Hi there, it’s Mehdi Yacoubi, co-founder at Vital, and this is The Long Game Newsletter. To receive it in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

In this episode, we explore:

Strength training

Lifestyles

Trade-offs

Finding PMF

Nature vs. nurture

Let’s dive in!

A Vital friend asked some great questions that I thought I’d answer here:

Which exercises would be good for a beginner to start with?

It depends if the goal is strength or hypertrophy. For strength, focusing on squat, bench, deadlift + overhead presse & pull-ups will be great. A method like Starting Strength can remove a lot of the guesswork and work well for some.

For hypertrophy that can also work for a newbie (pretty much anything with some intensity will work in that case), but it will quickly limit the amount of muscle mass you’ll put on. At that point, you can start adding more exercises & variations.

Of course, this depends on your goals, and at first, getting stronger will build you a solid base of muscle. For example, taking your bench from the empty bar to 225lb will—without a doubt—build your chest & triceps. However, this mindset has some limits and this is not infinitely scalable. For example, getting your bench from 315 to 405 won’t lead to the same hypertrophy results. Plus, after the initial phase where strength gains are linear, it takes way longer to add pounds to the bar, that’s when leveraging machines, and variations of the main lifts become essential.

What should be the ideal duration and number of repetitions per exercise for a weightlifting session?

1 hour is a good target.

For strength, Andy Galpin’s heuristic is a good one:

3-5 days a week — 3-5 exercises — 3-5 sets — 3-5 reps

For hypertrophy, you can start with a classic Push, Pull, Legs routine (example) or an Upper, Lower (example)

Can you suggest any good resources (blogs, videos, etc.) to learn more about weightlifting and muscle building?

YT Channels:

Alex Leonidas

GVS

Bald Omni Man

Alexander Bromley

Alan Thrall

And for the Mindset™️ (most important imo): Eric Bugenhagen

Do you have any tips for making quick progress?

Stay consistent.

Don’t start too intense.

Learn to love it — it’s the single most important thing to make great progress.

Keep learning.

Play the long game, and do not expect to get “jacked” in less than 5—10 years.

Find programs, and training styles that respect the basics of strength/ hypertrophy and that you enjoy.

If done well, the first two years of training will bring an insane amount of strength & muscle compared to what will come next, so enjoy!

What are some common mistakes that beginners often make when starting with strength training that I should avoid?

Expecting results too fast 😅

Not eating enough, not sleeping enough, not eating enough protein (2g/lb of bodyweight)

Overcomplicating things: keep it simple, train 4+ times per week, intensely, eat, sleep, and recover, don’t worry about what advanced lifters have to worry about, enjoy the simplicity beginners can enjoy

Not doing enough volume at the adequate intensity (shoot for 10—20 working sets per body part per week.)

Doing too much volume, which ends up being junk volume.

Spending 90% of your time on your phone, and not having a single drop of sweat at the end of the workout

Anyway, I could keep going, but it’s funnier on Vital, so join us!

Join Vital

This is an exceptional piece about the different possible lifestyles of today, and why this is a bigger problem than it seems.

Digital technology has increased the number of lifestyles plausibly perceived as viable, simply by increasing the number of people who can project different kinds of lifestyles.

It looks like there are many ways to live a good, happy, successful life:

You can strictly eat nothing but animal organs and become a jacked fitness influencer

You can be a girlboss and live in Manhattan, think about husband and kids later

You can grow wealthy and autonomous by putting all of your worth into Bitcoin

You can grow wealthy and autonomous by doing OnlyFans

You can leave your spouse for no reason and write for The Atlantic

You can also start a normal business, abide by traditional ethical constraints, and go to Church every Sunday

For each of the above, there are real examples you can point to. There are people who have done all of these things, and plausibly appear to be thriving.

The problem is that all of these things are new (one is not, but it's operating under wildly new conditions, so now it is new).

Roughly speaking, nobody has done any of these things—in their contemporary version—for a whole human life cycle.

Thus, I would argue that, right now, people generally underestimate what we might call lifestyle risk.

