Writers who operate. @ Irrational Exuberance

Hi folks,

This is the weekly digest for my blog, Irrational Exuberance. Reach out with thoughts on Twitter at @lethain, or reply to this email.

Posts from this week:

-

Writers who operate.

-

Advancing the industry.

-

Notes on Enterprise Architecture as Strategy

Writers who operate.

Occasionally folks tell me that I should “write full time.” I’ve thought about this a lot, and have rejected that option because I believe that writers who operate (e.g. write concurrently with holding a non-writing industry role) are best positioned to keep writing valuable work that advances the industry. This is a lightly controversial view, so I wanted to pull together my full set of thoughts on the topic.

The themes I want to work through are:

- Evaluating believability for operators is much easier than for non-operators

- The pursuit of distribution changes what and how authors write (e.g. pulls towards topics that are trending)

- How writing full-time anchors you on writers and audiences, whereas part-time writing allows a third balancing perspective (the folks you work with in the context of your industry work)

- Invalidation events happen in industry (e.g. move from ZIRP to post-ZIRP management environment) but it’s difficult for non-operators to understand implications with conviction

- Operating is an endless source of new topics (e.g. the topics in An Engineering Executive’s Primer are the direct outcome of my operating)

- Part-time writers can still get better at writing, although maybe slower than full-time writers

I’m not particularly interested in convincing someone else whether this is the right choice for them, but hopefully at the end you’ll understand my perspective a bit.

Examples

There are many writers out there who fit into the “writers who operate” archetype. A few examples: Charity Majors, Dan Na, Eugene Yan, Hunter Walk, Tanya Reilly.

Venture capitalists use “operators” to indicate folks who’ve worked in industry as opposed to in venture, but I don’t make that nuance here–working in venture capital is “operating” in my usage. Similarly, you could try to cohort various writers by the volume of their writing, but that’s not too important to me–someone who hasn’t written anything in the past three years probably isn’t who we’re talking about, but generally this is a broad church.

Believability

Believability is a Ray Dalio and Bridgewater idea, and experiencing some public scrutiny of late (e.g. Bridgewater Had Believability Issues), but at its core the observation still rings very true: we should weigh advice more heavily from folks who we have reason to believe. Cedric Chen has a few tech-centric pieces on Believability, that are interesting reads: Believability in Practice and Verifying Believability.

First and foremost, I appreciate writers who operate because they directly experience the consequences of their choices. Cedric’s second piece tells the story of “Q”, a widely read tech leader who’s had a mixed career, as an example of needing to verify believability. I agree with that observation, but the only reason we’re able to evaluate the advice at all is because that writer is an operator. If they weren’t an operator, we wouldn’t be able to evaluate their believability at all.

Operating is, for me, remaining accountable for what I write. What I write is a pretty direct reflection of what I believe and how I operate at the time that I write it.

Distribution shapes writing

As you watch new writers come onto the “scene,” you’ll often notice a shift from a genuine passion in a given niche to engaging in topical events and controversy. The reality is that it’s exceptionally hard to write something that generates a lot of discussion, and it’s even harder to repeat that formula consistently. After folks have the experience of writing a popular piece, they often get sucked into the desire to produce more, and this ultimately means seeking wider distribution.

Reliable distribution is a hard thing to find on the internet, and one of the most obvious opportunities for distribution is to engage in controversy. Write something controversial, engaging in an existing controversy, subtweet someone who did something dumb, whatever. The problem with this is that it pulls you out of picking topics, and instead towards picking positions.

Ultimately, I don’t believe you can say anything particularly novel or interesting in reaction to a trending topic. There are certainly takes that are more or less nuanced, but mobilizing the base is not advancing the industry.

This problem is even more acute when you’re trying to make a financial living out of your writing, because matching your message to your audience becomes that much more important. You’re going to spend even more time tuning your messaging to resonate with what the audience currently believes than you are on writing something new.

Taste is tribal

A year or two back, Brie Wolfson wrote a very compelling take on taste, Notes on Taste. Reading those notes, I want nothing more than to identify as someone with taste. However, perhaps out of jealousy, I’m a bit of a taste-skeptic. I view taste principally as tribal, and find that identity-through-taste is a frequent driver of boring takes and perspectives.

