|

Black lives matter. This document has an exhaustive list of places you can donate. It’s also got an incredible library of black literature and anti-racist texts. Donate, read, call, and email your representatives. We’re all in this together.

It only took nine minutes for Bayern Munich’s season to start to explode. First, it seemed like a penalty. They’d be down a goal -- at least, 75-percent of the time they would be -- and Jerome Boateng would have to play 85 minutes on a yellow, with a hand taped behind his back. Then that evil little monitor decided otherwise. The refere jogged over from the VAR screen, made that scary little square with his pointer fingers, and things only got worse from there. No penalty, but Boateng was gone, off on a red. Eintracht Frankfurt couldn’t convert the free kick, but it only took 16 minutes before their first went in, and then eight more for the second goal to drop.

The match ended, 5-1, in favor of Frankfurt -- a result that symbolized everything gone wrong in Munich. Their reliance on a 31-year-old Boateng belied a failure in forward-thinking. What was he still doing back there? But more than that, this was Niko Kovac, getting trampled by his former team. Bayern had hired Kovac on the back of his expectation-exceeding success with Frankfurt. However, he’d boosted the club up the table with an organized, defense-first approach. Could that really work at Bayern, the leading club in a country that’s itself leading light in the movement toward progressive, aggressive attacking soccer? His new team was now giving up five goals and his old cub, with him gone, was the one scoring for fun.

Nine months later, Kovac coached his first game for Monaco in Ligue 1. The same day, Bayern Munich won the Champions League.

Can Hansi Flick do anything wrong? Lemme raise my hand first. When I wrote about Bayern’s decision to sack Kovac after the Frankfurt loss, I didn’t even mention Flick’s name, let alone consider him as a long-term managerial option for the club. Joke’s on me, huh?

The big question before the match against PSG -- posed by the likes of, say, me -- was supposed to be this: how will Bayern counter PSG’s counters? They’d conceded good chances all year long, even to a wilting-before-our-eyes Barcelona and Lyon team without a single double-digit scorer in the starting eleven. Turns out the only personnel change that mattered was the one he made -- and no one else saw or cared to mention. Kingsley Coman came in for Ivan Perisic, and then proceeded to play the game of his life, against his boyhood club.

The 24-year-old Frenchman outplayed that other, not-quite-as old Frenchman. He’s scored one header in five years of Bundesliga play at Bayern, and what a day to get another one.

