Takeaways

No takeaways this time, it'll spoil the story. It’s a 3k word post that could cut off in email, so you might want to click through to read on the substack site. There’s also a note towards the bottom on free postcards for subscribers!

Let's start with a story about stories.

Bestselling author Kurt Vonnegut is known for Slaughterhouse-Five, Cat's Cradle, and many other works. In his autobiography, he claimed that this was his greatest contribution to culture:

|

So, stories have shapes, he says.

What does that mean? Kurt explains [1]:

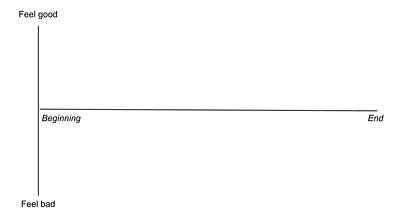

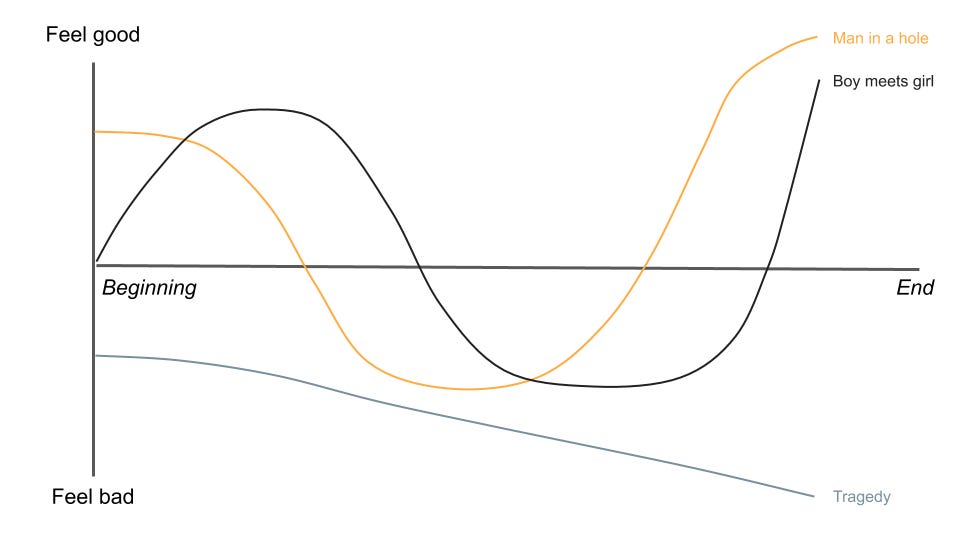

Imagine you had a graph, with good fortune and bad fortune on one side, and the other side showing the progress of the story from beginning to end.

|

You could plot any story on this graph to see its shape. And if you plotted all the stories in the world, a couple of common patterns would emerge.

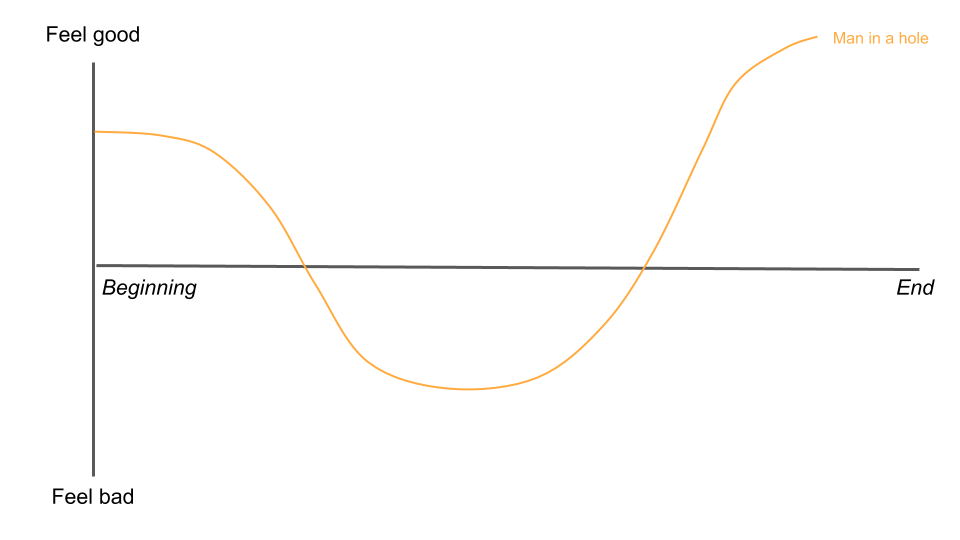

For example, in The Godfather, Michael starts off happy, but the family gets in trouble and he is forced to leave the country. He eventually returns, regains control, and kills most of his opposition, becoming the godfather of the city's mafia. We'll plot this on the graph and call it a "man in a hole" type of story. Man is doing well, falls in a hole, then gets out and is better than before.