As an example, think about Marc Andreessen’s recent The Techno-Optimist Manifesto. Regardless of how you personally feel about the manifesto, I’m confident that you know exactly how you’re supposed to feel about it within each of the various tribes you participate in. Further, I’m certain that you knew what you’re supposed to feel about it without even reading it. That’s not a recipe for interesting discussion.

This is particularly hard to navigate as a full-time writer, because you’ll become more focused on the tribes of other writers and the tribes of your audiences, and your standing in both is important to your success. As an operator, those tribes will matter to you, but fitting into their expectations is not essential to your success (and your survival, if this is your primary source of financial stability). There are, of course, other tribes you have to pay attention to from your operating work, but those tribes will vary across writers, such that in aggregate they allow for a broader expression.

Invalidation events

In 2020, Ranjan Roy wrote ZIRP explains the world, which is an interesting dive into how zero interest rate policy was shaping so many dimensions of the economy. Among other things, ZIRP created the conditions for hypergrowth companies and funded the industry’s shift towards larger teams driving revenue growth rather than margins. People operating in the industry today have felt this transition in layoffs, a slower hiring process, and a notable shift in the dynamic between employees and employers.

When I meet with industry peers, we spend most of our time discussing either tactical problems related to this shift (e.g. how do we benchmark costs properly to justify engineering headcount) or wondering if we should hide in a hole for several years hoping that the industry reverts to kinder time. Despite that, I see a large swath of folks pitching ZIRP-era content and strategies to struggling leaders.

The folks still making their ZIRP-era talking points aren’t bad people, but they are giving bad advice, and it’s because they’ve failed to recognize an “invalidation event.” Good advice is grounded in accurately diagnosing circumstances, and folks operating in the industry are best positioned to update their advice because they’re directly experience the industry’s changes rather than observing them from a distance.

It’s not that non-operators don’t detect these shifts, they certainly do, but it’s exceptionally challenging to quickly build confidence in a large change when operating on second hand information. Operators get a lot wrong too, but it’s my experience that self-aware operators will get direct information earlier and be in a better position to evaluate it.

Endless topics

Writing as an operator, I have a constant source of new topics. More than just any topics, these topics are the most challenging topics that engineering organizations and companies encounter. All three of my books are directly grounded in the topics I was struggling with at the time. An Elegant Puzzle focused on the challenge of managing within a hypergrowth company. Staff Engineer documented the various ways that senior engineers were finding leadership impact outside of management roles. An Engineering Executive’s Primer tracks what I’ve learned from operating in executive roles. There’s no way that I personally could have written these without the benefit of operating in those environments.

Conversely, I see folks who leave operating roles often fall into a rut of repeating topics. They want to say something, but they’re not encountering new problems, so they fall back onto their fixed experiences in the industry and come back with the same ideas.

Writing well and frequently

Occasionally folks make the assertion that it’s hard to improve as a writer if you’re only writing part-time. There’s a kernel of truth in this observation: writing up my notes on finishing my 3rd book, Primer, I described each book that I write as a separate education. Even on my third book, I’m still learning so much about how to write books. I’m not sure the ideas are getting better, but the books containing those ideas certainly are.

That being said, I’ve found that having the space to explore in my writing has created so much room for improvement that I wouldn’t have found writing under a structured publishing schedule. Free-form writing has allowed me to write when and where I have energy, and to stop writing where I don’t have much energy (e.g. I starting work on Infrastructure Engineering and then subsequently paused it). It’s also allowed me to experiment with formats and mediums: I’ve written this blog, written books, spoken at conferences, done a YouTube recording, and so on. If I was focused on very specific outcomes, I’d likely be experimenting less and trying to “exploit” the mediums more, which would focus my learning.

It’s possible I would have improved more as a writer if I did it full-time, but I’m confident that I’m not a meaningfully worse writer due to the part-time nature of my writing. I also lightly hold the belief that I’m a better writer as a result of not writing full-time. Writing on a schedule is, in my opinion, not at all fun. Further, most of my best writing is stuff that I originally think isn’t even worth writing down, which would translate poorly into a world where I need to predictably write good stuff.

