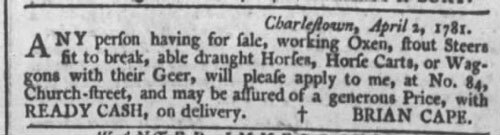

(via Newspapers.com)

Before postal systems came into place, delivering goods basically required a cash-on-delivery approach

The first possible reference to “cash on delivery” or its sibling “collect on delivery” I can find dates back roughly 260 years.

In a 1781 classified ad in the Charleston, South Carolina Royal Gazette, a man named Brian Cape asked for the services of someone who had “working Oxen, stout Steers fit to break, able draught Horses, or Wagons with their Gear.” He offered “READY CASH, on delivery,” for this gear.

Because, honestly, would he have had a choice otherwise? The concept of credit was still fairly unusual at the time, and when you’re purchasing something that expensive, you likely needed to pay for it in full at the time. Now, compare that to how you might pay for a Domino’s Pizza to come to your door in the present day. If you don’t use a credit or debit card, you can still pay cash, but for many obvious reasons, the pizza seller would prefer the money up front—because, if you stiff them, they’re out money on gas, production, and labor.

Food delivery remains one of the most common cash-on-delivery models, though that’s changing. (waldopepper/Flickr)

Just this week, there was a guy in the news whose biggest problem would be solved if pizza delivery shops didn’t use cash-on-delivery: Jean Van Landeghem, a poor fellow from Belgium who has received repeated orders for pizzas on a near-daily basis for almost the past decade.

He’s ultimately the exception to the rule, however. In many ways, C.O.D. puts the ball in the court of the consumer, who gets the ability to inspect the thing they’re accepting before paying for it, which means they can turn it down. That, of course, means that much of the risk gets placed onto the seller, who may have to cover the shipping and return costs as a result.

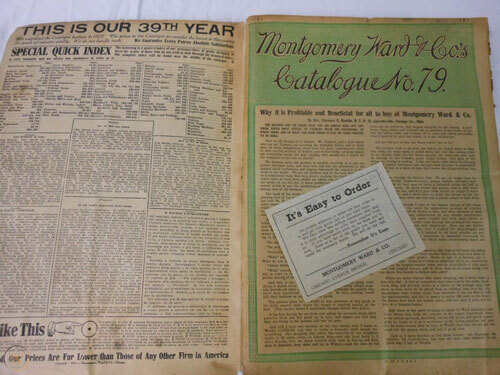

But companies were often willing to take the risk if it offered a way to shore up trust in a mail-order business model. In November of 1873, for example, the Chicago Tribune, without any proof whatsoever, attempted to light ablaze the business model of Montgomery Ward, claiming that the operators of the mail-order firm were “scam artists.”

“Another attempt at swindling has come to light,” the article starts. “This time it is a firm, Montgomery, Ward & Co. by name, and the parties specifically aimed at by the project are no less important a body than the Grangers.”

But a month and a half later—on Christmas Eve, no less—the Tribune published a full retraction, after the newspaper investigated the business and realized it was “a bona fide firm, composed of respectable persons, and doing a perfectly legitimate business in a perfectly legitimate manner.”

A Montgomery Ward catalog, circa 1910.

Montgomery Ward had to win over the trust of its target audience, and one way it did that was by offering C.O.D., so that consumers could inspect the goods before they purchased them—not a small task, and not a cheap one, either.

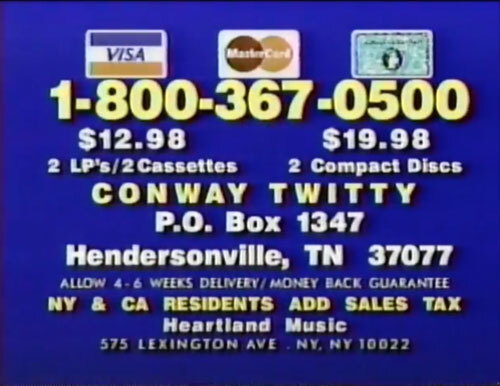

It was good for Montgomery Ward, and a widely used model for more than a century in North America. But by the 1980s and 1990s, the way that many people heard about the model was through commercials that specifically dissuaded people from paying for things using C.O.D.—in many commercials, outright telling people not to send it (often using the phrasing “Sorry, no C.O.D.”), or by pushing them to use a credit card or to send a check or money order instead.

Like airplanes telling people not to smoke, it felt like nobody was actually doing it, but they still had to say it anyway.

This type of commercial, with a mailing address baked in and a voiceover discouraging its use, is where many millennials learned about C.O.D.

An example of this is Heartland Music, the Lawrence Welk-associated music reseller that I wrote about in 2017 and republished back in January.

“Use your credit card and save C.O.D. charges by calling toll-free, 1-800-367-0500,” one such commercial, featuring Conway Twitty, says near the end.

The C.O.D. model has arguably been ripe for abuse—one can imagine, just like with the guy saddled with fake pizza orders, someone repeatedly ordering Conway Twitty records via C.O.D. to torment a country hater—but in some contexts, it persists.