|

|

Happy Sunday. I am sitting by the window in New York City, listening to I am by Jorja Smith that is playing sometime in your past, which is also my present, thinking about the passing of Chadwick Boseman and how life is so damn short.

What we share is Fakepixels, a space for honest inquiry and bold ideas. Here, we are not afraid to ask bold questions and find invisible forces that challenge the status quo.

|

It's now a daily occurrence that someone calls me and tells me they are leaving somewhere or starting something. I said goodbye without hugs, and sent congratulations without celebrations.

Renting a cottage in Dubrovnik to tackle NLP, starting a consumer brand that sells CBD-infused candies, quitting a glamorous career in pursuit of the childhood dream of becoming a novelist in the wild west, leaving the power center to go on a solo trip to meet with Internet friends across the country, everybody follows traces of certainty and everybody on the road. The ambition of young people that still have so much to prove starts manifesting through fast iterations. We seem to be collectively awakening into a moment of clarity, recognizing the absurdity of the existing measures of success.

I can’t help but think of the book “Measure What Matters” by John Doerr, the holy grail of a concept that gave birth to multiple heated startups in Silicon Valley. It seems like “what matters” has changed. It’s not that what used to matter no longer does, but what used to matter is not the only thing that matters.

When a metric is picked as a proxy of competence, it inexorably ceases to be a useful measure because people start to game it. This idea stirred my meditation around Goodhart’s Law — a concept proposed by Charles Goodhart, a chief economic advisor to the Bank of England, and more commonly known as the business adage: “the worst thing that can happen to you is to meet your targets.”

Take a country that wants to grow its GDP at the expense of environmental and individual wellbeing, a firm that fudges its numbers on quarterly earnings reports, or a high-school student who spends all her time gaming the SAT score. In the above cases, whether the country has actually become more prosperous, the company more valuable, and the student more analytical remains obscure.

This doesn’t mean that the old metrics are necessarily wrong, but they are certainly incomplete. We still need metrics. Without them, progress can’t be made productively. The spirit of the metrics-driven approach dominating the American narrative is embodied by this quote by H. James Harrington: “measurement is the first step that leads to control and eventually to improvement. If you can’t measure something, you can’t understand it. If you can’t understand it, you can’t control it. If you can’t control it, you can’t improve it.”

In an attempt to find mitigations to this paradox, writer Blogospheroid on the rationalist blog LessWong breaks down a scenario of Goodhart’s law:

Superiors want an undefined goal, G.

They formulate G*, which is not G, but until now in usual practice, G and G* have correlated.

Subordinates are given the target G*.

The well-intentioned subordinate may recognize G and suggest G** as a substitute, but such people are relatively few and far between. Most people try to achieve G*.

As time goes on, every means of achieving G* is sought.

Remember that G* was formulated because it is simple and more explicit than G. Hence, the persons, processes, and organizations which aim at maximizing G* achieve competitive advantage over those trying to juggle both G* and G.

P(G|G*) reduces with time, and after a point, the correlation completely breaks down.

He proposes three methods of mitigation:

Hansonian Cynicism: pointing out what most people would have in mind as G and showing that institutions all around are not following G, but their own convoluted G*s (e.g., people expect universities to be about education and hospitals to be about health).

Better Measures: taking multiple factors into consideration, including a complete map of human morality, irrationality, and incentive. If G is defined fully, there is no need for a G*.

Solutions centered around Human Discretion: continually checking and rechecking that G and G* match through human discretion on a case-by-case basis.

The first mitigation is not really applicable beyond initiating the conversation, and the last one is not scalable. The second approach seems to be the most promising and has been validated by the emergent properties of open-source software or product-led growth: decentralized decision-making and participation, qualitative measures for progress, and generosity towards mistakes with layers of redundancy.

The mind shift from an almost dogmatic attachment to metrics and measurability is uncomfortable because it requires venturing into randomness, serendipity, and uncertainty, the areas that can only be extrapolated but never perfectly modeled.