Echoing my earlier comments, not trying to convince anyone to switch sides on this topic, and many non-operating writers are quite good. There are many techniques you can use to address the above topics (e.g. maintaining an active network in industry), but generally those techniques apply equally (or better) to writers who operator (e.g. writers can probably get access to any company in the industry, but you couldn’t convince me that’s not equally true for operators outside of–maybe–getting visibility into a small pool of direct competitors).

Advancing the industry.

Early in my career, I navigated most decisions by simple hill climbing: if it was a more prestigious opportunity and paid more, I took it. As I got further, and my personal obligations grew, I started to think about navigating a 40-year career, where a given job might value pace rather than prestige. Over the last few years, what I’ve come to appreciate is that there’s another phase: purpose.

Purpose isn’t intrinsically the third phase of a career, but it certainly has been for me, as I was fixated on financial stability for most of my first decade in the industry, and then by controlling my career’s pace as we had our first child. It was only after figuring out, to a certain degree, the financial and pacing pieces that I felt like I had enough room in my life to think about purpose at all.

In my “2023 year in review” post, I mentioned the idea of “advancing the industry.” Increasingly, I believe that I have a small but real platform to improve how engineering organizations operate, and that it’s worthwhile to steer my career and hobbies such that I deliberately use that platform for good. I don’t take myself too seriously here–most of what I do on any given day doesn’t advance the industry in any way–but it’s a guiding principle for me when I think about larger professional questions like, “Should I take this job?” or “What theme should I write my next book on?”

Demonstrating how this principle played into a few decent decisions:

-

Before joining Carta, I thought a long time about what kind of role gives me the most leverage to impact the industry. Some friends believe that I could impact the industry more as a full-time writer, but I personally don’t believe that. First, I believe that successful engineering organizations spread their practices widely across the industry, which makes organizational leadership extremely impactful. Second, I believe that leadership roles allow you to change individuals lives around you in ways that quietly propagate across the industry. Finally, I believe that writers who operate have a unique, powerful voice in the industry.

-

Staff Engineer and An Engineering Executive’s Primer are both books whose potential readership is relatively constrained, but that readership is also positioned to have an exceptional impact on the industry. There’s probably an alternate topic I could have written about that sold more copies (and consequently made more money), but I don’t think there are alternate topics that would have impacted the industry more

I certainly don’t apply the lens to every decision I make, but I do apply it to most long-term professional decisions, and I find it quite helpful. Even if I go against where this principle steers me, it’s worthwhile to understand why I’m going against it.

Notes on Enterprise Architecture as Strategy

Enterprise Architecture as Strategy by Jeanne W. Ross, Peter Weill, and David C Robertson is an interesting read on how integrating technology across business units shifts the company’sstrategy landscape. Written in 2006, case studies are not particularly current but the ideas remains relevant.

The technology industry is simultaneously grasped by the optimism that things are changing constantly–your skills from last year are already out of date!–and the worry that nothing particularly important has changed since the 1970s when the unix epoch began. I opened Enterprise Architecture as Strategy by Jeanne W. Ross, Peter Weill, and David C Robertson, published in 2006, with both of those ideas firmly in mind.

Despite the age, I think this is one of the better strategy books I’ve read recently. In oarticular, it has some very relevant, structured thoughts on managing coordination across business units within a given company, which is something I’ve been thinking about quite a bit as the CTO for a company with a number of sophsticated business lines.

Core concepts

The book’s core premise (summarized on pages 8-9) is that every company should build a foundation for execution composed of:

- Operating model – business process integration and standardization across business units in a company (e.g. where do you select technologies for a business unit?)

- Enterprise architecture – organizing logic for business process and IT infrastructure. Essentially, how do you service shared concerns (e.g. customer database)

- IT engagement model – the system of governance mechanisms that dictate how the business and IT work together to solve problems

This isn’t groundbreaking, but it is a useful framework. Most companies that I’ve worked within fail to set the rules for decision making, and instead allow ambiguous, semi-political systems to drive outcomes. That’s less true for companies as they grow larger, and the ongoing friction within multi-business unit companies eventually forces clearer rules, but this book suggests we could just specify the answers to these predictable problems instead of discovering them anew at each company.

