[Original post here - Prison And Crime: Much More Than You Wanted To Know]

Table of Contents:

1: Comments On Criminal Psychology

2: Comments On Policing

3: Comments On El Salvador

4: Comments On Probation

5: Comments That Say My Analysis Forgot Something

6: Comments With Proposed Solutions / Crazy Schemes

7: Other Comments

Jude (blog) writes:

This . . . matches my experience working with some low-income boys as a volunteer. It took me too long to realize how terrible they were at time-discounting and weighing risk. Where I was saying: "this will only hurt a LITTLE but that might RUIN your life," they heard: "this WILL hurt a little but that MIGHT ruin your life." And "will" beats "might" every time. One frustrating kid I dealt with drove without a license (after losing it) several times and drove a little drunk occasionally, despite my warnings that he would get himself in a lot of trouble. He wasn't caught and proudly told me that I was wrong: nothing bad happened, whereas something bad definitely would have happened if he didn't get home after X party. Surprise surprise: two years later he's in jail after drunk driving and having multiple violations of driving without a license.

The “proudly told me that I was wrong - nothing bad happened” reminds me of the Generalized Anti-Caution Argument - “you said we should worry about AI, but then we invented a new generation of large language model, and nothing bad happened!” Sometimes I think the difference between smart people and dumb people is that dumb people make stupid mistakes in Near Mode, and smart people only make them in Far Mode - the smarter you are, the more abstract you go before making the same dumb mistake.

Blackshoe writes:

Putting this in as nice and polite a way as I can: I suspect I am on the low-end for IQ (perfectly high midwit-ish 117) of the average ACX reader, but interestingly wife (135+ish, based off ACT score, STEM PhD from Ivy League uni) is closer to modal for this site. So I get to have the fun experience of interacting with someone a full StDev smarter than me, and one thing I often experience is that smart people tend to underestimate how much harder it is for someone with that difference in raw intellectual capacity to do things they can ("No, love of my life, I am not interested in making a Python model to figure out which healthcare option is the best for us."). This was especially heightened when we were foster parents for awhile, and one of our placement was...whatever the appropriate term is nowadays for someone with a 63 IQ (which we were probably the first people in his family to find out about, since I was told I was the first person to ever show up for one of his school's IEP meetings); living with top and bottom 1% intellectual functioning was a very illustrative experience!

IMHO, a major problem with discussion about crafting programs for effective deterrence is that (especially for violent crimes-Jason Manning's review of Fragging notes how Wolfgang noted the modal murder starts with a very trivial dispute) the people who mostly need to be deterred are frankly too stupid for that to work (executive planning and IQ are decently correlated and breaks down rapidly below a certain threshold, which is higher than the cutoff for legal disability) and the people crafting these program won't get that the processes aren't likely to work with the population they are trying to fix because that population is too different in mental functioning to pay off. Our friend Joe from the Open Thread my intellectually get that he shouldn't murder someone for repeatedly taking fries off his plate (actual case Manning notes) and that he will be punished if he does so, but it will be very hard for that intellectual knowledge to kick in before he has killed the fry taker.

So incapacitation may have more value (especially, as mentioned in the comments, the age factor of incapacitation: the value of keeping people in jail in their criminally-prime years).

I also have a more mathematically-inclined wife - it’s a tough but rewarding extreme lifestyle.

Deiseach writes:

"Take a moment to imagine how your own life would change if you spent ten years in prison. Seriously, spend a literal few seconds thinking about your specific, personal life."

The problem is, some/many/lots of the people going to jail don't have spouses, jobs, etc. in the first place. Ten years in jail and then coming out to all the consequences afterwards is their life *already*, after six months in jail/multiple 'second chances' every time they came up before the court.

I've mentioned this one example before from my personal experience over my work life, but I'll repeat it once again: a girl that I first encountered as an early school leaver, and because she was engaging with various services that I coincidentally happened to work for, I could track her career over the years.

So she went from vulnerable teenager with disrupted home life, to dropping out of school, to not engaging with the support services for early school leavers, to what used to be called taking up with a bad crowd, but that's probably a disfavoured term nowadays because it's discriminatory and judgemental of persons with societal difficulties (aka being petty scumbags), to (of course) weed and other 'soft' drugs to picking up a heroin habit. Along the way she had a kid with, of course, no husband and the boyfriend flitted in and flitted out.

End result, she stabbed another young woman in the stomach at a house party (drugs and drink present, of course) and ended up with a prison sentence while her mother took care of the child.

She never *had* the "my ordinary normal life of a job and family and the rest of it will be disrupted by going to jail!" In fact, I think prison probably was *better* for her as it was a chance to break those exact connections that were dragging her down, and letting her get sober and clean and maybe, who knows, a miracle, getting her head together and getting skills and help for post-prison life.

There are other people who die early and I see the names in the local paper and I go "Oh yeah" because again, I know the background, and I'm not surprised because this is all the inevitable ending to the life they lived.

I've encountered some of the early school leavers on the programme for such, and I've forecast even at that age (late teens) they're gonna end up in jail, because the little idiots don't give a flying fuck about learning any kinds of skills leading to getting a job and a normal life. That's for the squares and the fools, they want weed, easy money, and free time. They're on the path to petty crime if not already started on it, and one day they'll go too far and either end up stabbed by a bigger, badder criminal or they'll finally run out of "second chances" and have to do time.

And it'll be the best place for them, because they *will* be off the streets and not interfering with ordinary people. They're not interested in rehab even in or after coming out of jail, they'll fall back into the same old lifestyle because all they are interested in is drugs, easy money, and free time, and six months or ten years is all the same.

Re: the shoplifting, I think *all* the commentators are right; Graham about the view of the cops on the ground, Andrew about the "scared straight" but I imagine that for first time offenders or people just starting on the petty crime path, and CJW for how the sausage is made in the courts and legal systems.

I have also worked with some future criminals (and a few current criminals). My impression is that many are doomed from birth, but some are in a gray area where they could potentially go either way depending on things like availability of drugs, availability of drug treatment, someone holding their hand to help them land a job, etc.

