So let's forget about the cat for a second. Although I've already decided he's a boy and I've named him Socks. He looks like he's wearing white socks on his front paws. And "Mittens" is too clichéd.

Let's look at Ahava's question: Why is this sentence so good?

And: How can we write like that?

Let's break down the simple beauty of this simple sentence:

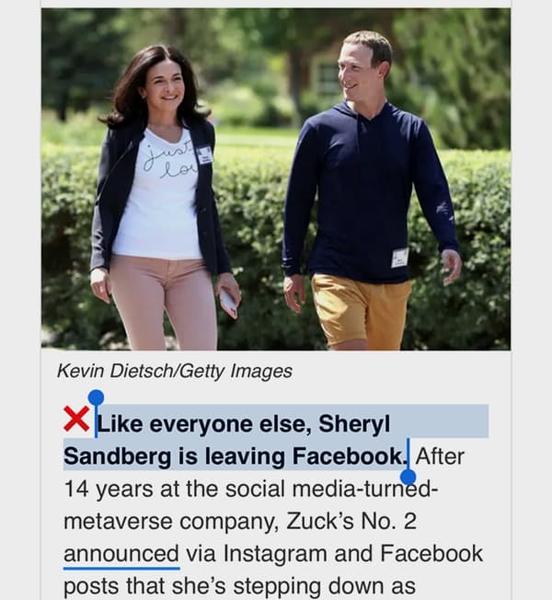

"Like everyone else, Sandberg is leaving Facebook."

➡️ Great writing starts with the audience. Morning Brew delivers news and insights to the "business leader of tomorrow"—code for "Millennials." The average age of Morning Brew subscribers is 30.

Facebook has famously been shedding Millennials just like my spaniel Augie has been famously shedding his winter coat. ("Fur" is truly a condiment in this house.)

That topic sentence works with Morning Brew's intended audience in a way it wouldn't for an audience of Boomers, who are still happily posting their Words With Friends scores on their Facebook profile pages.

* * *

Outside, it's started raining. I attempt to prop a travel umbrella over Sock's new window-well home. At the sight of it his eyes widen. He looks alarmed.

I abandon the umbrella idea and instead open the garage door so he can take refuge there if he wants. He doesn't. Instead Socks tucks himself tighter under the house's overhang, which keeps most of the rain off him.

I message a cat-friend named Eileen. (A friend who has cats, I mean—Eileen is not a cat.)

She tells me Socks is a tiger-striped tabby cat ("He's so beautiful!") and suggests I post him on a local community page on Facebook to see if anyone recognizes him.

* * *

"Like everyone else, Sandberg is leaving Facebook."

➡️ Great writing says to the reader: I see you. Morning Brew aligns itself with the audience with a kind of knowing nod: You've left Facebook, right? Or you rarely post, right? You use it only to monitor exes and people getting engaged from high school, right?

"Us, too!" Morning Brew says. "We are you." They mirror the collective reality of their audience in a spare 7 words—further cementing the Morning Brew brand as a news source with hip, sharp writing.

Would you see that topic sentence from, say, the Washington Post? Maybe. But probably not.

* * *

Oh, the irony. I haven't posted on Facebook since Trump was elected. And yet here I am—now thinking about Sheryl Sandberg and Morning Brew's sentence and Socks. When I open up Facebook I half expect my browser to question my typing—"www.facebook...? You sure? You feeling okay there, friend?"

I navigate to the community group and for the first time in 6 years I write a post. Let's get you home, Socks.

* * *

"Like everyone else, Sandberg is leaving Facebook."

➡️ Great writing doesn't need big words, big ideas, big anything. Maybe you think this sentence is a little... basic? It is. But it's also not.

The beauty of the sentence is its simplicity. It's not overwritten. It doesn't overexplain or play for another laugh. It's a universal truth expressed simply.

* * *

Facebook thinks maybe the cat belongs to a guy named Ian whose cat named Friday has been missing for two weeks. I call Ian and text him photos. "That's not Friday," Ian says.

Someone else thinks it might be a cat named Ace, missing since last September. Ace has no socks. I don't follow that lead. Someone else suggests that maybe Socks is not a boy and maybe She-Socks is pregnant?

Socks still hasn't moved. I'm starting to worry.

I cross-post to Instagram stories. I google "How to help a cat give birth." Then I add to the query: "...even if she's not my cat."

I start mentally placing the whelping box inside my house. Then I google "How to introduce your dog to new cat."

