Hi there, it’s Mehdi Yacoubi, co-founder at Vital, and this is The Long Game Newsletter. To receive it in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

In this episode, we explore:

Let’s dive in!

I think a lot of us intuitively see a link between good mental health and exercise, and this recent paper validated this intuition.

Abstract

Objective To estimate the efficacy of exercise on depressive symptoms compared with non-active control groups and to determine the moderating effects of exercise on depression and the presence of publication bias.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis with meta-regression.

Data sources The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, SPORTDiscus, PsycINFO, Scopus and Web of Science were searched without language restrictions from inception to 13 September2022 (PROSPERO registration no CRD42020210651).

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies Randomised controlled trials including participants aged 18 years or older with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder or those with depressive symptoms determined by validated screening measures scoring above the threshold value, investigating the effects of an exercise intervention (aerobic and/or resistance exercise) compared with a non-exercising control group.

Results Forty-one studies, comprising 2264 participants post intervention were included in the meta-analysis demonstrating large effects (standardised mean difference (SMD)=−0.946, 95% CI −1.18 to −0.71) favouring exercise interventions which corresponds to the number needed to treat (NNT)=2 (95% CI 1.68 to 2.59). Large effects were found in studies with individuals with major depressive disorder (SMD=−0.998, 95% CI −1.39 to −0.61, k=20), supervised exercise interventions (SMD=−1.026, 95% CI −1.28 to −0.77, k=40) and moderate effects when analyses were restricted to low risk of bias studies (SMD=−0.666, 95% CI −0.99 to −0.34, k=12, NNT=2.8 (95% CI 1.94 to 5.22)).

Conclusion Exercise is efficacious in treating depression and depressive symptoms and should be offered as an evidence-based treatment option focusing on supervised and group exercise with moderate intensity and aerobic exercise regimes. The small sample sizes of many trials and high heterogeneity in methods should be considered when interpreting the results.

Lastly, when trying to start/restart being physically active, it's essential to work first on consistency and developing a genuine appreciation/love for a type of physical activity. Once that's done, exercising becomes effortless, and one of the best parts of the day.

As always, there’s a lot of chatter around what is the Optimal™️ diet, what is the Optimal™️ training protocol, what is the Optimal™️ sleeping routine, etc.

I think some of those discussions are interesting, and the research around them can serve as good guidance as to what to try. The issue is when people extrapolate these findings to create blanket Optimal™️ rules for everyone.

I liked this small text on the value of N=1:

N=1 is the ultimate truth.

Large population level studies provide a decent starting point of what 'should' work assuming you're an average representation of the population. This is useful if you have no previous data on what works *for you*

If you do have previous data on what works *for you*, you would have to be some kind of idiot to ignore that & instead go with what works the best for the average population member.

E.g. assume you get a major disease that you've never had before. Science says on a population level, treatment A is superior to treatment B so you start with treatment A, but you don't respond as the average subject in the study did. Do you stick with treatment A, & go down with the ship, because "science says" it is the superior choice? Of course not, you try option B!

Your *individual* response to an intervention should always be placed above the average population member's response to an intervention.

Too few academics understand this.

I’m resharing this excellent article that I re-read recently.

The world until recently was overflowing with onramps of opportunity, even for children, and we seem to do poorly at producing new ones. Modern complexity may have erased some avenues for agency (no boy can meaningfully learn the telegraph), but I suspect how we have oriented the world, not technology, is the main problem. 13-year-old Steve Jobs called Bill Hewlett and received a summer job at HP, which would be unsurprising in Carnegie’s time, was certainly surprising for 1968, and is obviously verboten today.

We seem to have a political (public) imagination so shallow that it cannot conceive of what to even do with children, especially smart children. We fail to properly respect them all the way through adolescence, so we have engineered them to be useless in the interim. We do not need children to work, that is abundantly clear, but by ensuring there is nothing for them to do we are also sure to destroy more onramps towards making meaningful contributions to the world.

Much of the fault for this lies in an attempt at systematizing skill and knowledge transfer so thoroughly that people begin to conceive of it as the task of school, rather than a normal consequence of work. Because of this shift, childhood contains the age where one can intuit very well how the world works while being prevented from acting upon it meaningfully. Instead of an adolescence full of rites of passage, where one attempts to master something and accept responsibility, we have made it full of waiting, and doing work—for school is work—that nearly everyone knows is fake.

A small reminder for today. An idea that is hard to grasp deeply, even if you’re reminded of it many times.

It's better to think of distribution as something essential to the design of your product.

If you've invented something new but you haven't invented an effective way to sell it, you have a bad business no matter how good the product.

Superior sales and distribution by itself can create a monopoly, even with no product differentiation.

The converse is not true.