These ideas are relatively less interesting in the context of a single business line company, where most of these concerns don’t show up nearly as often. (Although, any acquisition does introduce the questions, sometimes very abruptly.)

Operating models

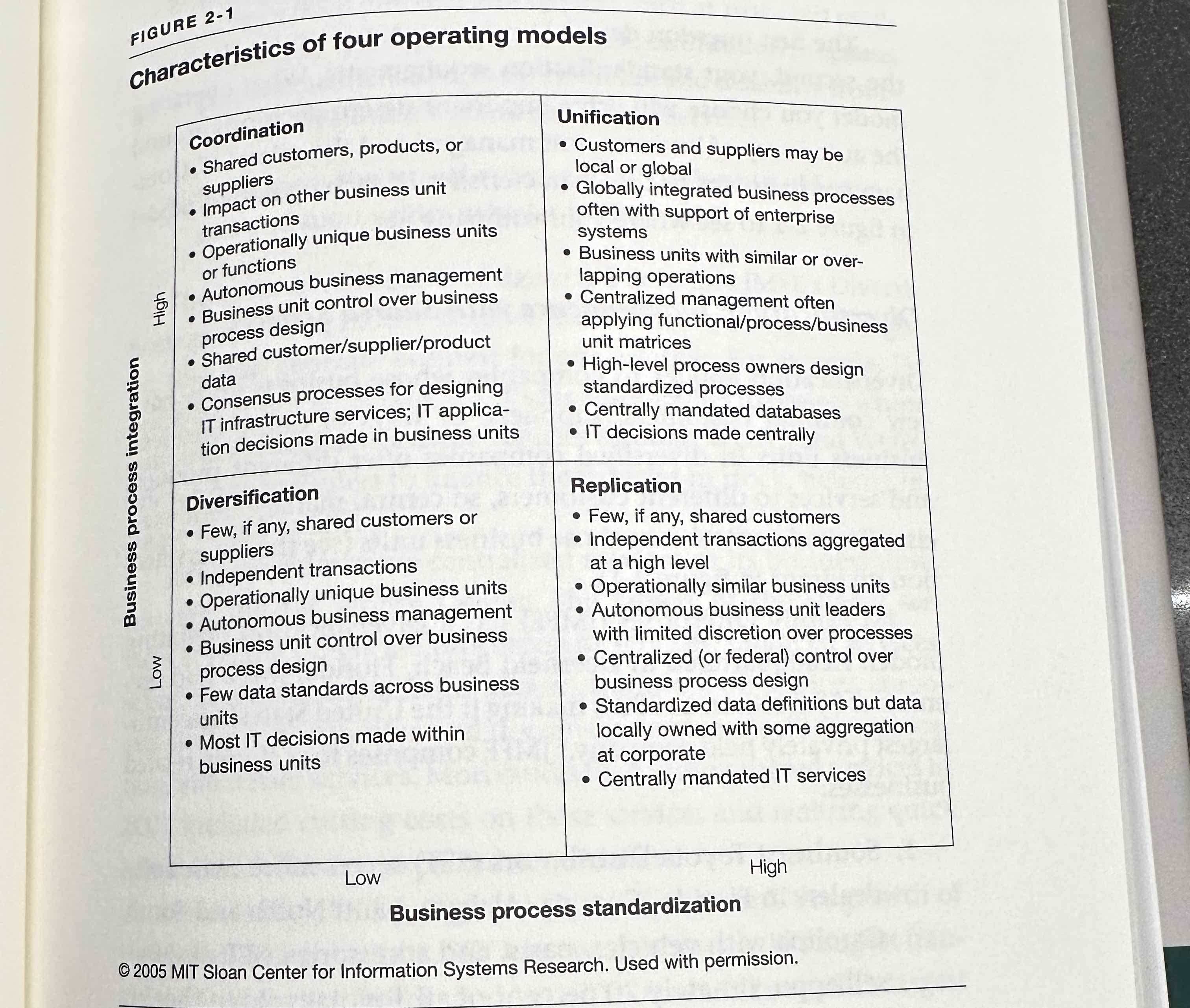

The book proposes four operating models, based on a 2 by 2 grid of two concepts: high and low standardization, and high and low integration. Standardization is running different business units in the same way. Integration is depending on the availability, accuracy and timeliness of other business units’ data.

