Net Interest - The Biggest Investor in the World

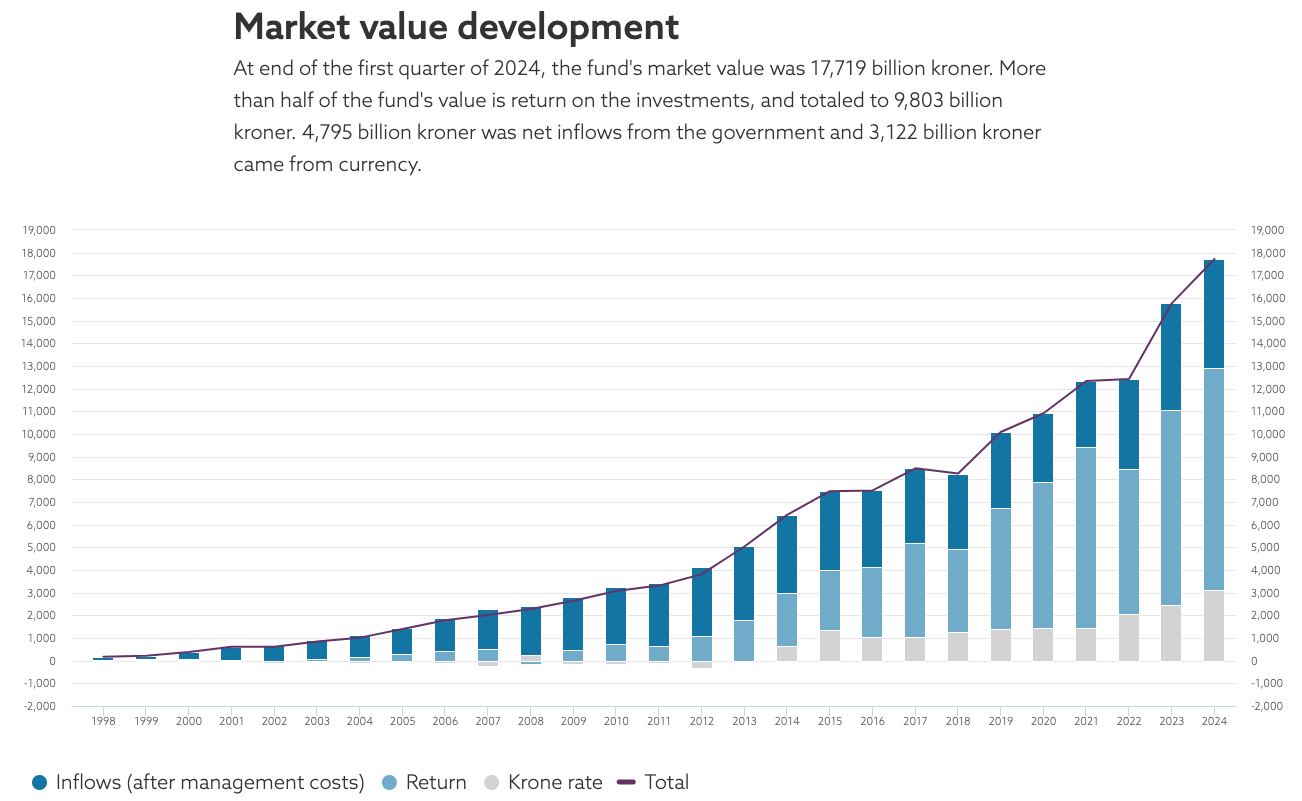

Annie Duke is a poker champion and decision-making expert. Her 2018 book, Thinking in Bets, draws on her card-playing experience to explore how people can make smarter decisions when the facts are not all available. Recommended by leading investors such as Marc Andreessen and Howard Marks, it is widely read in the investment community, where decision-making in an environment of uncertainty is core to the job. This week, Annie spoke at the annual Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM) conference in Oslo (she beamed in via Zoom). As the largest single owner of the world’s stock markets, NBIM holds considerable sway, and each year it gathers experts in a range of fields to discuss a topic – this year: How to become a better investor. NBIM already has a strong track record. It has outperformed its benchmark across its 26 year history and now sits on $1.6 trillion of assets. But there is always scope to do better, hence the conference. Andreessen and Marks were both there; also Adam Grant, Michael Mauboussin and Marc Rowan. Annie Duke presented the topic of her latest book, Quit: The Power of Knowing When to Walk Away. From an investment perspective, knowing when to quit can be a powerful skill. Annie highlighted a recent research paper that shows that closing positions too late creates a material drag on investors’ performance. “While expert investors are alpha generators when putting risk on, they give alpha back on their exit decisions,” she told attendees.¹ From an organizational perspective, though, quitting can be hard. Indeed, NBIM’s very origin story is tied up in one company not quitting. That company was Phillips Petroleum and it follows a long tradition of companies in the oil industry giving it one more go… In 1859, “Colonel” Edwin Drake was about to run out of money. He’d been drilling for over a year in Titusville, Pennsylvania and, one by one, his financial sponsors had given up hope. Finally, his last remaining backer sent him an order, instructing him to pay his bills, close up the operation and return home. Before the message arrived, Drake struck oil. The American oil industry was born. A similar story unfolded in Persia almost half a century later. George Reynolds was chief engineer on the ground, working for Burmah Oil, whose Scotland-based executives had become unhappy about his slow progress. After seeing nothing from Reynolds in over six years, they dispatched a letter, telling him that if no oil was found at 1,600 feet at the two wells he was drilling at Masjid-i-Suleiman, he should “abandon operations, close down, and bring as much of the plant as is possible down to Mohammerah.” In May 1908, the letter in transit, first one and then the other well began to gush. Reynolds fired off a cable to head office: “The instructions you say you are sending me may be modified by the fact that oil has been struck, so on receipt of them I can hardly act on them.” Starting in 1920, Europeans began searching for oil closer to home. The Suez crisis of 1956 gave the hunt more urgency and, in 1959, a large gas field was discovered at Groningen in the Netherlands. Realizing that the geology of the North Sea matched that of Holland, oil companies began to explore in adjacent waters. One man whose interest was piqued was the vice-chairman of Phillips Petroleum of Oklahoma, who noticed a drilling derrick near Groningen while on vacation in the Netherlands in 1962. He returned with colleagues and, in 1964, they started drilling. After five years, they hadn’t found anything. In total, Phillips and other oil companies drilled 32 wells on the Norwegian continental shelf – they all came up dry. The process