|

Black lives matter. This document has an exhaustive list of places you can donate. It’s also got an incredible library of black literature and anti-racist texts. Donate, read, call, and email your representatives. We’re all in this together.

Today’s donation request comes from Peter, who asked for a piece about Olivier Giroud.

It took about five minutes for the Champions League to remind us just how different it is from everything else. The dual-tensions in the Real Madrid–Manchester City and Lyon–Juventus matches almost immediately exceeded anything produced by the past two months of post-pandemic domestic-league soccer. Every single little moment mattered.

Part of that is the nature of knockout soccer; the 38-game season-structure does everything it can to award the inherent quality of a team’s performances, while two-games-and-you-are-gone does quite the opposite. Just about half of the goals scored in the major European leagues contain some visible, obvious amount of luck, and with most knockout ties being decided by a solitary score, watching a Champions League match is a micro-exercise in grappling with the fact that we’re all just a bunch of atoms, bouncing back and forth. What just happened won’t have much to do with what comes next, no matter what you want to think.

And that’s only amplified by how much the unpredictability of the Champions League contrasts with the prevailing forces across the domestic game. The same teams seemingly win every year, and only a couple clubs can even semi-seriously contemplate the possibility of a domestic championship each season. Throw all those favorites together, though, and you get to see all but one of those teams that never lose, well, eventually lose. The quarterfinals start on Wednesday, and the champions of England, Spain, and Italy have already been eliminated.

In fact, five of the last eight champions of Europe were not even champions of their own league. Only Bayern Munich or PSG can save that sample from turning into six of the last nine, but even that’s unlikely, as FiveThirtyEight’s projection model gives them a combined 35-percent chance of winning the whole thing.

The Champions League is a different game because there are so few games; the structure is designed to create drama, not reward performance. But is the game itself, the way the soccer gets played, any different? Are there certain players whose styles are better suited for the high volatility of a two-legged tie vs. the slow-burn of an August-to-May march? Are there teams that are more likely to thrive amidst the short-term madness of top-tier competition rather than week-in-week-out slog of batting aside against inferior opposition?

The statistical output average team across the Big Five domestic leagues isn’t too different from the average Champions League knockout-stage participant. Given how the pandemic-pause potentially skewed things and how few elimination matches have been played so far in this year’s Champions League, I compared the per-game averages of domestic leagues and Champions League knockout matches from last season instead. A couple small things stand out. (All data comes from Stats Perform.) The average domestic team scored 1.37 goals per match, while the average CL team scored 1.57. So, for starters, Champions League knockout matches have about 0.4 more goals per match. Most of that can be accounted for by an increase in shot-quality, as the average number of shots per game per team was 13 in both datasets. CL teams completed a higher percentage of passes (82 to 80), played more passes into the penalty area (13.4 to 12.1), and crossed the ball less frequently as a proportion of total passes (13 percent to 17). Pressing rates and how high the ball was won up the field remained roughly stable between the two competition formats, while the average uninterrupted possession in the Champions League lasted for longer (9 seconds to 8.2), contained slightly more passes (3.5 to 3.2), and moved the ball toward goal at a slower pace (1.35 meters/second to 1.63). None of that is too surprising, though. Better teams tend to score more, move the ball into the box at a high clip, cross less, and produce more measured possessions. Given that those better teams tend to reach the Champions League knockouts, it’s perhaps not a surprise that all those attributes are intensified in the broad trends.

Now, if you’ve followed soccer for long enough, you’ve had the misfortune of being introduced to the term “flat-track bully”. It’s typically employed in the British media and is reserved for players who score a ton of goals but have, at least recently, struggled to score against a specifically and unscientifically chosen subset of teams that will make the aforementioned discrepancy look as bad as possible. Type “[Name] flat-track bully” into a search engine, and you’ll be able to find results for just about every great goal-scorer of the modern era. You, of course, would expect all players to score fewer goals against more difficult competition. And on top of that, research into the topic suggests that there’s typically no real year-on-year correlation between the types of teams a player scores his domestic-league goals against. Hence, every player falls into the “flat-track bully” data-fit at some point. It’s small-sample size confusion, or the result of looking at the wrong things, or both.

With its consistently high level of competition, the Champions League is fertile ground for declarations of even-surface bullydom. Here’s an example, from 2015:

|

Five years later, that would seem to remain true. Since 2010-11, Giroud’s rate of non-penalty goals per 90 minutes in domestic play is 0.51, while in the Champions League it drops to 0.4. That’s a 21 percent decrease, and among the 45 highest goal-scorers this decade (who have also played significant CL minutes), that’s one of the largest negative discrepancies.

