Hi there, it’s Mehdi Yacoubi, co-founder at Vital, and this is The Long Game Newsletter. To receive it in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

💌 Last week, we got featured on Substack, leading to an unusual spike in subscriber growth. Welcome to all the new The Long Game subscribers!

In this episode, we explore:

Declining sperm count

Better off not knowing

Bad days

Staying positive

Let’s dive in!

I finally got to read this article about declining sperm count that I had on my list for a month. It didn’t disappoint.

Is Sperm Count Declining?

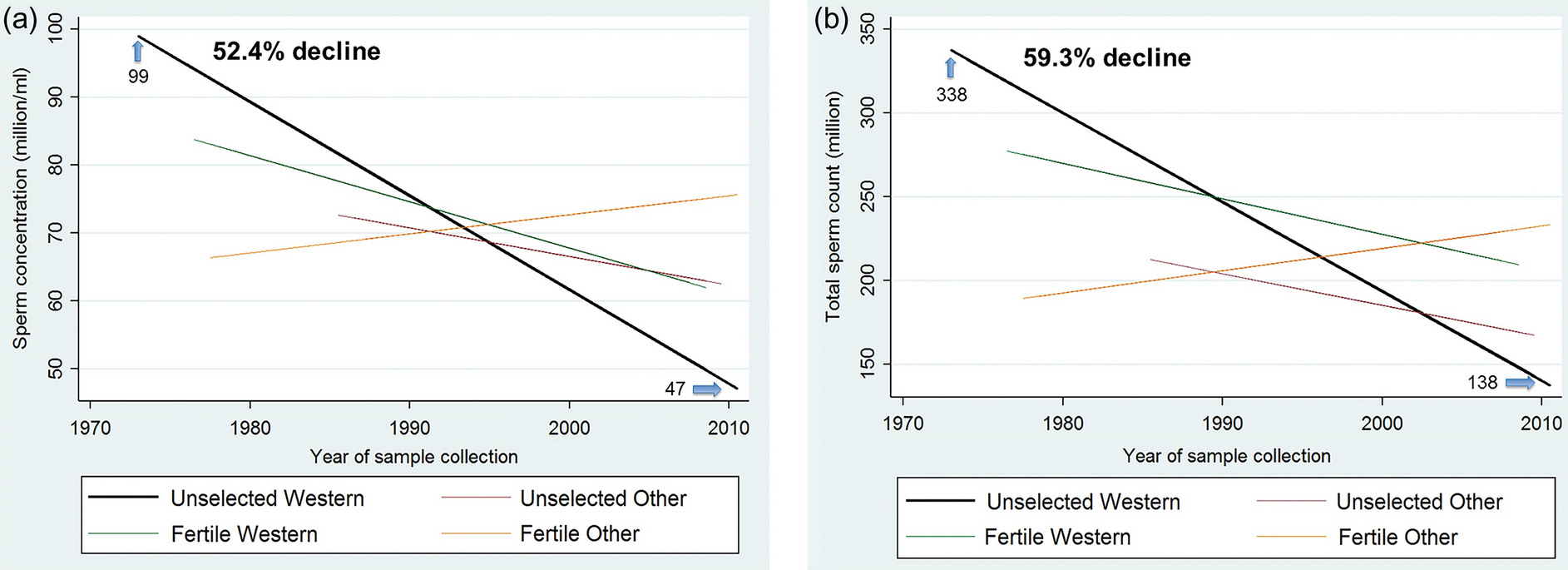

Levine et al 2017 looks at 185 studies of 42935 men between 1973 and 2011, and concludes that average sperm count declined from 99 million sperm/ml at the beginning of the period to 47 million today.

Levine et al 2022 expands the previous analysis to 223 studies and 57,168 men, including research from the developing world. It finds about the same thing.

The “et al” includes Dr. Shanna Swan, a professor of public health who has taken the results public in the ominously-named Count Down: How Our Modern World Is Altering Male and Female Reproductive Development, Threatening Sperm Counts, and Imperiling the Future of the Human Race.

