I am back in the Pace office and feeling grateful to be back. Have been meditating and gaining clarity on noise and signal, reality and perception.

What we share is Fakepixels, a space for honest inquiry, creative courage. Here, we are not afraid to ask bold questions and unveil invisible forces reshaping the status quo.

If you’re new here, welcome.

I met with a founder who’s building a point solution for identity authentication on the web. There’s nothing fancy about the product. It simply works. Understanding how much complexity underlies simplicity, I reached out to have a conversation. The absence of grandiose narratives only accentuates the clarity of the product’s vision. Our conversation ended up flowing to a place where neither of us was talking about authentication or venture, but rather about the philosophy of product creation.

We wanted to not disturb the garden. You can think of us as pruners of the weeds, so the paths clarify for people to fully enjoy the beauty of what the garden already offers.

The metaphor to nature is not only refreshing, but an important one. His approach comes in contrast with another school of thought that focuses on destroying existing gardens to create new ones. The existing garden no longer caters to what we want anymore, and the new promise land will provide more than we have ever dreamed of. Then miracles are built, like the pyramids, Machu Picchu, the Great Wall. It was almost through the conquest of nature that we’ve derived our meaning and potential. Such spirit is embodied by the old man’s thoughts in Hemingway’s famous work:

The fish is my friend too...I have never seen or heard of such a fish. But I must kill him. I am glad we do not have to try to kill the stars. Imagine if each day a man must try to kill the moon, he thought. The moon runs away. But imagine if a man each day should have to try to kill the sun? We were born lucky; he thought.

Recent research discusses the relationship between the rise and fall of ancient civilizations shows some clear correlation between deforestation and the civilization’s collapse. Japanese scholar Yoshinori Yasuda conducted extensive research on the topic of civilization and the environment. He wrote about the Mayans, who created a sophisticated society and accomplished a great deal while it lasted.

They built great cities and monuments, even public works. Because their tropical rainfall varied widely from year to year, the Maya created reservoirs. The one at Tikal in Guatemala holds enough water to sustain 10,000 people for a year and a half. Even so, the Mayan population grew to a peak population for five centuries and ultimately collapsed. This happened because the Mayan society struggled to feed its people. As the Mayans downed trees for firewood and lumber, once-verdant hillsides became infertile. A major drought in 800 spelled the end of Mayan society. The drought and earlier deforestation made food scarcer and prompted war over scant resources. In a downward spiral, constant warfare cut into agricultural production. It’s likely that Mayan society didn’t collapse all at once but in increments.

The collapse of ancient societies debunks a common myth that compared to modern societies, indigenous people are innately more ecologically sensitive, more in harmony with the natural world, and less likely to pillage their sustaining natural resources. The truth is more complicated. Almost every society, no matter what race or geography, struggles to nurture resources that seem infinite — until they’re gone. The thought of deforestation or climate collapse never alarms anybody, as if it’s a myth told by some foreign deity. What’s sobering is that it’s not simply the loss of trees that have destroyed civilizations, but the loss of thought and wisdom gained from our relationship with nature.

One ancient Japanese proverb reveals the foolishness of cutting a horse chestnut tree and planting a new one in hopes of getting fruits faster, as it generally takes three generations for the tree to bear fruits of high quality. Another proverb says “leaves the first and largest mushroom as a seed for future generations when you pick mushrooms.” The same lessons were learned on the continent of Africa, where a proverb describing intergenerational goes: “we did not inherit the earth from our parents; we are merely borrowing it from our children.” Today, we’d go into a forest and pick up the largest, most edible mushroom we can find.

As an unnatural product of both Western and Eastern philosophies, I find myself always struggling with the tension between these two concepts of human logic: that all things in the universe in a continuous cycle, or that there are an Alpha and an Omega from the top to the bottom. The former is the worldview of Buddhism and the latter is that of Christianity. The former focuses on “nature and mankind as one”, and the latter inspires the divinity in humans to create unimaginable feats. Technology, by nature, needs to be disruptive and stands almost at the opposite end of Buddhist thoughts. Where features of science of technology are materialistic, seamless, efficient, and powerful, Buddhism derives enlightenment from processes that are spiritual, difficult, patient, and abstinent. It’s always the case that we need to make a choice, but what if the choice is an illusion, the only way forward is to embark on a new path?

