Takeaways

Investing early in others is not just kinder but also the smarter thing to do

Poor people play the lottery despite negative expected value, because there's more to life than expected values

Feature post by Brett Bivens on how progress depends on storytelling and the evolution of who is empowered to be a storyteller

There’s a 7 question reader survey this month, please take 3 min to fill it up when you have the time!

1. Invest early in others

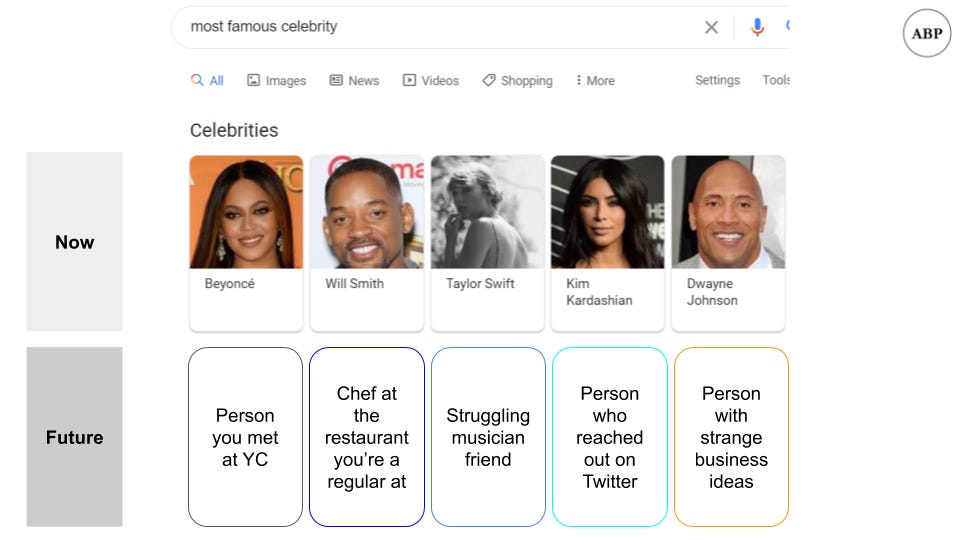

Suppose you had to get a meeting with Beyonce [1].

How would you do it?

One way would be to find the most connected person you knew, and then asking them if they knew any mutual acquaintances. Keep repeating that process.

Another would be to try and raise enough money to book her for a private performance.

Yet another would be to try to get viral with some tweet or video and hope she notices.

These are all plausible options, mostly with a low chance of success.

Now suppose you were Beyonce's first producer, manager, or even songwriting collaborator [2]. How much easier do you think it would be to get that meeting?

Here's a common desire we all have - We want to know famous people.

We want to meet them, we want to be them, we want to tell others about how our good friend Taylor was rudely upstaged by our other friend Kanye who was defending our best friend Beyonce

That in itself isn't that big of a problem. Heroes are a big part of any society, and some admiration is understandable.

Here's what is a problem - We want to know famous people, but only after they've become famous.

Drug addict actor? Leave him out of the limelight till he becomes too big to ignore

Chef with cancer? Nah, let's wait till he wins Michelin Stars before we see him

We know that it's implausible, but we have some bizarre hope we'll just run into Neil Gaiman on the street and instantly become best buds after talking about how big a fan we are. We can't help but to dream. Dream and desire.

The alternative approach then, is to get to know famous people before they've become famous.

This sounds impossible. If we could predict the future that well we'd be off in Switzerland skiing with Scarlett Johansson.

But there are people that already do this. And while they can't guarantee that all the people they know will succeed, they can guarantee they'll have a much higher chance of knowing a successful person, mainly due to their mentality shift.

The simple, but not easy, solution, is to invest in others early. Invest as much as you can - time, money, advice. Invest in as many people as you can. Invest as often as you can.

Those familiar with finance might find it helpful to view this from an options point of view. For those unfamiliar, think of lottery tickets.

If you wanted to win the lottery, how many tickets should you buy? The more the better, but it also depends on how much you're buying them at. If the tickets were nearly free and the prize is large, you'd be grabbing as many opportunities as you could.

You can see examples of people benefiting from this in finance, tech, and life.

On the finance side, Y Combinator and all other accelerators have this mentality. Take small (for YC) stakes in plenty of companies, and then benefit when any one of them succeeds. Similar factor for why angel investing is becoming so popular

On the tech side, warms intros and coffee chats are the default way of building social capital. People recognise potential, and organise themselves for optionality in others.

