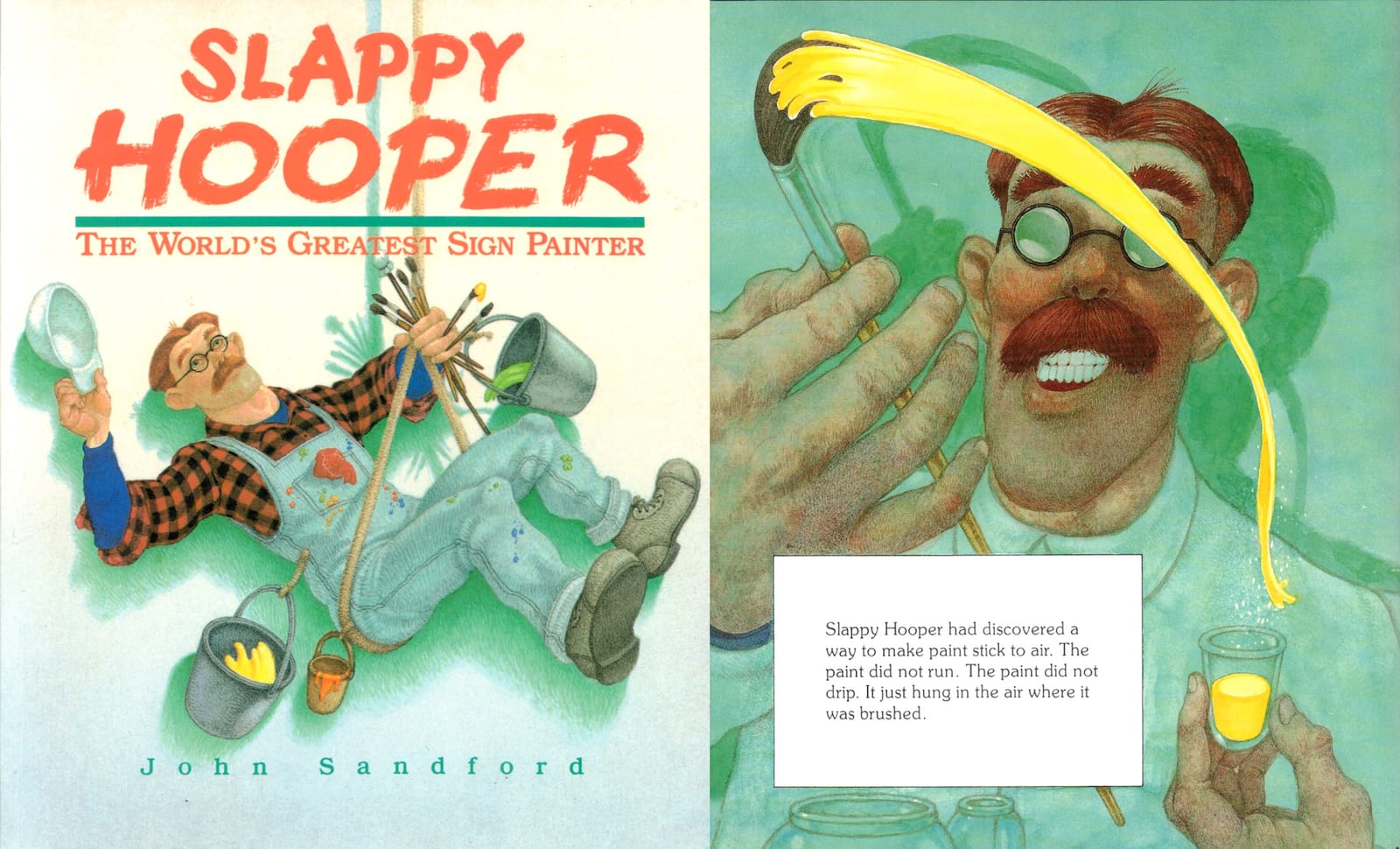

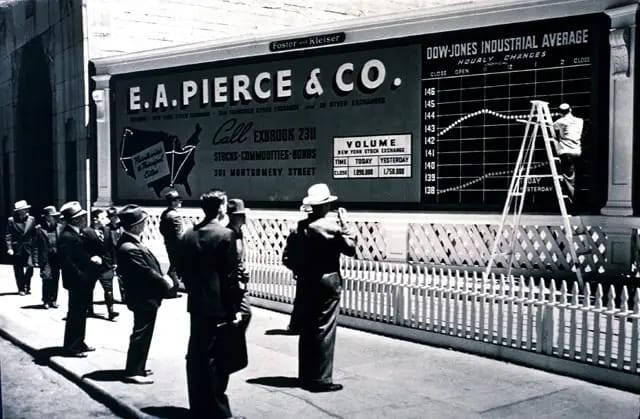

The full book can be browsed here on Flickr and, in an article discussing the collaboration, Ariel S. Winter shares a little of Jack Conroy's no-background: "Jack Conroy (1898-1990) was the first worker-writer (a practitioner of socialist realism) in the United States. He grew up in a coal mining camp in Missouri during the early years of unionization, and went to work in the railroad shops nearby at age thirteen. His initial success as a writer came when H.L. Mencken published his work in the American Mercury. Conroy later returned the favor to many young writers as the founder and editor-in-chief of the socialist literary magazine The Anvil where he published Langston Hughes (another chance meeting!), Richard Wright, Nelson Algren, and Erskine Caldwell." — Ariel S. Winter at We Too Were Children, Mr. Barrie Almost 45 years later, in 1990, John Sandford's Slappy Hooper: The World's Greatest Sign Painter was published by Warner Juvenile Books, a Time Warner Inc. company. Once again, the original legend provided the foundation for Sandford's own storytelling and creativity.  Slappy Hooper: The World's Greatest Sign Painter by John Sandford. Sandford spent some time working for a Chicago sign shop, which was where he learned of the Slappy Hooper legend. In email correspondence, he wrote: "My knowledge about Slappy came directly from experience working for a sign company in the early 1970s; a union job. When I was in art school, the money dried up, and I had to take a year off to make tuition. I got a job as a pictorial artist at Foster & Kleiser billboards, here on Chicago's south side, in an industrial park built where the old Union Stockyards were once located.  Sign painting the Dow Jones Industrial Average on a Foster & Kleiser billboard. "My coworkers talked about Slappy, and I thought he was real! They tipped their hands when they told about his hanging from the middle of the sign, painting as he swung back and forth—like windshield wipers on a car. I finally realized Slappy was a tall tale. I was a little disappointed, but the stories were endless! "I put a lot into the book, basing Slappy's look on a couple friends, and the dedication is to my foreman at Foster & Kleiser. It's all loaded with personal references everywhere; I try to do that with my work (children's books). "The sign painting experience, procedures, working with enamels, oil paint, dryers, extenders, linseed oil, etc, put me years ahead of others when I returned to school. What I believed was a low point in my life, was actually a great blessing—working with long-time professionals was a masterclass, and I wouldn't be me without this." — John Sandford

In the BLAG shop, you can find some copies of The Legend of Slappy Hooper by Aaron Shepard and Toni Goffe. This is the softcover version of their 30th anniversary edition.