From a data science perspective, oftentimes, we use mean-squared error for regression or F1 score for classification problems to measure the accuracy of an ML model. Knowing the detrimental consequences of using only a single measure, we might also consider interpretability and usability so people can better understand and collaborate on the models.

From a UX design perspective, oftentimes, we use one metric to measure efficacy, such as conversion, DAU, or session length. We might also consider going into the field and get on a call with the customer and acquire qualitative data and build personal relationships to contextualize anomalies.

From a venture investing perspective, we can be tempted by top-line growth or ownership or price, without taking into consideration the dreamers’ beautifully irrational motivation.

From a self-development perspective, when we use one metric to measure success, such as impact (a gen-z problem), we become vulnerable to disillusionment and cynicism.

This ongoing musing helps me land in an uplifting place.

It’s not that what used to matter no longer does. It’s more precise to say that there are new opportunities to measure what didn’t get measured before, and through the crisis, we arrive at the dawn of this refreshing revelation.

Faith in the machine

|

India’s spiritual market is said to be valued at between $30 billion. Though this number is likely inflated, it’s not far off when taking country’s 200 million Muslims and 28 million Christians into consideration. Technology and religion are circling closer than ever before.

VR Devotee is a chance for people who can’t get to temple to still do darshan with their home gods. The user is transported to the midst of a Hare Krishna temple, wherein hundreds of thousands of flower petals were raining down over the deity.

Though the app was launched back in 2016, but the momentum really kicked off when the pandemic arrived. By February 2020, the service had been accessed more than 90 million times, and the amount of time people are spending on the app is skyrocketing. While VR Devotee boasts the world’s largest repository of temple footage, the firm itself was just 13 employees, and although the user growth isn’t insignificant, it’s still only in the early innings of a huge, and important market.

The haunted link, sent via Zoom

|

Every generation has its dark places.

The movie Host decided to insert takes the Zoomers to a place too familiar to all of us. The film is made remotely over 12 weeks during lockdown over Zoom. Though it uses supernatural horror tropes — like some spicy jump scares — the film is able to immerse the audience by locating them in the same setting with the subject, through the screen.

From ballads to theater to genre fiction to film to gaming, the evolution of storytelling throughout history is enabled by technology’s unique capability of granting power to the audience. Informed by data, content production has evolved to a point that media serves to turn the audience’s internal fantasy inside-out. One of these fantasies is precisely the horror that would at some point emerge from the never-ending Zoom calls.

The most fascinating part about creating a film that is based on a piece of software is that it challenges the illusion of human agency over the tools that they created. We feel fear when we’ve presented the constraints of our own agency, and we' feel empowered when such constraints are removed. The most engaging content oscillates above and below this constraint, and technology is making turning the dial so much easier. Everyone can be a part of it.

Anti-authoritarian Telegram journalism

|

Sergei Gapon/AFP via Getty Images

Telegram has become an indispensable tool in coordinating the unprecedented mass protests that have rocked Belarus, when Alexander Lukashenko, the man often referred to as “Europe’s last dictator,” receive 80% of what was believed to be a rigged vote.

The Telegram NEXTA_live now has over 2 million subscribers, the equivalent of 1/5 of the entire population of Belarus. Behind the movement is the 22-year-old Stepan Putilo, a student of film and video production at the Silesian University of Technology, in Poland. He hasn’t been to Belarus since 2018 when authorities attempted to open a criminal case against him for insulting the president on social media. That same year, He launched the Telegram channel, and 2 years later, turned it into a news media.

Necessity not only spurred innovation but more importantly adoption of innovation. Over the two-day-election, connectivity in Belarus was reduced to 20% of normal levels, and all social media sites were shut down besides Telegram.