And on the life side, everyone has this eccentric uncle that somehow seems to know everyone important in the empire [3].

|

What all these people realise is the simple truth that on average, things go up over time. Fortune, fame, favour - these compound over time for most. Even if you don't like helping people out of kindness, helping people selfishly because you believe they'll be successful also makes sense.

Note that I'm not saying everyone succeeds, just that on average, most people you know will do better in the future than now. And of that group, some will turn out to be extremely successful. If you believe that's the case, then you should help as much as you can. If you don't, it's time to get new friends [4].

Here's a couple of examples putting this into practice:

Acting as a mentor for others, and expecting nothing in return. You can do this via your college alumni system, at work, or even something like Vice Ventures' Young VC mentorship program (applications end today fyi!)

Supporting friends that are struggling, with whatever means you can afford. Pay full price for their stuff if they have a business, make introductions, and give advice where appropriate.

Being open-minded to new people and experiences. Realising that there's many paths to success and that others might become successful in ways you can't even imagine. You're handicapping yourself by only helping

At critical moments in time, you can raise the aspirations of other people significantly, especially when they are relatively young, simply by suggesting they do something better or more ambitious than what they might have in mind. It costs you relatively little to do this, but the benefit to them, and to the broader world, may be enormous.

|

I've presented the case for investing in others, and let's look at tradeoffs:

Mentoring people is usually a thankless task. The story of my life is getting asked for advice, giving it, and then having people completely ignore it. And this is ok! A fundamental rule of giving advice is you have to be prepared to get ignored

You might not be in a situation to help others, or the cost of helping is too high. Going back to the lottery example, if each ticket was the cost of the lottery prize, nobody would play it. In such cases, help to the extent you can.

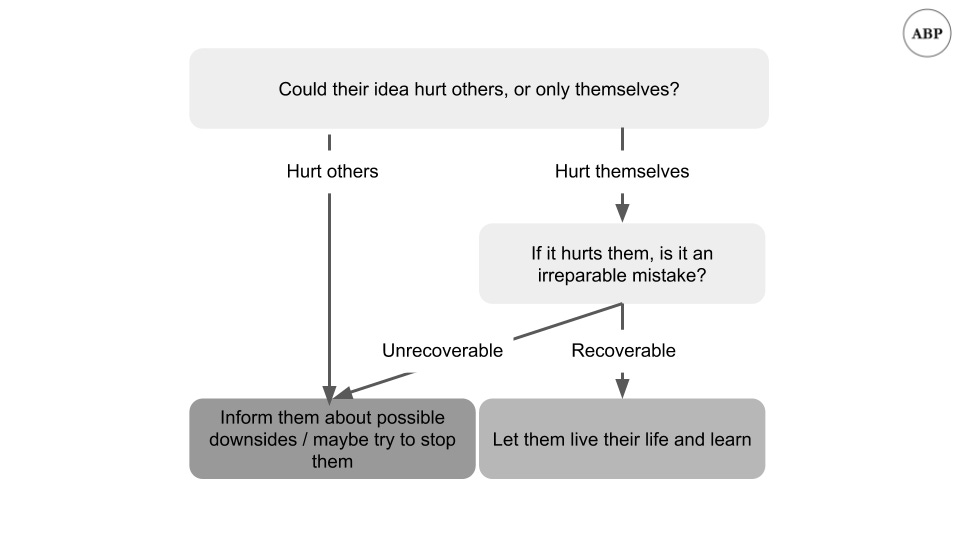

You're worried that encouraging others on fruitless causes makes them suffer even more when they fail. This is a personal decision, and my framework here is something along these lines: Does it hurt others? If it only hurts themselves, would it be a permanent, irreparable mistake? If not, just let people experiment and figure things out from experience [5].

|

One last point. Some might take the above message to the extreme by aiming to meet everyone, signing up for Lunch Club, Cuppa, and whatever the latest anonymous networking app that's always 90% male is. We probably also know someone who claims to know everyone, but somehow is never able to offer to help.

I don't think that's an effective approach either, due to the superficiality of connections when you aim for quantity [6]. Aim to be genuinely interested in the person, what they do, and what they're passionate about. It's hard to tell on first impressions, but people catch on after a while.

With that in mind, I also want to put money where my mouth is. I'm introducing something new for the newsletter: Guest features

I'll irregularly feature guest posts. Think of these as a "best of" or "most representative" article for the person. Sometimes there'll be Q&A.

The intent is to highlight people that should be even more widely known; "underrated" if you'd like. This roughly means they shouldn't already be making a living from their content, but I'll treat it on a case by case basis. Feel free to reach out with suggestions! [7]

I've a preference for writers since it's easier to showcase their work, though I'm open to exploring other formats.

