Hi there, it’s Mehdi Yacoubi, co-founder at Vital, and this is The Long Game Newsletter. To receive it in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

I took the last four weeks off of The Long Game to think, work and focus on other projects. We’re now back to regular schedule!

In this episode, we explore:

Let’s dive in!

I saw a few conversations about psychosomatic conditions on Twitter. This is a topic near and dear to my heart as I have been very prone to those types of problems for years, from chronic back pain, to knee pain, to neck pain and more.

First, this tweet by Jonny Miller:

Then, Nick Cammarata rightfully points to Sarno’s theory (that I’ve been sharing so many times on The Long Game):

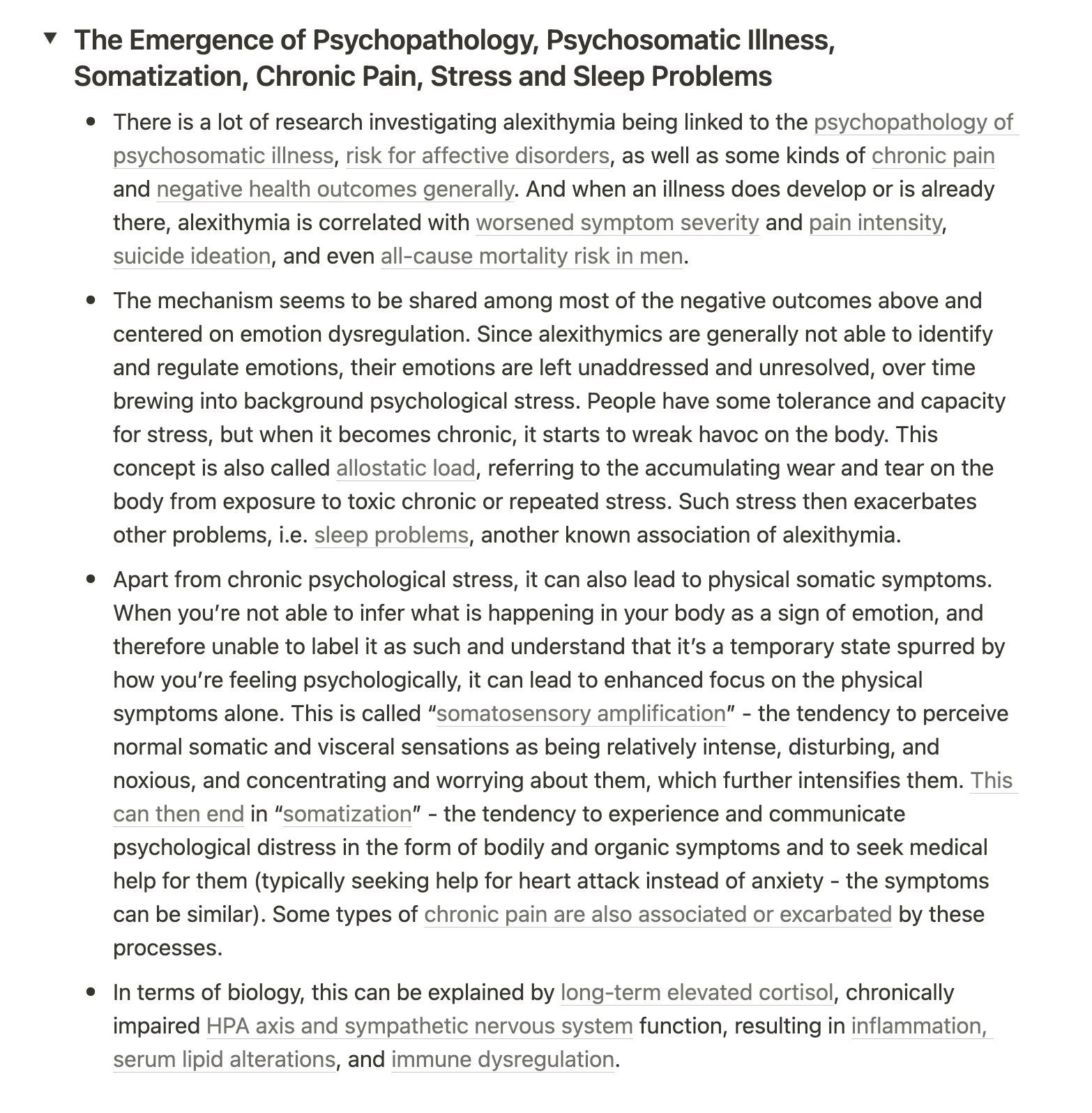

This is a good summary of how psychosomatic illnesses arise:

My impression is that even if, anecdotally, thousands of people managed to completely cure their chronic conditions through the work of Dr. Sarno, it still appears woo to the conventionally minded. I expect more research paper exploring this in the next few years.

Whether you’ll like it or hate it, this is a thought-provoking piece.

That is the most uninformative statement that people are inclined to make? My nominee would be “I love to travel.” This tells you very little about a person, because nearly everyone likes to travel; and yet people say it, because, for some reason, they pride themselves both on having travelled and on the fact that they look forward to doing so.

The opposition team is small but articulate. G. K. Chesterton wrote that “travel narrows the mind.” Ralph Waldo Emerson called travel “a fool’s paradise.” Socrates and Immanuel Kant—arguably the two greatest philosophers of all time—voted with their feet, rarely leaving their respective home towns of Athens and Königsberg. But the greatest hater of travel, ever, was the Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa, whose wonderful “Book of Disquiet” crackles with outrage:

I abhor new ways of life and unfamiliar places. . . . The idea of travelling nauseates me. . . . Ah, let those who don’t exist travel! . . . Travel is for those who cannot feel. . . . Only extreme poverty of the imagination justifies having to move around to feel.

If you are inclined to dismiss this as contrarian posturing, try shifting the object of your thought from your own travel to that of others. At home or abroad, one tends to avoid “touristy” activities. “Tourism” is what we call travelling when other people are doing it. And, although people like to talk about their travels, few of us like to listen to them. Such talk resembles academic writing and reports of dreams: forms of communication driven more by the needs of the producer than the consumer.

One common argument for travel is that it lifts us into an enlightened state, educating us about the world and connecting us to its denizens. Even Samuel Johnson, a skeptic—“What I gained by being in France was, learning to be better satisfied with my own country,” he once said—conceded that travel had a certain cachet. Advising his beloved Boswell, Johnson recommended a trip to China, for the sake of Boswell’s children: “There would be a lustre reflected upon them. . . . They would be at all times regarded as the children of a man who had gone to view the wall of China.”

Travel gets branded as an achievement: see interesting places, have interesting experiences, become interesting people. Is that what it really is?

Pair this with: Travel is no cure for the mind.

Like many of you, I watched and loved the Arnold Netflix documentary.

I thought this post by David Senra was excellent and a perfect description of Arnold’s unique mindset.

The extreme mindset of a young Arnold Schwarzenegger:

1. You are a winner, Arnold. I wrote this down and put it where I would see it. I repeated it a dozen times a day.

2. My drive was unusual, I talked differently than my friends; I was hungrier for success than anyone I knew.

3. I had this insatiable drive to get there sooner. Whereas most people were satisfied to train two or three times a week, I quickly escalated my program to six workouts a week.

4. I’d always been impressed by stories of greatness and power. Caesar, Charlemagne, Napoleon were names I knew and remembered. I wanted to do something special, to be recognized as the best.

5. I was literally addicted.

6. I didn’t care what I had to go through to get it.

7. My mind was totally locked into working out and I was annoyed if anything took me away from it.

8. My weight room was not heated, so naturally in cold weather it was freezing. I didn’t care. I trained without heat, even on days when the temperature went below zero.

9. I had a photographer take pictures at least once a month. I studied each shot with a magnifying glass.

10. I sacrificed a lot of things most bodybuilders didn’t want to give up. I just didn’t care, I wanted to win more than anything. And whatever it took to do it, I did.