This is not the first time that the non-profit organization with a focus on encryption and a vision for ultimate decentralization mobilizes mass movement. The messaging app became one of Hong Kong’s most downloaded apps last summer, as hundreds of thousands protested against Hong Kong’s proposed extradition bill with China.

|

Getty Image

Last October, the SEC ordered Telegram to halt sales of its cryptocurrency Gram after it failed to register an early sale of $1.7 billion in tokens prior to launching the network. The funds were raised in a series of what Telegram billed as pre-ICO offerings back in 2018, though the company ended up canceling the much-hyped ICO due (in part) to increased SEC scrutiny.

Founder and CEO of Telegram Durov spoke out against the ruling in his announcement, arguing that American courts shouldn’t have the power to stop the sale of cryptocurrency beyond US borders:

This battle may well be the most important battle of our generation. We hope that you succeed where we have failed.

|

Proctor and Gamble reported an organic sales increase of 6% YoY as COVID boosted consumer demand for products in its healthcare, fabricate, and homecare categories. For the fiscal year ended June 30, the Cincinnati-based consumer products giant reported a $17.1 billion profit on $67.7 billion in sales.

Newcomers have tried to challenge the giant in the past decade, but the company continues to thrive. Despite its quirky advertising, P&G is known for being disciplined. Their guiding philosophy is to plan thoroughly, minimize risk, and stick to their proven principles.

How does that manifest in practice?

As early as 1977, their Chairman introduced the idea of Beta Access:

The largest part of our initial investment is usually in the form of introductory sampling.…Only when satisfied customers have had firsthand experience with the product will the elements of the marketing mix, such as advertising and selling, be fully productive.

They never enter small categories unless they expect them to grow, and they set out to dominate every category they enter. And by building huge volume, they achieve lower manufacturing costs than their competitors, and this gives them higher profit margins or permits them to sell at a lower price.

They use market research to identify consumer needs. Said Ed Harness, their former Chairman:

We are forever trying to see what lies around the corner.… We study the consumer and try to identify new trends in tastes, needs, environment, and living habits.