- Coordination (low standardiation, high integration) – few shared implementations, but highly shared data

- Unification (high standardization, high integration) – shared implementation and heavy coupling of data across business units

- Diversification (low standardization, low integration) – very little alignment across business units, maybe some shared services

- Replication (high standardization, low integration) – shared implementation but little shared data across business units that serve distinct and unshared customers

I’d never seen this breakdown before reading this book, and I find it a very useful vocabulary to discuss some of the challenges I have seen across business units in a company. Specifically, it’s helpful for diagnosing why two pairs of business units behave so differently from one another. One pair has low integration, and the other has high integration, but we’ve been hoping to reason about them in the same way. The friction was obvious, but how we might modify the playbook was less obvious without this vocabulary.

I particularly appreciated this quote (p43):

A poor choice of operating model–one that is not viable in a given market–will have dire consequences. But not choosing an operating model is just as risky.

Many leadership teams are so failure-averse that they try to preserve optionality by not making decisions, but generally those decisions get made anyway, at lower levels of your organization, while you sit around and pretend that you’re studying the situation at hand.

Four stages of maturity

The book introduces (p71) four stage of enterprsie architecture maturity: business silos, standardized technology, optimized core, and business modularity. I find the stages specifically a bit hard to map into my experience, likely due to the sorts of companies I’ve worked in, but it’s an interesting lens. Further, they introduce the concept of these four stages as a progression, and their belief that it’s impossible to skip phases: you most go phase by phase from left to right.

They also introduce (p105-109) a series of practices to adopt within each phase. For example, IT ownership is decentralized in phase 2 (business silos), but should be own by a single executive in phase 3 (standardized technology).

Potentially my issue is that most startups and scaleups operate in phase 3 doing their early years, and only reach phase 4 late (if ever). That said, I’m not particularly convinced that the 4th phase is an improvement over the 3rd. More generally, I didn’t find this vocabulary particularly helpful.

Leadership agenda

This sort of book inevitably feels obligated to end with recommended steps for leaders to implement their ideas, and this book is no exception. Towards the end (p195), it proposes a set of common steps such as " Analyze your existing foundation for execution." I don’t find those super helpful, as they largely recap the previous sections of the book.

They also have a handful of principles to keep in mind while implementing these changes. The three of those principles that I find most usefula re:

- “Initiate Change From the Top” – the politics and stakeholder management to make these changes is immense. Conversely, many technical leaders–and even many engineers–want to anchor on the concept of bottoms-up leadership, that rejects making these sorts of top-down decisions. That, in my experience, simply doesn’t work beyond a couple hundred people, and we should focus more on good top-down leadership instead for larger teams. Don’t get me wrong – bottoms up leadership is extremely desirable when it works, but I think the industry spends too much time pretending we’re supporting bottoms-up leadership when infact we’re just absconding from our professional duties

- “Don’t Skip Stages” – in the maturity model (e.g. from business silos to business modularity), there’s a natural desire to simply skip to the last stage of maturity. The observation that skipping stages generally doesn’t work is an interesting one, and something I’ll need to ponder a bit

- “Implement the Foundation One Project at a Time” – the desire for transformational change often overpowers our senses, leading us to concurrent migrations that we know are very unlikely to succeed. Throttling the approach to ensure it succeeds is a recurring leadership lesson for me, and certainly resonates

Altogether, this section is worth a quick skim. It was notably less dense than the preceeding ones, but I recognize how they get edited in to make the research “more actionable.”

Case studies & surveys

This thing that impresses me the most about this book is how much data it’s built on

(page ix), relying on 50+ case studies and 200+ surveys, and operating in a field of

study the three authors focused on for a decade-plus.

