Not Boring by Packy McCormick - Working Harder and Smarter

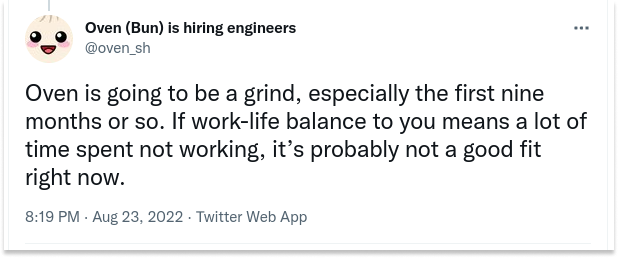

Welcome to the 9,080 newly Not Boring people 🤯 who have joined us since the last post I wrote in August — I need to take breaks more often! If you haven’t subscribed, join 152,217 smart, curious folks by subscribing here: Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Secureframe Secureframe is the leading, all-in-one platform for security, privacy and compliance. We wrote about the company back in 2021 in “This is How They Tell Me Secureframe Saves The World.” Secureframe makes it fast, easy, and cost effective to achieve and maintain compliance so you can focus on what matters: Scaling your business, serving customers and growing revenue. With 100+ integrations to core services, Secureframe helps hyper-growth startups continuously uphold the most rigorous global standards, including SOC 2, ISO 27001, HIPAA, PCI, GDPR, CCPA and many others. Secureframe also helps sales teams respond to RFPs and security questionnaires quickly and easily so they can close more deals, faster. Hyper-growth organizations like AngelList, Fabric, Doodle, Dooly, Lob, Slab and Stream trust Secureframe for automated privacy, security and compliance. Click here to set up a demo. Mention “Not Boring” during your demo to get 20% off your first year of Secureframe. Promotion available through October 31, 2022. Hi friends 👋, Happy Monday! I’m baaaaackkkkk. I was a little nervous to take a month off, but I’m really happy with the decision. It was awesome getting to spend a month of family time, and everything they tell you about how wild it is trying to wrangle two kids is true. Puja, Dev, and Maya are all happy and healthy, you’re all still here, and I couldn’t be more excited to dive back into Not Boring, recharged if not rested. To kick things back off, I decided to go where I feel most comfortable: in unfamiliar territory. It’s become clear over the past few months that writing about tech, markets, and the future is impossible without some understanding of macroeconomics, geopolitics, and energy. “We make apps and the world laughs” is the tech equivalent of “We make plans and God laughs.” Since we’ve been away from each other, let me remind you: I’m an idiot, and there are people who are a lot smarter on every topic that I write about than I am. I try to read and talk to as many of them as possible to inform what I write, but especially when we’re talking about topics as big as we’re talking about today, I’m going to miss a lot of nuance, and probably get some things wrong. We’re learning together. But Not Boring’s mission is to make the world more optimistic, and I think that to understand what’s coming next and why things might be better than they seem, it’s important to venture into the great unknown. Progress in the coming decade and beyond will be dictated by energy, atoms, and bits, and most importantly by how we humans use them. We’ve focused a lot on bits in Not Boring, and will continue to – both on their own and in combination with atoms – and today’s piece is a first attempt of many to understand how they’ll all work together to kick off the next wave of growth. Let’s get to it. Working Harder and SmarterThere’s this incredibly dumb twitter debate that roars out of hibernation every few months about whether or not people have to work a lot to succeed. Someone tweets something like, “You need to work hard, including nights and weekends, to succeed in your career.” Most recently, this very cute (since deleted) tweet set off a firestorm: Thousands upon thousands of people were seemingly tremendously offended that a young startup would be evil enough to filter for people who want to work really hard during the critical first stage of the company’s life. Oven (Bun) was the focus of the mob’s incredulity this time, but the response is the same every time:

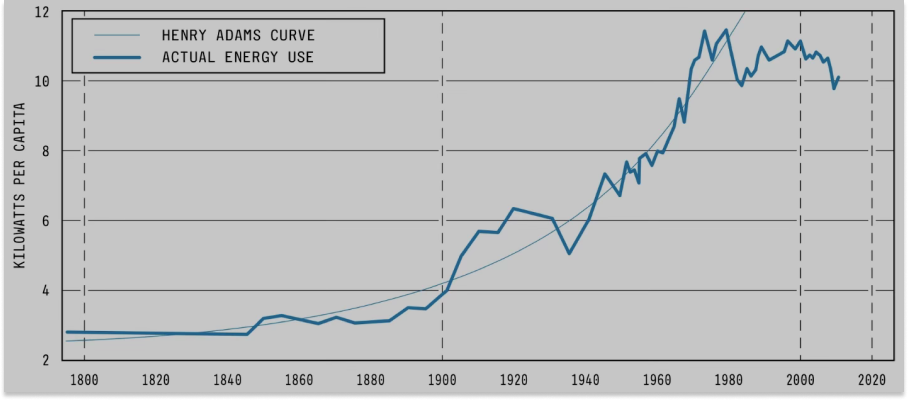

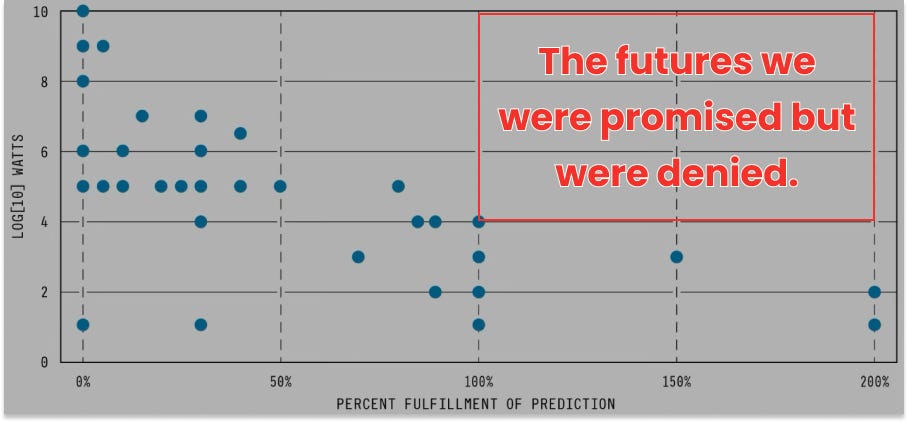

I actually started writing a post taking a stand on the side of hard work after reading the reactions to Oven’s tweet right after watching The Bear… … but there’s no margin in jumping into that argument. People have picked their sides. People like getting riled up. This debate is just a vessel for that. Plus, it’s a dumb debate because there’s a clear winner: the answer is that to build anything worldchanging, you need to Work both Smart and Hard. It is perfectly fine to not want to build something worldchanging, and it’s perfectly fine to question which companies even have a shot at making that kind of impact – certainly, the worldchanging rhetoric has been co-opted by countless startups that aren’t deserving of it – but in those few cases where the thing you’re building is truly going to Change the World™️, there’s no doubt that it will require Hard, Smart Work with a healthy dollop of luck on top. Anyway, like I said, I don’t want to get into that debate. The reason I bring it up is that it’s a good framing for a question I’ve been thinking a lot about. In my last essay pre-Maya, Amplified Tribalism, I wrote about another debate taking shape – physical versus digital – and that I wanted to spend time on paternity leave putting my finger on why that dichotomy was also dumb. Instead of just physical abundance or a purely digital future, I want a combination of both: an Abundance Renaissance. As a quick and dirty shorthand, think about the Abundance Renaissance as the lovechild of the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and the Industrial Revolution, born into the 21st Century. That’s lofty, and it’s going to take Hard Work, Smart Work, and luck for it to happen. So let’s use the Hard Work versus Smart Work argument to frame it up. The debate is both symptomatic of today’s feeling of stagnation, and metaphorical for the arc of progress. Symptomatic because there’s no progress without hard work, which is well understood by at least rational people. The fact that hard work is controversial – particularly when the hard work involves typing on computers in air conditioned rooms, often now at home, doing something that you opted into because it’s either something you love or that you think will make you the most money or both – is a sign of the decadence described by Ross Douthat and the lack of seriousness described by Katherine Boyle. It’s antithetical to progress when the low-hanging fruit has been picked and the biggest remaining challenges and opportunities are really big and really complex. In the coming years, we’re going to see the cultural pendulum swing back from Quiet Quitting to Hard Work. But that’s too on the nose. Of course we need to Work Hard to unlock the next level. You think I’ve been cooking in the lab, not writing the past month, and coming back with a post admonishing you to work harder? C’mon. What I think is less discussed, and more interesting, is that the Work Hard versus Work Smart debate is a metaphor for the arc of human progress, and that an Abundance Renaissance can come about only if we metaphorically Work both Hard and Smart. Luckily, I think we’re on the precipice of the first time in human history during which humanity is able to simultaneously Work Hard and Smart. I’ll start to explain, starting with two charts. Two ChartsThe two charts come from J. Storrs Hall’s Where Is My Flying Car? and, taken together, are among the most striking I’ve come across in a long time. The first shows the Henry Adams Curve. The Henry Adams Curve is the long-term trend of about 7% annual growth in “usable energy available to our civilization,” which “can be factored into a 3% population growth rate, a 2% energy efficiency growth rate, and a 2% growth in actual energy consumed per capita.” Since the scale in this chart is power per capita, the