was expensive and eventually the message came from Oklahoma: “Don’t drill any more wells.” In November 1969, Phillips gave it one more go – reportedly because it had already paid for the use of a rig, the Ocean Viking, and couldn’t find anyone else to sublease it. That last drill proved a success: from 10,000 feet beneath the seabed, it drew oil. Daniel Yergin tells the story in his definitive history of the oil industry, The Prize. He says that a few months after the find, a senior Phillips executive was asked at a technical meeting in London what methods Phillips had used to diagnose the geology of the field. “Luck,” came the reply. The Ekofisk oil field Phillips had discovered turned out to be huge, originally estimated to contain more than 3 billion barrels of recoverable oil. Production started in 1971 but it wasn’t until oil prices rose dramatically during the 1973 oil crisis that its true value became apparent. By then, other fields had also been discovered and the Norwegian government was keen to retain some of the value. As well as participating directly, in 1975, it introduced a special tax on top of already high corporate tax rates to capture 78% of producer profits. Initially, those tax receipts were funneled into the government budget. But a commission set up in 1983 warned that variations from changes in oil prices should not be allowed to impact directly on government expenditure. The commission proposed a “buffer fund” to absorb revenue fluctuations and uncouple production activity from spending decisions. The idea was ready to go when an oil price collapse in 1986 made it moot. Saudi Arabia abandoned its policy of cutting production in response to increasing output elsewhere and prices fell, shattering Norwegian government hopes to accumulate financial reserves. When the idea was reprised in 1990, there wasn’t any wealth to invest but, as a tool to make the country’s use of oil revenue more transparent, a fund was nevertheless established. For five years it sat there – an “exercise in accounting” – as the country’s non-oil deficit (exacerbated by a banking crisis, no less) continued to exceed annual net oil and gas revenue. Finally, in May 1996, the finance minister was able to make his first transfer to the fund, of close to 2 billion kroner ($300 million). Later that year, another 45 billion kroner was added ($7 billion). The fund is now worth 17,395 billion kroner, equivalent to $1.6 trillion, or 3x Norway’s GDP. Money has been added along the way, but less has been taken out, and investment performance has contributed to the fund’s growth. The government maintains a strict spending rule that allows it to withdraw only the equivalent of the real return on the fund – estimated to be around 3% per year – but 3% of a big number is a big number and such withdrawals are sufficient to fund 20% of the state budget. Meanwhile, the fund compounds. Net flows account for less than half the current value of the fund; most is due to investment performance.² This week’s investment conference highlighted some of the challenges the fund now faces. Is it too big? Is its mandate to invest principally in public securities appropriate? As a government-owned entity, can it compete with private players? Annie Duke delivered her presentation in the section about behavioral characteristics of the best investors, not the one on building successful investment organizations, but the question of whether the fund should quit its current strategy is worth asking. To join me behind the scenes inside the world’s biggest investor, read on... Subscribe to Net Interest to read the rest.Become a paying subscriber of Net Interest to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content. A subscription gets you:

|

Older messages

Decisions Nobody Made

Friday, April 19, 2024

Dan Davies Introduces His New Book. Plus: Earnings Season! ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Alpha Capture

Saturday, April 13, 2024

The Art of Portfolio Construction ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Escaping a Value Trap

Friday, April 5, 2024

European Banks Through the Eyes of Their Longest-Serving Analyst ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Private Payments

Friday, March 22, 2024

Nuvei's Time as a Listed Company May Be Coming to an End: Was It Worth It? ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

The Last Challenger

Friday, March 15, 2024

Richard Branson vs. The Big Four ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

You Might Also Like

Longreads + Open Thread

Saturday, March 8, 2025

Personal Essays, Lies, Popes, GPT-4.5, Banks, Buy-and-Hold, Advanced Portfolio Management, Trade, Karp Longreads + Open Thread By Byrne Hobart • 8 Mar 2025 View in browser View in browser Longreads

💸 A $24 billion grocery haul

Friday, March 7, 2025

Walgreens landed in a shopping basket, crypto investors felt pranked by the president, and a burger made of skin | Finimize Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March 8th in 3:11 minutes.

The financial toll of a divorce can be devastating

Friday, March 7, 2025

Here are some options to get back on track ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Too Big To Fail?

Friday, March 7, 2025

Revisiting Millennium and Multi-Manager Hedge Funds ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

The tell-tale signs the crash of a lifetime is near

Friday, March 7, 2025

Message from Harry Dent ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

👀 DeepSeek 2.0

Thursday, March 6, 2025

Alibaba's AI competitor, Europe's rate cut, and loads of instant noodles | Finimize TOGETHER WITH Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March 7th in 3:07 minutes. Investors rewarded

Crypto Politics: Strategy or Play? - Issue #515

Thursday, March 6, 2025

FTW Crypto: Trump's crypto plan fuels market surges—is it real policy or just strategy? Decentralization may be the only way forward. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

What can 40 years of data on vacancy advertising costs tell us about labour market equilibrium?

Thursday, March 6, 2025

Michal Stelmach, James Kensett and Philip Schnattinger Economists frequently use the vacancies to unemployment (V/U) ratio to measure labour market tightness. Analysis of the labour market during the

🇺🇸 Make America rich again

Wednesday, March 5, 2025

The US president stood by tariffs, China revealed ambitious plans, and the startup fighting fast fashion's ugly side | Finimize TOGETHER WITH Hi Reader, here's what you need to know for March

Are you prepared for Social Security’s uncertain future?

Wednesday, March 5, 2025

Investing in gold with AHG could help stabilize your retirement ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