|

Black lives matter. This document has an exhaustive list of places you can donate. It’s also got an incredible library of black literature and anti-racist texts. Donate, read, call, and email your representatives. We’re all in this together.

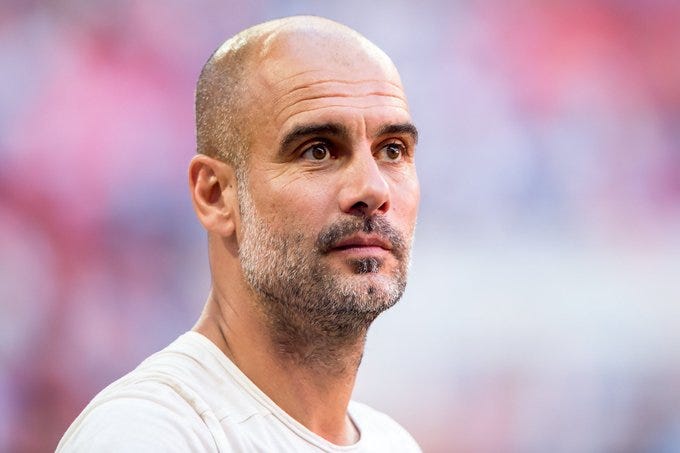

Modern soccer was born when a monkish eccentric in Catalonia decided to redraw the map.

For a while, the field as commonly conceived had three zones. Although teams could stagger players in any number of vertically arranged lines, there wasn’t any real diversity of classification when it came to describing how your team aligned itself horizontally. You had your wide-right players, you had your wide-left players, and you had your central players.

The former Barcelona, Netherlands, and Manchester United manager Louis Van Gaal was perhaps the dominant obsessive-compulsive, systems-oriented coach of this specific previous era. He divvied his players’ responsibilities up by slashing the field into 18 rectangles. There were six horizontal lines, but only three ran vertically. Essentially, you had the central zone, which extended from the vertical edges of both penalty areas and off into outer space, infinitely in both directions. Then, on the outside of those lines you had the left and right wings, bordered by the sidelines.

Within this geometry, the most important area of the field became the rectangle that sat atop the penalty area. Multiple studies found that the teams who won most often were the teams that played the most passes into this zone and the most passes from this zone. And the defining sides of this era all had players who flourished in this particular space: Zinedine Zidane for France, one of Andy Cole or Dwight Yorke as part of Manchester United’s striker pairing, and Dennis Bergkamp for Arsenal’s Invincibles.

How did managers solve against that? Easy, just pack more players into the rectangle. In response, coaches like Jose Mourinho and Rafa Benitez rose to prominence by building structurally sound sides that seemed to prioritize defensive shape over any kind of proactive attacking play. They filled the zone not only with more bodies, but with dynamic, aggressive ball-winners who would never allow Bergkamp the kind of space or time you saw in the video above.

For a little bit, it seemed like these guys had solved the game. If you couldn’t create from the central zone, then what could you do? You couldn’t sit back and counter against these teams because that’s what they were doing, and they were better at it than you’d ever be. Sure, you could try to work some space down the wings, but crossing was an inefficient strategy on the whole, and it was especially low-value against the kind of physical defenders these coaches built their teams around. The only way to beat a Rafa- or Mourinho-type team, it seemed, was to try to play the same way, but just do it with more talented players.

And so, what can be done in the face of a seemingly inevitable trend? As anyone who’s paid any attention to the dislocation of American society over the past decade knows, you move the lines. Pep Guardiola would no doubt hate that comparison, but that’s what he — and others, including current Liverpool manager Jurgen Klopp — did. Rather than limiting themselves to three zones across the field, Pep’s teams roughly organized themselves into five horizontal zones: there were the two wings (same as they were before) and then they split that original central zone into three smaller ones. And although the most-central zone was still the prime real-estate, his Barcelona, Bayern Munich, and Manchester City teams all dominated from the right- and left-centers, or as it’s become known: the “half-spaces”.

As Rene Maric, now an assistant at Borussia Monchengladbach and one of the hottest coaching prospects in Europe, wrote in his comprehensive theoretical breakdown of the half-spaces:

FC Barcelona played from 2008-09 to 2010-11 with a front three that deliberately focused on the half-spaces and the “intermediate positions” in those zones. This was especially the case in their two successful Champions League seasons. [Thierry] Henry and [Lionel] Messi (or Eto’o) and [David] Villa and Pedro moved from a wide position into the opposing channels. The three of them were able to bind four players while the wings were used by the advancing full-backs.