No matter how strong your product even if it easily fits into already established habits and anybody who tries it likes it immediately—you must still support it with a strong distribution plan.

— Peter Thiel

This New Technologist Manifesto is really good.

First and foremost, the new technologist is not ashamed of working in technology. They view it as a joy and a privilege. It is not defeatist nor is it with any sense of irony that we approach our work intensely.

The new technologists spend their time with each other, seeped in references and discussion, aware of histories that form an interdisciplinary school of thought and practice.

It is the goal of the new technologist to increase the “capability landscape”, thus increasing the individual’s potential for greatness. There have been people that were born and died within a time period without access to / invention of the tool they are meant for. How many Mozart’s died before the invention of the Harpsichord? Our job is to continually reduce the number of people that meet that fate, by improving the built environment.

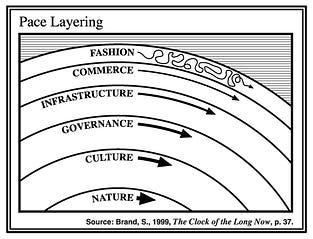

The new technologist sees hardware as part of the “nature” layer of pace layering. We want culture to be diverse and generative, and we work to produce new hardware platforms towards that diversity.

The four most important areas of next-gen / post-internet technologies are hardware, spatial, crypto, and AI. The new technologist spends their time advancing ideas, products, capital, and systems in these arenas. Why? → Because hardware and spatial represent a shift in “containers” for software, and AI and crypto represent a shift in what software is. These four areas will converge into new metas.

The new technologist does not subscribe to the cult of being a founder. Instead we seek to advance the four areas previously mentioned.

While on the surface we mostly just see large rounds and revenue or usage leaks, in reality AI companies are perhaps some of the most complex businesses we’ve had being built in tech in some time. Doing core AI model R&D necessitates a need to play 4D Chess around research communities, capital accumulation and deployment, talent acquisition, competitive understanding, and commercialization.

AI companies today find themselves in multiple cycles of R&D and commercialization, making an implicit bet that the millions or billions of dollars spent on R&D will eventually lead to market domination and massive scale years from now. This pushes these companies into a dark forest they must navigate, while stacking up R&D costs ahead of clear staying power for far longer than the vast majority of software businesses.

But to understand whether AI companies are embarking on a rollercoaster of capital deployment that is a Super Cycle, or a Euthanasia Coaster style journey, we must also understand the impending shifts that will drive all strategy over the next decade.

Who could have guessed?

In the early- to mid-1920s, the French author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry flew planes, commercially for a stint, and also for the French Air Force. He was an adventurer, a poet of life. He also wrote one of my favorite books: “Wind, Sand and Stars.” In it, I found one of the smartest lines ever written on the human condition, even though at the time he was riffing about airplanes: “Perfection is achieved not when there is nothing more to add but when there is nothing left to take away, when a body has been stripped down to its nakedness.”

That day, at the bottom of the climb, I finally understood what Saint-Exupéry was talking about. Adding comes naturally in life, from the simple act of living; habits form, mental patterns become fixed. Jealousies, insecurities and phobias take root with disturbing ease. We may try to fix ourselves, but often by slapping on more strips of duct tape.

But, against what feels like common sense, daily labor is required to return to nakedness.

A great performance is nothing more than a lovely moment, and lovely moments are everywhere. To arrive there, you need to prune away what is causing anticipation and frustration — impatience with those you love, jealousy toward a friend or anger at your children. As Saint-Exupery advises, we must take away until there is nothing left to remove. What is left when you do that? Only an action. You are in it, then, in sports or in love, with clarity, intensity and solidity. You adjust quickly and deftly. You are no longer bound by addition. You are free to act.

That’s winning. That’s perfection.

This represents a profound shift for readers, authors and publishers.

First the camera pans across eight books arrayed with hundreds of sticky tabs, flaunting that they have been closely read and meticulously annotated. Next a description runs across the screen: “Books I would sell my soul to read again for the first time”. The music crescendoes, and a manicured hand reveals the books’ covers in time with the beat, featuring authors including Simone de Beauvoir, Elena Ferrante and Sally Rooney.

The user, who is called “buryme.withmybooks”, does not say why she likes them, but that does not matter. On TikTok hyperbole is the name of the social-media game. Around 9.3m people have watched the video and almost 400,000 people have saved it for future reference.

TikTok, which has more than 1bn regular users, is making a mark on the world of publishing. Much of this is done through BookTok, the app’s community of users who comment on books. It is among the largest communities on the app; videos with this tag have been viewed 179bn times, more than twice as many as BeautyTok (beauty enthusiasts splinter into various groups). Adding #reading, #books and #literature pushes views to more than 240bn. Whoever said books are dead has not spent much time on TikTok, nor in bookstores, which now have whole displays touting titles “as seen on TikTok”.

