Hi there, it’s Mehdi Yacoubi, co-founder at Vital, and this is The Long Game Newsletter. To receive it in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

In this episode, we explore:

Let’s dive in!

Two interesting papers came up this week, one around sweeteners and one around alcohol consumption. I thought I’d share them as they cover practices/substances very widely consumed by most of us.

🍺 Associations between alcohol consumption and gray and white matter volumes in the UK Biobank

Abstract: Heavy alcohol consumption has been associated with brain atrophy, neuronal loss, and poorer white matter fiber integrity. However, there is conflicting evidence on whether light-to-moderate alcohol consumption shows similar negative associations with brain structure. To address this, we examine the associations between alcohol intake and brain structure using multimodal imaging data from 36,678 generally healthy middle-aged and older adults from the UK Biobank, controlling for numerous potential confounds. Consistent with prior literature, we find negative associations between alcohol intake and brain macrostructure and microstructure. Specifically, alcohol intake is negatively associated with global brain volume measures, regional gray matter volumes, and white matter microstructure. Here, we show that the negative associations between alcohol intake and brain macrostructure and microstructure are already apparent in individuals consuming an average of only one to two daily alcohol units, and become stronger as alcohol intake increases.

Pair with: What Alcohol Does to Your Body, Brain & Health

Key takeaways from the episode:

Chronic alcohol intake, even at low to moderate levels (1-2 drinks per day or 7-14 per week), can disrupt the brain

When people drink, the prefrontal cortex and top-down inhibition are diminished, and impulsive behavior increases – this is true in the short term while drinking and rewires circuitry outside of drinking events in chronic drinkers (even those who drink 1-2 nights per week, long term)

Damaging effects to the prefrontal cortex and rewiring of neural circuitry are reversible with 2-6 months of abstinence for most social/casual drinkers; chronic users will partially recover but likely feel long-lasting effects.

People who start drinking at a younger age (13-15) are more likely to develop dependence, regardless of the history of alcoholism in their family; people who delay drinking to their early 20s are less likely to develop an addiction, even if there’s a family history.

People who drink consistently (even in small amounts, i.e., 1 per night) experience increases in cortisol release from adrenal glands when not drinking, so they feel more stress and anxiety when not drinking.

With increased alcohol tolerance, you get less and less of the feel-good blip and more and more of the pain signaling (so behaviorally, you drink more to try to activate those dopamine and serotonin molecules again)

The risk of breast cancer increases among women who drink – for every 10 grams of alcohol consumed per day, there’s a 4-13% increase in the risk of cancer (alcohol increases tumor growth & suppresses molecules that inhibit tumor growth)

Regular consumption of alcohol increases estrogen levels in males and females through aromatization.

On this topic, I’ve been following the growth of non-alcoholic or low-alcoholic alternatives, as I believe it will be the future. Fitt Insider had a great issue about it.

In 2019, alcoholic beverage sales in the US surpassed $250B.

But there’s a catch: 43% of drinking-age Americans don’t consume alcohol. And 40% say they’re drinking less than they did five years ago.

Driving this trend, 66% of US millennials said they’re making efforts to reduce their alcohol consumption, citing motivating factors like well-being and weight loss. A sign of what’s to come, Gen Z is consuming less alcohol than previous generations.

Globally, the World Health Organization expects the proportion of drinkers to fall by 1.4 percentage points to 40.3% between 2020 to 2025.

I like to only drink for a few months per year (3—4), mainly around winter and summer, but everyone needs to find what works best for them. Some people can do moderation, and some would benefit from quitting entirely.

🍯 Personalized microbiome-driven effects of nonnutritive sweeteners on human glucose tolerance

Abstract: Non-nutritive sweeteners (NNS) are commonly integrated into human diet and presumed to be inert; however, animal studies suggest that they may impact the microbiome and downstream glycemic responses.