Henry Adams Curve, the light blue line in the chart below, shows only the 2% annual growth in energy usage per capita component, and the dark blue line shows actual energy use per capita. After nearly two centuries of fitting the curve, per capita energy usage fell off a cliff in the 1970s and then flatlined. If you have your capital-E Environmentalist hat on, that might be cause for celebration. If you have your progress hat on, it might be cause for despair. There’s a question / mystery in the Progress Studies community succinctly summarized by the name of the website WTF Happened In 1971?. A bunch of economic charts that went up and to the right suddenly dropped and/or flatlined in the 1970s. There are a bunch of explanations. Declining per capita energy usage, while it fell off a couple years after 1971 with 1973’s Oil Embargo, seems like one of the best. Obviously, though, there has been some wild progress since the 1970s. Here, it’s useful to look at the second chart. This one shows which predictions made by scientifically-inclined sci-fi writers in the first half of the 20th Century came true, and which didn’t, based on their energy intensity. It’s striking. What it highlights is that sci-fi writers’ predictions about things that require 10 kilowatts (kW) or less of energy had a good shot of coming true – with a cluster at 100% prediction fulfillment, and even a couple at 200% prediction fulfillment – but that none of their predictions that would have required 100kw or more of energy came true. “That top right half,” Hall wrote of the quadrant above 10kW and 100%, “represents the futures we were promised but were denied. Including flying cars.” According to Hall, the chart explains that progress continued robustly in one area – “Moore’s Law in computing and communications” – in which energy isn’t a major concern, but flatlined in the energy-intensive, atoms-based areas that made up so much of the progress up until the 1970’s. The history of human progress up until the 1970s was largely about enhancing our bodies’ capabilities, using new power sources, methods, and materials to create more physical things more quickly and cheaply. As Bill Gates’ favorite author Vaclav Smil writes in How the World Really Works, “In two centuries, the human labor to produce a kilogram of American wheat was reduced from ten minutes to less than two seconds.” As a result, the share of the US population working as farmers declined from 83% in 1800 to 1% today. In other words, new energy sources and materials gave humans a way to Work Harder. The past fifty years’ progress has primarily been about enhancing our brains’ capabilities, using new computers, algorithms, and modes of communication to create more digital things and connect over 4 billion people to the internet. Smil doesn’t provide similar statistics for information, but there’s an equivalent here, something like, “In 50 years, the brainpower needed to find a piece of information was reduced from an hour (going to the library, finding a book, finding the information in the book) to less than two seconds (a Google search).” As Google’s Eric Schmidt said way back in 2010, “There were 5 Exabytes of information created between the dawn of civilization through 2003, but that much information is now created every 2 days.” While the veracity of the claim is debated, the general point stands. With computers, humans are capable of Working Smarter. And yet, despite the digital progress, many very smart people agree with Tyler Cowen in his assessment that over the past fifty years, America has been living through The Great Stagnation. Perceived StagnationOne of the best recent encapsulations of that view comes from Tanner Greer of Scholar’s Stage, who asked Has Technological Progress Stalled? in early August. You should read it. Based on an earlier book of Smil’s, Energy in Nature and Society, Greer came to believe that:

If we’re simply Working Smarter and not putting more energy to human use, the logic goes, then we’re not really producing meaningful economic activity. Smil’s position, with which Greer agrees, is that we’re still coasting off the technical innovations of the period between 1867-1914 – “automobiles, electrification, steel beams, and so forth” – and that part of what the fuck happened in the 1970s is that we had just run out of gains from that period’s inventions to harvest. “The fruits of innovation,” Greer writes, “were not so much ended as expended.” Greer concludes his essay by arguing that:

I agree with the idea that we need more energy, materials, and modes of transportation – something that Hall espouses in his book, too – but vehemently disagree on information age technologies’ role in making those things come to life. The perception of a Great Stagnation over the past 50 years could be described as a shift from Working Harder (more energy usage, more atoms innovation) to Working Smarter (better computing, more bits innovation). My hunch is that there’s been a feeling of Stagnation because the benefits of atoms-based innovations are the kind that make more people feel richer and happier than bits-based innovation alone. Getting a refrigerator, car, color TV, or airline ticket for the first time is persistently life-changing in a way that’s hard for an app to be. We need to build more physical things – houses, flying cars, faster planes, affordable cures for diseases, spaceships, and much, much more. But neither Hard Work nor Smart Work can meet the challenge alone. If the low-hanging fruits from the last boom have been picked, we need to create a new boom. How are we expected to invent new materials, modes of transport, and sources of energy without tapping into the improvements in organization and information we’ve harnessed over the past 50 years? The next stage of atoms-based innovation will be harder and more complex to unlock than the last. The sweet spot, as ever, is working both Harder and Smarter. We need to create and consume more energy, not less. And we need to combine atoms-based innovation with the five decades worth of progress we’ve made in the world of bits. So how to reverse the trend? While countless factors played a role in material stagnation – from bureaucracy and regulation to specialization and increasing complexity – I like Hall’s Henry Adams Curve and Sci-Fi Predictions Chart’s focus on energy. It’s simple to pick and optimize for one variable, and energy usage is relatively easy to measure. Let’s focus on energy. For our purposes, more cheap, clean energy consumption is good, less cheap, clean energy consumption is bad. (Of course, if we just try to maximize this variable by any means necessary, we’re no better than the paperclip-producing AI. This post, for example, argues that Bitcoin mining will get us back on the Henry Adams Curve, and if we consume that much more energy just to mine Bitcoin, I uhhh don’t think it will have been a success.) Luckily, we’re on the cusp of an energy transition. New energy paradigms create entirely new ecosystems around them. Steam engines enabled steel, railroads, skyscrapers, and even corporations. Fossil fuels powered cars, planes, polymers, plastics, and booming globalization. Abundant clean energy, too, will reshape cities, transportation, and even the global balance of power, but it will require the best of our bits innovation to maximize its potential and coordinate the potentially more distributed systems it makes possible. I think that if we don’t fuck it up (which, we’re human, so we might), we have a shot at an Abundance Renaissance that combines Working Harder (more energy usage) with Working Smarter (better computing technology) at a scale we’ve never been able to reach in human history to date. If The Great Stagnation isn’t over yet, it’s about to be. So let’s dig into that energy transition. Energy and AtomsWhoever was responsible for clean energy’s branding over the past couple decades needs to be fired and potentially tried for crimes against humanity. Clean energy isn’t about efficiency and replacing dirty fuels with clean ones. It’s about being able to do more and better, creating material abundance and distributing it more evenly across the world, and moving past the long stage of human history in which we fight each other for scarce resources and squabble over petty things out of a sense of scarcity-induced frustration. It’s about getting back on, and even ahead of, the Henry Adams Curve without fucking the planet. Fortunately, despite the awful branding, the Clean Energy Transition seems to be happening right under our noses, and is picking up steam thanks in part to the impacts of the War in Ukraine. In this section, we’ll cover:

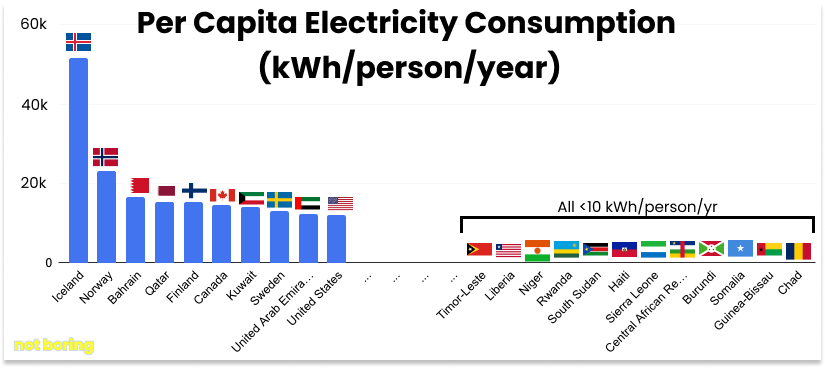

Energy is WealthLet’s start with something that should be apparent, but has been downplayed in the push for efficiency: energy is really important. Energy lets humans “Work Harder” while actually doing less manual labor ourselves. This 2016 post calculated that each American has the equivalent of “nearly 600 full-time ‘human energy servants’” thanks to energy consumption. Even the most ardent Hard Work supporters would never argue that people should work 14,400 hours per day, but that’s the leverage that energy gives us. And that “Hard Work” can work wonders for an economy. An overly simple way to think about a country’s wealth is the amount of energy each of its citizens is able to consume. As a quick sanity check on that claim, here’s a chart of the countries in the world ranked by per capita kilowatt hours (kWh) consumed per year. There’s nuance here. Iceland’s electricity consumption, for example, looks so much higher than everyone else’s because, thanks to its cheap and abundant geothermal energy, it’s become the de facto aluminum smelting capital of the world, which drives up its energy consumption (while keeping its CO2 emissions per capita much lower than the United States or China). But that in and of itself is an argument for abundant clean energy as a strategic priority; Iceland has been able to attract large multinational companies, with their money and jobs, because of it. As a piece of personal anecdata, I got the chance to catch up with my old Au Pair, Gry, a few years ago because of the effects of this chart. Gry is from the #2 country on this chart, Norway, and she and her husband came to visit New York City because it was cheaper for them to fly to the US and buy their Christmas presents in our most expensive city than it was to buy them in Norway. That blew my mind. They were essentially trading their country’s energy riches for our country’s goods. Overall, that chart looks like a good proxy for wealth. The countries with the most energy consumption per capita are countries you’d expect to see at the top of a wealth list – Iceland, Norway, Bahrain, Qatar, Finland, Canada, Kuwait, Sweden, United Arab Emirates, and United States – and the countries with the least are the ones you’d expect to see at the bottom – Chad, Guinea-Bissau, Somalia, Burundi, Central African Republic, Sierra Leone, Haiti, South Sudan, Rwanda. Any big diffs between the per capita energy consumption list and the per capita GDP list seem to largely be accounted for by small populations and business-friendly regulations: Lichtenstein, Monaco, Luxembourg, Bermuda, Ireland, Switzerland, Cayman Islands, and Singapore are all countries with higher GDPs per capita than the US without natural energy advantages. They’re also all tax havens. With the enormous caveat that I’m not an energy or macroeconomics expert, and that I’m sure I’m dramatically oversimplifying in a way that would make real experts throw up, energy abundance seems to be a pretty clean way to think about economic abundance. That point, and the paragraphs supporting it above, are so obvious-sounding when you write them out that it seems almost silly to waste the ink (and your time) on them, but personally, even though my first real job was on an energy trading desk, it’s one that I hadn’t really given much thought to recently. The defining narrative of the past decade when it comes to energy is that we need to use less of it, not more. That narrative is shifting. To read about the Energy Narrative Shift, the Clean Energy Transition, and what it might look like to Work Harder and Smarter…Thanks to Dan for editing, and to our friends at Secureframe for sponsoring! That’s all for today. Catch you on Thursday for a special Founder’s Letter. Thanks for reading, Packy If you liked this post from Not Boring by Packy McCormick, why not share it? |