Is Declining Sperm Count Really "Imperiling The Future Of The Human Race”?

“Levine et al model the sperm decline as linear. If they’re right, we have about 10 - 20 more years before the median reaches the plateau’s edge where fertility decreases, and about 10 years after that before it reaches zero. Developing countries might have a little longer.”

How Long Has This Been Going On?

“The first recorded claim about declining sperm counts was in Nelson & Bunge, 1974. They noticed that sperm counts seemed to be declining since the first good study in 1951. There were some previous small unreliable studies before 1951 (the earliest was 1929) that seemed to get vaguely similar numbers to the 1951 study. So, very speculatively, one might suggest that sperm counts started declining between 1951 and 1974.”

How Sure Are We That This Is Even Real?

There are some important confoudners in those studies:

Where are sperm samples coming from? Some people give samples because they are sperm donors, others because they are infertile and want to figure out why.

In the old days, when this was groundbreaking research, most studies were done in cutting-edge research centers in wealthy regions of advanced countries. These places tend to be healthier and have higher sperm counts.

Sperm count is affected by age - if your area’s population is aging, that will change its average sperm count from year to year.

Different countries (and, in the US, different races) seem to have different sperm counts. If your community’s demographics are changing (eg immigration), that might change its average sperm count.

After ejaculation, sperm count decreases and takes a while to build back up again; if your community’s ejaculation frequency is changing (eg people have gained access to online porn), that will change its average sperm count.

Where Is The Decline Most Pronounced?

Auger et al report that they found declining sperm count in:

If Sperm Count Is Declining, What Could Be Causing This?

The main hypotheses so far:

Plastics (endocrine disruptors)

Pesticides (endocrine disruptors)

Sunlight and circadian rhythm

Diet and obesity

Porn

Some other possibilities:

Marijuana decreases sperm count and people use it a lot more recently

Sitting decreases sperm count and more people have sitting jobs

Cell phone in your pocket

Heat is known to decrease sperm count, are we getting more of it for some reason? Global warming? Heated buildings? Laptop on your scrotum?

Women are using hormonal birth control, and men are either absorbing it through the water supply, or missing cues of fertility that would otherwise increase sperm production through to some galaxy-brained evo psych daisy chain.

Conclusion

“To grind my usual axe: this is the kind of complex issue that makes me wary of bias arguments and the “misinformation” framing.

If it turns out this was real all along, people will point to the hundreds of studies demonstrating it and prestigious scientists pushing it. Doubters will be compared to global warming denialists, ignoring science in order to continue their fantasy of consequence-free pollution.

And if it turns out this was totally fake, people will talk about how this was a classic panic of fragile masculinity (“our precious bodily fluids!”). They’ll place it alongside ivermectin in the annals of “don’t trust small noisy studies”.

In retrospect, it will feel obvious that one side was right all along and the other was laden with junk science, biases, and all the classic red flags for conspiracy theories. We’ll be told we should have “trusted the experts” - either experts like Levine and Swann saying it’s real, or experts like Auger and Fisch saying it’s overblown.

But right now, not knowing which side is right, we don’t have any of these easy outs. We have to actually reason under uncertainty!”

Pair with: Countdown & Endocrine Disruptors

I stopped reading the news a long time ago. Now my primary source of information is Twitter, but I tend to curate my timeline aggressively to remove the things I don’t want to see and keep it positive.

This article greatly explains why being plugged into the news is so bad for you.

For many Americans, these claims sound self-evidently true: Information is good; knowledge is power; awareness of social ills is the mark of the responsible citizen. But what if they aren’t correct? Recent studies on the link between political awareness and individual well-being have gestured toward a liberating, if dark, alternative. Sometimes—perhaps even most of the time—it is better not to know.