We causally assessed NNS impacts in humans and their microbiomes in a randomized-controlled trial encompassing 120 healthy adults, administered saccharin, sucralose, aspartame, and stevia sachets for 2 weeks in doses lower than the acceptable daily intake, compared with controls receiving sachet-contained vehicle glucose or no supplement.

As groups, each administered NNS distinctly altered stool and oral microbiome and plasma metabolome, whereas saccharin and sucralose significantly impaired glycemic responses. Importantly, gnotobiotic mice conventionalized with microbiomes from multiple top and bottom responders of each of the four NNS-supplemented groups featured glycemic responses largely reflecting those noted in respective human donors, which were preempted by distinct microbial signals, as exemplified by sucralose.

Collectively, human NNS consumption may induce person-specific, microbiome-dependent glycemic alterations, necessitating future assessment of clinical implications.

Pair with: I Was WRONG About Artificial Sweeteners? | Educational Video | Biolayne

I read this book after seeing Dr. Julie Gurner recommend it.

I can safely say it’s the most life-changing perspective I have had since I read Healing Back Pain.

I highly recommend it if you care about maintaining a long-term relationship. What struck me is how similar so many couples are. The author manages to explain his thesis very well and gives many examples (where you can easily recognize yourself or people you know!)

I won’t summarize the book as I strongly believe most of us would instead benefit from taking a few hours and reading/listening to it, but here’s the central idea:

Lastly, the reason this book is in the Wellness category is simple: divorcing a spouse is the second worst life experience you can have (after the death of a spouse) and often worsens the life of the many people involved durably.

Please do yourself a favor and pick it up. You can listen to it in less than a weekend!