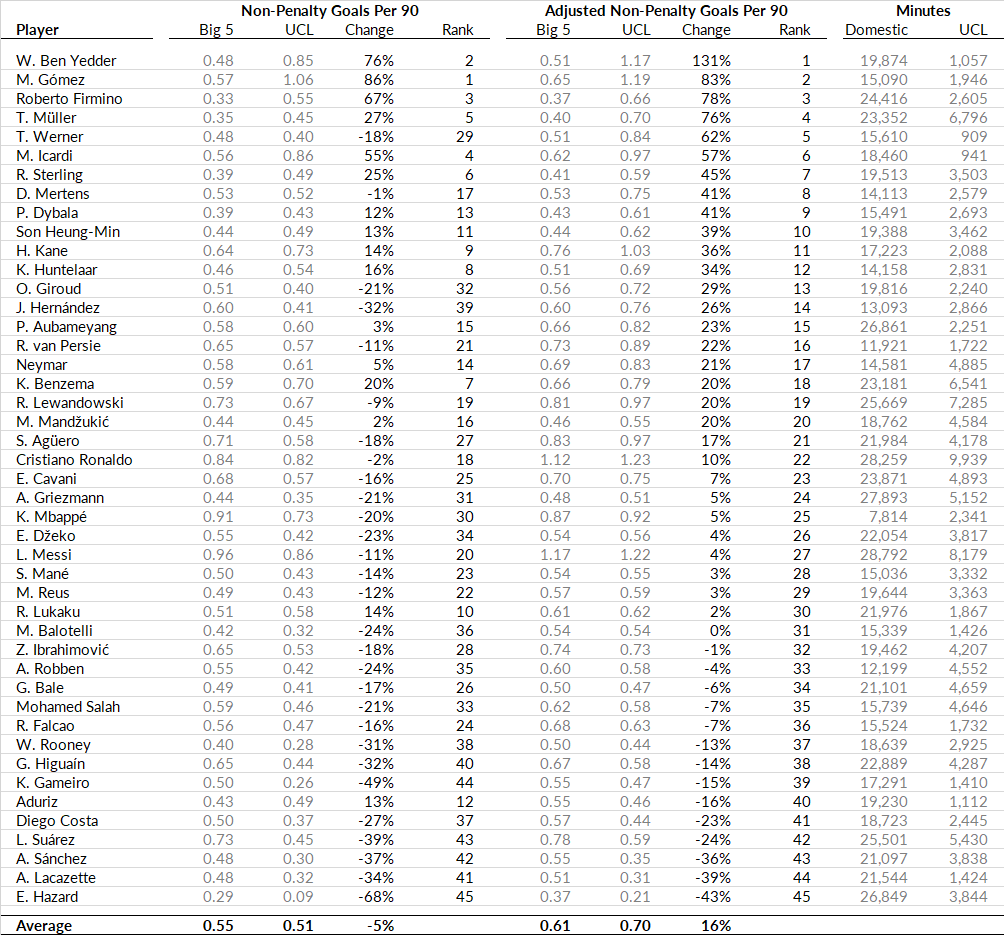

Except, that’s not quite right, according to research from the consultancy 21st Club. Using their World Super League rating system, they can standardize for the quality of the opponent that a player has scored his goals against. In other words, a goal against Atletico Madrid is worth more than a goal against Aston Villa. Using that info, they then figured out what a player’s scoring rate would be in both the Champions League and domestically had he played all of his games against an average Big Five team.

“When we account for the fact that Giroud’s UCL goals have come against Bayern Munich, Napoli, Dortmund and Monaco, we actually estimate that his scoring rate in the UCL is better than in domestic competitions, given the tougher quality of opponents faced,” said Omar Chaudhuri, chief intelligence officer at 21st Club. “Giroud is an example where his drop off in the UCL makes him look like a worse UCL player than what he is -- reflected by the fact that his 'change' in NPG90 is ranked 32 on the list, but he's 13th on the adjusted rates.”

Here’s that list Omar referred to:

|

There are some interesting individual stories. Monaco’s Wissam Ben Yedder is apparently the Robert Horry of soccer, for starters. Despite all the consternation surrounding his lack of goal-scoring this season, Liverpool’s Roberto Firmino has scored bigger goals than either Sadio Mane or Mohamed Salah. The most volatile player of the past 10 years, Mario Balotelli, is also the most consistent; it doesn’t matter who he’s playing. And although Cristiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi have both scored at lower rates in Europe than domestically, when accounting for competition, they’ve both actually stepped it up in the CL.