Like taking a drug, learning about politics and following the news can become addictive, yet Americans are encouraged to do more of it, lest we become uninformed. Unless you have a job that requires you to know things, however, it’s unclear what the news—good or bad—actually does for you, beyond making you aware of things you have no real control over. Most of the things we could know are a distraction from the most important things that we already know: family, faith, friendship, and community. If our time on Earth is finite—on average, we have only about 4,000 weeks—we should choose wisely what to do with it.

What the writer Sarah Haider calls “information addiction” is nothing short of an epidemic. In a quite literal sense, politics is making Americans sick. But the sole way to contract the illness is by seeking out the news and consuming large amounts of it. And that’s a choice. Haider chose differently, deciding to go news free for six months in late 2021 and early 2022. Having missed out on stories that were speculative, overhyped, or irrelevant, she reported being “saner, happier, and (surprisingly) more informed.” But does it make sense for other Americans, perhaps millions of them, to completely rethink their relationship to political information and knowledge? In a 2022 study, the political scientist Kevin Smith estimated that between 50 million and 85 million Americans suffer from politically induced fatigue, insomnia, loss of temper, and impulse-control problems. Moreover, 40 percent of his sample of American adults reported that politics was a “significant source of stress” in their lives, while 5 percent—which would translate to roughly 12 million people—reported suicidal thoughts due to politics.

I forgot where I read this idea, I’ve been looking for it this weekend but couldn’t find it (maybe James Dyson or Steve Jobs? Let me know if this rings a bell to you!). It goes along the line of (paraphrasing):

On your bad days, do everything you can to cut your losses. Problems tend to come in groups, so it’s essential to recognize the days when everything can go wrong.

Once you recognize such a day, what can you do? I’d say close everything you’re doing, cancel your meetings and go for a long walk. If the good energy came back, this day could be turned into a good one; otherwise, call it a day!

It’s tempting to try to fix the issues at hand immediately, but this can often backfire if you’re not in the right set of mind.

A timeless piece from Fred Wilson I like to revisit from time to time:

One of the gifts that I got was the ability to stay positive. I am grateful to my parents, my wife, and my genes (and anyone else responsible too). It is such a superpower.

I don’t just mean optimism. I mean saying nice things about people. I mean keeping a smile on your face. I mean positivity in all things. I do have my moments of negativity, but they come infrequently and go away quickly.

I saw Magic Johnson say something nice about the Lakers last night and I texted my son that I appreciate how Magic is always so positive. He always has a smile on his face. He is always saying nice things. I am sure he was a vicious competitor on the court, but he did it nicely.

I recall when David Karp was building Tumblr, he refused to have comments. He refused to have downvotes. The only user engagement was a heart and a repost. He told me he wanted to emphasize positivity and de-emphasize negativity. And Tumblr was a very positive place to be during its heyday.

For every negative thought, there is a positive counter thought. If you don’t like the Celtics, maybe you like the Knicks. If you don’t like Trump, maybe you like Biden. If you don’t like Bitcoin, maybe you like Ethereum. It is a pretty simple move, and also a very powerful move, to focus on what you like versus what you don’t like.

Doing this not only can change how others feel about you, it can change how you feel about yourself. I highly recommend it. I hope it becomes a trend. We would all be happier and nicer. Social media would be tolerable. Life would be better.

for one thing, be annoying

Just Do Simple Shit

Almost nobody is beyond feeling good when you say “good job” or “I love this” or “nice work” or give them an upvote on some social media platform or share their stuff. This is a free way to sculpt the world in the ways you’d like it to be sculpted. Do this liberally. If you think this is too elementary for you, or that it would harm the veneer of sophistication that your social media account tries to project, get over yourself.

Be Willing to Be Slightly Annoying, Sometimes

Annoying people a lot isn’t productive, most of the time. Being willing to annoy other people a little bit at the right times, on the other hand, is a useful social skill. Sometimes, annoying people a bit is the cost of being vehement, and the benefits can outweigh the downsides. For example: I have heard that, occasionally, Alexey Guzey will essentially show up at someone’s house and refuse to leave unless they finish something they’ve been postponing. I have heard this from people who were extremely grateful to Alexey for doing this, although at the time they were slightly annoyed.