Share

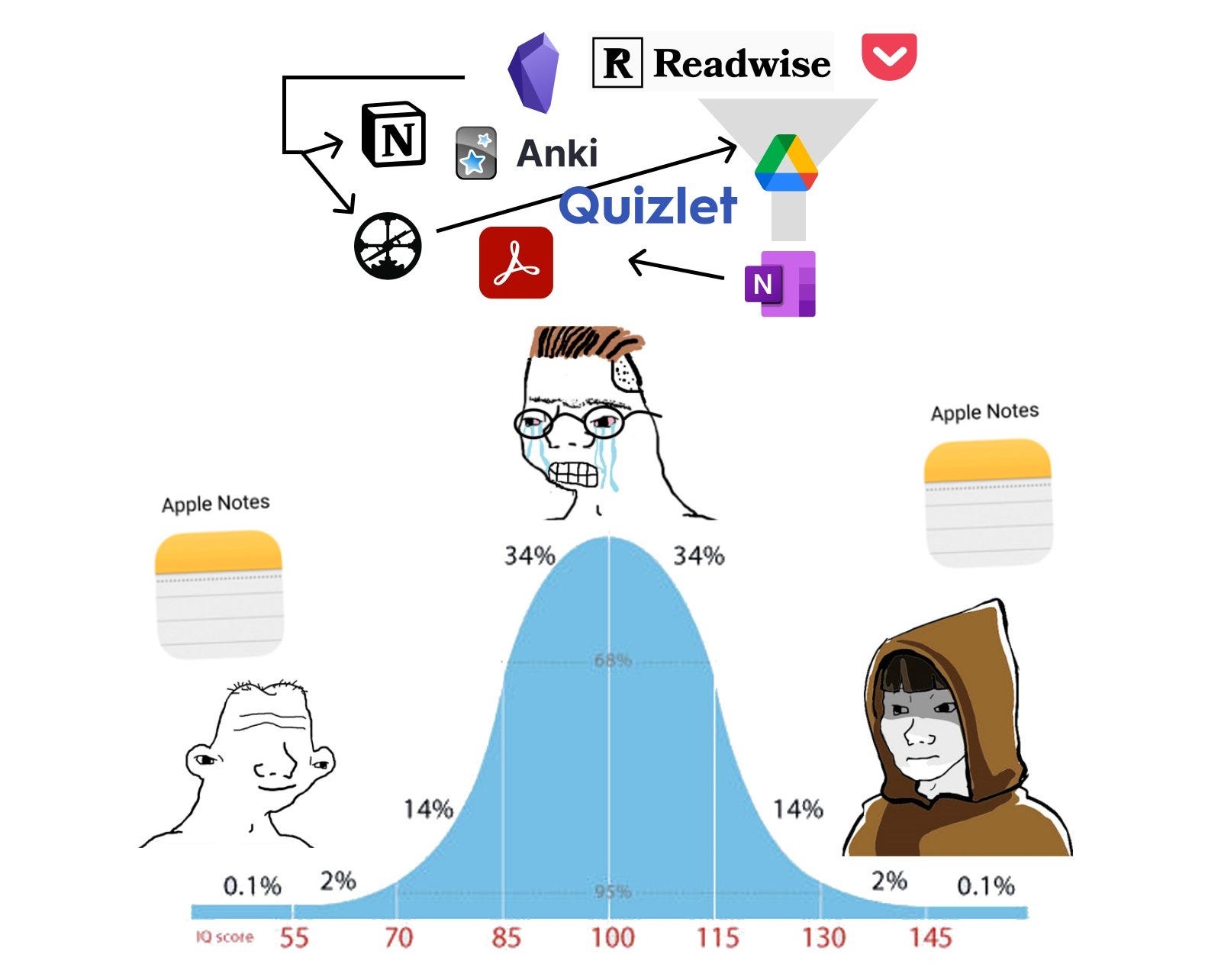

You might have seen the Midwit meme a lot on social media. My favorite implementation of it:

This great piece explains the phenomenon.

According to Know Your Meme, “midwit” is a derogatory term used to describe someone of average intelligence who mistakenly believes they are among the intellectual elite.

The Midwit Meme is usually used to defend a position that seems too simple and unsophisticated to be correct.

The idea behind the Midwit Meme is that sometimes the correct solution to a complicated problem turns out to be very simple. In this scenario, the genius and the simpleton will both end up with the right answer for very different reasons: the genius will fully understand and correctly solve the problem, while the simpleton will blunder into the right answer for the wrong reasons. (The simpleton always picks the simple answer whether it is right or wrong, an approach that will sometimes lead to the right answer by chance).

It is only the midwit who manages to get the answer wrong, by coming up with a complicated solution that appears smart and sophisticated but ultimately proves to be incorrect.

Why is this happening?

In Fooled by Randomness, Nassim Nicholas Taleb introduced the idea of Mediocristan and Extremistan. In Mediocristan, everything is normally distributed, and extreme events rarely happen. In Extremistan, there is an exponential distribution and extreme events happen much more often.

The Midwit Trap is to some extent just an application of Extremistan. The effectiveness of a simple solution depends on having a problem where one cause is responsible for most or all of the negative consequences. This is likely to be the case where there is a power law distribution or strict dependencies, but not so much elsewhere. We are used to solving problems in Mediocristan, where we usually cannot achieve a significant outcome with “one simple trick!” and so we are dismissive of simple solutions or simple explanations.

The Midwit Meme turns out to have a useful purpose, to remind us in a concise, memorable way that we cannot accept complicated solutions or explanations only because they feel smarter than a simple solution.

I found this piece on feedback interesting and worth sharing because it insists on something most other resources on giving & receiving feedback don’t cover: the need to first understand and sit with the feedback before thinking of how to improve.

Here are a few tips that have helped me respond to and grow with difficult feedback:

Focus on understanding the feedback before thinking about addressing it. When someone gives me feedback, it's tempting to immediately talk about how I’ll respond to it. Then I don't need to think too hard about the criticism because Look! I already have a plan to address it! And of course the person sharing feedback should be happy because I'm taking action on it right away.