For example, a lifestyle might look great in the 20s & 30s but the tradeoffs that made it look & feel good lead to a bad outcome in the second part of life (I let you imagine what that could be!)

Here’s another important part of the article, especially for readers of TLG 😅

Even the research-based Healthy Lifestyle crew. Keto and cold plunges could be great, but also maybe they'll kill you for obscure reasons, which haven't entered our dataset yet. Maybe Wim Hof and Andrew Huberman have it all figured out, but their lives aren't complete yet, so we should not be overconfident in their advice. What if living according to legitimately science-based health hacks causes severe problems in other dimensions? Perhaps you lose a certain... je ne sai quoi. But on your deathbed you realize that je ne sai quoi was the absolute key to life, and you missed it.

My point is that, even for whatever lifestyle niche you think is the most indubitably correct, your risk of being badly mistaken is higher than its ever been. Even the most ancient and "lindy" lifestyle heuristics have a higher risk of being wrong today than ever before, simply because the artificially manipulated fraction of the lifeworld is greater than it's ever been. Lindy heuristics might be some of the safest, but it's still possible that one recent change in the artificial environment now requires one important artificial change in one's heuristics in order to survive (or thrive). The lifestyle question now has higher stakes and higher risk across the board, which is not to say equal risk across the board.

I personally started to feel the “Maybe Wim Hof and Andrew Huberman have it all figured out, but their lives aren't complete yet, so we should not be overconfident in their advice. What if living according to legitimately science-based health hacks causes severe problems in other dimensions?” strongly lately.

There isn’t necessarily a simple solution to this new problem, but the author still suggests an interesting idea:

Before all of these massive social experiments finish collecting data, it's hard to know, from a scientific perspective, which lifestyles really are the best today.

But I think it's a good start to recalibrate regarding the real challenge before us, which is not really any of the stuff most people want to tell you about.

If you find it stressful, and ugly, to always be optimizing your strategies and tactics, you should be pleased by my point. If strategies and tactics are your bread and butter, you should be terrified by my point.

If you're currently sitting on a winning lifestyle, meaning that your vital energies are correctly subordinated to whatever value system truly belongs to human nature, but you're using mediocre strategies and tactics, I think you're much more likely to be thriving in 2050 than if you're currently using great strategies and tactics but you're incorrectly oriented.

This, by the way, is why true thinking, patient reading, and obsessively authentic writing and speaking are the most economically valuable things in the world right now, even though they remain relatively illiquid and not many people fully understand yet.

“There are no solutions, there are only trade-offs; and you try to get the best trade-off you can get, that's all you can hope for.”

— Thomas Sowell

I remembered this quote recently and started seeing it everywhere. This a reminder that you can’t have it all and that trying to do so is the quickest way to have nothing at all!

It’s usually a better idea to think of the trade-offs you are willing to make.