Beyond simply the number of case studies, there’s the quality and level of detail in the case studies as well, which is very high. There simply aren’t enough books written this way, because they take so much effort to write, and I find it very inspiring to see the extent of research that went into the book.

Final thoughts

This was a facsinating read. Some of its biggest focuses were slightly dated by being almost 20 years old, but many of the core challenges still resonate, particularly needing an explicit operating model to navigate decisions across business units.

That's all for now! Hope to hear your thoughts on Twitter at @lethain!

|

Older messages

Create technical leverage: workflow improvements & product capabilities @ Irrational Exuberance

Wednesday, December 6, 2023

Hi folks, This is the weekly digest for my blog, Irrational Exuberance. Reach out with thoughts on Twitter at @lethain, or reply to this email. Posts from this week: - Create technical leverage:

Navigators @ Irrational Exuberance

Wednesday, November 29, 2023

Hi folks, This is the weekly digest for my blog, Irrational Exuberance. Reach out with thoughts on Twitter at @lethain, or reply to this email. Posts from this week: - Navigators - Notes on The Crux

Engineering strategy notes. @ Irrational Exuberance

Wednesday, November 22, 2023

Hi folks, This is the weekly digest for my blog, Irrational Exuberance. Reach out with thoughts on Twitter at @lethain, or reply to this email. Posts from this week: - Engineering strategy notes. -

Team Charters are a trap. @ Irrational Exuberance

Friday, November 17, 2023

Hi folks, This is the weekly digest for my blog, Irrational Exuberance. Reach out with thoughts on Twitter at @lethain, or reply to this email. Posts from this week: - Team Charters are a trap. - A bit

Thoughts on writing and publishing Primer. @ Irrational Exuberance

Wednesday, November 8, 2023

Hi folks, This is the weekly digest for my blog, Irrational Exuberance. Reach out with thoughts on Twitter at @lethain, or reply to this email. Posts from this week: - Thoughts on writing and

You Might Also Like

New Course Live: Experimentation-Led GTM

Friday, February 28, 2025

A Go-to-Market Framework That Never Fails ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

The Phone Game I Shouldn't Promote Because You'll Get Addicted

Friday, February 28, 2025

Help my spread my love of sharing by... uh, also sharing.

Chapter 3: Dynamic Societies

Friday, February 28, 2025

The third chapter from the documentary I'm creating is now live. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

🎤 The SWIPES Email (Friday, February 28th, 2025)

Friday, February 28, 2025

The SWIPES Email Friday, February 28th, 2025 An educational (and fun) email by Copywriting Course. Enjoy! Swipe: This is a handy little graphic that shows the different ways you can use the Grok

How a Medium Writer Evolved Into Bigger Business

Friday, February 28, 2025

$7 for her first article triggered this realization. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Instagram Book Promotion for Authors and Publishers

Friday, February 28, 2025

Your book on Instagram! Instagram promo image Instagram ~ a great place to advertise books

🤯 This is what calling your shot looks like…

Thursday, February 27, 2025

This year, we're playing to win. Read our annual company update right here, right now. Learn about our biggest moves yet... Playing to Win Contrarians, First, thank you. Trust is a rare currency in

3-2-1: On the secret to self-control, how to live longer, and what holds people back

Thursday, February 27, 2025

“The most wisdom per word of any newsletter on the web.” 3-2-1: On the secret to self-control, how to live longer, and what holds people back read on JAMESCLEAR.COM | FEBRUARY 27, 2025 Happy 3-2-1

10 Predictions for the 2020s: Midterm report card

Thursday, February 27, 2025

In December of 2019, which feels like quite a lifetime ago, I posted ten predictions about themes I thought would be important in the 2020s. In the immediate weeks after I wrote this post, it started

Ahrefs’ Digest #220: Hidden dangers of programmatic SEO, Anthropic’s SEO strategy, and more

Thursday, February 27, 2025

Welcome to a new edition of the Ahrefs' Digest. Here's our meme of the week: — Quick search marketing news Google Business Profile now explains why your verification fails. Google launches a