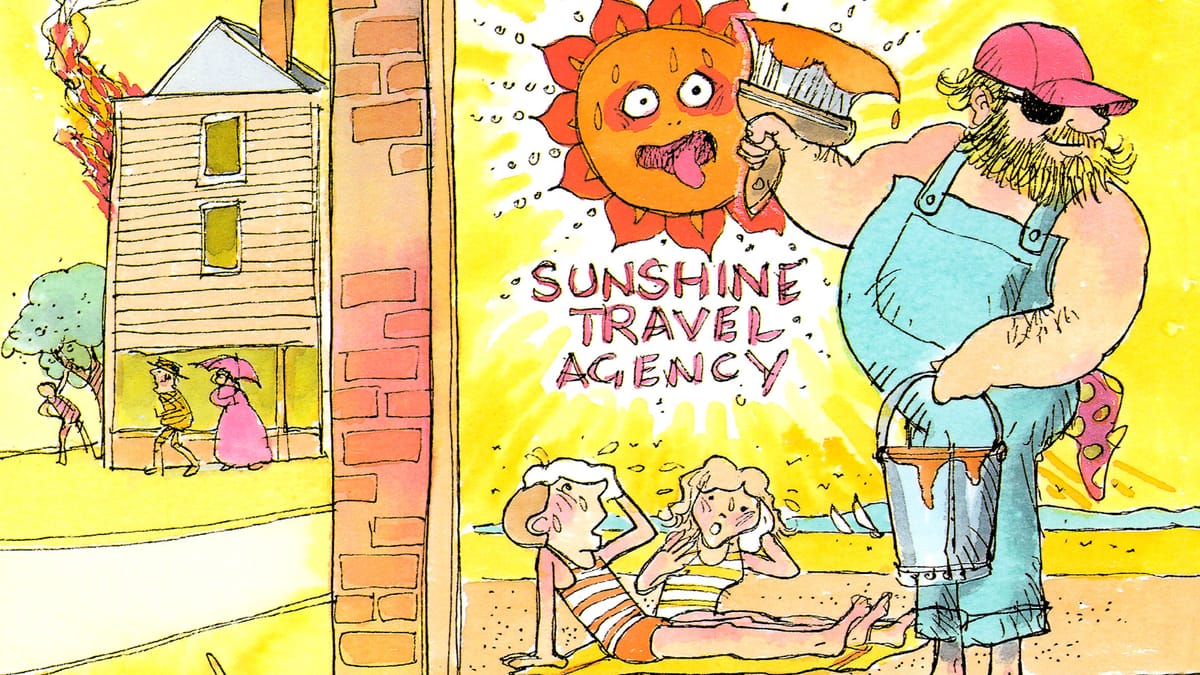

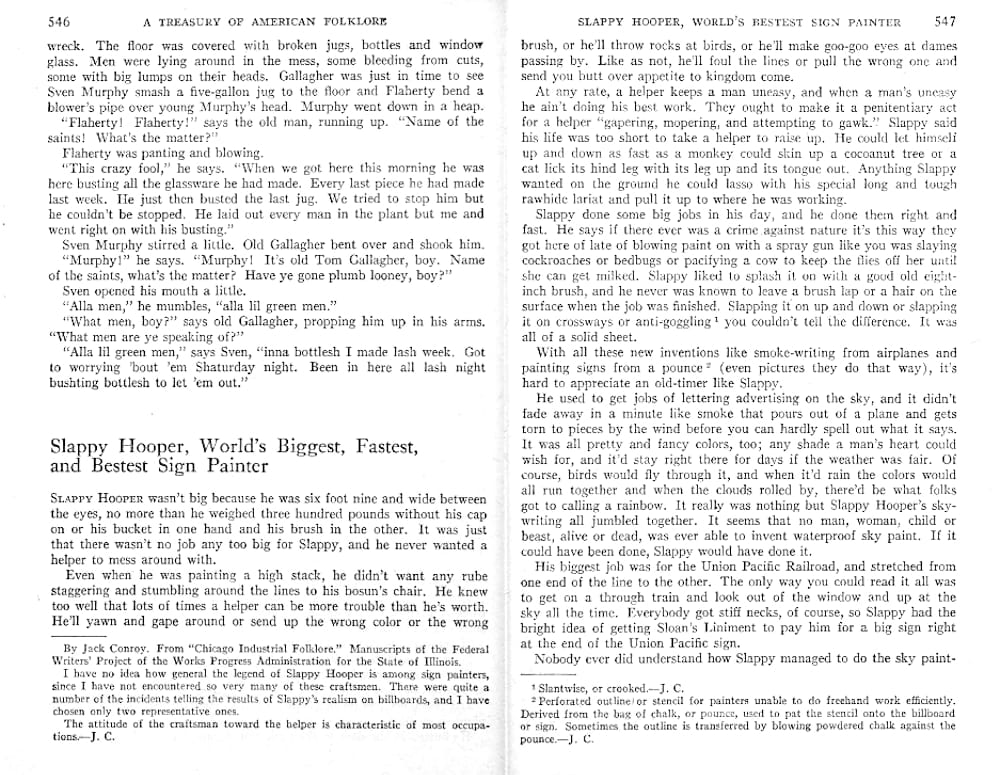

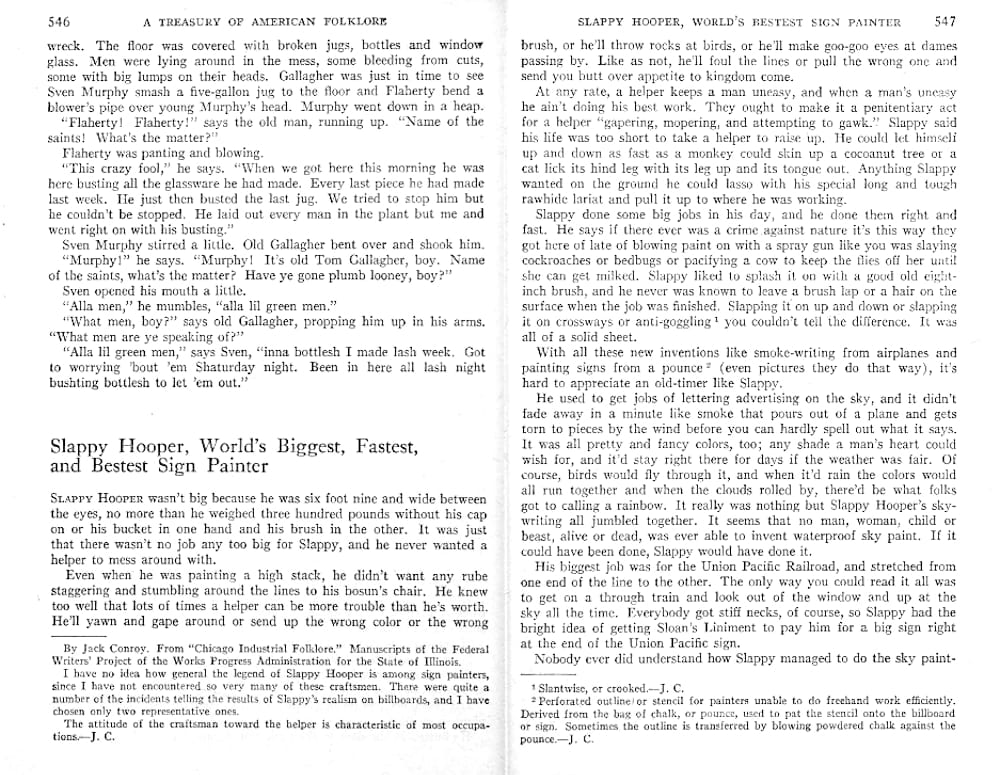

Slappy Hooper, World's Biggest, Fastest, and Bestest Sign PainterAnd here is Jack Conroy's telling of the original legend, as transcribed from B.A. Botkin's A Treasury of American Folklore.  Opening spread from the Slappy Hooper legend in A Treasury of American Folklore by B.A. Botkin. Slappy Hooper wasn't big because he was six foot nine and wide between the eyes, no more than he weighed three hundred pounds without his cap on or his bucket in one hand and his brush in the other. It was just that there wasn't no job any too big for Slappy, and he never wanted a helper to mess around with. Even when he was painting a high stack, he didn't want any rube staggering and stumbling around the lines to his bosun's chair. He knew too well that lots of times a helper can be more trouble than he's worth. He'll yawn and gape around or send up the wrong color or the wrong brush, or he'll throw rocks at birds, or he'll make goo-goo eyes at dames passing by. Like as not, he'll foul the lines or pull the wrong one and send you butt over appetite to kingdom come. At any rate, a helper keeps a man uneasy, and when a man's uneasy he ain't doing his best work. They ought to make it a penitentiary act for a helper "gapering, mopering, and attempting to gawk." Slappy said his life was too short to take a helper to raise up. He could let himself up and down as fast as a monkey could skin up a cocoanut tree or a cat lick its hind leg with its leg up and its tongue out. Anything Slappy wanted on the ground he could lasso with his special long and tough rawhide lariat and pull it up to where he was working. Slappy done some big jobs in his day, and he done them right and fast. He says if there ever was a crime against nature it's this way they got here of late of blowing paint on with a spray gun like you was slaying cockroaches or bedbugs or pacifying a cow to keep the flies off her until she can get milked. Slappy liked to splash it on with a good old eight-inch brush, and he never was known to leave a brush lap or a hair on the surface when the job was finished. Slapping it on up and down or slapping it on crossways or anti-goggling I you couldn't tell the difference. It was all of a solid sheet. With all these new inventions like smoke-writing from airplanes and painting signs from a