11. Every day I hear someone say, “I’m too fat. I need to lose twenty-five pounds, but I can’t. I never seem to improve.” I’d hate myself if I had that kind of attitude, if I were that weak.

12. I listened only to my inner voice, my instincts.

13. People’s ideas were small. There was too much contentment, too much acceptance of things as they’d always been.

14. My own thinking was tuned in to only one thing: becoming Mr. Universe. In my own mind, I was Mr. Universe; I had this absolutely clear vision of myself up on the dais with the trophy. It was only a matter of time before the whole world would be able to see it too. And it made no difference to me how much I had to struggle to get there.

15. Once I was over the initial disappointment of losing, I began trying to understand exactly why I had lost. I tried to be honest, to analyze it fairly. I still had some serious weaknesses. For me, that was a real turning point.

16. I was relying on one thing. What I had more than anyone else was drive. I was hungrier than anybody. I wanted it so badly it hurt. I knew there could be no one else in the world who wanted this title as much as I did.

17. I had thought perhaps he had some special exercises, but that wasn’t true. He concentrated on the standard exercises. That was his “secret” —concentration.

18. I started training in an area where there were no distractions.

19. I had lists and charts of the things I needed to concentrate on pasted all over. I looked at them every day before I began working out. It became a twenty-four-hour-a-day job; I had to think about it all the time.

20. I continued doing precisely what I knew I needed to do. In my mind, there was only one possibility for me and that was to go to the top, to be the best.

21. I remember certain people trying to put negative thoughts into my mind, trying to persuade me to slow down. But I had found the thing to which I wanted to devote my total energies and there was no stopping me.

22. They weren’t mentally prepared for intensive championship training; they weren’t thinking about it. I knew the secret: Concentrate while you’re training. Do not allow other thoughts to enter your mind.

23. When I went to the gym I got rid of every alien thought in my mind.

24. I wanted to create an empire.

Austen Allred shared this article on the benefits of being unconventionally-minded as a founder. It’s worth the read.

“Many of the more successful entrepreneurs seem to be suffering from a mild form of Asperger’s where it’s like you’re missing the imitation, socialization gene,” Thiel said Tuesday at George Mason University. “We need to ask what is it about our society where those of us who do not suffer from Asperger’s are at some massive disadvantage because we will be talked out of our interesting, original, creative ideas before they’re even fully formed. Oh that’s a little bit too weird, that’s a little bit too strange and maybe I’ll just go ahead and open the restaurant that I’ve been talking about that everyone else can understand and agree with, or do something extremely safe and conventional.”

An individual with Asperger’s Syndrome — a form of autism — has limited social skills, a willingness to obsess and an interest in systems. Those diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome tend to be unemployed or underemployed at rates that far exceed the general population. Fitting into the world is difficult.

While full-blown Asperger’s Syndrome or autism hold back careers, a smaller dose of associated traits appears critical to hatching innovations that change the world.

“A typical child might just accept, ‘Okay this is just the way it’s done, this is how we do things in our culture or family,” said Simon Baron-Cohen, director of the Autism Research Center in Cambridge. “Someone with autism or Asperger’s, they kind of ask those why questions. They want more logical answers. Just saying ‘Well we do this just because everybody else does,’ that doesn’t meet their test of logic.”

Obsessiveness, another trait of those with Asperger’s, also pays off when building a tech company.

Microsoft’s co-founders Bill Gates and Paul Allen were comfortable coding software for hours on end as young programmers.

“Some of the more prudish people would say ‘Go home and take a shower.’ We were just hard-core, writing code,” as Gates told author Walter Isaacson in The Innovators.

James Dyson insists on some similar points throughout his books, although without mentioning Aspergers:

A strong will and raw doggedness, as stubborn as a mule, is the key ingredient to success. It's about not giving up, even when faced with setbacks or failures. You have to be willing to push through obstacles and keep going, no matter how challenging it may seem. That kind of persistence is what separates those who succeed from those who don't.

I started this book, it’s a data-driven guide to better, more relaxed parenting.