According to BJS and this fact sheet: 60% of prisoners had a job in the 30 days before their crime, and 50% were working full-time. 40% had ever married, and 15% - 25% were currently married (though I can’t tell if that’s at time of crime, or at time of survey in prison). About half had children, and 40% of fathers lived with their children at the time of the crime.

I think this matches my picture of “most don’t have very stable lives, but some do, and most have something.”

CJW writes:

Given my extensive years in crimlaw, I have a lot of thoughts about this. A recurring problem with discourse in this area is that the practical realities involve an intersection point between criminals (a highly irrational subculture) and bureaucrats (a class of people who are given idealistic speeches at conferences and then go back to a job where there's bizarre incentives to say 2+2=5 if it clears their desk briefly). So not only are the decisions of the actors irrational and arbitrary, even identifying WHAT happened is inscrutable to people who don't practice crimlaw. I don't have time to react to everything here, but just a few points on the non-linearity of how criminals see sentences.

"So most deterrence will look more like the Proposition 36 proposal we discussed last month, which increases shoplifting sentences from six months to three years. If we use H&T’s numbers (probably inappropriate since there may be nonlinear effects), we would expect that section of Prop 36 to deter crime by 2%."

Correct about the expected nonlinear effect. I believe the Proposition would be ineffective because practical constraints would force prosecutors to amend charges rather than seek the heightened sentences required. But if somehow the sentences actually came to pass, the criminal class sees this VERY differently. A misdemeanor with a 6 month jail max probably means that at worst you get arrested, are held in some county facility, can't post bond, your lawyer screws around with discovery and motions to make themselves feel like they did something, and then you plead out to time served at some point. A 3 year sentence isn't just about the duration, it has to be served in a prison, which is a very different world than county jail.

Many lower-level criminals who will happily sit in jail for 6 months would push back strongly at having to enter the prison system even if you told them to expect parole at the same 6 month mark. Whether or not it deters the crime, it certainly deters pleading guilty as charged and greatly increases the chance of the defendant snap-accepting any misdemeanor plea bargain offer. Jail vs prison punishments are different in kind, not merely in duration. (There are large metros with jails that behave more like prisons with stable inmate populations serving sentences, as opposed to keeping "sentenced to jail" and "awaiting trial, couldn't post bail" people together, but as the "sentenced" group would be mostly low-level offenders and the "awaiting trial" group would have included more serious offenders, I wouldn't be surprised if these facilities were actually preferable to ordinary jail.) [...]

There are also threshold points even along a spectrum of years that are given irrational weight during plea negotiations. Numerous repeat offenders in my state were far more likely to accept a deal of 7 yrs than 8, this break point was consistently noted in negotiations. The only explanation we had was that historically C felonies maxed out at 7 and were treated more leniently by parole board than A/B felonies-- but if you had committed a B felony and were subject to the higher range, then the difference between 7 and 8 was no different than the difference between 8 and 9, getting 7 didn't make them treat you as if you were a lower class offender. But they acted as if it mattered to them greatly.

Sifrca writes:

I’m a public defender in a “tough-on-crime” state. My experience has been this:

1. “Deterrence” via longer sentences is a meme. Criminals don’t really give a shit about the length of the sentences they might face. Many of them don’t even know what the length is until they’re arrested and headed to plea negotiations. Kind of hard for the length of the punishment to be a deterrent if the criminal doesn’t even know what it is until after he acts.

Most crimes occur because the criminal either acts:

(a) impulsively (doing something in the moment without any consideration to long-term consequences - stereotypical example: kid shoplifts because his buddies dare him to),

(b) compulsively (they are generally aware of the risks of getting caught, but have some other mental hangup preventing that from factoring in their decisionmaking - stereotypical example: pathological shoplifter), or

(c) arrogantly (they know the risks but believe they simply won’t get caught - stereotypical example: a “professional” shoplifter like your 327 in NYC)

All of these mental models are inelastic with respect to the punishment. They are, however, highly elastic with respect to surveillance and the physical presence of police. Impulsive criminals may be deterred by the presence of surveillance and police alone; “arrogant” criminals and the more daring impulsive criminals will be humbled by being caught and become more cautious, if not abandon their enterprises; and those who remain undeterred by the threat will be deterred by the followthrough.

I think this is true regardless of the severity of the crime, which dovetails with your overall conclusion that prison is less cost-effective. The flip side is that prison time (theoretically) guarantees no reoffense, whereas other methods can fail, and we’re willing to pay a higher premium for the certainty with more serious offenses.

2. Your marginal reflection is spot-on because we punish different crimes very differently, which means that not all additional years are created equal. Say that the mandatory minimum for rape is 20 years, and it’s political suicide to try to lower that minimum. If a rapist is guaranteed to get at least 20 years in prison, then on the margins, making the sentences any longer should have next to zero additional negative aftereffect (there probably will BE significant negative aftereffects already, but they’re “baked in” to the 20-yr minimum; the marginal increase is likely small because the damage is already done), but it probably has some considerable positive incapacitation effects (most sexual predators have compulsion issues that are difficult to “cure,” or else simply don’t believe they’ll be caught next time, or both). So on the margins, increasing the sentence of rape could be beneficial.

Meanwhile, shoplifting is never seriously going to carry a 10+ yr sentence, so the cost of adding a year is considerable. There, the aftereffect issue is substantially larger.

3. Related to those points, I suspect an important part of the analysis is understanding the cost of different types of crimes. I’m not even sure how one would put a “price” on the harm caused by rape, for instance, but we evidently value it much more than the $34,000 average social cost of a crime, because the punishment for rape is substantially higher than the punishment for the average crime. The higher the cost of a crime, the comparatively more valuable incapacitation through prison can be.