pounce (even pictures they do that way), it's hard to appreciate an old-timer like Slappy. He used to get jobs of lettering advertising on the sky, and it didn't fade away in a minute like smoke that pours out of a plane and gets torn to pieces by the wind before you can hardly spell out what it says. It was all pretty and fancy colors, too; any shade a man's heart could wish for, and it'd stay right there for days if the weather was fair. Of course, birds would fly through it, and when it'd rain the colors would all run together and when the clouds rolled by, there'd be what folks got to calling a rainbow. It really was nothing but Slappy Hooper's skywriting all jumbled together. It seems that no man, woman, child or beast, alive or dead, was ever able to invent waterproof sky paint. If it could have been done, Slappy would have done it. His biggest job was for the Union Pacific Railroad, and stretched from one end of the line to the other. The only way you could read it all was to get on a through train and look out of the window and up at the sky all the time. Everybody got stiff necks, of course, so Slappy had the bright idea of getting Sloan's Liniment to pay him for a big sign right at the end of the Union Pacific sign. Nobody ever did understand how Slappy managed to do the sky painting. He'd have been a chump to tell anybody. He always used to say when people asked him: "That's for me to know and you to find out," or, "If '`told you that, you'd know as much as I do." The only thing people was sure of was that he used sky hooks to hold up the scaffold. He used a long scaffold instead of the bosun's chair he used when he was painting smokestacks or church steeples. When he started in to fasten his skyhooks, he'd rent a thousand acre field and rope it off with barbed wire charged with electricity. He never let a living soul inside, but you could hear booming sounds like war times and some folks figured he was firing his skyhooks out of a cannon and that they fastened on a cloud or some place too high for mortal eyes to see or mortal minds to know about. Anyways, after a while—if you took a spy glass—you could see Slappy's long scaffold raising up, up, up in the air and Slappy about as big as a spider squatting on it. But that played out, somehow. It wasn't that people didn't like his skypainting any more, but the airplanes got to buzzing around as thick as flies around a molasses