With Expecting Better, award-winning economist Emily Oster spotted a need in the pregnancy market for advice that gave women the information they needed to make the best decision for their own pregnancies. By digging into the data, Oster found that much of the conventional pregnancy wisdom was wrong. In Cribsheet, she now tackles an even greater challenge: decision-making in the early years of parenting.

As any new parent knows, there is an abundance of often-conflicting advice hurled at you from doctors, family, friends, and strangers on the internet. From the earliest days, parents get the message that they must make certain choices around feeding, sleep, and schedule or all will be lost. There's a rule—or three—for everything. But the benefits of these choices can be overstated, and the trade-offs can be profound. How do you make your own best decision?

Armed with the data, Oster finds that the conventional wisdom doesn't always hold up. She debunks myths around breastfeeding (not a panacea), sleep training (not so bad!), potty training (wait until they're ready or possibly bribe with M&Ms), language acquisition (early talkers aren't necessarily geniuses), and many other topics. She also shows parents how to think through freighted questions like if and how to go back to work, how to think about toddler discipline, and how to have a relationship and parent at the same time.

Ps: send me your best parenting recommendations 💌

When I read biographies, early lives leap out the most. Leonardo da Vinci was a studio apprentice to Verrocchio at 14 years old. Walt Disney took on a number of jobs, chiefly delivering papers, by 11. When Vladimir Nabokov was 16, he published his first poetry collection while still in school. Andrew Carnegie finished schooling at 12 and was 13 when he began his second job as a telegraph office boy, where he convinced his superiors to teach him the telegraph machine itself. By 16, he was the family’s mainstay of income.

Biographers and readers tend to fixate on the celebrity itself, the time when people become famous or remarkable. But before their success, even their early lives contain something revealing. Before you grasp, you have to reach. How did they learn to reach?

In my examples, the individuals were all doing from a young age as opposed to merely attending school. And while they may not have wanted to work, the work was nonetheless something that they, their families, and society felt was useful, purposeful, and appreciated. In a sense, they had useful childhoods.

Do children today have useful childhoods?

So the question we should ask is this: in worshiping diversity, in making it the highest value, what is it that we are missing? Is this an exercise in attention redirection, a kind of magic show in which you’re watching the magician and don’t notice the gorilla jumping up and down in back of the stage?

There’s a latent premise in this line of questioning. When you observe, as we did, that what’s going on is both very evil and very silly, it sounds almost self-contradictory. How can something be both very silly and very evil at the same time? The answer is that what’s going on is very silly, but the silliness is distracting us from very important things. That’s the nature of the evil. Diversity becomes a kind of divertissement, distracting our attention from the things that really matter.

What I’d like to do is delineate a few areas in which diversity is making us ignore the real issues that we should be paying attention to. I want to suggest that, at least on a public-policy level, all these debates about diversity, identity politics, multiculturalism, the woke religion, etc., should be treated like debates about homelessness. Homelessness is a mess. It’s a problem. And at the same time that it is a very real problem, it is a giant machine to redirect attention from all the other problems across America toward a narrow aspect of big-city dysfunction. When homelessness is forced into every policy conversation, it leads to circuitous, dead-end reasoning—We’re never going to fix homelessness until we fix the schools, but we’re never going to fix the schools, the police, or even the roads until we fix homelessness. It becomes an all-purpose excuse for ignoring what’s really going on. So let me, in quick succession, list a few of the deeper issues obscured by our diversity obsession today.

Pair with: Ideological Signaling Has No Role in Research

Fascinating piece on modern dating.

Elite men

Diana Fleischman writes:

Courtship is expensive and complicated by design, and it’s the limiting factor of the sexual fulfillment of men

When these transaction costs fall via fewer social sanctions, the market becomes more liquid and elite men have ~infinite choice. And because men have evolved to maximise partners at minimal cost (commitment), happy days.

There’s also an important temporal dynamic to this. It gets better for elite men and worse for women over time.