Jude again:

I moved for a while to a central European country and was impressed with the criminal justice system and the low level of crime/high level of compliance, despite the high amount of migration. The biggest thing I noticed is the certainty of being caught that you mentioned. Sentences were (to my American eyes) relatively short and weak - and more liberal Americans often thought there was less crime because the country was somehow more humane. But the main thing I noticed was: the certainty of being caught was high. Police were everywhere and very responsive. Small fin3es and one-night-in-jail punishments were everywhere for petty crimes. I think the U.S. would benefit from strong policing with simple, consistent punishments for many small crimes, especially for first time offenders.

I was curious whether the country really had more police or just a more law-abiding culture, but Richard Gadsen has statistics:

The US has far fewer cops than most European countries per capita.

The US has about 242 / 100k (FBI figures, 2019)

Just picking a few examples, Belgium has 334, Germany 349, Hungary 367, France 422, Italy 456, Spain 534

The European jurisdictions that are lower than the US are: England-and-Wales, Sweden, Iceland, Denmark and Norway.

Marian Kechlibar offers a caution:

These comparisons are somewhat strained, given that in some European countries, "cops" include people who never leave their office and perform some sort of administrative duty that in other countries isn't performed by police at all.

For example, issuing various permits.

Czechia is notorious for having a large amount of cops nominally, but relatively few beat cops. Most of the difference are bureaucrats formally employed by police.

I would be curious to learn whether European countries really do have more street cops than the US, and, if so, why (given that the US has more crime). The data is from 2019, before the wave of “defund the police”, so that can’t be it.

Performative Bafflement (blog) writes:

American police spend approximately all police-hours on traffic tickets, rather than solving actual crimes. And this is with homicide closure rates of ~50% and rape ~30% and property crimes ~10%.

It's a bit of math to get there, but my full argument is here:

I’ve had to rederive these points so many times now, I’m just making a permanent post I can point people to. Broadly, police dedicate at most 10-20% of their time to “actually solving crime” and dedicate the vast majority of their time to overhead and traffic stops…

a month ago · 1 like · Performative Bafflement

Bottom line, if you want to increase police funding, you need to legislate at a high level that they CANNOT use the extra funds / police-hours for traffic tickets, but instead must use them on solving actual crimes.

Otherwise, we're just going to get more traffic tickets and similarly laughable closure rates of actual crimes.

I’m not an expert but PB’s argument looks sound to me. It also makes sense - he writes “Look at the choices - sit in a nice air conditioned car for 80% of your time, interacting with the soccer moms and nice middle and upper class people you pull over, OR be out in the bad parts of downtown interacting with volatile psychos, shambling fentanyl zombies, and schizophrenic homeless people? Oh, plus writing tickets generates revenue for the city, and doing anything to prevent or investigate actual crime has you interacting with all the psychos and zombies. They are doing easy things because they are easy, and because doing hard things is not only hard in and of itself, but also has much greater reputational risk in our post-Floyd panopticon society.”

So how do we get police to fight crime?

Bram Cohen (blog) writes:

Someone with experience in the field told me there are some dumb problems with hiring cops as well, like requiring everyone who works in law enforcement start as a beat cop, which creates unnecessary disincentives for people who are physically unsuited to working as beat cops or overqualified for the position.

TheAnswerIsAWall writes:

I am a felony prosecutor in a major US metro area—I should probably be prosecuting crimes right now rather than writing this—but I wanted to add […] it is quite correct to hold that the next marginal anti-crime dollar would be better spent on policing than on incarceration. However, that also isn’t an easy solution. Before you can actually do that in a meaningful way, you need to address what has become a generational challenge in much of the country: staffing police departments. The job has always been dangerous and (comparatively) poorly paid. Add in the decline in public esteem for the job—particularly post-George Floyd—and the rate limiting bottleneck to crime reduction in most metropolitan areas has become recruiting enough talented people willing to do that job. We just don’t have enough and you can’t manufacture them with a 5% pay raise or some other token effort.

I have heard this from many people but don’t understand it. Everyone knows there’s a shortage of well-paying blue-collar jobs that don’t require college degrees. Being an officer is respectable (liberals might yell at you, but it confers status in a way that eg retail or construction doesn’t), doesn’t have a lot of prereqs, and has good room for advancement. Why is it so hard to fill these positions? Sure, there’s a lot of bureaucracy and nonsense and dealing with terrible people, but that’s also true of eg teaching, nursing, etc, and those are highly competitive.

Jacob Steel writes:

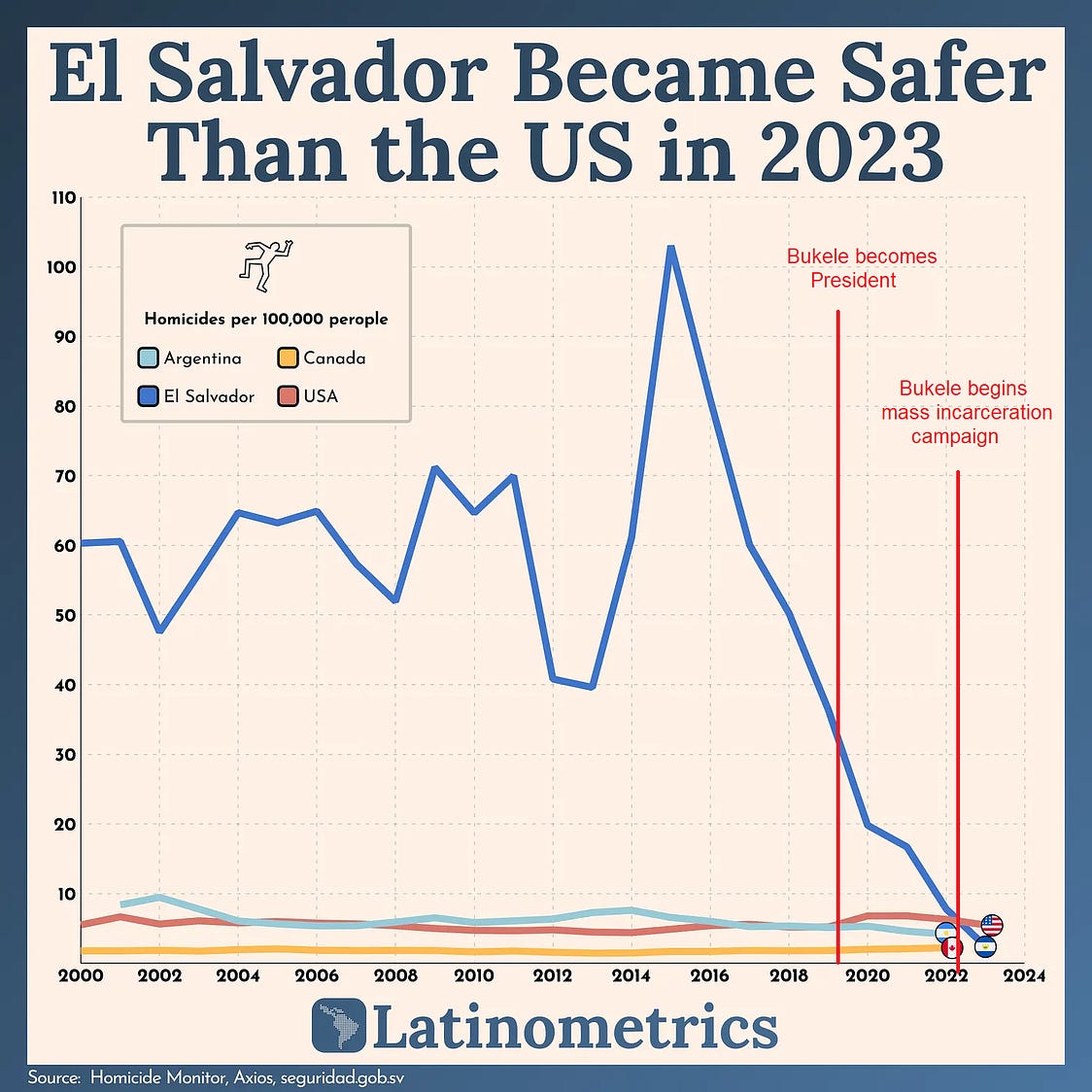

I am deeply sceptical that a significant part of the decline in homicide in El Salvador was due to mass incarceration, unless the flow of time and causation has reversed itself.

That graph of homicides per year you posted has a really sharp peak in 2015, at around 100 per 100,000 people per year. Thereafter, it starts to plummet dramatically every year.

So El Salvador clearly got /something/ right, and that something happened around 2015.

The thing is that mass incarceration in El Salvador started in 2022, by which time the homicide rate had already fallen massively, to about 10 per 100,000, and was still falling rapidly. That improvement didn't accelerate in 2022 - yes, it continued, but if anything it slowed.

So I think this is almost certainly correlation not causation - unless falling homicide in El Salvador somehow caused mass incarceration!

WTF? This appears to be totally true! Here’s the graph from the original post, now with key events marked in red:

How come in one million articles about Bukele and crime in El Salvador, including many trying to discredit him or say it wasn’t worth it, I’ve never heard a peep about this? And if it wasn’t Bukele or mass incarceration that did it, then what was it?

[Y] writes:

I have issues with the El Salvador portion of this post.

These charts show that the Bukele mass incarceration movement only resulted in a massive increase in the prison population from 2020 forward, based on projected population. The graph shows the murder rate peaking in 2015 and dropping precipitously in the next three years prior to Bukele's presidency. This means, unless I'm missing something, that the vast majority of the decrease in the murder rate occurred before Bukele took office and started putting people in prison at all and thus cannot be attributed to his policies, incarceration or otherwise. Bukele took office in 2019 and did not begin the crackdown until June of that year. The state of emergency that allowed the government to suspend various rights in order to crack down on gangs even further didn't begin until early 2022 While the murder rate was obviously still quite high before Bukele's incarceration policies began, it seems almost actively misleading not to mention that it was collapsing even before he instituted these policies as a result of things like a renewed gang truce in 2016 under the previous government and instead seemingly attribute all of it to him.

Further, the post-Bukele homicide data is dubious in several ways. The Bukele government stopped counting bodies discovered buried in unmarked graves as homicides, incentivizing gang members to hide their victims instead of publicly displaying them as trophies or warnings as they had done in years prior. They stopped counting people the police or military shot as homicides, classifying them instead as “legal interventions". They have excluded killings in prisons from the homicide data, which seems like exactly the most obvious way to lie about homicide rates when you begin imprisoning everyone.

https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/08/08/el-salvador-bukele-crime-homicide-prison-gangs/

The source article suggests the above may represent as much as a 47% undercounting. Well, one might say, that still leaves El Salvador much safer than before Bukele’s tenure. But I’m not linking the above to try and pin down exactly the right figure of undercounting. I would suggest instead that these changes to the metrics demonstrate a willful and deliberate pattern of obscuring the homicide rate in El Salvador. The post-Bukele data consequently seems almost useless to me, as you cannot really assume we know all the ways the Bukele government is fudging the data. These are just the ones on record.

It’s not that murder has disappeared in El Salvador - it’s more like it’s now de facto legal in many contexts. An MS13 member who rolls up on a rival gang’s stash house and shoots it up now knows that if they can bury the bodies in an unmarked grave outside of town without being caught red-handed with the shovels and corpses, the victims will legally cease to exist. They’re not prosecuting people for these murders, right? Otherwise they would show up in the data. The media doesn't talk about them. You don't see the evidence. Out of sight, out of mind.

I'm not suggesting no murders were prevented as a result of the Bukele government's mass incarceration policies, obviously. I can also see the argument that it's good for society for criminals to kill each other in prison yard fights instead of getting into shootouts in a marketplace where an innocent bystander also gets their head blown off. I just think the fundamental premise - that he arrested everyone and it caused murders to stop happening and we need to reason forward from there - is extremely dubious.