|

On the other hand, in About Time, [2] the main characters fall in love, lose each other, and then find each other again after a series of events. We'll call this a "boy meets girl" type of story. As you can imagine this is typical for many romance movies.

|

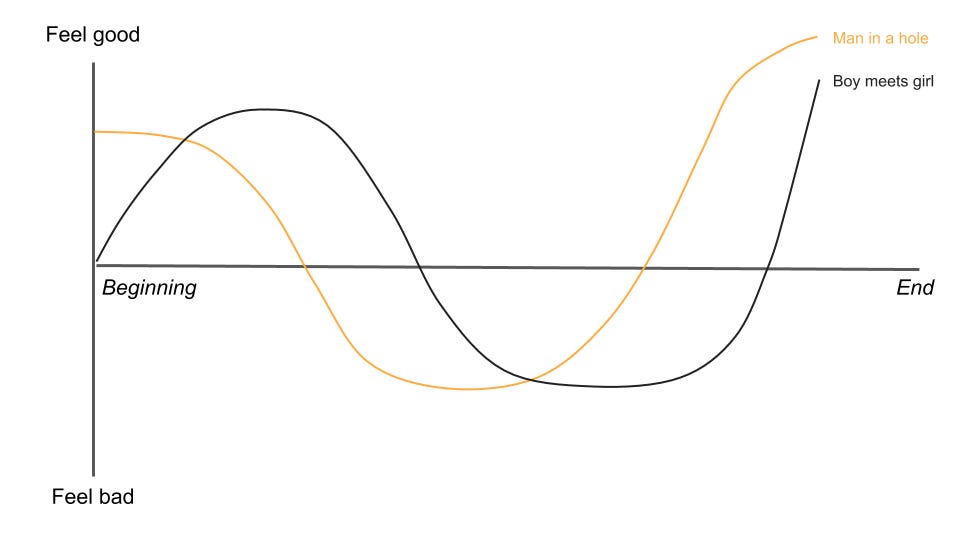

And in a story such as The Metamorphosis, things just keep getting worse for our protagonist as he turns into a bug and dies. This would be a "tragedy".

|

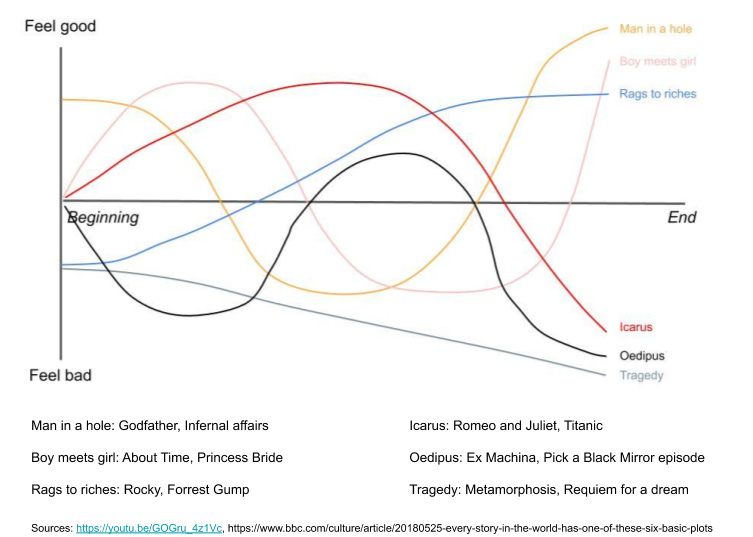

In addition to the shapes above, Kurt thought of a few more that could work. A "rags to riches" story could involve a steady rise, an "icarus" story could involve a rise and then a fall, and a "oedipus" story could involve a fall, rise, and a fall again.

|

Building on this idea, a team of researchers from Vermont and Adelaide used machine learning to classify 1,327 famous stories on Project Gutenberg. They found that the majority of stories could indeed be grouped into a few major types. See the footnote for details on their methodology [3].

|

They've replaced "boy meets girl" with "cinderella" here, but it essentially shows that Vonnegut was right [4]. Stories have shapes, there are a few standard shapes.

How is this relevant? You came here for stock tips and startup trash talk [5], what's up with all the notes about narratives?

I'll make the link shortly, and for now let's just keep those story shapes in mind.

1. Stocks have shapes

Last month, we discussed one reason your investment pitch sucks: you aren't accounting for consensus.

This month, let's discuss another common reason that can be even more frustrating.