The first guest I'm having is Brett Bivens of Venture Desktop, and you'll see more of his work in the section below.

Let's return to our lottery example. We've looked at it from the lottery ticket buyer point of view, let's look at the people running the lottery. Lotteries are great businesses that print money; people are essentially paying you money for the privilege of giving you even more money. You're not guaranteed to win the lottery, but you're guaranteed to lose if you bet against them.

Not investing in others is equivalent to shorting the lottery [8]. It implies you're betting against the success of everyone else, and that's an easy way to be very wrong.

Don't short the lottery.

2. Why do poor people play the lottery?

The section above got me to think about lotteries. There's a particular quirk about lotteries that can be unintuitive, and I want to explore that briefly - Why do poor people play the lottery?

The typical argument goes something like this:

Poor people don't have a lot of money

The more they pay down debt, save, or invest, the better for them

Lotteries have negative expected value, i.e. you expect to get <$1 for every $1 you put in

Poor people are aware of the odds and know they'll lose money on average

Since the lottery makes them worse off, they're dumb for doing so, cue laughter at poor people and some superiority complex from armchair economists.

Points 1 and 3 are true by definition. Point 4 is usually true; we'll take it as a given.

So the parts where this argument breaks down are potentially points 2 and 5.

The problem is defining "better," and it's not just a nitpicky semantics argument. Sure, they're worse off "economically," i.e. have less money. But we need to ask ourselves, what did they buy for their money?

A dream. They bought a dream.

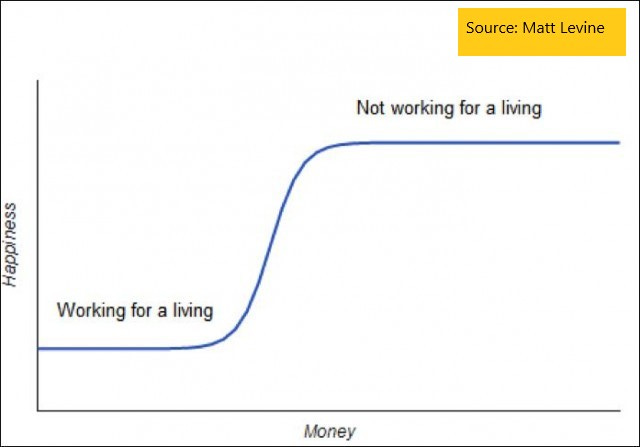

For $1 they bought a wisp of a dream in which they won and never had to worry about money again. As Matt Levine writes:

To be pretentious, although not especially accurate: utility is discontinuous at not having to work for a living.

|

Winning the lottery is such a life-changing event for most, that even the dream of winning a lottery is valuable. When you're that far down, you can only hope for a long shot to reverse your fortunes. And sometimes you might even care less about winning, and more about the anticipation of winning.

Viewed purely on a monetary basis, playing the lottery makes no sense. Viewed from any basis which accounts for human behaviour, no wonder everyone wants to play the lottery.

If you think this is irrational, think of any long shot decisions you've made in life. Immigrating to a new country, betting on your favourite team, having children. We do many things that are net negative monetarily, but give us something else in return. We dare to dream.

In some ways, we're all playing the lottery of life.

3. Brett Bivens feature: The Storytelling Thesis

As mentioned, below is the guest post from Brett Bivens. Brett writes at Venture Desktop, which explores the ideas, companies, and people that shape the innovation economy.

|

Brett's piece today is about the importance of storytelling, making it a good companion piece to my earlier article on stories

Here's his intro:

I wrote this a few years ago as I was making the transition from working in startups to investing in them and as I was reflecting on the "best" founders I had interacted with.

Everything I've learned since has strengthened my belief in the importance of storytelling in company building.

Hiring, selling, fundraising...storytelling is central.

For companies — large and small — each day is spent telling your story over and over again to all of your key stakeholders. Hiring, selling, raising capital…the storytelling doesn’t stop, it simply changes contexts.

Where collections of people have existed, so too have stories.

A company is a collection of people. A startup company, to use one definition, is the largest collection of people you can convince of a plan to build a different future.

The way that this collection of people — employees, investors, even customers — becomes convinced of that future is through storytelling.

Yuval Noah Harari has famously pointed out that “humans control the world because we are the only animal that can cooperate flexibly in large numbers.” Storytelling is the skill enables this large-scale cooperation.

In the same way, effective storytelling enables companies to separate themselves from competitors and gain control in the marketplace.

Good storytelling...