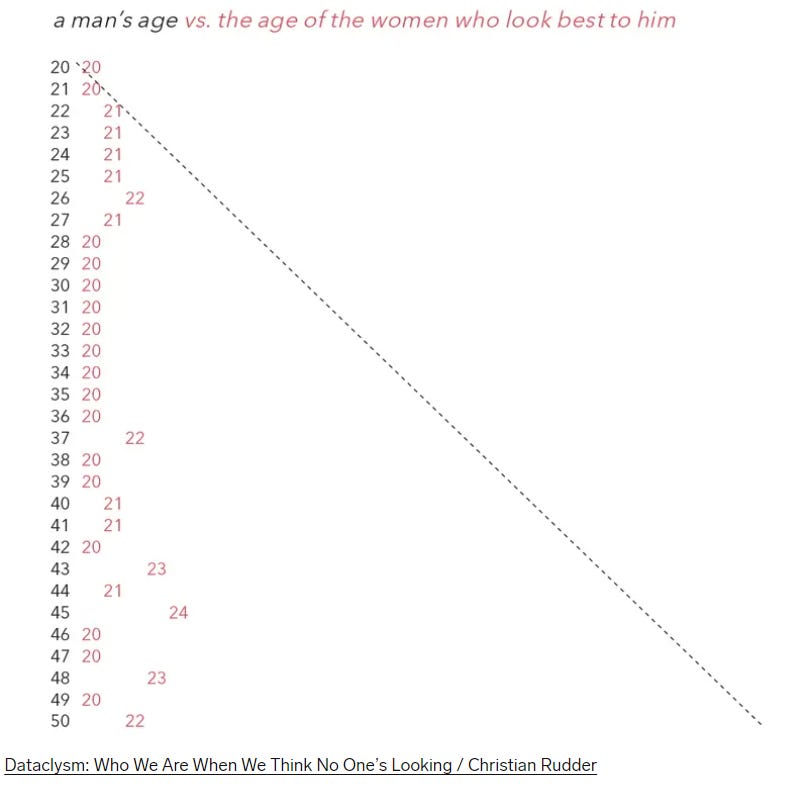

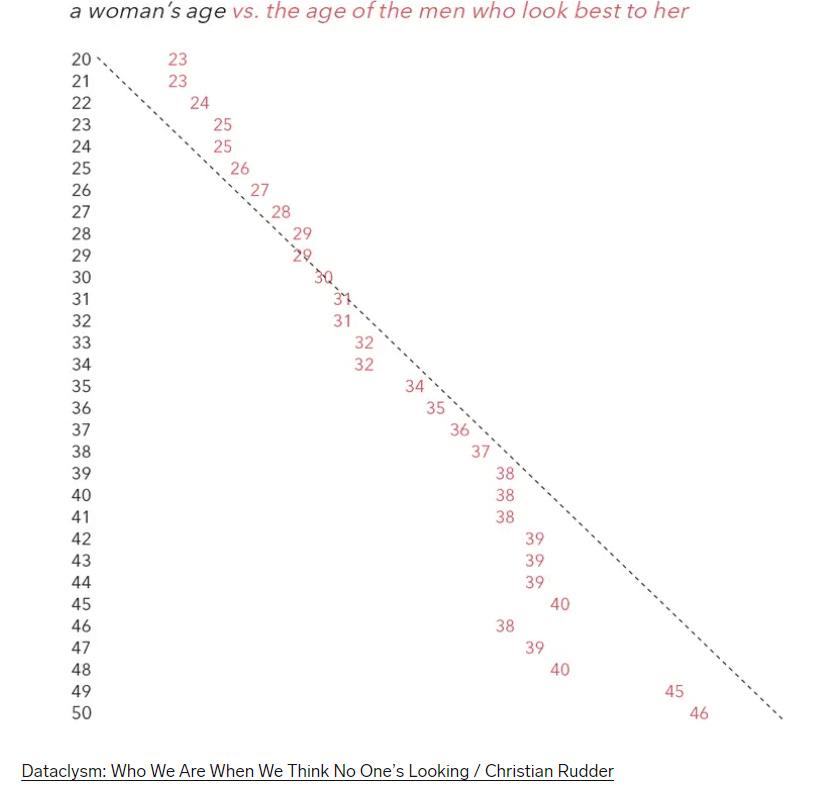

Men’s prospects generally rise over time. This is for two reasons. First, men’s age preference for women is for younger women, and optimally forever fixed at ~22.