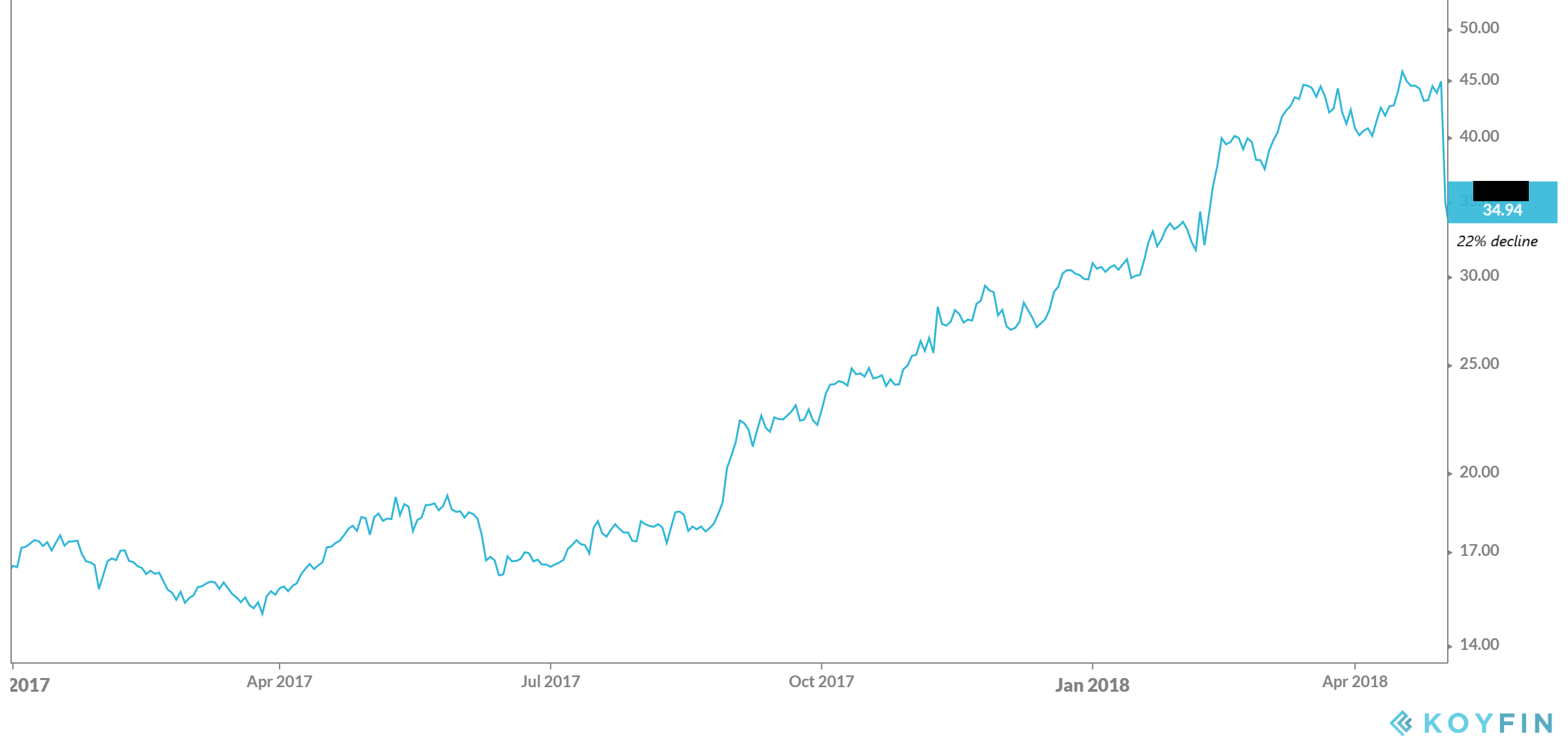

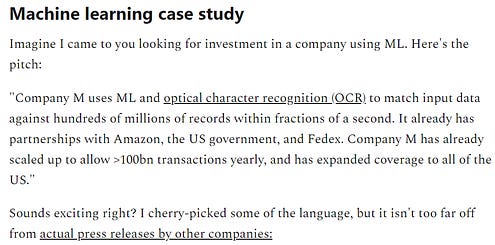

Consider this company as of Apr 30, 2018:

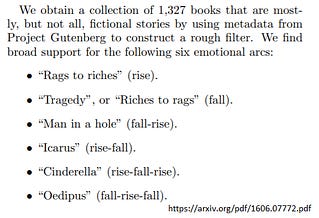

Company X is an internet company, mainly making money off app subscriptions with its monopoly in an expanding consumer category. It has 7 million total subscribers, of which 3 million are subscribers of its main app. It's growing revenue ~30% year over year. EBITDA (a type of earnings metric) margins are 40%. The stock price is at an all time high, having more than doubled in the past year [6].

|

Looks pretty good, maybe worth researching further to see if you'd want to own it.