But I find I internalize feedback more deeply if I focus only on listening. When I move straight to solutions, I don't take time to process what I’m hearing — which means I ignore useful information and discount the work of the person sharing it. I try to remember that the person is giving me feedback because they believe in me, and I owe it to them and myself to truly understand what they see.

Choose what to address. It took many years to realize that if I'm doing my job well and taking a bold stand, I'll always get feedback. Getting none isn't a sign that I'm perfect — it's just a sign that I'm not being bold enough.

So now when I hear an observation about how I’m presenting myself, I listen, think about it...and sometimes decide I won't take action on it. It's important that I understand the feedback, because that's useful new information, and helps me understand the cost of what I’m doing — but sometimes accepting criticism and continuing the way I am is still the right tradeoff.

Use the feedback to expand my map of the world. Not only is the person giving me feedback doing extra work to identify how I can get better and taking the risk of telling me something I might not want to hear, they’re also sharing something about how they see the world. If they’re telling me I’m “too impatient,” they’re not just commenting on my performance — they’re telling me how they believe a successful leader presents themselves, given their experiences. This gives me entirely new tools to think about success.

Look for other places I should be applying this same feedback. The best feedback not only applies systemically at work, it also crosses into my personal life. When I was told I don't ask for enough help at work, I wondered: where do I need to ask for more help at home? It turned out that getting just 10 more minutes a day of childcare made my commute (and therefore my whole day) 90% less stressful — but I had never before thought to ask for that.

There have been a lot of discussions recently around effective altruism after the publication of What We Owe the Future.

First, a definition:

Effective altruism is a philosophy and community focused on maximizing the good you can do through your career, projects, and donations.

I compiled a few interesting pieces here in case you’re interested:

Why I am not an effective altruist

So here’s my official specific and constructive suggestion for the effective altruism movement: People are always going to be off-put by the inevitable repugnancy, so to convince more people and grow the movement, keep diluting the poison. Conceptualize this however you need to. Internally, just say the normies don’t have the stomachs of steel you have. Your reasons why don’t matter. What matters is you dilute, in fact, dilute it all the way down, until everyone is basically just drinking water. You’re already on the right path. Do things like start calling it “longtermism” and make it just about caring about the future of humanity and reducing existential risk, which few people can argue with, and which can be justified in many ways. Under a big tent, let a thousand flowers bloom! Take rich people’s money and give it to your friends doing weird projects! Throw cash at AI safety even if we have no actual idea if it’s better than buying mosquito nets! Fork it over to Mars colonization!

We owe the future, but why?

For perhaps there is a simpler reason why I am not an effective altruist. In its current incarnation in America, EA is a philosophy both associated with, and in some ways metaphysically entwined with, the state of California and the West Coast of the United States. Which has always been utopian, in a way. It’s literally in the air, which, when I visited last month, didn’t feel like air at all. I couldn’t even tell I was outside, so innocuous was the temperature. In such beautiful country, and such perfect weather, and amid the blazing technological, financial, and cultural ascension of Silicon Valley, thinkers ensconced in that new world surely must feel a utopia is possible—and if utopia is possible, there must be some calculus to get us there, and utilitarianism is that calculus.

Effective Altruism As A Tower Of Assumptions

I have an essay that my friends won’t let me post because it’s too spicy. It would be called something like How To Respond To Common Criticisms Of Effective Altruism (In Your Head Only, Definitely Never Do This In Real Life), and it starts:

Q: I don’t approve of how effective altruists keep donating to weird sci-fi charities.

A: Are you donating 10% of your income to normal, down-to-earth charities?

Q: Long-termism is just an excuse to avoid helping people today!

A: Are you helping people today?

Q: I think charity is a distraction from the hard work of systemic change.

A: Are you working hard to produce systemic change?

Q: Here are some exotic philosophical scenarios where utilitarianism gives the wrong answer.

A: Are you donating 10% of your income to poor people who aren’t in those exotic philosophical scenarios?