Drethelin writes:

idk about the statistics but multiple people I talked to in el salvador specifically told me theft was WAY down

like walking down the street with your phone in your hand was now an option where it used to not be

people can now both afford to and feel safe owning cars, etc.

among other things they are very proactive about using what we wouldn't really consider due process, eg cops browsing facebook and like, going after guys that people post from their security camera footage as taking their bike or whatever

Thanks - I had said in the post that although murder was down, the statistics didn’t really show this about theft - but I was eyeballing statistics not really gathered for this purpose and if the news on the ground is that theft is down, I believe it.

In response to a question of why probation with GPS tracking hasn’t taken off as an alternative to prison, Peter answers:

Because convicts turn it down. You see at least in America probation (which is what GPS monitoring is part of) and incarceration aren't related, you get no credit for the former when it comes to the latter and people like to overlook over half of people incarcerated aren't there for any crime at all but simply a technical probation violation like getting fired from your job from not showing up on time because your probation officer randomly changes times of meetings daily (which is also results in prison even if you are one minute late).

If the max sentence is five years prison plus probation time doesn't count and you have a more likely than not chance of violating probation because it's designed to be unreasonable and cause failures as a back door way for judge's to avoid trials, why would you accept GPS monitoring which will only increase your chances of being violated.

I.e..why do nine years (four years probation out of your ten year probation, then violated, then five in more actual prison) when you can just do five. Generally the rule among convicts is if the prison sentence is shorter than the probation sentence, just take prison day one. As a convict you can, and many do, turn down probation.

If you want to fix this then you need to let convicts "try" probation where they get credit at a 1-1, or even better motivate them so let's say 2-1, towards a future prison sentence when they fail. This entire conversation (OP) is worthless as it's making the standard mistake of just looking at prison and not probation, jail, fines, etc all which backdoor as a way to avoid trials lead to prison.

This isn’t very clearly written, but my impression is that Peter is saying that violating probation gives you a longer prison sentence than just accepting prison in the first place, probation is deliberately designed to be near-impossible to keep, and so it’s a con to trick criminals into longer sentences without having to get them through a judge and jury. Criminals know this, so they refuse probation.

This kind of conflicts with the “criminals have high time preference and make terrible decisions” point above, so I’m not sure what to think of it.

I wonder if people ever try GPS tracking (without the rest of probation) as a prison alternative. “You’re getting off with a warning this time, but wear this tracker, and if you commit any other crimes in the future, we’ll know.”

More from Peter:

Remember, the entire point of probation is to get people to avoid a trial by plea dealing to probation and then put them in prison anyways without any due process because reasonable people, the sort that takes plea deals, believe in the system hence overestimate their ability to complete probation. And so you put them in prison on a technical violation, i.e. getting fired after you intentionally caused them to do so, not having a place to live after you intentionally refused to approve anywhere they tried live, changing their appointment times without confirming they know ("I left a message with their dog"), or just harass them until they give up and just go to prison.

Americans tend to discount probation as a joke but any experienced convict knows probation as implemented is worse hence just goes to jail. Also note that probation and PAROLE are different and significantly so, you actually get credit for parole time. Parole WANTS you to succeed, after all they paroled you, probation doesn't.

They aren't even the same group of government offices either which is part of the problem. Probation falls under the judiciary (they work for the court) hence they free up budgets the faster they can move you over to the executive (prison) branch whereas parole is a cost saving measure as it falls under the same prison budget, i.e. parole officers aren't probation officers. Also all those fancy rehabilitation programs people love to tore to decrease recidivism goes to parolees, not probationers. I.e. there are giant structural incentives from pure intergovernmental bureaucratic budget wars to move people from probation to prison and because it's controlled by judges, I.e. the prison department can't just refuse to take a trivial probationary revokee, it's a one sided fight […]

For example I got a friend that just got two years for the driving the speed limit in Texas while at a funeral, travel approved by the judge, because probation also makes it illegal to break your state law even in another jurisdiction where it's legal. He was driving 85 (the posted speed limit) in outside Austin but in Hawaii it's a misdemeanor to exceed 80 mph for any reason on any road strict liability; his PO asked him "jokingly" if he drove the speed limit while there and if he enjoyed the faster mainland speeds, he said "yes" unbeknownst to him he was being setup. His admission resulted in his probation being revoked for literally following the posted speed limit.

Charlotte Wollstonecraft writes:

The marginal prisoner in Massachusetts may be a much badder dude than the marginal prisoner in Louisiana. But here is anecdotal reason to believe he is not:

Last week in New Orleans, there were three mass shootings. Two of them happened at the same second line in New Orleans East, 45 minutes apart. In two separate incidents, a gunman opened fire at a large outdoor gathering. In total, two people died, and ten were wounded. This is not national news. No arrests have been made.

The third shooting took place in the French Quarter four days later. One of the three shooters was caught immediately. Turns out, he had already served seven years in prison for armed robbery. Last year, he was arrested again and charged with domestic battery, child endangerment, and possession of a firearm by a convicted felon. A plea deal got him out on parole, the terms of which he violated near daily according to his ankle monitor's logs. He was wearing the ankle monitor at the time he opened fire on a French Quarter street, wounding three people and killing another.

I’m including this here as a counter to Peter’s story of the guy who got two years in jail for driving the speed limit. I hear so many outrageous stories of extreme strictness and so many outrageous stories of extreme laxity (see also this post) that I’m nervous about turning the dial one way or the other compared to trying to figure out what’s going on.

Grant Gould writes:

You allude to it twice but then pass over it "for simplicity": None of these studies measure within-prison crime, which is largely not counted, tracked, tried, or prosecuted. It is not only plausible but likely that "incapacitation" is at best simply relocation of crimes. And even _that_ is leaving aside the regular drumbeat of deeply sadistic crimes by guards, which are even less counted, tracked, tried, or prosecuted.

The quality of statistics on crimes within prisons is very poor, of course; ttbomk it is not practically possible to know if the average prisoner commits crimes at a greater rate while incarcerated than while outside, or likewise the rate at which people in prison are crime victims versus those outside.