Religion is produced by the natural features of the land, and the technology we build is only a mirror of what we desire as people. When we look into the mirror now, what do we see? What would technology look like if we discard the duality of the Christian’s “good and evil” and leverages the sublimity of human potential to achieve the kind of harmony that is so unnatural to our never-ending desires? Time is ticking, and the speed of innovation needs to accelerate to prevent another collapse, while relentless experimentation that only focuses on short-term outcomes no longer suffices.

The conversation with that founder seems to take me onto a path where conflicting schools of thought seem to come to a balance. And that is hope.

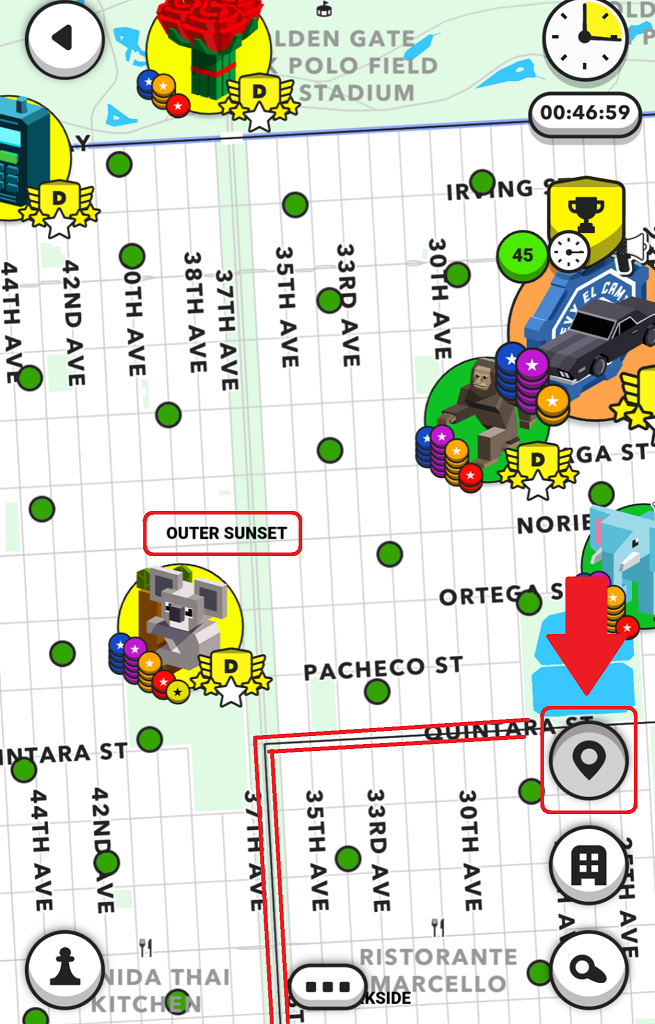

Monopoly, but with it’s getting real.

|

I grew up owning a set of Monopoly, and I was quite competitive with it. I remembered when I visited Penn Station in New York for the first time, immediately I was reminded of the golden rule I still know by heart.

Owning all four railroad stations is powerful.

Buy every property you land on, even if you need to take out a mortgage.

Yellows and Reds properties are good, but Oranges are the best.

Neither of those rules translates well into reality. Perhaps only in my dreams, until Upland released its digital real estate game that lets users purchase virtual properties that are an overlay of the real world for real money. Similar to rules in Monopoly, in order to collect more rent on the properties you buy in-game, you have to acquire three properties that are related in some way. You cash out by selling virtual goods/properties via the marketplace to other players who purchase using fiat, or U.S. dollars. Instead of putting the property up for sale for the in-game currency UPX, the user can decide to put it on the marketplace to be bought with fiat.