Also consider the same company as of May 1, 2018:

Company X is an internet company, mainly making money off app subscriptions with its monopoly in an expanding consumer category. It has 7 million total subscribers, of which 3 million are subscribers of its main app. It's growing revenue ~30% year over year. EBITDA (a type of earnings metric) margins are 40%. The stock price is at an all time high, having more than doubled in the past year. Facebook just announced they're planning to enter the category

|

The company's fundamentals haven't changed, but that 22% price decline within a day clearly shows something has. That, of course, is the story that investors are telling about the stock.

For what is a pitch, but a story about the stock?

On Apr 30, the consensus pitch [7] was that the company had been growing fast at a high margin with no competition. Investors kept buying the stock, and the price kept rising.

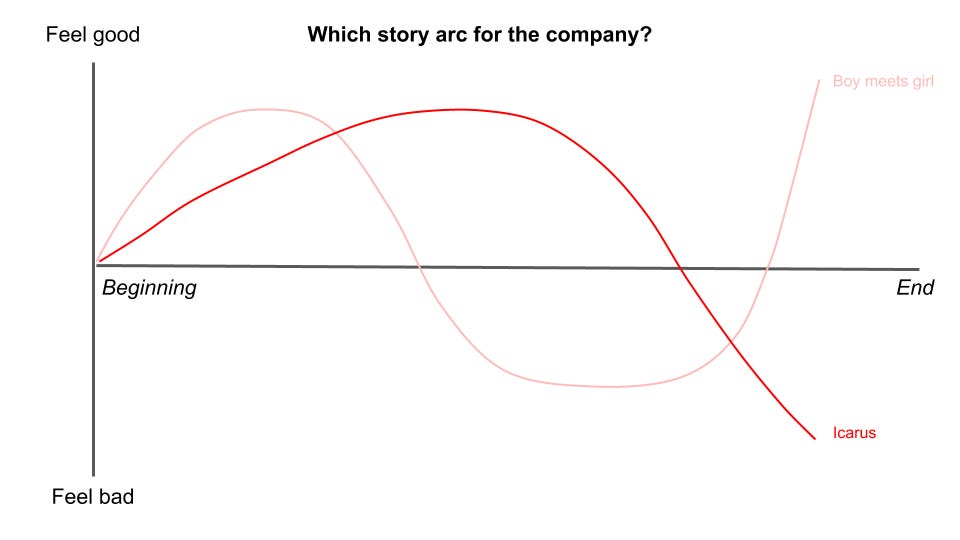

On May 1, the story came to a fork in the road. You could either say that Facebook was going to crush this company, and you should sell as much of it as you can. Or you could say that the fear was overblown, Facebook's non-core product track record is bad, and you should buy as much of it as you can.

Sound familiar?