If your value function is some sort of utilitarian sum over society, you have to count those, or else your utilitarianism is just gerrymandering people into and out of the boundaries of the utility summation (in which case you can optimize utility much more simply than by incarcerating; simple Schmittianism will do the job more easily, and it's free since you don't count the cost).

I wrote this post to respond to debates (eg on California’s Prop 36) on whether prison is an effective way of decreasing the crime that normal people have to suffer in their neighborhoods. I think this is an important question that lots of people care about. Whether prisoners commit crimes against other prisoners is also important, but it’s a different question. I think people would justly distrust me if I pretended to be answering the question they cared about, but actually answered a different question.

I (following Roodman) gave two conclusions in my cost-benefit analysis - one that counted the suffering by prisoners themselves, and one that didn’t. Since I think different people will have different intuitions on this, I think it was the right strategy. The one that counted the suffering of prisoners included a general estimate of willingness-to-pay for prison which I think includes the cost of intra-prison crimes. Either way, I think being exposed to intra-prison crimes is a small fraction of the badness of prison that doesn’t change that analysis much.

I also don’t think it’s exactly right to say that incarceration only relocates (rather than prevents) crime. This may be true for murder and rape. But there aren’t a lot of things to steal in prison (not zero, but not as much as in the outside world) and the vast majority of crimes are property crimes.

JBG writes:

Some thoughts as a former defense attorney.

On "after effects," skipping all the way to length of incarceration misses a lot of what's going on for first time offenders. As your own examples note, many of the problems making it harder to make an honest living accrue from being a felon as such, and not from jail time. I'll add on that merely being *arrested* triggers a similar cascade of consequences. Your average person will be fired from their job very quickly after arrest -- either because of the arrest itself or just because it leads to missing work. And an arrest on its own, without a conviction, is sufficient to make it hard to get hired on in a lot of jobs.

But this is all specific to first-time offenders; going from someone presumed to be a law-abiding citizen to being a felon changes everything. An incremental felony after that doesn't change much. From your description, it seems like the studies are blurring this together? I'd be interested to see evidence focused specifically on first time offenders.

My guess would be that there's a large, negative effect of your first felony (all else equal) but not much effect at all of subsequent felonies. In that case, there's a very different calculus for the incapacitation vs. recidivism tradeoff for different, identifiable groups.

Undeserving Porcupine writes:

Eugenic effects of 3-5x’ing the prison population? Makes it harder for these criminals to make more of themselves.

Several people brought this up on Twitter. It deserves a full post response, but in case I don’t get around to making it - I think this is almost zero.

I realize that’s a surprising claim, but compare the Nazi eugenics program against schizophrenics discussed here. They killed almost every schizophrenic in Germany, and schizophrenia is 80% genetic, yet the next generation had the same number of schizophrenics as ever, at least within the measurement margin of error. See the post for a longer explanation of this seemingly paradoxical result.

Sebjenseb did a similar analysis and finds that if you execute the most criminal 1% of the population each generation, population level criminality decreases by about 0.1 standard deviation per 400 years. This is less trivial than I expected - it corresponds to a drop in the murder rate from 30 to 20 (possibly less for other crimes). But it's also a better case than our real scenario for a few reasons (police have 100% efficiency in arresting the worst criminals exactly in order; execution is better at preventing childbearing than prison). Maybe a real scenario is 33% decrease in crime rate per 600 years? Doesn't seem that relevant to me - even if we don’t get a singularity in the next few decades like I expect, we’ll probably get better genetic engineering or go multiplanetary (in which case founder effects will overwhelm everything else).

Publius Obsequium writes:

One thing Scott neglects is the beneficial effect prison has on kids of criminals (yes you read that right - look it up)

Here is an article making this case and citing some corroborating studies. I would stress that there are also many (probably more) studies finding the opposite, and that I haven’t looked through any of the studies on either side to check whether they’re any good.

Straphanger writes:

This analysis ignores that punishment is a good in itself. The victims of crimes deserve retribution against the people who have wronged them.

Some version of this was one of the most common comments, with opinions ranging from:

I was a bad person for not focusing on the suffering of the prisoners in prison more, especially their potential victimization by prisoner-on-prisoner violence.

I was a bad person for counting the suffering of the prisoners in prison at all, since they, as criminals, deserved no better.

Actually, the suffering of the prisoners in prison, far from being a cost or even neutral, is a positive! Just as the greatest delight in Heaven is looking down on the tortures of Hell below, one of the advantages of being law-abiding should be knowing that criminals are suffering.

Everyone was right to criticize me, because I have a confused and muddled middle position here.

I am most willing to discount the suffering of prisoners when I think of this in a game theoretic way. I imagine some sneering criminal robbing me, saying “Sure, you could stop me at any point - but then I would be suffering, so you have to let me continue my crime spree or else you’ll be a bad person, mwahaha!” Obviously the decision theory here is to - even if you were previously the nicest person in the world who would regret the suffering of a fly - strategically turn that off in this case and throw the book at the guy. This is why I’m pretty sympathetic to laws making it illegal to run over protesters who are deliberately blocking roads. The end result of legal protections for people who prey on the kindness of others is the transformation of decent people into chumps who get exploited harder and harder until they crack and become cruel just to keep up. I would rather protect the ability to be kind in general by suspending kindness against anyone deliberately taking advantage of it. And even though the strong version of this with the maniacal laughter rarely happens, I think it’s worth leaving a margin of error for when “society” or “cultural evolution” or whatever is secretly playing this strategy.

I am least willing to discount the suffering of prisoners when I remember that the above has almost no relation to reality. See the section on criminal psychology above. Tough-on-crime people like to say they’re all based and IQ-pilled, but the average criminal is an IQ 75 moron with the impulse control of a young child. Probably they are genetically suited to some kind of hunter-gatherer tribe with strong kinship bonds and zero superstimuli; in modern society, they are totally doomed. I’m not sure what our goal is here in creating a bunch of people incapable of living cooperatively in modern civilization, and then, when those people inevitably fail to live cooperatively in modern civilization, saying “Haha! Now you’ve outed yourself as an evil person who deserves to suffer!” and torturing them for a few years to “get our revenge”. If you’re going to take that perspective, you might as well torture three-year-olds who throw tantrums in the grocery store.