By using fiat currency, Upland can stay in compliance with regulations in the U.S. Even If the game ever shuts down, the players will theoretically be able to take their property and move it elsewhere, in contrast to other games where players don’t really own the objects that they build or trade.

Upland also entails a natural scarcity of available properties, as they are all based on real-world addresses. Players can buy a virtual property based on the real world because it’s something people can relate to, either because they want to own what they possess or aspire to in real life. The first city they’re experimenting with is San Francisco. Not a surprise.

What could go wrong? Well, how would you feel if someone owns your property in the digital world, and you have no idea until you discover that your home has become a celebrity in an alternative universe. This can get philosophical quickly because you can argue that what they’re buying in Upland is a representation of your home, not your actual home. Some rights are infringed here.

The mission of the team, however, is a respectable one — to bring the benefits of blockchain technology to the mass market, and they are educating the concept of digital ownership through a casual gamified experience. After all, we learn best through analogies with something that we’re already familiar with.

Toys for adults?

We’re not talking about adult toys here but toys for adults. There’s a big difference. Our beloved childhood memory Play-Doh is launching a grownup line for adults, encouraging adults to “squish and sniff it like no one is watching."

|

For adults, toys usually come in the form of collectibles. When you have more money but no time, owning a part of something rather than actively participating seems to fulfill fragments of a distant dream. The desire led to the popularity of Funko Pop! figures — cute, compact versions of seemingly every major character and celebrity out there. From Alien’s xenomorphs to Game of Throne’s Three Houses, there are more than 8,000 different Pop!s. The publicly traded Funko raked in $795M in net sales in 2019.

Launched earlier last year, the company Youtooz has quickly established itself as the Funko Pop! for YouTube stars, working with content creators to produce their very own limited edition vinyl figures.

On StockX, these $30 figures are being resold for as much as $750. The resale market keeps the hype and discussion going about the figure and creator that it captures even after the figure sells out. The StockX for collectible soon emerges as a standalone company.

WhatNot launched this year trying to fill the gap. The GOAT for collectible introduces marketplace-specific features to help you discover new products through sorted groups and engage with the enthusiast community through live streaming. By becoming a verticalized marketplace, WhatNot can optimize the e-commerce experience by handling curation, fulfillment, and customer support, so the sellers don’t have to deal with any of that.

Maybe we’re staying at home for too long. Maybe we’re reuniting with our family and our parents. Maybe we’re stuck in our childhood room. Fragments of what we love about ourselves when we were a child start to emerge, and as adults who are now children of the capital markets, we find ways to weave our passion with our past dreams.

While kids are being watched, learning.

While adults are playing with toys, kids are working hard.

This week, ByteDance unveiled its first consumer hardware product: a smart light lamp with a display, camera, and built-in digital assistant to help kids finish their homework. The camera on the lamp will enable parents to tutor (or monitor) their kids and check-in remotely via a mobile app.