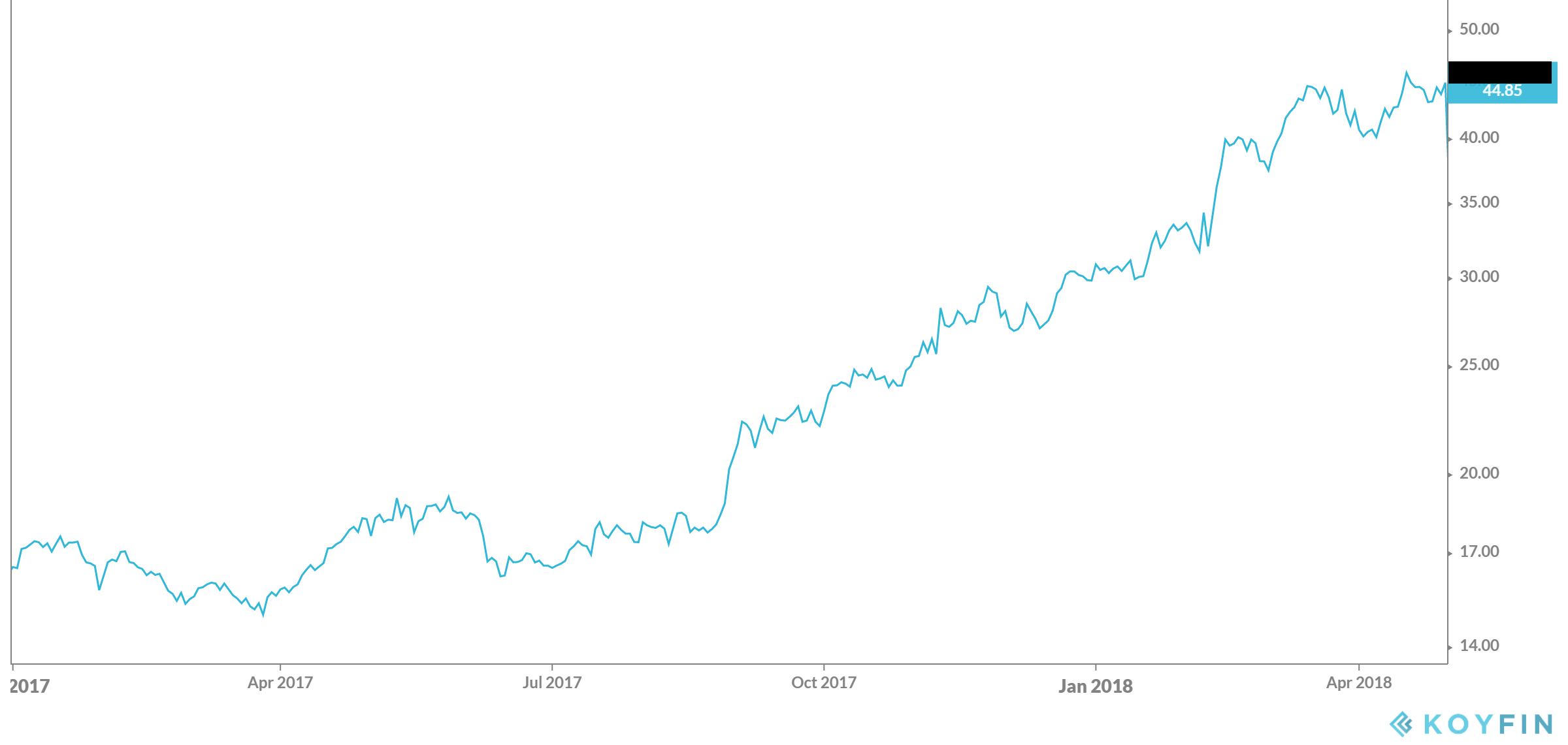

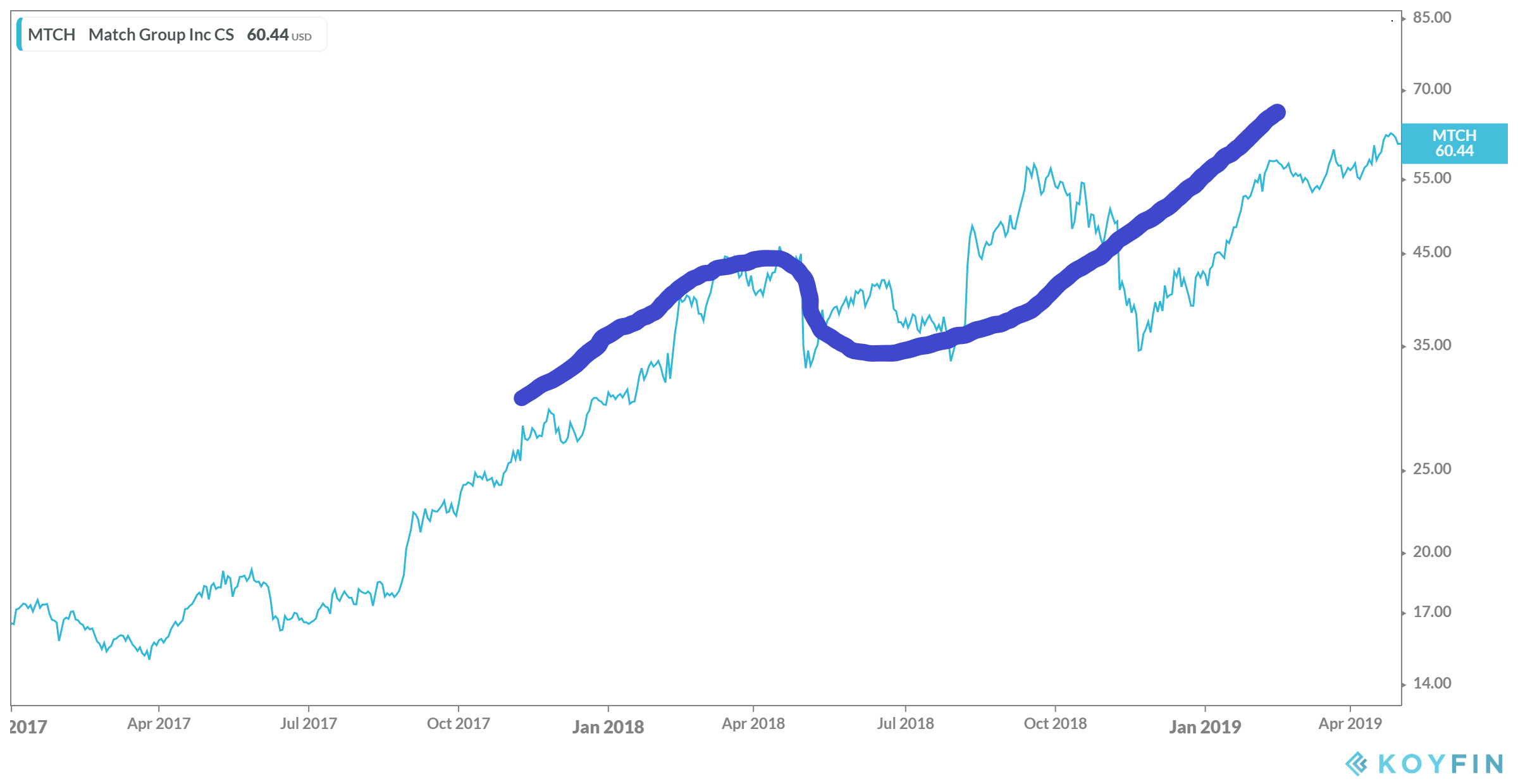

|

The company in this case was Match.com, parent company of Tinder, and would go on to double in stock price again about a year after that decline. Boy meets girl worked out.

|

On May 1, both stories were equally valid, and you had smart investors taking either side of that trade. Importantly, the stock price reacted even before any actual change happened to Match's business. The story had hit a crossroads, and investors were now choosing different sides. The ones who thought it would be like "icarus" lost, and the ones who thought otherwise gained. As stories change, so do stock prices.

What does this mean for your investment pitch? It implies that storytelling is key to a good pitch. The better you can tell a story, the more likely it will get traction. Both with your boss, and other investors. It's annoying, but the "best idea" is very frequently the "best story."

Why does it matter if your idea gets traction? Remember that investing is not just about being right, but also about getting others to realise you're right. You do not make money by sitting on a great company if the price doesn't move [8]. You make money by being against consensus and right, but if you can't bring others to your side, you'll forever be against consensus and wrong. The stock market may be a voting machine in the short term and a weighing machine in the long term, but if you don't spread your story your machine's broken [9].

Where should you focus on? If your investment horizon is shorter term, you'll likely be looking for inflection points in the story arc; otherwise known as catalysts. For example, you'll want to have a credible case for why a stock is currently in a hole, and why it's looking like it'll get out. If your time horizon is longer term, perhaps you might be more interested in "rags to riches" types of stories.

Of course, stories can go both ways. I showed an example of a stock that recovered, and could have easily picked one that went the other way. People were telling great stories about Enron, Tilray, Luckin, and more, before they all imploded. All the storytelling in the world can't magically create revenue (though it did create a lot of money for whoever exited their positions in time).

