Y Combinator is probably the most impactful institution for the creation of new startups, period. With their core accelerator program funding the likes of Airbnb, Dropbox, and Stripe, as well as their Startup School program reaching far and wide to millions of founders all over the globe, it’s clear that YC has set itself up to be the de-facto place to go if anyone wants to start a startup.

One of the reasons Y Combinator is able to so consistently put out so many great companies is because they consistently reinvest their revenue back into the YC ecosystem. With their returned capital from exits, they hire new partners, developers, and vendors to make Y Combinator much more valuable to the startups it serves. The way YC makes money is a little different than most. They don’t charge startups to join their program or charge a fee for investors to invest. Their primary business model is by taking 7% of every startup that goes through their program, help them get as valuable as possible, help them raise capital, and then profit when the startup exits for (hopefully) billions a decade later. If this sounds like a VC firm to you, you’re right. YC is a VC firm, but works in a much more standardized way.

Y Combinator - The Basics

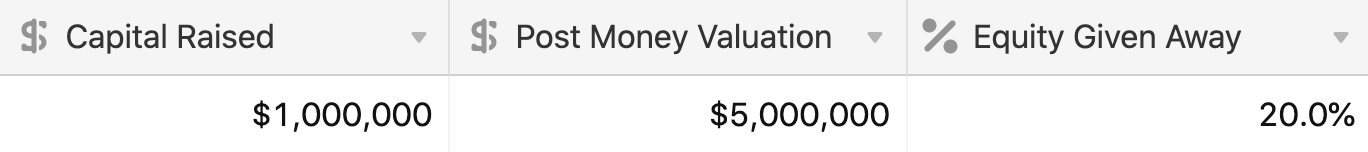

As mentioned, YC takes 7% of any startup wanting to join, and in exchange, the firm invests $125,000. N f2ote, this number changes every few years depending on market conditions. We can do some quick math here. If YC is investing $125,000 to own 7% of a startup, YC is valuing that company around $1.8M post-money.

Once a team enters the program, YC’s goal is to help make their companies as valuable as possible, so investors want to invest at a high valuation after demo day. This usually looks like having founders set aggressive goals, giving them a system for accountability, allowing YC companies to sell to the YC network, etc. At the end of the program, YC hosts a demo day where they invite thousands of investors to check out the newest batch of startups.

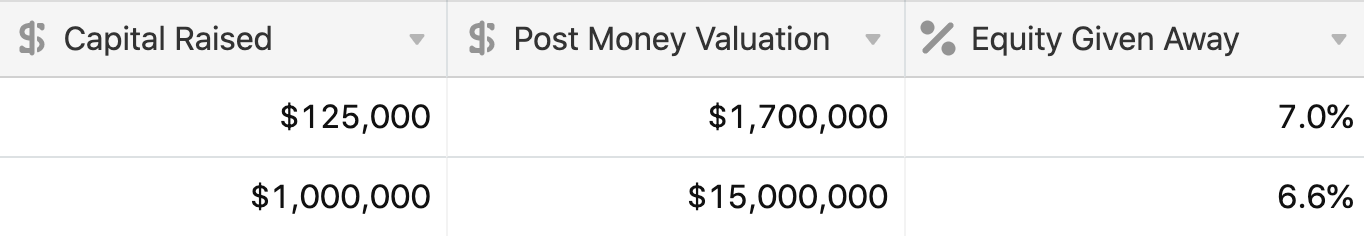

Because of demo day, an average YC company raises at well over a $10M valuation, on average. With that said, some can raise at a much higher valuation than that, depending on investor appetite. Many raise at a $20 or $30M post-money, and some even more. Once a startup raises capital, the YC core program has done its job. Then it’s a quick break and then time to read applications for the next batch. Rinse and repeat.

The YC Boost

Now for most founders out there, YC seems like a dream situation for them. They get an investment from one of the best VC firms in the world, go through this amazing program, and raise at a great valuation at the end of it all. For many, this is a deal of a lifetime, and it makes sense that 400 or so companies will take this deal in 2021. With that said, there are still many tier-one founders that reject YC if they get an offer. Many question if the YC deal is still worth the 7% + pro-rata rights that come with the resources.

It’s true; 7% is a chunk, and in a world where fundraising is so easy for many founders, YC has always needed to defend its value to founders to maintain its market edge. Their justification for taking 7% has been “because our brand and resources are so good, this will pay back itself at demo day when the startups raise at 2x of 3x valuation than they would have otherwise”. Call this the “YC Boost”. This is fairly logical, and it checks out too. Let’s do the math.

Without YC:

With YC

So in this scenario, a startup could raise a little more money with YC and give up 33% less equity than if they didn’t have YCs help. So from a cap table perspective, YC allows them to dilute less of their company when raising a seed round.

Because YC invests at a $1.8M post-money valuation, with a pro-rata rights, founders need to raise at a certain valuation after demo day to avoid excessive dilution on their cap table. If the startups didn’t raise at a high valuation afterward, the YC deal + their seed fundraise would put them in a difficult equity position for future financings. Let’s look at two scenarios where a startup isn’t able to get the YC boost in fundraising, even after going through the program.