|

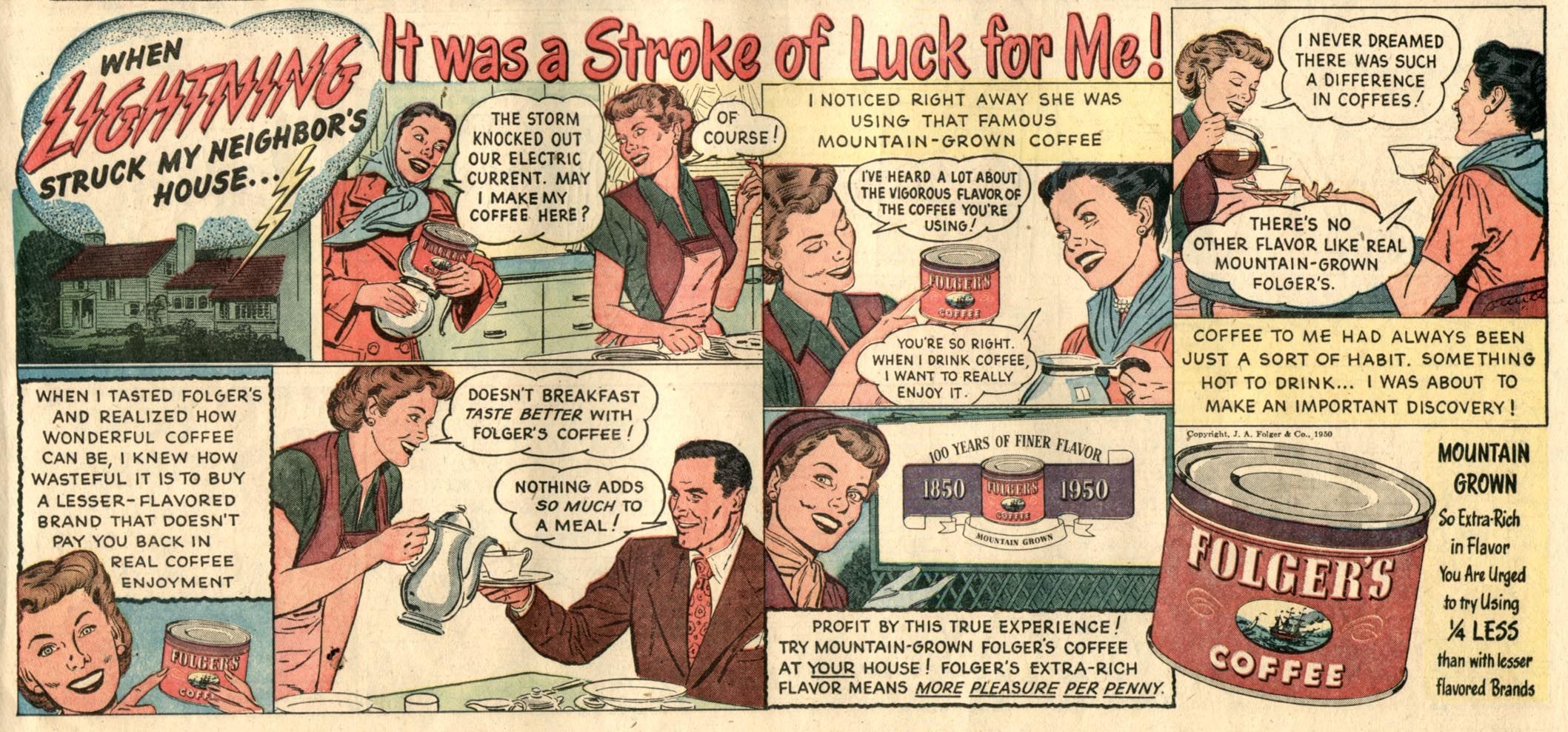

Most important of all, they have a way of creating superior products that blow their competitors out of the water through their blind in-home tests. The test-marketing is usually unbelievably thorough and patient. They tested Folger’s regional expansion program for six years before moving into the East.

“Patience is one of the virtues of this company,” the president shared.

They would rather be right than first. Only three products in the history of P&G have gone national without being test-marketed for at least six months. Two of them failed.

For advertising and marketing, they believe the first duty is to communicate effectively, not to be original or entertaining, and they measure communication at three stages: (1) before the copy is written; (2) after the commercials are produced; and (3) in test markets.

|

All their commercials include a moment of confirmation. They show a woman squeezing the Charmin and attesting to its softness. They show a housewife observing that Era gets out grease spots. In 60% of their commercials, they use demonstrations, showing how Bounty absorbs more liquid, how Top Job cleans better than straight ammonia, how Zest leaves no film, all to show the value prop clearly and directly.

Software has largely increased the feedback loop from customers, but how much have we progressed to create a product experience that is truly disciplined around thorough research and testing? Consumerization of software doesn’t just mean that software is becoming more UX-friendly like a consumer-facing product, there are industries where the software needs to built with the same level of clarity, patience, and discipline, where being agile isn’t enough.

|

Lou Stovall | Midnight Journey (2011)

Eric Gilbert, Associate Professor in the School of Information at U Michigan, open sourced his syllabus for his phD students.

He acknowledges that the phD programs are largely relationship-driven and lack specificity to measure success. The goal of this document is to help his student succeed. The sincerity and authenticity are palpable. I find most sections of this document quite universal and can be applied to not just the field of academia but any career paths that share similar characteristics:

You don’t get immediate gratification and the feedback loop to know if you are any good is long

You need to take many bets, but the upside can be infinite

You have meaningful freedom and agency, but very little handholding and manual of success

You need to hustle, but hard work is necessary but not sufficient

You want to study deeply what has been done, but true reward comes from discovering a path what hasn’t been tread

Gilbert’s document created both the mind frames and the quantitative benchmark to mitigate the fear of navigating in obscurity. For example, on picking an area to work on, he suggests a series of questions that lead to impactful work:

What difference will this work make if you succeed?