I'm also not saying that all you have to do is fit stock prices to curves to make money [10]. What I am saying is that the perception of stocks does follow a narrative arc, and that can often be seen in the price. Knowing what story you're trying to tell will improve your pitch.

We've known for a while that fundamentals aren't all that drive stock prices; see Shiller's work on a history of stock forecasting theory. The ability to tell a good story is key to getting investment ideas across. Why do you think so many investors talk about their ideas publicly? The more you can convince others of your story, the more likely you'll make money as an investor.

Investors tell each other stories, and bet on what they hope to be true.

2. Startups have shapes

Storytelling matters in tech as well. It's how startups raised millions with just a pitch deck, or how Masa raised $45bn in an hour from the Saudis. In the former, startups told VCs how they could grow to $1bn. In the latter, Masa convinced Mohammed bin Salman that he could grow to $1tn. Their track record undoubtedly plays a part, but the picture they paint in investors' minds was key in securing funding.

No one wants to back a loser, so it's up to the startup to tell their story in a way that makes them look best. They're trying to position themselves as a "rags to riches", while investors are trying to determine if they're a "icarus". When a VC rejects a company, they're implicitly saying that they think the story is too boring. Avoid boring stories.

This also implies that startups are incentivised to tell the most exciting story about themselves. In doing so, most will stretch the truth as much as possible. They'd much prefer to sell you on the ending chapter, rather than the beginning. Experienced investors know this, though the public is probably less aware. Whether this becomes fraud or not is a fine line.

Let's imagine this scenario:

Your company was too early to a trend, and you've gone into debt trying to save it. You get a call from a college kid, who tells you that your product is great. So great in fact, that he's writing a program for it that will make you lots of money. You're interested, and agree to meet the kid for a demo.