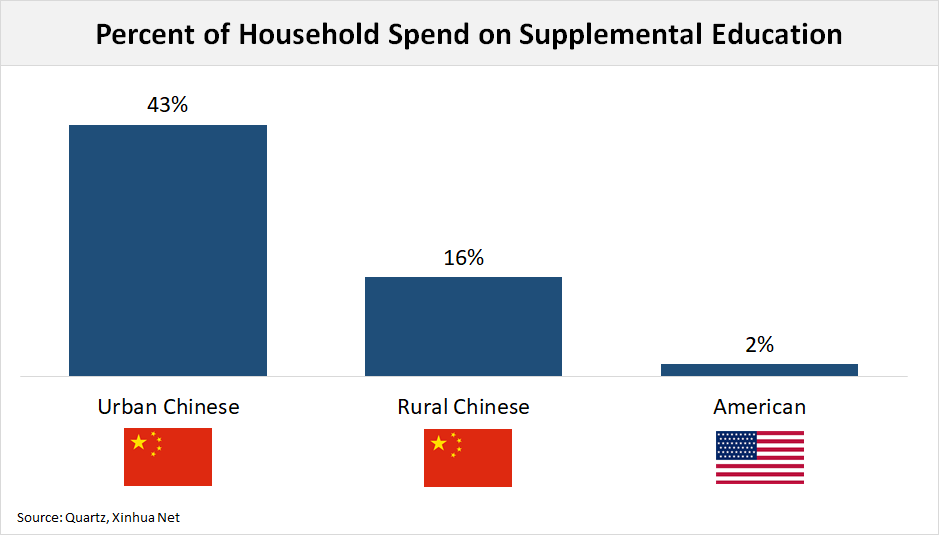

When we look at the Chinese tech market for comparables, the cultural and demographic differences are often overlooked in the analysis. China has a long-tail of technology users that don’t yet have access to the quality of education infrastructure as America, so a digital solution becomes not only a nice-to-have but a necessity. With increasing competition for the best educational resources that tend to concentrate in a few top universities in the cities, parents are willing to go as far as selling their property and live off one meal a day to support a child’s tuition. I grew up seeing posters that said “Children are the flowers of the nation. Children are the hope of the nation.”

Miracles are made. Tears are shed. Families are broken. Dreams are actualized. All because of education. All because, if the kids get into a good university, there’s a chance that the family can now live a life as they see on TV. Those are stories for another time.

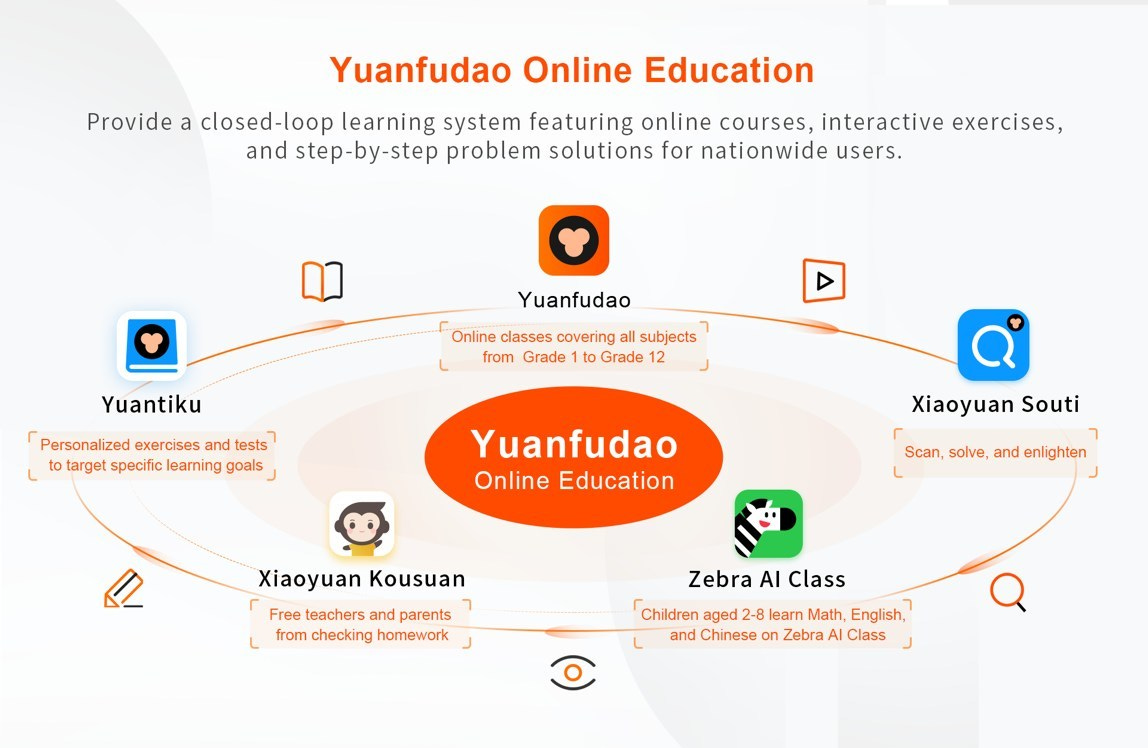

With that said, the Chinese startup Yuanfudao recently announced a $2.2B fundraising at a $15.5B valuation, making it the most valuable EdTech company ever.