Whose lives will be made better by this research?

How will this improve upon what’s currently being done?

Why is this one of the most important questions in the field?

Will it create a big policy change at some level (company, government)?

Will it inspire a new class of systems?

He advocates for quality over quantity, a difficult practice to abide by for a restless young person:

I hate that I have to write this down. I would like it if you could only focus on super important problems, and obsess about their solutions. I only do it because I see a lot of anxiety among students about whether they will have the CV necessary to get a good job in the end.

Yet he’s not blind to the realities of the market that rewards sheer quantity, so he found a balanced strategy where his students can graduate with “3-4 core, high-risk, high-reward publications; 2-4 lower-risk, straightforward papers; and, 3-4 supporting role papers” in the span of 6 to 8 years.

His proposal gives me this idea that given a time constraint, there’s an optimal strategy for project creation that maximizes return and minimizes risk. For example, I can ambitiously pursue 4-5 projects that are high-risk, high-reward, 2-3 projects that are lower-risk, cookie-cutter, and 1-2 other supporting projects in this stage of my career. This is a more aggressive portfolio, and the composition of risk might evolve as I grow older, but I kind of don’t want that to happen just yet.

Like investing in public stocks, you’d come close to achieve optimal diversity when you add the twentieth stock to your portfolio. But when you over-diversify, losing the potential of big gainers will also significantly impact the overall return, a.k.a. “being spread too thin.” The outsized return comes from the asymmetrical information about a new idea that others might not pay attention to, and this strategic advantage is most natural when it comes from a place of obsession and curiosity.

He gives some concrete ways where he seems to come across new ideas.

As technologists, we are very close to people in industry doing similar things. I try to keep up on what’s happening in industry. Often, I find myself asking: Why are they doing it this way? What would I do differently, especially since I’m not bound by earnings reports? What are they overlooking? These are often interesting places for an academic technologist to ask questions and think about new projects.

I recommend giving the whole thing a read.

|

🎲 Fiction: What should we talk about with our AI overlord

And yet, we know the AI must be watching, and it brings us great shame. It's judging us silently, thinking we’re fools for squandering our time.

We force ourselves to forget it ever existed

— Written by GPT-3 via Sudowrite

Science fiction writer James Yu created Sudowrite, a writing engine powered by GPT-3, to create this thrilling and chilling story. Increasingly so, I find myself in the camp of believing that AI can unleash our creativity by helping us see realities through not only a cause-effect lens, but through unexpected randomness.

🤖 Essay: Impact of AI on a lifelong pursuit

The term “divine move” is used as a metaphor for an ultimate level of play. With AI, however, we all realized that the best way to reach the highest possible level of Go is not through thinking about it for a lifetime.

What it means when AI takes away a man’s purpose for life. A meditation.

📄 Paper: theories on Serendipity

There are four types of serendipity, or happy accidents in research:

1) Discovery of something you weren’t looking for

2) Solving a different problem than expected

3) Unfocused work leads to epiphany

4) Unfocused work leads to discovery of a whole new space

The main contribution of this paper has been to develop a typology of serendipity in research and to identify the main mechanisms through which it occurs. The mechanisms suggest that serendipity is not random, there may be important factors affecting its occurrence, and there may even be scope for altering its prevalence.

Fakepixels is a space for courageous thoughts.

We believe in the power of deep thinking, nuanced dialogue, and creative courage. By being present with the world and with each other, by learning relentlessly, and by bridging knowledge across realities.

We’re here to dream and agitate and question openly and unapologetically. We’re here to be vulnerable, honest, and true. If you are interested in contributing, I would love to have you join the club.

I’m taking my time to get to know each of you, and I do this on nights and weekends. Appreciate your patience in advance. Until then, why don’t you bring a friend?