On the other side of that call, a nervous college kid hangs up, realising that he's close to getting his first contract. The only problem? He doesn't even have a copy of your product, let alone any working program for it.

Fraud, or optimistic thinking? Perhaps you're thinking that you should avoid doing business with this kid forever. If you did, you just missed out on Bill Gates, and the forming of Microsoft. Sometimes a story that's not entirely true yet can turn into the truth.

Let's imagine another scenario:

You meet with a young founder, who pitches you on a revolutionary healthcare solution. The prototypes you're shown aren't that polished, but they're confident in eventually building a finished product ready for wide scale usage.

The founder keeps getting more publicity, appears on multiple magazine covers, and signs big deals with pharmacies. The board of directors also seems full of famous people, though you aren't quite sure why so few of them have healthcare experience.

The startup in this case, of course, is Theranos, which would go down in flames as one of the bigger frauds this decade. Holmes had such a fantastic story that everyone wanted to listen to it; investors report being "captivated" by her pitch. If the lesson you took from the Microsoft scenario was "believe all exciting stories", you can see why that will be a problem. Sometimes stories that aren't true yet will forever be fairy tales.

That line between fraud and optimistic thinking can be thin. Steve Jobs was famous for his reality distortion field, or ability to convince anyone that something was possible. I'm sure Holmes at the time believed that she could do the impossible, much like so many other startup founders. We judge them by their results now, but you can easily imagine a scenario where Steve's return to Apple just didn't work out.

Or consider other startup failures where a plot twist could have given a different ending. WeWork, Pets.com, Moviepass etc all had great stories but have fallen from grace. WeWork might be doing better if it hadn't grown so fast, Pets.com has a spiritual successor in Chewy, and Moviepass might have worked with more funding [11]. Right up to the end, I'm sure all the people within the company were hoping that an upswing in their story arc was around the corner.

Besides investors, your startup story also matters to employees, customers, and the competition.

Equity is a stake in your story. Since employees at startups are usually paid less in cash and more in stock, they're making a bet that your story will be a good one. The hard part in recruiting talent is convincing them that there's enough potential in the company to sacrifice better, safer alternatives [12].

Customers look at your story before deciding to buy. They think about what your product could do for them, whether that's time savings, reduction in effort, elevation of status, or more. As discussed before, nobody likes to back a loser.

Your competition is also looking at the story you're telling, and making plans according to what you seem to be doing. If you're growing faster than they are, they'll be trying to find out why. If you're doing worse, they'll be using that opportunity to pitch their own story to your target audience.

The importance of stories to startups is well known. Beyond attracting investors, it also matters for anyone else the startup interacts with. As Bill Gurley from Benchmark put it:

In today’s unique Internet business environment, the art of storytelling has taken on increasing importance. Because of “network effect” and “increasing return” phenomena, many people believe that first movers (or at least companies that are first to reach a significant scale) will most likely take the lion’s share of an Internet market.

Companies tell us their stories, and work to make them true. .

3. Shape of you

We started with a story about stories.

Let's end with a story about the self.

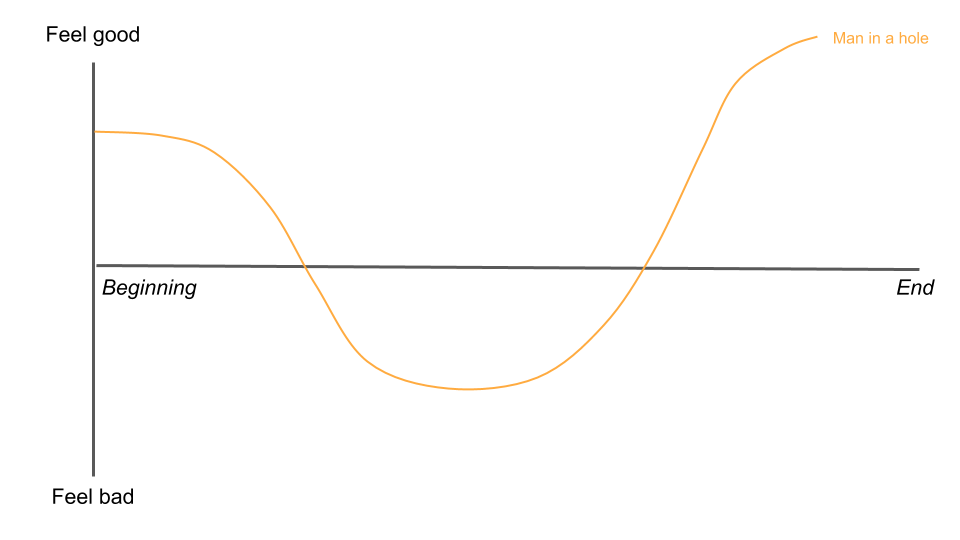

Once upon a time, there was a person who left their home to explore the world. They experienced ups and downs, and at their lowest point were suffering unimaginable pain. But they overcame that, and grew to become better than before.