barrel and they was always fouling or cutting Slappy's lines, and he was always afraid one would run smack into him and dump over his scaffold and spill his paint if nothing worse. Besides, he said, if advertisers was dumb enough to let a farting airplane take the place of an artist, the more he'd fool them, and it wasn't no skin off his behind. He could always wangle three squares a day and a pad at night by putting signs on windows for shopkeepers if he had to. If I can stay off public works, I'll be satisfied, he thought to himself. So Slappy said to hell with the big jobs. I’ll just start painting smaller signs, but I'll make them so real and true to life that I can still be the fastest and bestest sign painter in the world, if I ain't the biggest any more. It's pure foolishness for a man to try to match himself against an airplane at making big signs. He knew he could do it with one hand tied behind and both eyes punched out. Some sign painters couldn't dot the letter "i" without a pounce to go by. It was enough to make a dog laugh to see some poor scissorsbills wrastling around with a pounce, covered all over with chalk wet by sweat until they looked like a plaster of Paris statue. Then, like as not, they'd get a pounce too small for the wall or billboard they was working on. When it was all on there was a lot of blank space left over. The boss'd yell: "Well, well, Bright Eyes! Guess the only thing to do is fetch a letter stretcher!" If the pounce happened to be too big, it was every bit as bad. "A fine job, Michael Angelo," the boss'd holler, "except you'll have to mix the paint with alum so's it'll shrink enough that we can squeeze it in with a crowbar." One of Slappy's first jobs after he took to billboard painting was a picture of a loaf of bread for a bakery. It would make you hungry just to look at it. That was the trouble. The birds begin to flying on it to peck at it, and either they'd break their bills and starve to death because they didn't have anything left to peck with, or they'd just sit there perched on the top of the billboard trying to figure out what was the matter until they'd just keel over. Some of them'd break their necks when they dashed against the loaf, and others'd try to light on it and slip and break their necks on the ground. Either way, it was death on birds. The humane societies complained so much and so hard that Slappy had to paint the loaf out, and