* * *

"Like everyone else, Sandberg is leaving Facebook."

➡️ Great writing has beats, pauses, full stops, sounds. Sentences are music. Words are sounds you hear in your head. Sentences thrum and vibrate to make the paragraph and the paragraphs make the page sing.

The beauty of the Morning Brew sentence is that it is perfectly balanced... you start the sentence not knowing exactly where it's going ("like everyone else"...? What are we leaving, exactly...?), then it comes in after the dramatic pause of the comma with the declarative punchline: Sandberg is leaving.

It would have been tempting to say something like "Sandberg is leaving Facebook. Like everyone else, she's realized it sucks."

The SEO consultant in the room would've said to do that—to front-load the sentence with the main idea—"Sandberg is leaving."

It's a simpler, more direct sentence, sure.

But it's also flatter. It lacks any surprise. It lacks humor, cheek, that insider nod to the audience.

A writer hears the music of sentences in their head. A writer chooses to put this phrase before that one to make the melody just so.

* * *

Eileen the Cat Person messages me: "How's it going?" Help, I say. "I'll be right there," Eileen says.

Eileen comes over, and then things start to happen quickly. Eileen thinks that Socks—who still hasn't moved more than a few inches in a few hours—is possibly traumatized, injured, pregnant, or a combination. She offers Socks food. Socks declines, but not rudely: He seems appreciative that we're trying.

Eileen calls the vet. The vet tells Eileen to call the town's Animal Control. Animal Control is off for the day, but a police officer comes anyway. The officer decides we should summon Animal Control after all. We wait: Eileen, me, Officer Kevin, and Socks.

Eileen is not only a cat person... she is also very, very good at small talk. She finds out Officer Kevin went to school with our kids. She shows him her daughter's photo. "She just got engaged!" Eileen tells him. Officer Kevin nods. "Well congratulations!" he says.

* * *

"Like everyone else, Sandberg is leaving Facebook."

➡️ AI robots don't hear music. AI robots might write. Some do it well. But they don't vibe with the music.

This point really is just a commentary on the last point. But it deserves its own bullet.

* * *

The Animal Control officer shows up. She has a cage and a big van, and Socks eyes her. Socks moves for the first time that day—inching closer to me and the entrance to the house, which was now open to encourage him inside.

And then as we are debriefing Animal Control, as Eileen and I and Officer Kevin all try to answer her questions all at once... we see movement across the street. It's a woman—no, it's our neighbor!—and she is running! RUNNING—like her shoes are on fire.

She's running and yelling something—and Officer Kevin instinctively turns to meet her. "It's never good when someone is running toward the police," he says. (I take a moment to consider that it's probably not good when they're running away, either.)

My neighbor is breathless... "I think... that's... my... cat," she manages.

* * *

"Like everyone else, Sandberg is leaving Facebook."

Part of me is loath to call writing "music" because it sounds precious. It sounds hard. I can't write actual music. Can you?

But you can learn to listen for the music. You can look for it. Appreciate it. Savor it. Capture it, as Ahava did.

Or capture it as I do—when I see a sentence I love, I copy it into my diary, just to feel what great writing feels like in my hands.

Noticing the music. Hearing it. Caring about it. Thinking about it more than most people.

That's really all there is to learning to become a better writer.

* * *

Socks is actually Lulu, by the way. She's an indoor cat who'd slipped out the evening before.

While she was on the lam, something had likely spooked her—a run-in with another animal? The headlights of a car? The sheer enormity of the world that freaks us all out sometimes? Some days I'd like to take refuge in a window well, too.

But she was fine. I mean... she is likely in need of psychotherapy—but she is otherwise healthy and fine. She melted into her mother's arms in that boneless way cats have. (Hmm. Maybe I *should* get a cat?)

Lulu's mom had been worried about her all day—unaware of the small drama unfolding across the street. Unaware of my assessment of her as probably an outdoor cat.

Unaware of how throughout the day Lulu had evolved in my mind from a chill, lounging squatter to an injured, possibly pregnant male named Socks. Unaware of Ian and Friday, the police, Eileen, Facebook, Instagram, or me.

* * *

Some people care about sentences. Some people care about cats.

I like to think it's all connected.

At one point I looked around my yard. The light was fading by then. Lulu's Mom held her. Lulu's Dad was there now, too, along with two police officers, Eileen, and me.

Six people plus Lulu, assembled there at dusk. All six of us, trying to find a way.