There are a few talented writers who are internet acquaintances of mine, who don’t always produce work at the volume they say they want to. So, I make a point of harassing them about it on WhatsApp or email now and again. I am sure that this has annoyed some of them at least slightly. On the other hand, they are now producing more work. This is a tradeoff that I’m happy with. Sometimes people need affirmation, even if they don’t like that they need affirmation. There are surprising examples of this. Karl Ove Knausgaard needed a friend to tell him, continuously, through the writing of My Struggle, one of the most celebrated literary works of the last few decades, that it was good and interesting.

Dan Wang’s annual letter. As always, a must-read.

Mountains offer the best hiding places from the state.

There were a lot of state controls to escape from in 2022. Two days before Shanghai locked down in April, I was on the final flight from the city to Yunnan, the province in China’s farthest southwest. Yunnan’s landmass—slightly smaller than that of California’s—features greater geographic variation than most countries. Its north is historic Tibet, while the south feels much like Thailand. People visit the province for its spectacular nature views: rainforest, rice terraces, fast rivers, and snowy mountains. Otherwise tourists are drawn to its ethnic exoticism. As many as half of the country’s officially-recognized ethnic groups have a substantial presence there, including many of those that have historically resisted Han rule.

As Shanghai’s lockdown became protracted, a trip planned to last days grew into one that lasted months. Wandering through Yunnan gave me a chance to contemplate the culture of the mountains.

31 maxims from François de La Rochefoucauld (1613-1680)

4. “Moderation is a fear of falling prey to the envy and disdain that those who are enraptured by their own good fortune deserve: it is a vain and ostentatious display of our mental strength; and finally, the moderation of men at the height of their eminence is a desire to appear greater than their good fortune.”

Reminds me of upper-middle class people talking about how expensive everything is. Pulling out their little glasses at restaurants, carefully scrutinizing every item on the bill like an accountant.

5. “It takes greater virtues to bear good fortune than bad.”

6. “We often pride ourselves on our passions, even the most criminal ones; but envy is a timid, shamefaced passion, which we never dare to acknowledge.”

Of the “seven deadly sins,” envy is the one people are least likely to own up to.

7. “Our evil deeds do not bring on us as much persecution and hatred as our good qualities.”

8. “If we had no faults, we would not derive so much pleasure from noting those of other people.”

30. “The sure way to be deceived is to think yourself more astute than other people.”

31. “We all have enough strength to endure the misfortunes of others.”

It’s not the homework. It’s the phones.