just leave the lettering. He didn't like this a bit, though, because, as he often said, any monkey who can stand on his hind legs and hold anything in his fingers can make letters. The loaf of bread business sort of gave Slappy a black eye. People was afraid to hire him. Finally the Jimdandy Hot Blast Stove and Range Company hired him to do a sign for their newest model, showing a fire going good inside, the jacket cherry red, and heat pouring off in ever which direction. In some ways it was the best job Slappy ever done. The dandelions and weeds popped right out of the ground on the little plot between the billboard and the sidewalk, and in middle January of the coldest winter ever recorded by the Weather Bureau. It was when the bums started making the place a hangout that the citizens and storekeepers of the neighborhood put in a kick. The hoboes drove a nail into the billboard so they could hang kettles and cans against the side of the heater and boiled their shave or boilup water. They pestered everybody in the neighborhood for meat and vegetables to make mulligan stews. They found it more comfortable on the ground than in any flophouse in the city, so they slept there, too. They ganged up on the sidewalk so that you couldn't push through, even to deliver the United States mails. Mothers was afraid to send their little children to school or to the grocery store. The company decided to hire a special watchman to shoo hoboes away, but this was a terrible expense. Not only that, but the watchman would get drowsy from the warmth, and no sooner did he let out a snore than the bums would come creeping back like old home week. Finally, the Company got the idea of having Slappy make the stove a lot hotter to drive the bums clean away. So he did. He changed the stove from a cherry red to a white hot, and made the heat waves a lot thicker. This drove the bums across the street, but it also blistered the paint off all the automobiles parked at the curb. Then one day the frame building across the way began to smoke and then to blaze. The insurance company told the Jimdandy Hot Blast Stove and Range Company to jerk that billboard down and be quick about it, or they'd go to law. Slappy says now he feels like locking up his keister and throwing away the key. They don't want big sign painting and they don't want true-to-life sign painting, and he has to do one or the other or both or nothing at all.