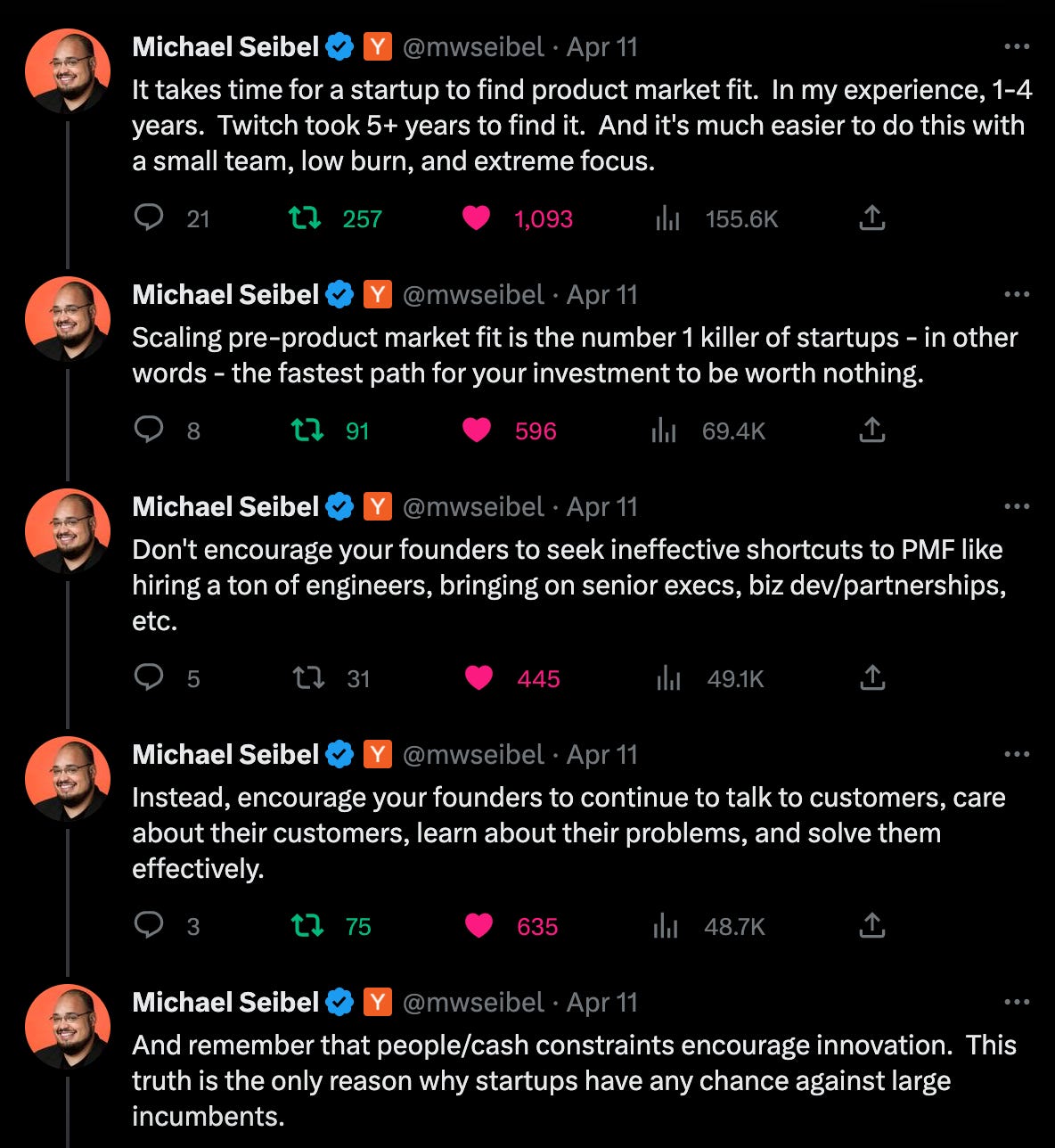

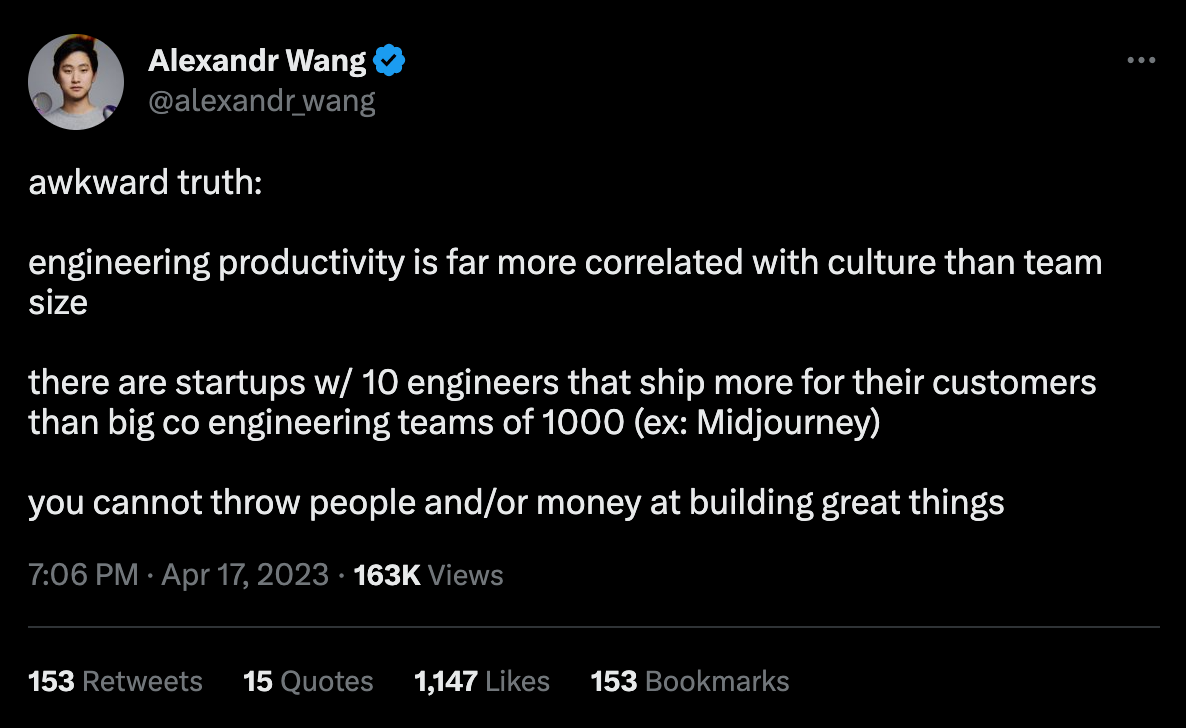

Unfortunately, Twitter doesn’t allow Substack to embed tweets anymore, so forgive the bad-looking screenshots!

I found this thread by Michael Seibel to be very important and worth sharing. It’s very tempting to try to skip steps as an early-stage startup, but there is no such thing. Finding PMF is not something that can be skipped or made extremely fast.

Scaling pre-product market fit is the number 1 killer of startups - in other words - the fastest path for your investment to be worth nothing.

Don't encourage your founders to seek ineffective shortcuts to PMF like hiring a ton of engineers, bringing on senior execs, biz dev/partnerships, etc.

Instead, encourage your founders to continue to talk to customers, care about their customers, learn about their problems, and solve them effectively.

And remember that people/cash constraints encourage innovation. This truth is the only reason why startups have any chance against large incumbents.

PS: Also never let your founders treat you like their boss. This is a natural fear reaction that many founders resort to when they realize how hard reaching PMF truly is. Don't fall for it! It's their company and their job to figure out the hard stuff.

Lastly, another slightly similar idea: more people is rarely the solution to going faster. Very often this boils down to culture.

On nature vs. nurture.

Since the 1960s psychologists have talked about the importance of early attachment. The theory is that if a child has a strong emotional bond with its parents or carers, it develops a sense of security and trust, and that relationship models the way it feels and interacts with others later. So, if you give an infant undivided attention, spend quality time and respond promptly to their needs, they will acquire social competencies and better emotional regulation. One can debate about how universally valid this model is, and whether it applies equally to Western nuclear families and farming communities in Africa where caregiving is an extended family affair. Child-led parenting, especially when you’re doing it alone, often feels like Sisyphean work. Western parents may dream of playing pass-the-parcel with a choir of benevolent aunties expressing their delight in jolly, high-pitched tones. But the benefits of persevering are clear.

A 2021 systematic review of 102 randomised controlled trials across 33 countries, from low- to high-income, concluded that parenting interventions in the first 3 years of life, especially those that emphasised responsiveness to the child’s needs, do indeed improve children’s socioemotional development and cognitive skills.

Six propositions for evaluating the evidence.