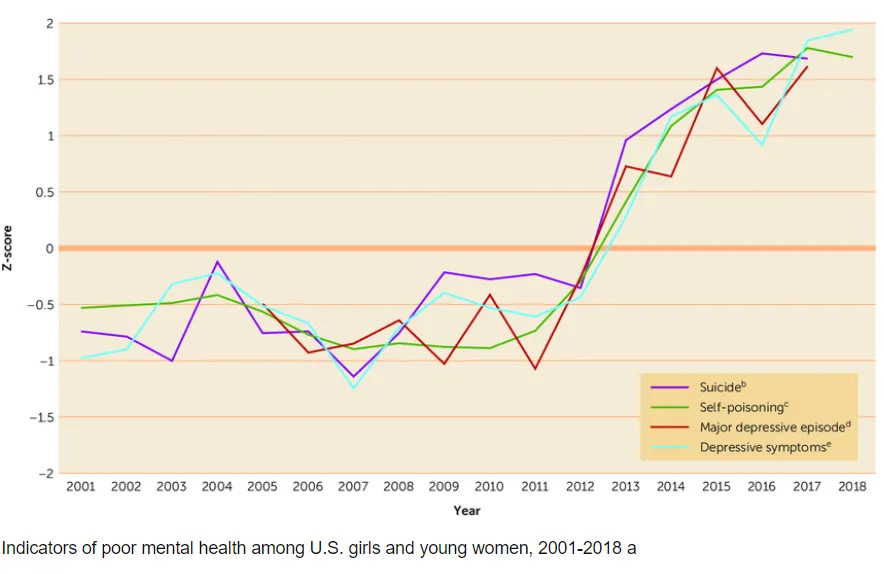

That leaves us back where we started: The main suspect in the teen mental illness epidemic is still smartphones and social media. Unlike homework time and academic pressure, time spent online and on social media increased enormously while teen depression (and loneliness) was rising, and experimental evidence points to a causal role for social media use on teen depression, as Jon showed in a previous post. Averaging across 2018-2021 in Monitoring the Future, 22% of 10th-grade girls said they spent seven or more hours a day using social media. How can that not have a significant impact?

Derek Thompson’s story in the Atlantic ends with a quote from psychologist Laurence Steinberg: “Sometimes I just think, my God,” he says about the academic pressure teens face today, “Like, shouldn’t we care about giving kids a good experience of being a kid?”

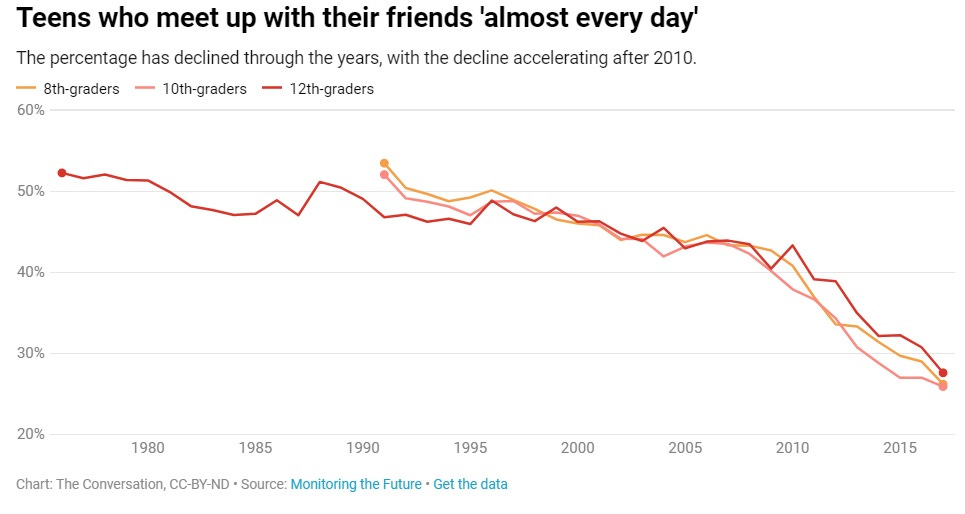

Yes, we should – and that means making sure kids aren’t getting sucked into an addictive activity, giving their lives away to social media companies and becoming depressed because of it. Kids should be out socializing a lot more. Social media is one of the main reasons they are doing less of that than ever.

Artificial intelligence never needed to evolve, so it didn’t develop the survival instinct that leads to the impulse to dominate others.

As we teeter on the brink of another technological revolution—the artificial intelligence revolution—worry is growing that it might be our last. The fear is that the intelligence of machines will soon match or even exceed that of humans. They could turn against us and replace us as the dominant “life” form on earth. Our creations would become our overlords—or perhaps wipe us out altogether. Such dramatic scenarios, exciting though they might be to imagine, reflect a misunderstanding of AI. And they distract from the more mundane but far more likely risks posed by the technology in the near future, as well as from its most exciting benefits.

Takeover by AI has long been the stuff of science fiction. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, HAL, the sentient computer controlling the operation of an interplanetary spaceship, turns on the crew in an act of self-preservation. In The Terminator, an Internet-like computer defense system called Skynet achieves self-awareness and initiates a nuclear war, obliterating much of humanity. This trope has, by now, been almost elevated to a natural law of science fiction: a sufficiently intelligent computer system will do whatever it must to survive, which will likely include achieving dominion over the human race.