Provided by Jack Conway. - 'Anti-goggling': Slantwise, or crooked.

- 'Pounce': Perforated outlines or stencil for painters unable to do freehand work efficiently. Derived from the bag of chalk, or pounce, used to pat the stencil onto the billboard or sign. Sometimes the outline is transferred by blowing powdered chalk against the pounce.

- 'Public works': It is the pride of many independent craftsmen and boomers that they have never been chained to a job on "public works," i.e., in a large factory where a time clock is punched and the routine is deadening. To the freelancing artisans, going on "public works" is a fate worse than death.

- 'Boilup': Boiling of clothing to kill body lice.

- 'Keister': Satchel, resembling a rigid suitcase, in which itinerant sign painters keep their work materials and often their clothing as well.

"From 'Chicago Industrial Folklore.' Manuscripts of the Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration for the State of Illinois. "I have no idea how general the legend of Slappy Hooper is among sign painters, since I have not encountered so very many of these craftsmen. There were quite a number of the incidents telling the results of Slappy's realism on billboards, and I have chosen only two representative ones. "The attitude of the craftsman toward the helper is characteristic of most occupations." — Jack Conroy Thank you to Aaron Shepard and John Sandford for their collaboration in researching and sharing the legend of Slappy Hooper. Now go tell the story to the kids in your life!

More BooksMore History

|