From the graph above, we can see Yunfudao aims to be the super app for education. In the U.S. and other markets, we can find a unicorn targeting each of the areas above. The bundling of these fragmented solutions creates a self-enhancing ecosystem that provides all stakeholders with a holistic view of the progress and performance of the student’s learning. The platform boasts its AI features that automate a wide range of tasks, from curriculum creation to homework checking. Just like a full-stack software that helps a product team has better visibilities into user feedback through data, teachers and parents can now collaborate as PMs and data analysts, overseeing the performance of the most important products of the nation — the children.

A formula for innovation

Does innovation come from solving tangible problems or from dreaming crazy? The two schools of thoughts seem to always be at odds. Just look at the short and long investors of $TSLA yelling at each other on Twitter, or in general, Wall Street and SV.

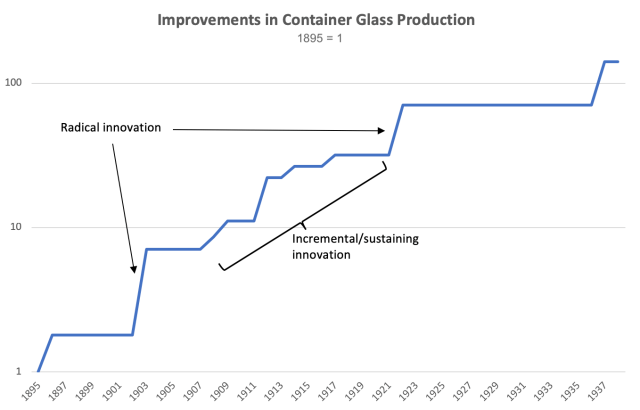

I came across Jerry Neuman’s latest piece on this topic and found the nuance underlying his thinking very enlightening. He shows a chronicle of innovation for container glass production in a graph below:

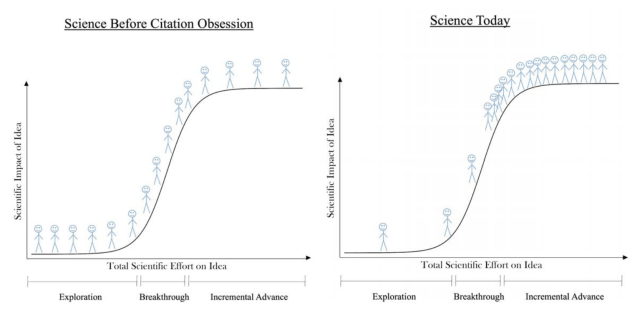

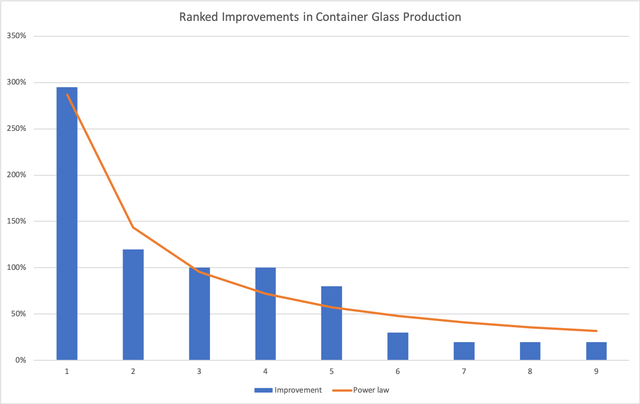

Neumann argues that innovation happens both in leaps and increments, and we attempt to create a histogram of these step-function improvements based on the impact it’s made (which can be subjective), you can see a curve that shapes somewhat like a “power-law” distribution.