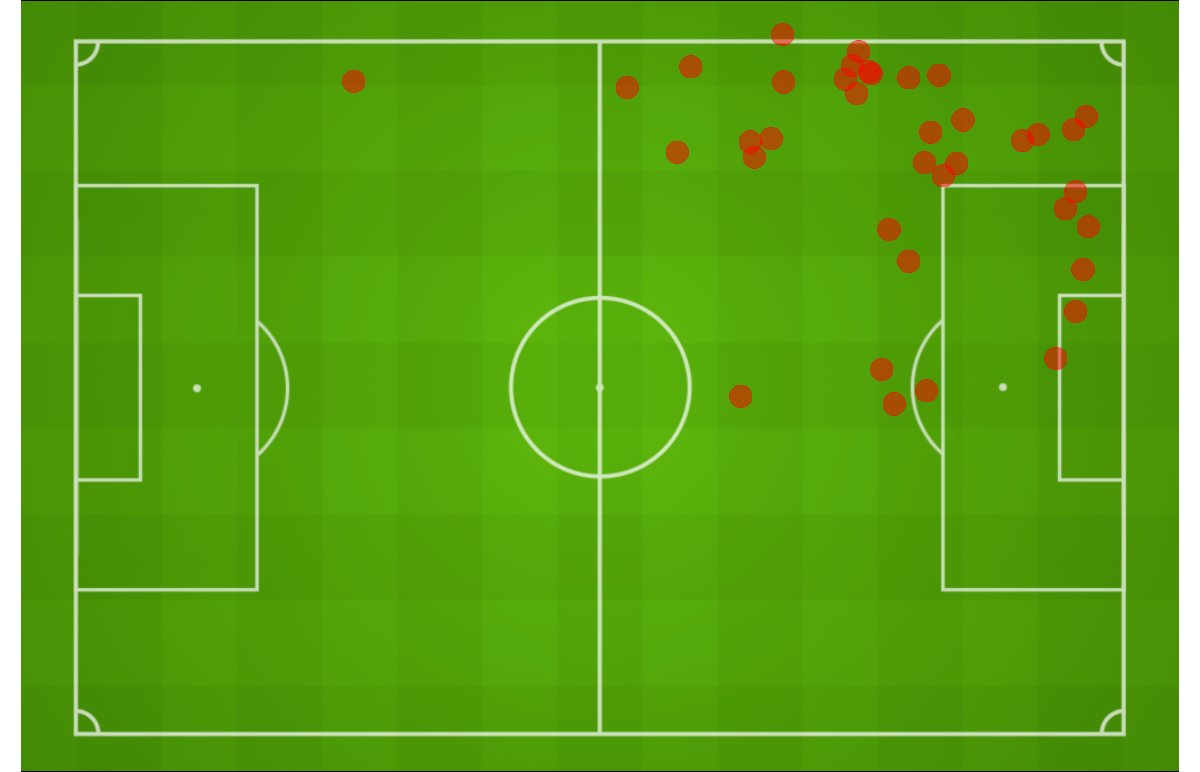

Despite going off in the 68th minute, Coman took as many shots (three) as anyone else on the field. He also had the second-most touches of any Bayern player in the penalty area: six, just behind Robert Lewandowski’s nine. (All data and all graphics come from Stats Perform.) PSG defended deep for much of the game, and Coman’s touch-map shows just how he managed to sneak in. Facilitation down the left flank, and in an era of inside-out wingers -- did you see Angel Di Maria forget about his right foot in the first half? -- he continually got to the byline and then snuck down along it, a tightrope toward the goal. He might’ve earned a penalty in the first half, and then he snuck in at the back post for the winner in the 59th:

|

The assist on that winner came from Flick’s dimmer switch: Joshua Kimmich, whose starting position on the field, midfield or fullback, seemed to determine how exactly Bayern would play. His impact, though, didn’t diminish, no matter where he was. In the title-ish decider against Borussia Dortmund after the re-start, he won the game with a savvy little chip from the right half-space at the top of the box, between where the fullback and center back should be. On Sunday, despite playing a different position, he was right in that same spot, maybe a yard or two deeper. He could have let off a shot -- another chip, perhaps? -- but instead he feigned, stepped on the ball, waited for the defense to shift toward him, and then found Coman on the back post. It was the kind of subtle move only a center-back-at-full-back might make.