Sound familiar?

|

Whose story is this though?

It could be the story of Jesus, from Christianity.

It could be the story of the Buddha, from Buddhism.

And it could even be the story of you.

We're all protagonists in our own story arcs, continuously trying to adjust our stories up and to the right. Through a combination of luck, skill, and effort, some of us may already feel like we're there. Others may feel they've been stuck in some unrelenting tragedy. It's up to us to create our own story, and we live with the consequences of our choices. Life is unfair, but there are still things we can do of our own accord.

Because we're our own authors, it also means we don't know the full story arc of others. We can see them enjoying life, not knowing how much misfortune they had to go through. We can see them experiencing misery, not knowing how much they've tried to prevent it. We'll compare where they are vs where we've been, and feel frustrated that our average experience is not as good as their highlight.

All the world's a stage, but we're not players, we're the director. We alone decide how much effort we want to put into crafting our narrative. Telling yourself you’ll succeed doesn’t necessarily mean you will, but believing your story arc is bound for tragedy is a good way to ensure it becomes one.

People tell stories and it's an enormous part of what makes us human. We will do an awful lot for stories, and endure a lot for stories. And stories, in their turn, help us endure and make sense of our lives.

You can tell me a story, and it's up to you to make it true.

Other

Does Commodification Corrupt? Lessons from Paintings and Prostitutes

Spatial is allowing AR/VR users to attend meetings with desktop users

Weddell seals make tardis sounds. h/t @rosetazetta. There's also a 2 hour version that I may or may not have completed listening to while writing this.

Subscriber milestones and free postcards

I hit an internal goal for free subscribers since the last newsletter, which calls for a celebration. As some of you may know, I also love snail mail [13]. Reply directly to this with your address if you'd like to get a postcard! I'll cut it off after some arbitrary point where I'm too tired to send more so first come, first served here.

I haven't hit my goal for paid subs yet, so here's the semi-annual shameless self-promo. Did you know I write paid articles weekly? The articles are much more random than the monthly, but join and read about the intuition behind neural networks, the buyside investing tech stack, and finding aliens [14]. Happy to forward previews to anyone.

|

Footnotes

Both in his autobiography, as well as his talk here

I will not stop shilling this movie; it's one of my favourites

The full paper is here. They used three methods in their analysis, and all showed similar results. These methods were Principal Component Analysis / Singular Value Decomposition, hierarchical clustering, and clustering with unsupervised machine learning. They first applied sentiment analysis to get the emotional value throughout the stories. I'm unsure how exactly they used SVD, and it seems like they applied dimension reduction, then extracted the top features from a similarity matrix, finding the top story types that were able to explain the majority of the variances. The hierarchical clustering seems to be a standard dendrogram to cluster the types of stories. The unsupervised machine learning used Kohonen’s Self-Organizing Map, which looks to be an algorithm for clustering groups together, doing something like K means.

Technically, Vonnegut separates boy meets girl from cinderella, as cinderalla has a more stepwise buildup and a sharp drop before recovering. They're similar enough to me that I've grouped them together. Vonnegut also proposes a single flat line for stories such as Hamlet where "nothing happens". I disagree with such a shape, and have left that out for simplicity. For a different take on the types of stories, Christopher Booker discusses seven basic plots

Please do not have come here for stock tips and startup trash talk, you'll be disappointed that I do not do the former and only occasionally do the latter.

8K for the company here, though you'll spoil the surprise.

Let's ignore what the shorts were saying for simplicity, the price performance implies people were bullish.

Yes, I know dividends exist; they're less important in driving shareholder return.

I've never really understood what a voting machine meant; I think it just refers to a machine that is keeping a running tally of the votes and hence changes all the time.

People who do technical analysis for a living would disagree here.

These are all hypotheticals, and there's no real way to come to a conclusion here. Is it unrealistic to expect Moviepass to get a large subscriber base while setting cash on fire? I mean, it really depends on the amount of cash they could burn right? What if Softbank had given it money instead of WeWork?

Some people might disagree that traditional companies are safer than startups. There's an argument to be made that working tech gives you safety for your career but not your job. I'd say that for most people getting laid off still sucks, and can be significantly financially damaging.

A writer likes to get writing? Gasp.

Do note that, as I’ve mentioned before, all posts eventually go on to my personal site after a long delay