I think I have a pretty good record of “prophesying.” Drawing on my research in moral psychology, I have warned about 1) the dangers that rising political polarization poses to American democracy (in 2008 and 2012), 2) the danger that moral and political homogeneity poses to the quality of research in social psychology (in 2011 and 2015) and to the academy more broadly (co-founding HeterodoxAcademy.org in 2015), and 3) the danger to Gen Z from the overprotection (or “coddling”) that adults have imposed on them since the 1990s, thereby making them more anxious and fragile (in 2015 and 2018, with Greg Lukianoff, and 2017 with Lenore Skenazy). Each of these problems has gotten much worse since I wrote about it, so I think I’ve rung some alarms that needed to be rung, and I don’t think I’ve rung any demonstrably false alarms yet.

I’ll therefore label myself and those on my side of the debate the alarm ringers. I credit Jean Twenge as the first person to ring the alarm in a major way, backed by data, in her 2017 Atlantic article titled Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation? and in her 2017 book iGen.

So this is a good academic debate between well-intentioned participants. It is being carried out in a cordial way, in public, in long-form essays rather than on Twitter. The question for readers — and particularly parents, school administrators, and legislators — is which side you should listen to as you think about what policies to adopt or change.

How should you decide? Well, I hope you’ll first read my original post, followed by the skeptics’ posts, and then come back here to see my response to the skeptics. But that’s a lot of reading, so I have written my response below to be intelligible and useful to non-social scientists who are just picking up the story here.

The ideological starting point is that sexism is bad. But how, then, do we reconcile that with benevolent sexism predicting good relationship outcomes?

Benevolent Sexism and Relationship Outcomes

In the case of relationship outcomes, benevolent sexism seems to predict more positive outcomes than negative. Psychologists who research benevolent and hostile sexism treat this as a puzzle. The ideological starting point is that sexism is bad. But how, then, do we reconcile that with benevolent sexism predicting good relationship outcomes? Indeed, much research seems to have been conducted for the express purpose of trying to explain why benevolent sexism predicts positive life and relationship outcomes (Connelly & Heesacker, 2012; Napier et al., 2010).

For example, benevolent sexism is associated with higher relationship satisfaction (Sibley & Becker, 2012; Lachance-Grzela, 2021; Leaper et al., 2022) and less relationship conflict (Leaper et al., 2022). For individuals in relationships, benevolent sexism predicts higher life satisfaction (Waddell et al., 2019) and higher well-being for both men and women (Hammond & Sibley, 2011).

Men who score high in benevolent sexism are viewed more favorably by women (Bohner et al., 2010) and preferred by women (Gul & Kupfer, 2019). Montañes et al. (2013) found that the most attractive men were those high in benevolent sexism. Having more relationship experience also predicted a higher female preference for benevolently sexist men. Cross & Overall (2017) similarly found that benevolently sexist men were more attractive to women, particularly if women desired more relationship security. Adolescent men who were higher in benevolent sexism also had more relationship experience (Lemus et al., 2010).

How Andy Warhol invented nerd culture; why it's imploding.

It’s been about a decade since we killed all the hipsters. The last genocide ever perpetrated against white people. There are mass graves, still, just outside the major cities, places we don’t really want to think about: heaped thousands of hipster skeletons, each still wearing the tufts of its big lumberjack beard, sealed forever in artisanal wax. We lashed the hipsters to their fixies and herded them off a cliff. We burst into the Vice offices in Old Street and hacked them to bits with machetes. We put botulism in all the PBR. We made the hipsters kneel down in front of a wall. Wait, the hipsters said, you don’t have to do this, I’m not really a hipster, there’s actually no such thing as a hipster. That’s great, we said. If you’re not a hipster, then this is not happening to you. And then we pulled the trigger.

We had to do it, you understand. These people left us with no choice. They were very, very annoying.

Now, innocent people sometimes wonder where all the hipsters went. They were everywhere, once, and now they’re gone: what happened? Who killed them? What happened is this: hipsterism as the dominant mode of mass culture could only exist under very specific informational conditions.

It’s destabilizing to have a nation of young strivers with no coherent vision or path to success.