...bridges gaps by building context and conveying empathy which reinforces commonalities, minimizes cosmetic differences, and helps both sides find common ground. We see ourselves and project our own experiences onto the narratives others build.

...makes it possible for large collectives to share systems of beliefs and visions of the future. This applies to companies like it does to religions and political or social movements.

...connects the dots. It shifts the view from “what happened” to “why it happened”, “what will happen” to “why will it happen”.

Progress depends on storytelling and on the evolution of who is empowered to be a storyteller. When an overmatched collection of individuals come together to build compelling stories, they not only make their internal bonds stronger, they also create advocates on the outside. From there, the cycle repeats itself. Social movements start small. Religions start small. Businesses start small.

Stories are both the oxygen and the sustenance of these nascent groups. Stories keep these groups alive. Stories help these groups grow. So long as the right story exists, so too does the movement.

Questions for Brett

1. What are you practicing deliberately? E.g in the same way a football player would train drills to consciously improve

There are three things I am practicing deliberately.

The first is writing and I expect this will be a continuous practice for the rest of my life. Good writing comes from clear thinking, so the practice of putting thoughts on paper (and sharing publicly) is an incredible exercise in helping me develop my own perspective on areas that are important to me. In addition, most of the important career opportunities I have had and many of the professional relationships I have built have occurred as a result of sharing ideas in public. These opportunities and connections have ramped up significantly over the last 6 months as more have [sic] my writing has found an audience.

The next two are closely coupled - I am studying French and also trying to better understand the cultural, political, and economic history of Europe. I moved to France about two years ago to lead the European efforts for TechNexus, the venture firm I work for. It was also a family move as my wife is French. Language and cultural context are so critical to fully integrating into a new community so I'm highly motivated to continue progressing in these areas.

2. What are the top frameworks you use to understand the world?

This has been another "practice" area for me over the last few years as I've done a much better job of documenting different principles and frameworks that I encounter and their applications in various parts of my life.

One key framework that I've been very interested in lately is the notion of "Accumulated Accidents". This idea was first identified by Clay Shirky and introduced to me in Dave Bujnowski's analysis. It asks whether certain societal or economic structures represent an “ideal expression of society” or whether they are simply a series of accidents that can be unwound in the right circumstances. Identifying areas where accumulated accidents are coming together with new technologies or social norms often creates tremendous investment and company building opportunities (areas like health, housing, and education stand out here).

A non-comprehensive list of others frameworks that I think about often are the value of compounding actions (I've experienced this with my writing over the last 6 months), the proximity of one's strengths and weaknesses, George Soros' idea of Reflexivity, and the role of uncertainty vs. risk in decision-making.

3. What do you wish more people ask you about?

Living and working in India.

I moved to Bangalore when I was 23 to spearhead international expansion for a startup where I was on the early team. In a short period, we grew the India team that I was leading to nearly 200 people. As you might expect from someone with absolutely no experience in an entirely new culture, I made a ridiculous number of mistakes on what seemed like a daily basis. I learned a ton about prioritization, managing my personal psychology, and cracking cultural codes in order to better understand the motivations and perspectives of the people I was working with.

I also met my wife a couple months after moving to India, so the period was pretty momentus on a personal level as well!

If you liked this, you can find out more about Brett on his substack here and twitter here

Other

Financial engineering playbook from Gabelli Funds, h/t Dave Ambrose

If you’ve read this far you’d probably want to influence the future of the newsletter. Fill out the 7 question reader survey here to do so

Footnotes

I just used the first result when I googled "most famous celebrity," so pick whoever you want here.

I say this not knowing the current state of relationships Beyonce has with any of these people, and it's more to just illustrate the point, as you'll see shortly

Life goals. The lightsaber battles and spooky story inconsistent ghost abilities, not the getting chopped in half bit

I'm only half joking on this point. If you find yourself surrounded by people that make you think "i'm going to stagnate and be stuck in an unhealthy environment," you should get out while you can.

Example 1: If your friend has an unconventional business idea, the default should be to support them. Example 2: If your friend's unconventional business idea is to commit insider trading, you should probably warn them against it. Example 3: If your friend's idea is to commit insider trading by beating up someone else in a dark alley to get next quarter revenue numbers, you should probably run away. Err on the side of kindness and helping others.

Nothing against Lunchclub and the like, I'm an occasional user of the service.

I can't guarantee that I'll feature them, and will take a look at all suggestions

Technically some could say you're neutral and not long or short. But if you think of everyone in the world as forming the market index, and the subset of people you're able to meet as a portfolio, not investing in the subset is like having a negative weight.