To a neuroscientist, this line of reasoning is puzzling. There are plenty of risks of AI to worry about, including economic disruption, failures in life-critical applications and weaponization by bad actors. But the one that seems to worry people most is power-hungry robots deciding, of their own volition, to take over the world. Why would a sentient AI want to take over the world? It wouldn’t.

Pair with: Let's think about slowing down AI

I found this part of Digital Native’s latest edition worth sharing.

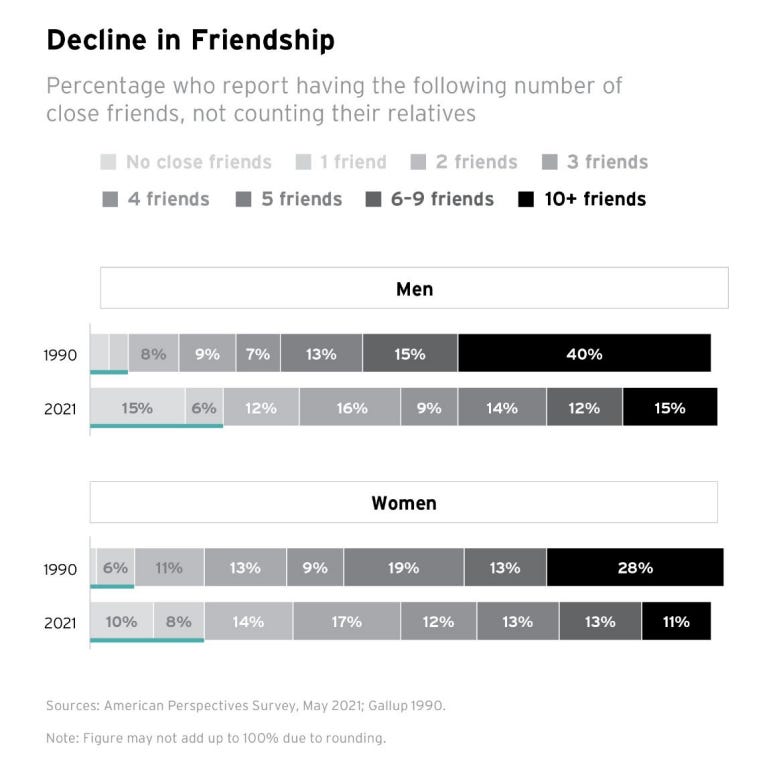

The deterioration in mental health charted above is also connected to a rise in loneliness, again precipitated by technology.

In the last 30 years, the percentage of people with <=1 close friend has nearly tripled to 20% of the population. The percentage of people who report 10+ close friends has dropped from 40% to 15%.

Jean Twenge has also charted social isolation among teens. Again, alongside the rise of smartphones and social media, in-person interaction falls off a cliff.

I saw a TikTok last week from a woman who was devastated because of the 100 people who had RSVP’d “yes” to her wedding, fewer than 40 showed up. She ended up shortening her ceremony and cancelling her reception. It was hard to watch.

Technology is a double-edged sword: it expands our social circles by connecting us with likeminded people we would never otherwise meet. But, uncontrolled, it can also subsume offline interactions, whose richness can’t be replicated digitally. I expect that in 20 or 30 years, we’ll look back at the early days of social media and be aghast at how we let it absorb of our time and crowd out true human connection.