The concept of “elite overproduction” has attracted a lot of attention in the past several years, and it’s not hard to see why. Most associated with Peter Turchin, a researcher who has attempted to develop models that describe and predict the flow of history, elite overproduction refers to periods during which societies generate more members of elite classes than the society can grant elite privileges. Turchin argues that these periods often produce social unrest, as the resentful elites jostle for the advantages to which they believe they’re entitled.

Consider societies in which aristocrats enjoy feudal privileges over land and are afforded influence in government. These sorts of dynastic privileges have been common in world history. Now imagine that over time, the number of people in this class has grown; more and more children of aristocrats means there are more and more people who hold aristocratic status. This creates a math problem: there’s only so much land to divide up and only so many people that can meaningfully guide government. The elites who have been denied their advantaged position in society, sometimes a literal birthright, will often respond to this denial with political and social unrest, and sometimes with violence.

An ai-generated song by Drake & The Weeknd was dropped in the last few days and it went viral (it was since taken down). This was a great analysis by Dave Edwards:

Gonna have a newsletter out on AI + music fairly soon but some thoughts for now;

-UMG has the toughest copyright team around. You couldn’t pick 2 artists who are going to provoke a stronger response than these two. Suspect they’ll drop the hammer on whatever distributor put this on Spotify.

-Everyone running to make AI music is about to discover what artists already know: making something is one thing, driving discovery is another. It’s already nearly impossible to get eyes/ears on your content, and it will only become exponentially harder as more people do this. You’ll of course have outliers like this where the novelty creates virality, but once that wears off, you’re going to be making AI music for an audience of one 99.9% of the time.

-If you’re asking “how can they ban the model” you’re asking the wrong question - you can’t realistically ban code people can run locally. They’ll instead choke off distribution where people discover music on streaming, YT, etc. And that can very much be done.

-I think there are some things to be excited about on the artist tools + AI side, but training a model on someone’s decades of hard work at their craft and uploading it to streaming platforms to get paid yourself is 🤦♂️

-Some artists will lean into this and license their voice to specific models and extract a fee each time it’s used and streamed. I talked about this in Streaming’s Endgame (link in bio) almost 2 years ago and it’s coming for the film industry as well. Lil Nas X blew up from leaning into meme culture; the next Lil Nas may well blow up from leaning into AI licensing. But again, content creation isn’t king - distribution is.

-The music industry won’t be the most impacted by this, film will be. The cost of creating world class music collapsed to $0 a decade plus ago, but it hasn’t for Hollywood - until now. When any kid with an NVIDIA card can create something that looks like a $200M action movie, Hollywood will experience the same thing music has over the last 2 decades.

-We need AI regulation now to ensure publishers, artists, writers, software engineers - or anyone making the content models are trained on - are compensated if they want to be involved and have an opt out if they don’t want to be involved.

-Last one for now: a lot of people are calling this a Napster moment for music; it’s not. AI is a Napster moment for everyone. When music could be stolen in 1999, the same didn’t apply to legal work, accounting, or whatever you may do for a living. That’s different this time. As entertaining as you may find this, consider how entertaining it will be when the same tech collapses your years/decades of knowledge into a prompt soon. And it’s for precisely that reason that I suspect AI regulation will be the biggest topic in DC and elsewhere by second half of 2023.

Witness the beauty of my home country.