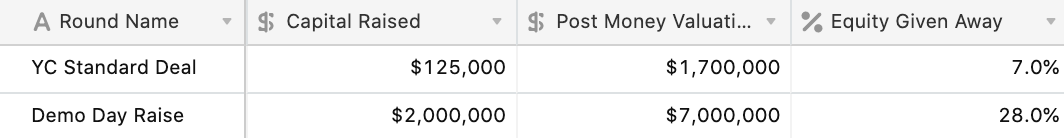

A $1M Round After YC, With Weak Terms

A $2M Round after YC, With Weak Terms

In these two situations, the startup would have sold for 21% for $1.12M or 35% for 2.12M. These types of numbers could scare investors that are downstream for the Series A or B. This is why they heavily encourage their startups to raise at the highest valuation they can. Because if they don’t, their cap table is fucked.

In summary, the only way for YC to be worth it for a startup is by raising at a large enough valuation to cover the cost of the lowball deal YC invested on. YC is well aware of this. Some founders are, and some aren’t. Yet what most founders don’t ponder is what the implications are of taking YCs SAFE deal, which is pretty much forcing them to choose the VC route from day one.

Venture Capital is a One Trick Pony

Many of these people applying to YC probably are capable of building any sort of company, whether it be a mom and pop shop all the way to Uber scale company. The problem is that no one knows what they are actually capable of until they try and enter a market with a product/distribution plan, and put all their effort and force into it. Different combinations of markets, products, and founders all need a different type of financing. Some could use a business loan. Others a revenue-based financing agreement. And some need venture capital. And it’s hard to know what the right type of capital is when starting a company

Yet when YC makes an offer, they force a company to decide right then and there what type of company it is, and how it will be financed. Most founders think they understand this, as they want to build a billion-dollar company, but they don’t know the implications. As many of my readers know, venture capital is a hits business. It’s a one-trick pony, or simply fuel to pour onto a fire.

In VC, the 1-2 winners cover the 20-30 losses in a portfolio. And to a VCs economics, as long as they invest in the 1-2 winners, the 20-30 losers don’t matter to them or to their LPs. It’s a rough industry. And although a $50M exit for a founder may be meaningful, it will not be meaningful to a VC. And this creates conflict in the incentives between founders and VCs. This is likely one of the reasons why 99% of companies actually aren’t venture-backed. Very few businesses were built for venture capital, but the market has forgotten this (on both sides).

The Dark Side Of The Deal

What YC is doing is it’s going and selling nobodies like you and me on this promise of building a world defining company. And we see the logos. We see the names. And we’re like, ‘hell yeah. I want to be like them”. And for the lucky/hard-working ones, YC picks them to build these “billion-dollar companies”, out of tens of thousands of applicants.YC is giving these founders hope and confidence by picking them, seemingly feeling them like a needle out of a haystack. YC is giving them a chance at changing the world; To solve a problem near and dear to their heart. Who in their right mind would say no to this? This is what makes the YC deal so damn appealing.

The issue is that nobody is going to tell them what they are signing up for when they sign that SAFE and take YCs money. Because what happens if someone goes through YC, then raises at a $20M post-money valuation from Sequoia (to make up for the low YC terms)? It means they need to exit for $200M minimum to be meaningful. Chances are they’ll need more capital to accomplish that, so they raise more money, at a valuation that allows them to not dilute even more, like $80M. Now the companies need to have a billion-dollar exit to matter to VCs.

So these little decisions that a founder made at the ideation stage of Y Combinator actually have a massive impact on the future. The truth is, if someone goes through YC, they can’t build anything but a venture scale company. Optionality goes completely out the window. And yes, there are the bootstrapped edge cases like Zapier or Wufoo, but these are very rare and don’t succeed nearly as often. What usually happens is that 70%-80% of the founders that YC funds figure this truth out too late, realize they can’t raise a Series A or B or become a “billion-dollar company”, and fail. But who failed here? Did the founders fail? No, I don’t think so. I think the system failed the founders.

How Truly Expensive is Y Combinator?

I am not here saying that Y Combinator is a bad organization. They do a lot of good for the world and create tons of value for the founders that strike it big. But what I am saying is that by taking investment at these terms, unless the startups plan on bootstrapping the rest of the way or failing, they are completely obliterating any chance these founders have at building the type of company they may want to build in the future. They are submitting themselves to build the type of company that the Bay Area needs them to build so everyone can keep their jobs.

Y Combinator needs ambitious founders like us to shoot for the moon. They need big thinkers, problem solvers, and missionaries. VCs need people to solve big problems by building and scaling billion-dollar companies. The system needs founders to keep it running smoothly as is. The questions I leave you are the following:

Do you need venture capital, today, to work on what you want to work on? Would you be satisfied by making $1M or $20M in an exit, not $750MM in an exit? Do you actually want to build a billion-dollar company, and absorb the headaches that come with that? Think about it. Because once you do, you’ll find that you only wanted to build a billion-dollar company because someone else told you you needed to, or else you didn’t matter. No, if you don’t build a billion-dollar company, the system is the one that doesn’t matter.

So how expensive is Y Combinator? I’d argue the SAFE investment terms are the cheap part of the deal. The expensive part is committing 2-10 years of your life to something, knowing (or not) that you have a 10% chance of getting really rich+ making an impact, and a 90% chance of leaving with nothing. The expensive part is the opportunity cost of what you could have built if you weren’t so focused on getting to $100M ARR in seven years. The expensive part is you being a recent grad being told that this way is the best way by your, according to “the startup gods”, without realizing that you’re opting into a decade long game of Russian Roulette. Of course, YC is not here saying “billion dollars or bust”. With that said, if you sign that SAFE agreement and take their money, you may as well.