Neumann argues :

If innovation outcomes are power-law distributed then there aren’t really two processes at all, it just seems that way. Kuhn, not to mention Clay Christensen, might have been seriously misreading the situation. It may seem like change faces resistance until it is big enough that the resistance can be swept away, but the truth may be that every change faces resistance and every change must sweep it aside, no matter if the change is tiny, medium-sized, or large. We just tend to see the high frequency of small changes and the large impact of the unusual big changes.

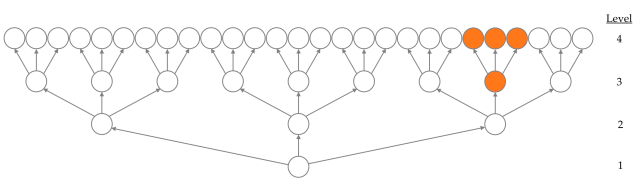

In other words, our perception of innovation overestimates the effect of low-impact incremental innovation and overlooks the impact of fundamental shifts, until our lives are shocked by its arrival. He draws a tree that illustrates how innovation starts as new nodes and grows into trees:

The likely over-simplistic mathematical model nevertheless reveals an important message:

The chance of an innovation at a given level depends on how many places there are to innovate at that level. If you look at the tree you see that there are only a few as you get near the root and many as you get closer to the leaves.

The technology products that we interact with daily are likely innovations of the leaves. It’s already common knowledge that the land of commercialization is not only more fecund but also more obvious. How many times have we seen “low-hanging fruit” in a pitch deck?

Neumann argues that existing infrastructure however is really pushing more innovators to the leaves that we can be talking more about dedicating time at the root level. We need to plant new seeds that can give birth to a new land. In his own words:

If you only reward innovators for results, the results you get will be anemic. If you support them for potential, your results might be spectacular.

You can read the whole piece here.

I’ve recently been mesmerized and healed by the art of Sungwen Chung.

She investigates the interactions between humans and systems, usually cocreating with machines. Created during the quarantine, her latest work Flora Rearing Agricultural Network (F.R.A.N.) is a project exploring plant and machine co-naturality.

The first iteration is a performance featuring the creation of a speculative blueprint for a new robotic network connected to nature. A backdrop of digital flora is linked to the artist's brainwave data, each flux in alpha-state seeding of new formations of sepals, petals, and leaves.

Horizontal Totalitarianism in Life and Literature No longer will anyone wish to be original, extravagant or creative, nor outspokenly contrarian, because this may cause that group of people who judge us with each passing moment to turn against us.

Horizontal totalitarianism exists independent of vertical totalitarianism of institutions, and it may be just as, if not more, dangerous, especially under the obscure shield of “being politically correct.”

Embers In The ForestThe fire had crossed the line. Adjacent to a torching tree, flames scampered in the branches of a green fir. Each flame stretched into a thin, tall strand, deposited flame on the branch above it, and rebounded to a fat, quivering teardrop.

The world is — literally and figuratively — on fire. Written by a frontline wildfire fighter, documenting his experience from helicopter drops to strategic lines of defense, as if from a war zone. It is a war zone.

The Complicated Legacy of Stewart Brand’s “Whole Earth Catalog”‘Whole Earth Catalog’ was very libertarian, but that’s because it was about people in their twenties, and everybody then was reading Robert Heinlein and asserting themselves and all that stuff,” Brand said. “We didn’t know what government did. The whole government apparatus is quite wonderful, and quite crucial. [It] makes me frantic, that it’s being taken away.”

The evolution of a cult leader that propagated the ideologies of early Silicon Valley hippies.

How Flash Games Shaped the video game IndustryFlash had a designer centric workflow that brought together art, animation, and coding. People that wouldn't have written code otherwise could gradually make their animations into games.

The essay itself is as fun as a game. It’s also a reminder of how joy was once so simple. The increasing sophistication of MMOs only enhances our nostalgia for simplicity. Look no further than our love for Among Us.

Fakepixels is a space for courageous thoughts.

We’re here to dream and agitate and question openly and unapologetically where we’re heading. We’re here to be vulnerable, honest, and true about who we are, and where we are. If you are interested in being a part of it, I would love to have you join the club.

If you enjoyed the ride, why not bring a friend?