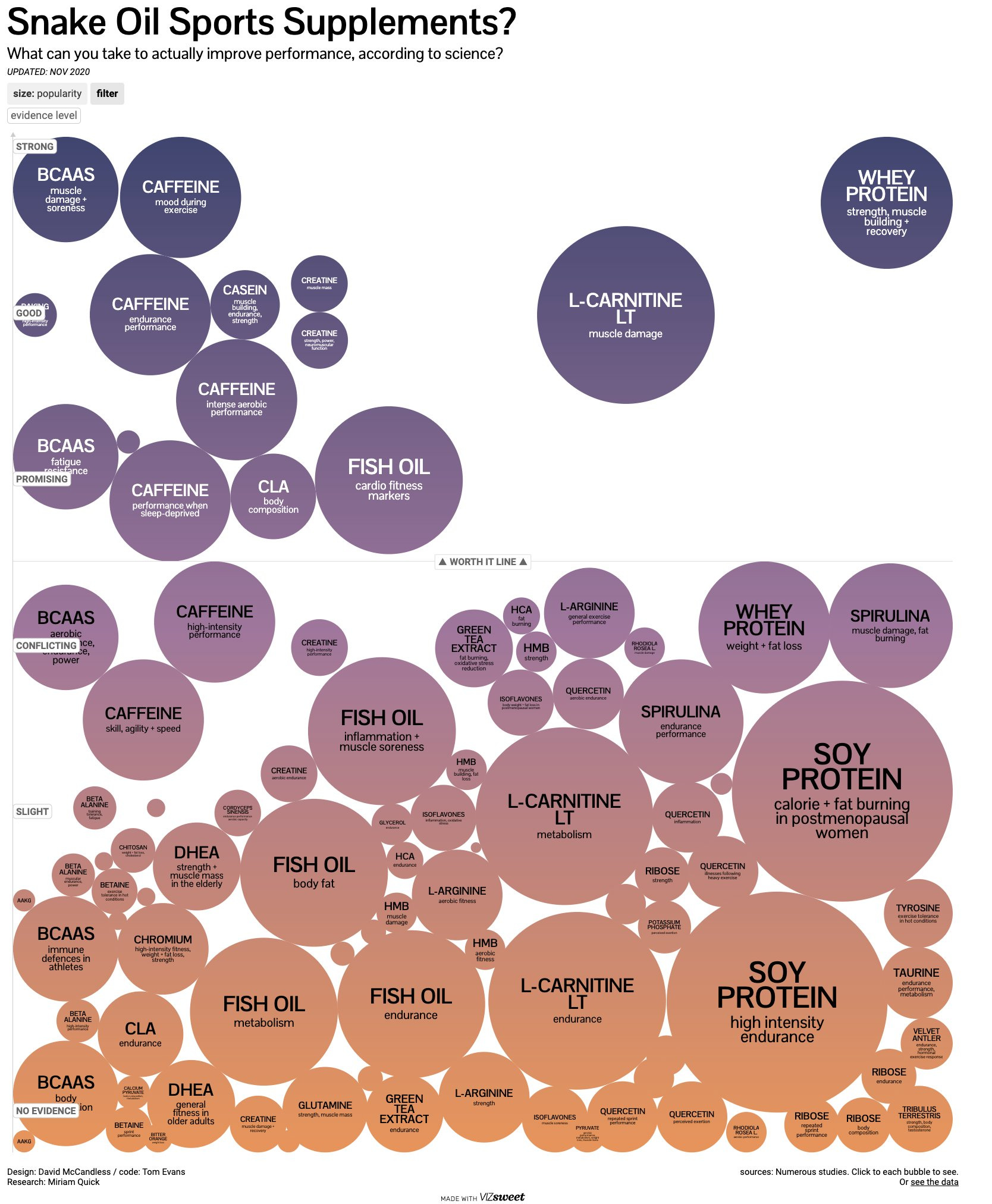

This is an interesting interactive graph to explore which supplements have the strongest scientific evidence level.

What supplements are you taking?

I’m taking vitamin C, magnesium, vitamin D, and whey protein.

"One day I was sitting at home and, I remember having the thought 'You can did this hole as deep as you want to dig it.' I remember thinking 'My God, I'm going to spend the rest of my life in this fucking hole.' You can reach these points in life when you say, 'Fuck, l've reached some sort of dead-end here. And you descend into chaos. All those years you thought you were achieving something. And you achieved nothing. I was thirty-eight years old. I'd just been fired. My second wife had just left me.

I had somehow fucked up. I developed this maniacal passion for wanting to achieve something."

— Jim Clark

Thanks for reading!

If you like The Long Game, please share it on social media or forward this email to someone who might enjoy it. You can also “like” this newsletter by clicking the ❤️ just below, which helps me get visibility on Substack.

Until next week,

Mehdi Yacoubi