So there are more women in their target market as they age (ie. younger women relative to them). This is reversed for women. They prefer men older than them:

So women’s target market shrinks over time. And they face rising competition over time, as they compete with younger and younger women. (There are some very nice dynamic charts for someone who can bothered making them.)

Leonardo di Caprio is the Platonic example of this. He behaves exactly as you would expect a man who could have any woman in the world to behave under this model.

This model predicts that elite men would get married and have children later as they can’t believe their luck to live into a society with the cultural sanction and technology to provide infinite liquidity and availability of women for sex. And here we are. Tinder brought these men the Uber Eats model for sex.

Of course, this itself may be a delusion. I have written before that social norms function as a way to bridge decades of blind spots:

Culture also guides you with strange long-ago-forged nudges to get you over blind spots. You don’t know you want grandkids when you’re 20. The challenge is you’ll want them in 30 — 40 years. Tell that to a 20 year old and he may have trouble hearing you over the cacophonic need to fight and f*ck. So how do you set the right behavioral cadence for that? What can bridge decades long blind spots? Cultural norms to marry and bear children. The payoff will come.

So ironically, this dynamic may not even be good for elite men over the longer run. I do not envy any of my friends without kids who “feast” in the mating market. But these are the near-term preferences that govern elite male behaviour.

Pair with: Hook Up Culture Is Bad For The Boys Too

This is an important and beautiful study.

The TL;DR:

Researchers examined MRI scans of happy couples who have been together for ~21 years and found that their reward pathways + dopamine-rich areas mirrored those of ppl who just fell in love. Meaning, you can be just as madly in love with someone decades from now.

The abstract:

The present study examined the neural correlates of long-term intense romantic love using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Ten women and 7 men married an average of 21.4 years underwent fMRI while viewing facial images of their partner. Control images included a highly familiar acquaintance; a close, long-term friend; and a low-familiar person.

Effects specific to the intensely loved, long-term partner were found in:

(i) areas of the dopamine-rich reward and basal ganglia system, such as the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and dorsal striatum, consistent with results from early-stage romantic love studies; and

(ii) several regions implicated in maternal attachment, such as the globus pallidus (GP), substantia nigra, Raphe nucleus, thalamus, insular cortex, anterior cingulate and posterior cingulate. Correlations of neural activity in regions of interest with widely used questionnaires showed: (i) VTA and caudate responses correlated with romantic love scores and inclusion of other in the self; (ii) GP responses correlated with friendship-based love scores;

(iii) hypothalamus and posterior hippocampus responses correlated with sexual frequency; and (iv) caudate, septum/fornix, posterior cingulate and posterior hippocampus responses correlated with obsession.

Overall, results suggest that for some individuals the reward-value associated with a long-term partner may be sustained, similar to new love, but also involves brain systems implicated in attachment and pair-bonding.

Very good video for my lifting friends, to avoid staying intermediate forever.

Pair with: Why Natural Lifters Need To BULK

A very interesting conversation and a new & original framing as to what it means for a culture to stop valuing having many children: auto-destruction.

Time management with a kid is something else—so I had to remind myself many times that 20 minutes of push-ups or pull-ups can be a solid workout. Maybe not as satisfying as a full gym session, but gets the job done, which is way better than nothing.

I have always believed that the hardest parts of my professional life were the moments when I faced failure, criticism, and doubt. These challenges pushed me to the limits of my creativity, determination, and resilience. They tested my belief in my ideas and forced me to constantly adapt and improve. But it was precisely in those difficult times that I discovered my true strength and the power of perseverance. Each setback became an opportunity to learn, grow, and come back stronger than before. So, embrace the hardships, for they are the stepping stones to success.

— James Dyson

Thanks for reading!

If you like The Long Game, please share it on social media or forward this email to someone who might enjoy it. You can also “like” this newsletter by clicking the ❤️ just below, which helps me get visibility on Substack.

Until next week,

Mehdi Yacoubi