Older messages

Weekly Dose of Optimism #11

Friday, September 9, 2022

Abolish NEPA, Diablo Days, Interracial Marriages, GUTS, and Abundant Robots

Weekly Dose of Optimism #10

Friday, September 2, 2022

Artemis I pt. II, EVs & Batteries, Seabed Mining, Intelligent Tools, Passion & Pain, and Dude Where's My Flying Car?

Weekly Dose of Optimism #9

Friday, August 26, 2022

Fermi's Responsibility, Chinese Research, Forever Chemicals, Heated Hydrogen, and the Golden Age of AI

Techbio Taxonomy

Monday, August 22, 2022

A guest post by Elliot Hershberg on the four forces reshaping biotech startups

Weekly Dose of Optimism #8

Friday, August 19, 2022

Universal Vaccines, Cancer in the Cold, High-Skilled Immigration, The Immigration Flywheel, and the Europeans Come Back to Nuclear

You Might Also Like

Amazon Reveals It Had 20.93 Billion Searches in December - CrewReview

Friday, February 28, 2025

You're an Amazon whiz... but maybe not an email whiz. Omnisend makes setting up email for your brand as easy as click, drag, and drop. Make email marketing easy. Hey Reader, Believe it or not,

How AI Search Handles Citations, Google’s Latest Lawsuit + 2 Weird Niche Sites

Friday, February 28, 2025

It's Friday and that means one thing... ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Social care strategy, ads scaling tips, background carousels, and more

Friday, February 28, 2025

Today's Guide to the Marketing Jungle from Social Media Examiner... presented by social-media-marketing-world-logo The weekend is almost here, Reader! Before you unplug, here's one last round

Bitcoin industry insiders aren’t worried about the price correction

Friday, February 28, 2025

Today's letter features a guest post from Phil Rosen, the co-founder of Opening Bell Daily, an independent financial media company. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

OpenAI’s underestimated us!

Friday, February 28, 2025

Altman admits they ran out of GPUs—what now?

Influence Weekly #378 - YouTube Star MrBeast Is Raising Money at a $5 Billion Valuation

Friday, February 28, 2025

GTA Developer Explores Partnerships With Metaverse Creators To Transform Popular Game Into UGC Creative Hub

Weekly Dose of Optimism #133

Friday, February 28, 2025

Pancreatic Cancer Vaccine, Restoring Hearing, Loyal, Atlas, Apple, Coinbase, Lunar Landers ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

VC valuations feel the pressure

Friday, February 28, 2025

AI prompts record VC funding; Kindred Ventures' Steve Jang on AI wearables; Stripe hits $91.5B valuation Read online | Don't want to receive these emails? Manage your subscription. Log in The

Standing on the other side of goodbye

Friday, February 28, 2025

Little moments that make me question: have I moved away or come home? ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

A New EBITDA Adjustment to Drive Business Selling Price (a short video)

Friday, February 28, 2025

THE EXIT STRATEGIST A New EBITDA Adjustment to Drive Business Selling Price (a short video) Click Here to Watch Our Short Video The Key to driving strategic value in the sale of a technology company is