The stories behind the stories that you read:

A friend who works in Washington told me something interesting about how he reads news reports. There’s the first order information - “XYZ agency is considering ABC rule”, etc. - that most readers absorb. But more sophisticated readers will pick out second order information, which is often much more interesting - “who are the sources for this reporting, and what are their motivations?”, “how did this article come to be written?”, “what may result from this article’s publication?”. My friend says that he reads the news primarily for this second order information.

For example, when this article came out about Bill Gates’ contacts with Jeffrey Epstein, most people reacted only to the face-value information. But savvy readers noticed that the sources for the articles must have been Gates Foundation employees who were now trying to harm Mr. Gates’ reputation. From this second-order information, it was possible to intuit the deep rift that had formed in the Gates Foundation.

Have you ever wondered why people want what they want? This paper explores an interesting theory.

The abstract:

We propose that a person’s desire to consume an object or possess an attribute increases in how much others want but cannot have it.

We term this motive superiority-seeking, and show that it generates preferences for exclusion that help explain a host of market anomalies and make novel predictions in a variety of domains.

In bilateral exchange, there is a reluctance to trade and people exhibit a ‘social endowment effect.’ People’s value of consuming a good increases in its scarcity, which generates a motive for firms and organizations to cater to such preferences by engaging in exclusionary policies.

Randomly barring potential consumers from the opportunity to acquire a product increases the seller’s profits both in standard monopoly and auction settings. Such nonprice-based exclusion leads to higher revenues than the classic optimal sales mechanisms.

A series of experiments provides direct support for these predictions. In basic exchange, a person’s willingness to pay for a good increases as more people are explicitly barred from the opportunity to acquire it. In auctions, randomly excluding people from the opportunity to bid substantially increases bids amongst those who retain this option.

Exclusion leads to bigger gains in expected revenue than increasing competition through inclusion. Our model of superiority-seeking generates ‘Veblen effects,’ rationalizes attitudes against redistribution, and provides a novel motive for social stratification and discrimination.

The idea that our desires are intimately linked to the desires of others around us isn’t new (see Wanting), here an additional component is added: we want what others can’t have:

The desire to consume objects or possess attributes that others want but cannot have seems to be a significant driver of demand in a variety of settings.

Voters appear to favor politicians who enact exclusionary policies which bar minorities and non-citizens from access to institutions and markets—in spite of the economic harm to themselves.

Firms and other entities appear to respond to a similar motive by practicing exclusionary policies that limit opportunities to purchase their goods or accessing their services.

Sellers advertise widely, but maintain product shortages despite persistent excess demand at the going price.

Well-known restaurants and entertainment venues do not increase the price or the capacity despite long lines, and luxury brands would rather burn millions in undamaged product than threaten their exclusivity.

Moreover, such ‘artificial’ exclusivity and limited access often appears to be a feature rather than a bug, intended to drive up demand by highlighting the privilege of consumption in light of how much others would enjoy the same product, but cannot.

While separate explanations have been proposed for some of these seemingly-disparate phenomena, we argue that they jointly point towards a model of preferences that generates a demand for exclusion.

I’m a big fan of Ivan and his philosophy around training. He reached a milestone of 1,000 days of squatting every day—definitely a positive voice in a world where fake nattys are taking too much space.

The sad reality of what you see on Instagram.

I just got a pair of these Gat Gripz to complement my training, work my forearms & arms better and prevent elbow pain. I’ll report on how helpful they are in a few weeks; let’s see if we can get to 20 inches!

Generally speaking, I think these body parts are underrated and undertrained (for men):

Don’t forget them in your training plan!

“It is a fault to wish to be understood before we have made ourselves clear to ourselves.”

— Simone Weil

Thanks for reading!

If you like The Long Game, please share it on social media or forward this email to someone who might enjoy it. You can also “like” this newsletter by clicking the ❤️ just below, which helps me get visibility on Substack.

Share

Until next week,

Mehdi Yacoubi