Thierry Henry put it a little more vividly:

Just from you being high and wide, and then coming back in, you are actually freezing four players because we are threatening to go in behind. With Eto'o and me running in behind, and Xavi and (Andres) Iniesta on the ball, with (Lionel) Messi dropping, either you die, or you die.

Like so many innovations in sports, the logic is obvious in hindsight. The half-space occupies the area to the side of where the defending team’s central midfielders were positioning themselves. And then, looking forward, it’s also the area in between the fullback and the center back. It’s where the most dangerous, available room was, and it forced fullbacks and center backs to constantly make decisions about who would pick up the player in the half-space. On top of the spatial advantages, the half-spaces let you easily play a pass into the central-most zone, the half-space you’re in, or the wing. No other spot on the field allows that kind of immediate access to that many different zones.

At Bayern, Guardiola’s team continued to exploit this area by having their fullbacks pinch into the half-space zone rather than hug the space out wide, while at City you’ll now frequently see the team with five or six players all pushed into the forward line, accessing all of the gaps in the opposing back line, depending on whether it’s a back three or four. You’ve seen the goal so many times now: through ball between the fullback and center back, cut-back, tap-in to an empty goal.

Enough time has passed, however, that idea of the half-space is no longer some avant-garde spatial re-imagining; it’s now closer to an established best practice. In 2018, the Welsh Football Association, not what you’d call the bleeding edge of tactical experimentation, had devoted multiple sessions of its high-level coaching course to the concept. “We did a two-day contact about the half-space”, said Steve Sidwell, a midfielder who played for Jose Mourinho at Chelsea. “Guardiola has it locked down.”

That’s true -- until you look at his defense.

On Sunday against Leicester City, Manchester City looked just about as wobbly as they ever have under Guardiola. They lost 5-2, and by Stats Perform’s expected-goals data, it was the second-worst game they’ve played under Pep. All five Leicester goals came through the half-spaces:

This pass leads to a penalty:

|

This pass gets played into the box and leads to a cross that leads to a goal:

|

This pass leads to another penalty:

|

This shot ... somehow goes in, and you can live with that as a defense, but the only reason the shot happens in the first place is the lack of pressure in the half-space:

|

And this pass, you guessed it, leads to another penalty:

|

Three penalties and a barely-scientifically-plausible long-range goal might seem like a one-off thing -- especially against a spot-kick-drawing wizard like Jamie Vardy -- but Guardiola certainly doesn’t think so. “I am not going to give up,” he said after the match. “I am going to try to find solutions”.

Despite last season’s struggles, City came into this year as the betting favorites for the fourth season in a row. They still, you know, scored 102 goals, had the best goal differential in the league by far, and also sported the best defense in the league by expected goals. But something did change.

In the two title-winning seasons, City allowed 6.26 shots per match. That overly precise number didn’t budge from one year to the next. Last season, that number jumped up to 7.37. Not a huge change -- until you consider that the XG per shot allowed jumped from around 0.106 to 1.37. From one season to another, they basically went from a team that was conceding the lowest-quality shots in the league to a team that was conceding the highest-quality shots in the league. Toss in that extra shot, and they went from allowing 0.68 xG per game to 1.01. While that was still the best number in the league, it also masks how frail the defense actually is.

Perhaps in response to all this, City played slower and more deliberately than they ever have under Pep last season. And yet, despite averaging the fewest per-game possessions of the Guardiola era -- 85, compared to an average of 90 -- City conceded the most xG. When the other team has the ball, City are way more vulnerable than they ever have been before. And much of that vulnerability comes from passes between those gaps in the defense. As James Yorke wrote in his preview of Manchester City’s season for Statsbomb: “Across 2017-18 and 2018-19 City gave up 21 shots from throughballs and three goals. In 2019-20 alone they allowed the same volume of shots against (21) but this time gave up seven goals.”

Despite all of that, City still performed at a title-winning level last season. That league-leading plus-67 goal differential was the fourth-best mark in the history of the Premier League. Plus, City still have so much of the ball that it limits the overall effect of even the weakest defensive frailty. But while in previous seasons any City defeat seemed to require an act of god, that is no longer the case. Of City’s five-worst performances under Pep (based on xG differential), all five have happened within the past year.

The volatility and vulnerability has become such a worry for Guardiola that, as John Muller outlined last week, City have started playing with the very structure -- a deep, two-man defensive midfield -- that Pep has built his entire career around defeating. The map that he drew is now helping his opponents plot his demise. Can City find some new lines to add to their defensive third? Because Thierry Henry’s words have increasingly rung true for the other team. When City’s opponents have the ball, you die, or you die.