The two best players of their era, then, highlight the more intriguing general trend. The 45 most-prolific goal scorers of the past decade saw their goal-scoring dip when they jumped from domestic to continental competition: 0.55 NPG per 90 down to 0.51, a five-percent decrease. But when you account for the quality of competition, the best goal-scorers in Europe have actually increased their scoring rates, on average, in the CL when compared to their domestic leagues: 0.61 adjusted NPG per 90 up to 0.70 NP goals, a 16-percent increase.

“These players score more goals in the UCL than they do in their domestic competitions, after accounting for the tougher opponents,” Chaudhuri said. “It does seem that these elite players have an extra ability to switch it on in the biggest competition.”

Two names stand out among the eight teams left: Raheem Sterling and Thomas Muller. The former has scored at a 45-percent higher opponent-adjusted rate in Europe, while the latter has been 75-percent better. They, of course, both play for the current betting favorites (according to the Fanduel sports book), with Manchester City at +200 and Bayern Munich not far behind at +300 to win the whole thing. Per FBRef, Bayern and City produced the two-best expected-goal differentials in Europe by far -- among teams that are not as resource-advantaged Paris Saint-Germain -- and they each have star players with a long track record of performing even better when the game goes outside their borders.

Seems like a pretty good recipe to win the whole thing, huh? City and Bayern are near-perfect teams in just about every way-- dominate possession and territory, score a crazy amount of goals and concede relatively few -- except for one thing. Back before play paused, I looked at the profiles of the previous eight winners of the tournament to see which current sides fit the statistical billing. They all -- even the Chelsea team that finished sixth in the Premier League but somehow won the European Cup -- scored an above-average number of goals and conceded a below-average number of goals. They all took an above-average number of shots and conceded a below-average number. They all averaged a relatively high amount of seconds-per-possession. Again, mostly: duh. But the one standout factor was that all the Champions League winners held their opponents to average or below-average shots. That’s not a characteristic shared by all top teams -- you can concede a championship-winning number of goals by conceding a few HQ chances each match -- and this year both City and Bayern have allowed an xG-per-shot value that’s above the Europe-wide average.

The one major way the Champions League differs from domestic play is in the dynamics of superiority. Unlike the other major sports, there are no downs, no innings, no shot clock to ensure a roughly equal amount of scoring opportunities to both teams. Given the game-to-game randomness of the sport, almost all of the top teams in Europe now try to dominate territory, dominate the number of chances, and score a ton of goals. Sure, sometimes the shots don’t go in or you get hit by a couple precise counter-attacks, and then you lose a game you weren’t supposed to. But that’s the best way to attempt to ensure success over a 38-game season. The top teams in the world attack more aggressively than ever before.

In the Champions League, though, the best teams play the best teams, and while there is the rare side that can just port its dominance over Betis to dominance over Bayern Munich -- see: FC Barcelona, 2014-15 -- most of the sides will suddenly face extended spells without the ball. At home, a City or a Bayern can afford to be less-than-great at final-third defending because they rarely have to defend their own final-third. But then that all changes when, well, they have to play each other. You’d think this might tend to favor smaller teams, who might be more adept at wringing results out of a lower-possession approach, but the small teams that make the Champions League every year are still the big teams in their own domestic leagues.

“Teams in smaller leagues struggle in the UCL -- not just because they tend to be weaker, but because they need to play open, attacking football in order to win their leagues, but then need to hunker down in the UCL; a change of style that isn't easy to do,” Chaudhuri said.

And so there’s one team that’s come close to threading the needle over the past decade -- a side that’s consistently brilliant defensively but is also capable of scoring just enough goals to ensure that they qualify for the Champions League every season. That’s Diego Simeone’s Atletico Madrid. They’re the only team remaining that averaged less than 50 percent possession this season. They allow the lowest-quality shots of any team in Europe -- 0.08 xG per shot -- and they’re almost impossible to catch off guard, as just two percent of the xG they’ve conceded this season has come from fast-breaks, which is the second-lowest number in all of Europe.

They don’t fit most of those characteristics of past winners. Most notably, they, uh, can’t score -- just 1.34 goals per game, while the European average is 1.40 -- but with the quarterfinals and semifinals both moving to one game rather than two, all they need is to catch some finishing lightning in a bottle for three total games. They’ve already knocked off Liverpool, the defending champs, and Diego Simeone still has yet to be eliminated from the tournament by a team that didn’t employ Cristiano Ronaldo. Atletico drew the easier side of the bracket without City or Bayern, their quarter-final opponents, RB Leipzig, lost their best player to Chelsea, and oh yeah. Ronaldo? He’s already gone home.