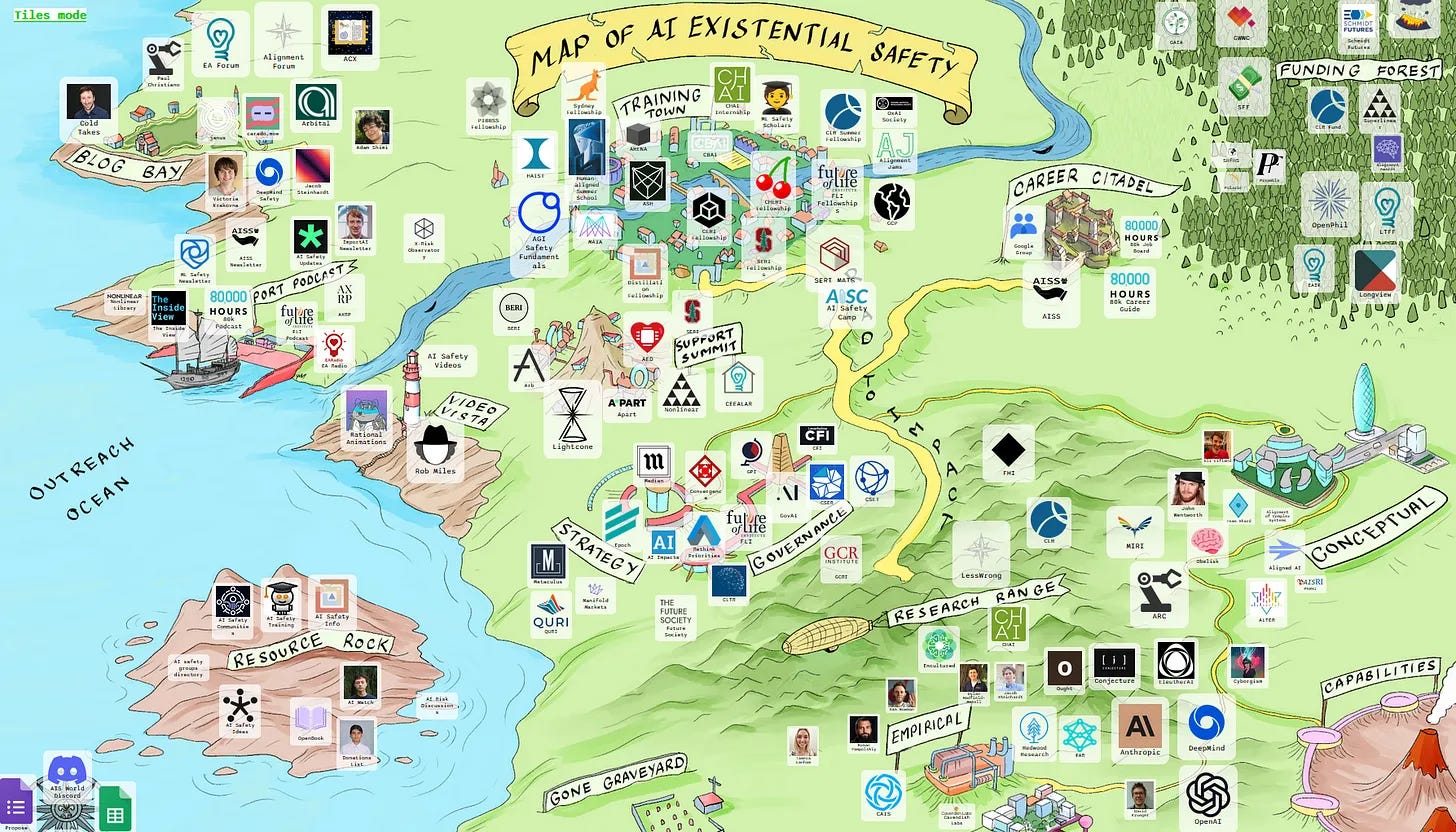

An interactive map to help you understand where different people fall on the topic of AI safety.

Sometimes you need to run your ships aground, burn them, and leave yourself just one option: succeed or go down.

— Robert Greene

Thanks for reading!

If you like The Long Game, please share it on social media or forward this email to someone who might enjoy it. You can also “like” this newsletter by clicking the ❤️ just below, which helps me get visibility on Substack.

Until next week,

Mehdi Yacoubi