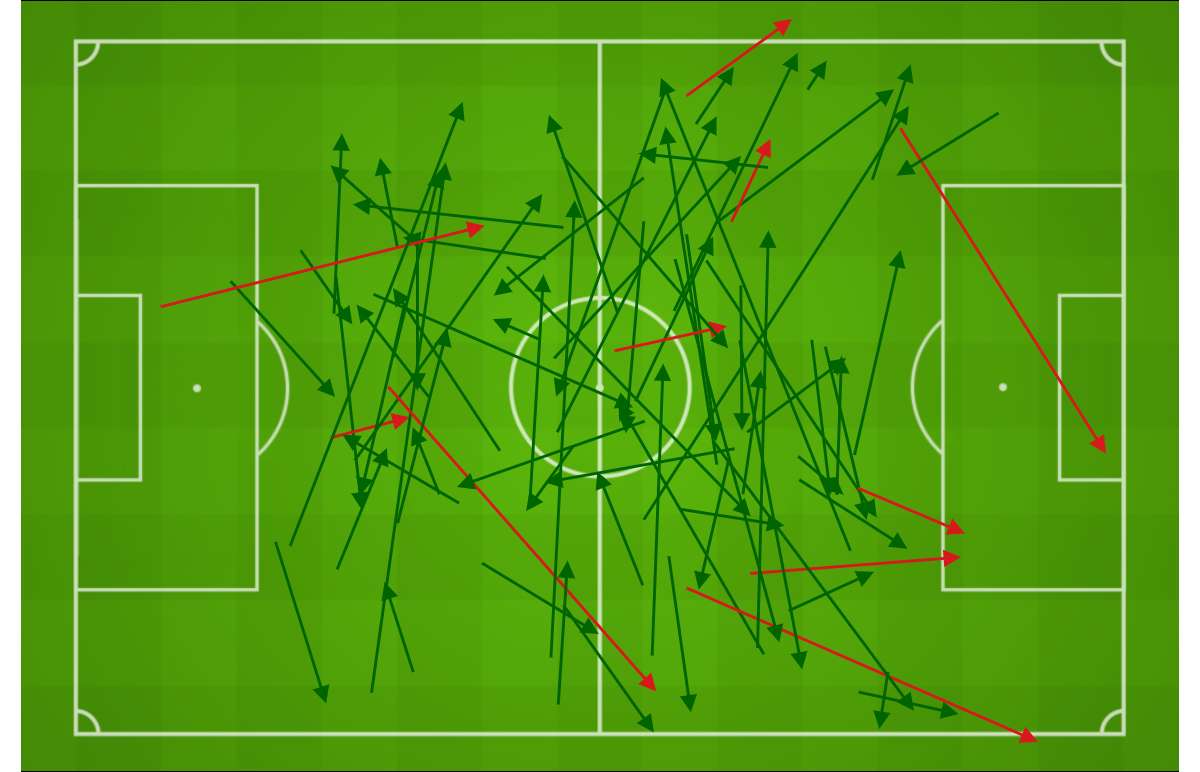

And none of that happens without the multi-line-breaking ball from Thiago up to Kimmich, in what seems like his last game for the club. If Coman represents Bayern’s depth of options and Kimmich is the flexible leader of the club’s new era, then Thiago is the face of the fading old guard. While he took a backseat to Kimmich for much of the post-pandemic restart, he’s been back in the midfield since the Champions League came back. He created as many chances as anyone (two) on Sunday and completed more passes in the final-third (20) than everyone else on the field. The 29-year-old connected on 75 passes in all, 22 more than the next-most-influential passer. He’s the reason Bayern were able to press PSG, deeper and deeper, rendering them unable to mount any sustained attack or a full-90-minutes of sustained defensive perfection.

|

After the first half, it seemed like the patterns were fitting PSG’s preferred model: they didn’t have as much of the ball but Neymar and Mbappe were frequently breaking into a ton of space. The shots and chances were just about even, but PSG had completed nine passes into the penalty area, to Bayern’s one. The scales were tilting one way, despite what the scoreline said. A change in tactics required for Bayern? Nope, they just doubled down on what they were already doing.

In the first half, Bayern completed 67 percent of the final third passes in the game. And they also pressed incredibly aggressively, allowing just 6.71 opponent passes in the attacking half before completing a defensive action. In the second half, their proportion of final-third passes jumped up to 71 and their PPDA got even wilder, dropping to 4.84. They finished the game with a PPDA of 5.6 -- a significantly more aggressive rate than their final opponents, who led Europe with a rate of 7.95 this past season.

Games like this hinge on a couple moments, and this easily could’ve gone the other way. Bayern edged the xG -- 1.54 to 1.07 -- but it was just about even at halftime. Manuel Neuer was imperious in goal after a few down years, though a couple of inches here and there, a Neymar or Mbappe break with a little more spin or a little more placement, and this game finishes differently. But Bayern really did put the clamps down after halftime. With arguably the most talented attack in the world chasing the game against a supposedly fragile defense, PSG could only muster four shots worth 0.45 expected goals.

If it seems like Bayern never lose, it’s, well, because they don’t. The European Cup marked their 21st win in a row. In fact, since a December 7 loss to Borussia Monchengladbach, they’ve won 29 of 30 matches, with the lone blemish coming in a scoreless draw against Champions League semifinalists RB Leipzig, back when they still had their best player. Bayern Munich are, by far, the richest team in Germany, and the eight Bundesliga titles in a row certainly show it. But this? Wrapping up the year with two dropped points from nearly a season’s worth of matches? That wildly exceeds any kind of financial advantage.

And it’s not likely to change any time soon, either. Boateng started the final but went off injured early and was replaced by the 24-year-old Nicklas Sule. Thiago seems like he’s wrapped up his Bayern career in the ultimate fashion, but the 25-year-old Kimmich or the guy who subbed in for him, 26-year-old Corentin Tolisso, can take over that role. David Alaba is 28 and could also be on the move; there’s club-record signing Lucas Hernandez in the wings, ready to go. Both of Bayern’s key attackers this season, Robert Lewandowski and Thomas Muller, are in their 30s and were relatively quiet against PSG -- yet, it didn’t matter at all. Alphonso Davies didn’t break the game in half like he usually does, but he’s still only 19. The electric Leroy Sane is on the way from Manchester City to provide reinforcements, and counting him, the four-most expensively-acquired players on the team didn’t even start the final. The cupboard seems full, even if some of the key figures might continue to change.

Once again, Bayern Munich are the best team in Europe. It’s inarguable. Now, there’s more management to be done, but there’s also the potential for plenty of internal improvement still to come. And after all, can you really question the guy who’s leading the way? We’re still waiting for him to make his first mistake.