What’s a low HRV?

At the population level, the strongest parameter associated with HRV is age. And yet, at any age, the range of HRV values is extremely large. For example, a recent study looking at almost 100 000 people, showed how rMSSD (the typical HRV feature reported by most apps and wearables) spans between 10 and 230 ms for teenagers, and still covers a range between 5 ms and 80 ms for people in their sixties. The median value for people in their 30s is about 45 ms, with a very large standard deviation (30 ms), meaning that a large percentage of people will have relatively low values at any age. Most people having concerns typically report an rMSSD of about 20 ms or a bit lower, which is quite normal if we are in our fifties, and still rather frequent even if we are younger, according to published literature in the general population.

Alright, hopefully, we have established that you are not alone and a relatively low HRV might in fact be quite normal.

Why is my HRV low?

In most cases, we simply do not know. Like most things, our HRV is partially genetically determined and partially due to our lifestyle, the environment we live in, and all sorts of other factors.

The fact that we don’t know why HRV might be lower in certain people simply highlights how there is no clear causal association between HRV and other characteristics or outcomes (in either direction).

What does a low HRV mean?

A low HRV can be normal. Research studies looking at the relationship between HRV and health outcomes show associations, not causation, between e.g. a low HRV and negative health outcomes. Even then, it might be that HRV simply reflects a condition of poor health or poor lifestyle.

Most importantly, as highlighted in the first part of this article, there is so much overlap between any two groups of people, that it is never possible to determine if a person will have a certain outcome given their HRV. When studies find that a lower HRV is related to negative outcomes, they simply find a statistical association that means very little for the individual.

For example, in the figure below, we look at a biased sample made mostly of healthy, recreational athletes. And yet, if I were to tell you that my rMSSD is 25 ms, it would be impossible to determine my age and physical activity level: there is a lot of overlap between all groups (this is data I published here).

A low HRV is associated with older age and lower physical activity levels, but it is also quite meaningless at the individual level. A lot of people that are young and active will have a low HRV, and similarly, many people will have either a low or high HRV regardless of specific health outcomes.

The absolute value of our HRV is not very informative.

Some great & thought-provoking reflections on the sexual liberation.

The sexual revolution obviously succeeded in its aim: more freedom.

The answer to the debate description (“The sexual revolution promised liberation. Fifty years on, we ask: has it delivered?”) is obviously yes.

But the reason why a debate makes sense is because many people conflate liberation (freedom) with happiness.

The revolution has unquestionably increased freedom. But it also made people less happy. Many people, though, anticipated that greater freedom would necessarily bring greater happiness.

Sadly the world doesn’t work that way.

We can’t have everything good all at once. We can have some good things, but we can’t have all good things at the same time.

Equally desirable ends often collide. Equally valued aims regularly contradict each other.

Many smart people believe that all good things can be made to conspire towards a final harmonious resolution. Freedom is good. Happiness is good. Naturally, we think (or hope) that these and all other values naturally go together. But they don’t.

The main point here is that the improvements we got from the sexual revolution also led to a deterioration in other aspects.

Louise Perry alluded to this during the debate when she quoted the economic historian Richard Henry Tawney: “Freedom for the pike is death for the minnow.”

Isaiah Berlin has likewise written that, “Both liberty and equality are among the primary goals pursued by human beings throughout many centuries; but total liberty for wolves is death to the lambs.”

If you value freedom, that’s fine. But it does have costs. Women today are freer than their grandmothers. But they are less happy.

Researchers have described this as “the paradox of declining female happiness.”

Prior to the sexual revolution, women reported higher levels of happiness than men. Broadly speaking, our grandmothers were happier than our grandfathers. Over the past several decades, though, this has reversed. Men are now happier than women. To be clear, happiness overall has declined for both men and women. Men are less happy than their grandfathers; women are less happy than their grandmothers.

But relatively speaking, men now report higher rates of happiness than women.

The sexual revolution and its accompanying effect of greater acceptance of casual sex have played a role in this.

A recent study found that after casual sex, women, on average, report high levels of loneliness, unhappiness, rejection, and regret. Conversely, men report higher satisfaction, happiness, contentment, and mood improvement.

Another study found that women are most likely to be sexually satisfied in a long-term committed relationship.

Pair with: The Case Against the Sexual Revolution

I loved these during my week in NYC. Very convenient and has great taste.

"Success is walking from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm."

— Winston S. Churchill

Thanks for reading!

If you like The Long Game, please share it on social media or forward this email to someone who might enjoy it. You can also “like” this newsletter by clicking the ❤️ just below, which helps me get visibility on Substack.

Until next week,

Mehdi Yacoubi