Someone, I can’t remember who, had a thought experiment with the society as far beyond ourselves as we are beyond the average criminal. Maybe it’s a society of Buddhist monks, or of angels. Raising your voice at someone, going one mile above the speed limit, or stealing a glance at a woman’s cleavage in their society is considered as outrageous as assault, drunk driving, or rape would be in ours. So what happens? Do you never commit a single misdeed even in your heart? Or do you inevitably slip, then spend the rest of your life “deserving” “torture” for your infraction? If the Buddhist angels are really mad (or, I suppose, sad/disappointed/victimized, since they’ve transcended anger), do they deserve to take out those feelings by inflicting arbitrary unbounded “retribution” on you? If you object “But glancing at a woman’s cleavage doesn’t do her that much harm, really!”, then I’m not sure how you get away with thinking that X years stuck getting raped in a cage for shoplifting is “proportional” either.

My uneasy synthesis is that criminals have nominated themselves for the short end of a tradeoff. If we have to balance their suffering vs. that of law-abiding citizens, we should weigh that of the law-abiders somewhat higher. But we shouldn’t weigh criminals’ at zero, and we definitely shouldn’t punish them just for fun.

I hold this position pretty strongly with regard to the people who just abstractly think making prisoners suffer is nice. I have a harder time knowing what to think of people who want revenge for crimes committed against them personally. A criminal murdered my great-grandfather in a robbery gone wrong; my great-grandmother (who I never knew) was apparently an extremely nice person but saw red, demanded the death penalty, and was enraged when the jury settled for a lengthy prison term. I can’t promise I would behave any differently than she did in her situation. I content myself with thinking that the incapacitation-optimal amount of prison (probably 20 years to life for a murder) is already pretty extreme and hopefully satisfies most people’s revenge fantasies. But I’m pretty split about this. If I imagine someone hurting my family, 20 years in a minimum-security Swedish prison isn’t going to cut it. But if I imagine myself on Judgment Day before the throne of God, being asked to account for any suffering I chose to inflict upon my fellow man, the only answer I would really be comfortable giving is that I did it for the greater good of preventing/deterring future crime and protecting the innocent. I do sort of understand the emotional response that makes some people feel that maybe anyone who has transgressed has opened themselves up to infinite punishment in the name of justice - but on Judgment Day this is exactly the sort of thing I will be desperately trying not to remind God of!

I tried to limit the degree to which I discussed this in the original post, because I think it’s exactly the kind of culture war scissor topic that people will get too excited about, and that there are other arguments (the superiority of police deterrence over prison) which let us sidestep this whole issue.

Joseph writes:

A note on shoplifting. If you can't punish shoplifters because you don't have the resources to try all of them, then you have two main options to change that.

(1) Fund some kind of "shoplifting task force" (or petty crimes task force if you want broader reach, but this will spread your efforts). Hire more prosecutors, judges, public defenders, bailiffs, court reporters, etc. and try more cases. If it's constitutional, you could target this effort at people with multiple prior recent arrests first, although the population will get the idea that everybody gets a few free misdemeanor tickets.

(2) Increase the difference between the minimum sentence that you get if you go to trial vs. pleading out. In other words, create "first degree," "second degree" etc. shoplifting and make the penalty for the higher degrees painful enough that people will plead to third degree shoplifting and do a year in prison rather than risk a conviction for second degree and five years.

#2 is inhumane and has been reasonably compared to medieval practices of confession under torture, but is also the way we manage our trial dockets in the US, unfortunately.

Sol Hando (blog) writes:

I am now sold on the Australian model as a solution to basically all crime.

No, not modern Australia, which sits comfortably above the European system and below the American one in terms of incarceration rates, and doesn't seem to be doing anything novel, but the Australian system as it was for the United Kingdom a few centuries ago. Penal colonies.

If the problem with increasing prison sentences to the point we eliminate 90% of the crime is that it would cost insane amounts of money, then shipping those prisoners to a completely separate society somewhere far away would have the incapacitation effect (which seems to be by far the most important factor), without any of the significant costs. A one-way flight ticket is maybe a thousand dollars? Pretty much anywhere in the world.

If you think penal colonies are cruel, present the option to the criminal to join one, or our current system. If 5+ years of imprisonment essentially breaks all your social bonds anyways, it seems a much preferable alternative to have freedom in a new, if harsh, land, rather than be imprisoned in a literal prison near to home. If you're worried that penal colonies will be dangerous and deadly, as they're full of criminals, that's sort of what prisons are already. Except with a colony you can go out to the sticks and rarely interact with other people, and can have the means to readily defend yourself.

Unfortunately it doesn't look like there's anywhere left that could function as a modern day penal colony without being cruel. The whole idea is incapacitation, so it doesn't work if we just ship them to Montana or something and call it a day, as they could easily take a bus out of there. It would have to be separated enough that returning to society without permission was sufficiently difficult. Even a large island (let's say we sacrificed Hawaii's big island for this purpose) can easily be escaped if not for significant monitoring.

I think Robert Heinlein's, The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress should be our model for an actual solution. The moon is far enough away that it would be quite difficult to get back.

I think Sol is overestimating the difficulty of preventing escape, and underestimating the difficulty of everything else.

People call Gaza an “open-air prison”, and the comparison makes sense. It contains two million Palestinians, separated from Israel by a wall, barbed wire, and military guards. Security isn’t infallible (see 10/7), but the breach required a near-state level of resources (including funding/arms/supplies from Israel’s enemies) plus a rare catastrophic blunder on Israel’s part - and all it did was get a few thousand Gazans over the wall for a few hours.

But Gaza is just a coastal area with a wall around it. America has plenty of isolated coastal areas. The US prison population is lower than the population of Gaza, so a Gaza-sized strip could fit all prisoners with room to spare.

But I think Sol is imagining an area with enough fertile land that inhabitants could set up farms and be self-sustaining. That’s a bigger problem. There are ~1.2 million prisoners in the US. In theory, one person needs an acre of land to support themselves through subsistence farming. 1.2 million acres is the size of Rhode Island. But this is the best case scenario where the land is completely tiled with one-acre farms - which means prisoners are no longer isolated from other prisoners, and probably preying on/murdering them. Which is more likely - that a murderer settles down to do backbreaking farm labor, or that murder their neighbor and take their crops?

The alternative is a Gaza Strip situation where you’re not even trying to farm, and just ship in food. But that requires prisoners to be near distribution centers, which again gives them a lot of opportunities to commit crimes against each other. I would imagine this looking something like Haiti, with urban gangs fighting each other until eventually the baddest dude becomes some kind of warlord. Haiti is probably still better than prison, but I could see this getting worse. Why shouldn’t the winning gang kill all new prisoners who enter (to prevent them from consuming supplies)? If the winning gang is race-based (eg Aryan Nations), would they enslave the other races?

Sol suggests giving prisoners a choice between a penal colony or a regular prison, which I agree would potentially limit some of the downside. But now we have a new problem - even if the penal colony has fewer atrocities, relatively speaking, it may have more photogenic atrocities, in the sense of some sort of public torture that produces outrage instead of the slow burn of sadism and misery that normal prisons produce. The story of modernity is people trying to exchange photogenic atrocities for boring atrocities in order to avoid having negative New York Times articles written about them. I worry the penal colony might end the same way.

Here’s an even more hare-brained scheme: if this would devolve into Haiti, why not skip the middleman and pay Haiti to take our prisoners directly? It probably couldn’t make them any worse-off, and they could use the money. It would be win-win!

Melvin writes:

There seem to be reasonable solutions to prison gang power. My preferred solution of solitary confinement for everyone (enriched solitary with books and entertainment, not the semi-torturous sensory deprivation kind) is controversial but we can at least cut down prisoners' social interactions considerably so that each prisoner only interacts with (say) half a dozen others. A prison could consist of small isolated pods separated by thick walls.

Yeah, everyone I know with experience says that solitary confinement is torture, but I would naively expect to prefer it to normal prison. Maybe at least give prisoners the choice?

I do think solitary might be more expensive - El Salvador has 100 (!) prisoners per cell to save money; I don’t know how many America has but I bet it’s not great.

justforthispost writes:

This is why I (definitely on the thin end of the bell curve vis. leftism on this website) support public corporeal punishment over prison.

I honestly think we should bring back the cane and the stocks. If you get caught lifting razors from target the state should mandate spending three days locked in stocks In front of city hall and getting your feet switched; this is infinitely more humiliating the prison, much less disruptive, much less likely to kill people, gives cops less chance to do cop things (beat people to death, let them die in prison from preventable medical conditions, rape people in prison, etc.) and much it's much cheaper!

I previously believed this, but this post makes me more skeptical. Since most of the benefits of prison come from incapacitation rather than deterrence, we should expect this to have limited effect - although some people point out that something public, sudden, and dramatic might have better deterrence properties! I think if first shoplifting arrest is a warning, this would be a good way of dealing with the second and third, and then after the Xth strike we give up and just try to lock you away from society.

Robert Huben (blog) writes:

Fun dystopian mechanism for private companies to increase deterrence: increase all sticker prices 1000x, while offering 99.9% discount coupons. Since shoplifting goes from a misdemeanor to a felony at a certain dollar amount ($750 is mentioned in the article), this means that shoplifting ~anything is a felony, increasing deterrence while leaving normal customers unaffected!

I'm not a lawyer, I'm supremely confident this will work. The hardest part would be randomly assigning stores to intervention/control groups, so the criminologists can measure the effects.

You laugh, but this is exactly how our health care system works.

AJKamper writes:

One other comment I want to throw in here. Hang around for a while with correctional workers, at least in Minnesota, and you will eventually hear someone talk about “evidence-based practices,” usually right before they spit at the ground. Coming from secondhand medical background, this confused the hell out of me for a solid six months. A) In medicine, EBP is a set of practices designed to make sure that commonly used interventions, you know, work. B) Evidence seems… good? Not here. A new director might be described as “super EBP” with a roll of the eyes.

I eventually worked out that in practice, EBP represents a rehabilitative, “soft on consequences” approach in prisons that a lot of front-line workers, especially older ones, think is ineffective at best or just plain too kind to offenders who deserve worse. So there’s a major divide between Central Office people who are trying to rehabilitate the inmates based on “best evidence,” and the guards and case managers who think that time should be hard. It’s a pretty good microcosm of the current epidemic crisis, actually.

Michael writes:

Skarbek's book "The Social Order of the Underworld: How Prison Gangs Govern the American Penal System" is a great read.

The key point is that, because most criminals expect to go to prison, they know they will someday be at the mercy of prison gangs who have the power to inflict violence on the inside. This gives prison gangs enormous power outside of the prison walls; non-prison gangs usually pay tribute to a given prison gang.

(This incidentally is what worries me about El Salvador. Having all the gang members in prison right now might be like having guerrillas driven up to the mountains; the state may be ceding its monopoly on violence in a certain part of the country and this could eventually be a problem even if the rest of the country is safe in the meantime.)

Putting a dent in the power of prison gangs would be intrinsically good and probably help with crime on the outside.

Unfortunately solutions to this are probably unpalatable. Removing the gangs' power to commit violence and smuggle drugs would look like making conditions better and safer for prisoners (undesirable to the right), but would require large increases in funding for prisons alongside stricter security (undesirable to the left).

However this is an issue that's nicely orthogonal to "turning the knob" of more/less sentencing, so I figure it's worth mentioning.

Yeah, this is an interesting point. There’s a good interview with Skarbek in last month’s issue of Asterisk, I think it will be online shortly.